Jungle Raj: Indian Army accused of killing Van Gujjars during illegal use of firing range in Shivalik forest

Like most Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, 70-year-old Noor Mohammad has lived in forests all his life. He lived with his wife and daughter in a dera—a small cluster of huts made of mud and tree branches, usually occupied by a single Van Gujjar family—in the Chapdi range of Shivalik Forest, around 60 kilometres from Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur district. Less than 20 feet away, his son lived with his wife and their two sons. In the surrounding area, there were several more huts, of Noor’s brothers and their children. On 14 March 2018, he celebrated his daughter’s wedding in that dera. But the very next day, after six decades spent in the forest, Noor and his family were forced to leave. That morning, he recalled, bombs fired from the Indian Army’s Asan Field Firing Range, also located in the Shivalik forest, were exploding around their dera. While seeking shelter, Fatima, Noor’s 28-year-old daughter-in-law, was struck by flying shrapnel after a bomb struck a nearby tree. She died eight months pregnant.

“Fatima was resting in the sun while watching buffaloes grazing near our dera,” Noor recalled. “Me and my son were near my hut, a few hundred meters away from her. We just had finished our breakfast and were waiting for tea when we first heard the explosion.” Noor said he quickly took shelter in a nearby trench with his family and neighbours. Others in the dera ran towards a dried-out river to hide themselves from the explosion. Fatima was with Noor in the trench, when the bomb hit a tree a few hundred feet away from them. “A shell from that cannon entered in the trenches and pierced through Fatima’s abdomen,” Noor said. The firing continued for three hours, while Fatima bled to death in front of her family. The explosion killed not just Fatima and her unborn child, but also four buffaloes and a goat in the vicinity.

Fatima is survived by her husband, Samlook, and their two children, four and two years of age respectively. Over the five hours that I spoke to Noor and his family, Samlook said just one thing: “My daughter fell unconscious at the sound of the explosion, and the incident haunts her to this day.” The rest of the time, he just watched his children play, visibly depressed.

Noor’s neighbour, Gulam Nabi, who had sought shelter on the riverbed during the explosion, recounted the sequence of events that followed. “After the firing stopped, we found the daughter passed away,” Nabi said. “I immediately called 100 and informed them about the death. We waited for three hours before three police officers came.” Nabi noted that the police officials had to leave their motorcycles halfway in the jungle and walk to them. Upon reaching, the police prepared the panchnama—a site-inspection report—and asked the family what they wanted to do about it. “We told them that we don’t know the procedure, and the police should do their work,” Noor said. “The police said that the body would be taken to the city for post-mortem and explained the procedure of how daughter’s body would be cut to examine injuries. They also added that since an ambulance cannot reach here.” He added, “They implied that we would have to carry the body all the way if we wanted a post mortem.”

“We did not want anything to do with it,” Noor said. “Her body was already severely mutilated and carrying her like that to the road was not possible for us. I told the police that we don’t want a post mortem.” Noor, Samlook and the family carried Fatima’s body in a cot for about two hours in the difficult forest terrain to the area that the Van Gujjars have designated as a burial ground. The family buried Fatima the same night, at around 11pm—in the quiet of the forest, away from the police, the hospital, and any media scrutiny of the army’s actions.

Over a months-long investigation in the Shivalik forest, I found that Fatima is not the only Van Gujjar to die due to firing from the Asan Field Firing Range. Two other families said firing from the army’s Asan range killed their loved ones, both in December 2023. In fact, one local Hindi newspaper estimated that as many as 50 Van Gujjars have lost their lives between 2002 to 2023 due to such firing. The investigation revealed not just the army’s alleged killing of three civilians, but also its flagrant violation of India’s forest laws, as well as the complicity of the non-tribal locals in ensuring the silence of the Van Gujjars.

Forest ministry documents, including publicly available minutes of meetings, reveal that the Indian Army has used the Asan Field Firing Range without necessary permissions under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, and did not even hold a valid lease when Fatima was killed. We sent detailed questions to the Indian Army, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and local district, forest and police officials, but received no response from any of them at the time of publication. Despite numerous requests by the Van Gujjars seeking resettlement and repeated assurances by the Saharanpur district administration, numerous families continue to live under the threat of the firing range. The deaths of Fatima, Ghulam Mustafa and Mohammad Haneef are more than a story of grave allegations against the Indian Army; it is one of state and social apathy towards the Van Gujjar community and their rights.

*

THE VAN GUJJARS are a Muslim, semi-nomadic, pastoralist community of Gujjars (also spelled Gurjars) spread across the forests of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. In J&K and Himachal Pradesh, the community is relatively better off—they are listed among the Scheduled Tribes, and entitled to rights under India’s forest laws and positive-discrimination schemes. In Uttarakhand and UP, however, the Van Gujjars are notified among the Other Backward Castes, or OBCs, and face severe social political and economic exclusion due to their geographical location and contested claims over their forest rights. Imran Masood, the Samajwadi Party’s member of parliament from Saharanpur, too, noted that the Van Gujjars of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand should be recognised as tribals, as their counterparts in neighbouring states. “They are from the same tribe,” he said. “I will raise this in parliament in the coming sessions.”

Van Gujjars speak Gojri—a mixture of the Punjabi and Dogri languages—and their primary occupation is rearing a breed of mountain buffalo commonly known as Gojri buffaloes. As a semi-nomadic community, they migrate to the alpine forests of the upper Himalayas in summer and return to the hilly terrain of the Shivalik forest in the winter, selling milk products to towns and villages in their route. The Shivalik forest, spread over 330 square kilometres, includes Timri, Badkala, Shakumbhari and Mohand forest ranges across Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, and until the formation of Uttarakhand, it fell under the UP state administration.

After the Partition and the creation of new state boundaries, the various policing checkpoints hindered the free migration patterns of the Van Gujjars. According to Pernille Gooch, a Swedish anthropologist who has spent decades studying the Himalayan pastoralists, the new state boundaries led to “a steady decline in the space they are allowed to use.” She writes, “Politics both before and after independence created new boundaries and restrictions for pastoral movement. It has left pastoral communities like Gujjars in pockets within states with different policies, with the result that they, on their annual migration, have different sets of government officials to negotiate with, as well as different sets of regulations and rules to deal with.”

Over the years, only a few groups of Van Gujjars were able to migrate to the alpine regions in the summers through the jungles. Many Van Gujjars told me that the migration is important to them to allow the forest to heal and regrow after a season of tree lopping and grazing. “We have looked after the forest for generations,” said Gulam Rasool, one resident of the Shivalik forest. “It is our amanat”—a responsibility of guardianship. To this day, most Van Gujjars attempt the migration in the summers, albeit through different routes, often walking on roads with their cattle at night instead of going through the forest—risking the peril of harassment and violence by gau rakshaks, or Hindu-extremist vigilante groups that are known for targeting Muslims in the name of cow protection.

However, the Van Gujjars insistence on migrating to conserve the forest has worked against them, with the forest department using it to deny them protections under the Forest Rights Act. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act—more commonly known as the Forest Rights Act, or the FRA—was enacted by the Indian government in 2006. At the time, it was hailed for addressing a “historical injustice” by finally recognising the customary rights of forest dwellers, and empowering them to lay claim to their ancestral lands. The act confers a wide range of forest rights on “forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes” and “other traditional forest dwellers” who primarily reside in forest lands and depend on it for their livelihood. But in practice, the Van Gujjars of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand have been at the mercy of the states’ respective forest departments.

Since the implementation of the FRA, many Van Gujjars and civil-society groups representing them have filed claims before the forest authorities to be recognised as “other traditional forest dwelling community” recognised by the law. But both forest departments have claimed that Van Gujjars cannot be protected under the Forests Rights Act. Scholars and experts believe this is because Van Gujjars do not live in the forest permanently. Van Gujjars believe the Shivalik hills and the alpine mountains are all one and same for them. “Our presence in the jungle precedes these boundaries, these authorities and the army,” Noor said.

A 2019 study supported by the Rights and Resources Institute revealed that out of over 6,500 FRA claims filed in Uttarakhand, the state government has not issued a single individual forest right or communal forest right title. By securing community rights, the Van Gujjar deras would be granted revenue status, and as a result, come under the jurisdiction of the revenue department rather than the forest department, entitling them to civic amenities such as electricity and road infrastructure. But while the Van Gujjar pleas have been repeatedly ignored, just in 2018, the Uttar Pradesh government granted revenue status to 23 villages inhabited by members of the Tongia forest-dwelling community, including three located in the forests of Saharanpur.

A curious anthropological development offers an explanation for the denial of forest rights to the Van Gujjars. The “van”—which translates to forests—in Van Gujjar is a relatively new addition, used only for the Muslims among the pastoralist community, despite the community’s centuries-long existence in the region. As noted by Gooch and numerous other scholars, prior to the 1980s, there was no such prefix in official documents differentiating the Muslim nomadic herders from their Hindu Gujjar counterparts. Until recently, all the Gujjars in the mountainous region from northern Uttar Pradesh to Jammu were called the “Jammuwala Gujjars”—the Gujjars from Jammu, referring to their ethnic origins to the Bakarwal Gujjar tribe of Jammu. Even in the grazing permit documents from two decades ago, Van Gujjars were referred to as Jammuwala Gujjars.

Many Van Gujjars told me that they do not like the prefix added to their name. They believe it is used to differentiate them with other Gujjars from Delhi and Haryana who have political reach and resources. According to a central committee member of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan—a community youth organisation founded in 2018—who requested not to be identified, the prefix strips them of their Gujjar identity. “Now we are just jungali criminals who live in forests,” he said. “Our Muslim identity is all that matters to the bureaucracy and the political climate in this part of the country is such that nobody has the political will to be seen being favourable to us.”

It is no surprise, then, that the Van Gujjars pleas against the dangers of the Indian Army’s firing range have gone unanswered.

*

“RESPECTED SIR, we humbly request you to please consider relocating us however you deem fit to somewhere safer which allows us to live peacefully away from the jaws of bloody death.” Noor was reading from a letter he wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate in October 2019. He pulled out the letter from a crumpled grocery bag, kept in a makeshift shelf made of a shawl that hung from the roof of Noor’s hut. The grocery bag contained copies of numerous documents and applications that Noor had written to state and forest authorities. In his October letter, too, the 70-year-old reminded the district magistrate of his numerous attempts to bring urgent attention to the army firing and the threat it posed to the Van Gujjars. He described how life had become difficult for them since army arrived in the jungle.

On the margins of the letter, the village head of a nearby Shafipur village had scribbled, “sir, the applicant is a Van Gujjar from my area, and it is a very difficult time for them. I request you to please find a solution to their problems.” Noor believed that with the reference of the local elected village official, his application would finally be heard. He never heard back from the magistrate’s office. Noor has written applications to forest officers, magistrates, state legislators, parliamentarians and the chief minister since Fatima died. None responded.

Four years later, 11-year-old Mohammad Haneef was herding the family’s three buffaloes when he came across a ball-shaped metal object about the size of a football. Haneef lived on the outskirts of the Shahpur Gada village, close to the forest’s Badkala range, in a dera with his parents and three siblings. It was getting late when he found the metal object, and he picked it up and carried it home. On reaching the hut, he tied the cattle in their shed, around fifty-metres away from his home, and placed the object near a large stone bowl in the shed used to feed the cattle. Early next morning, when Haneef went out to play with his new toy, it exploded. The toy was a bomb fired from the Asan Field Firing Range that had failed to blast on impact. Haneef died on 13 December 2023, his body torn to pieces.

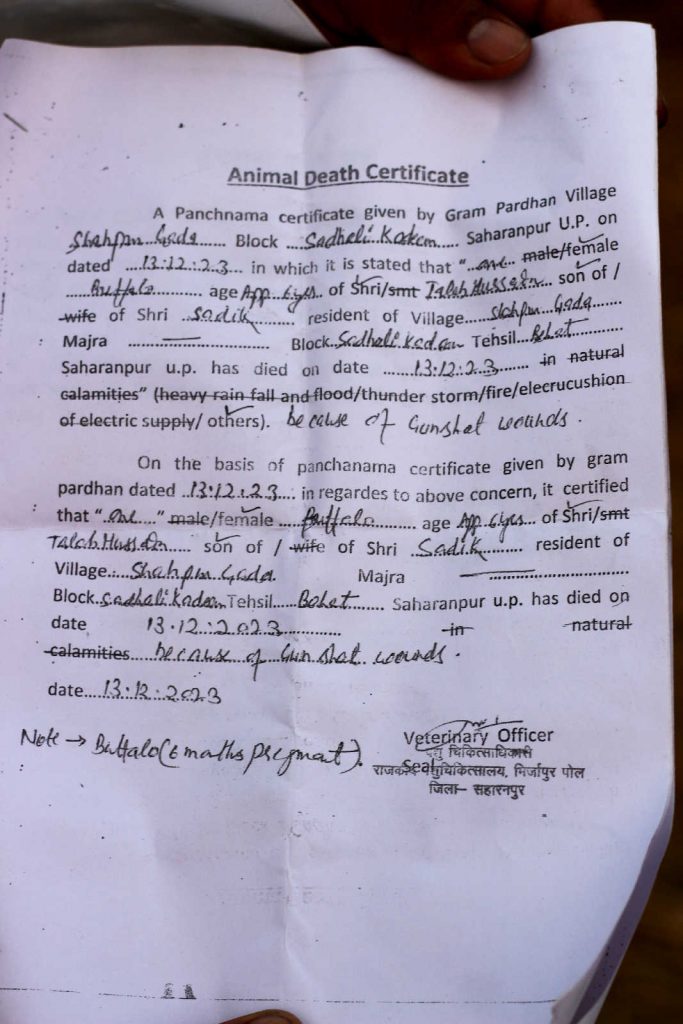

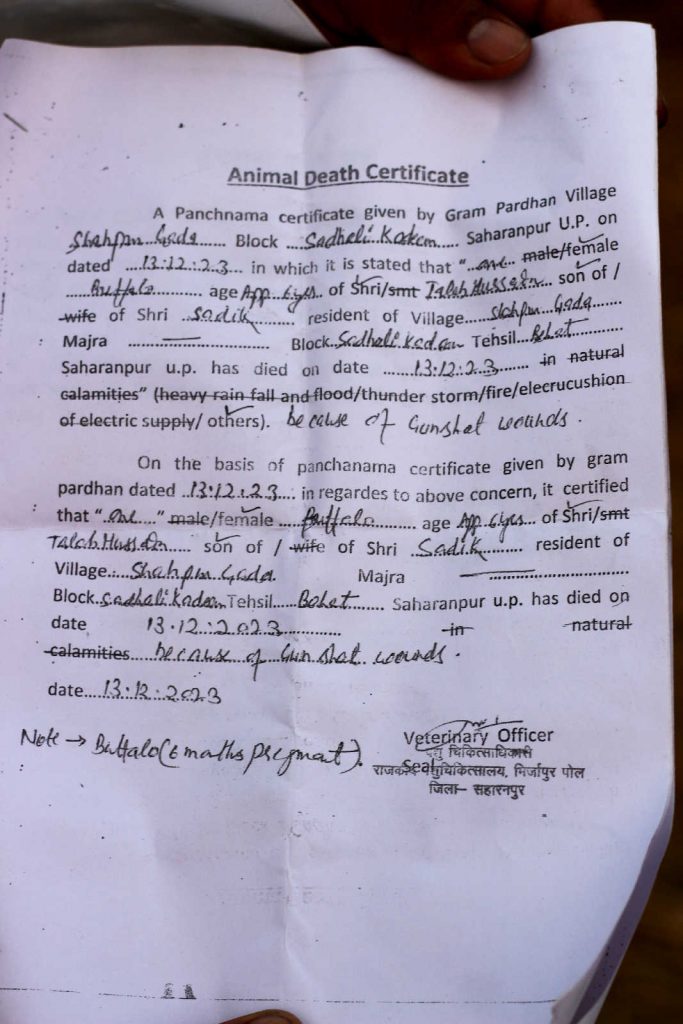

The central committee member of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan learnt these details from their representative in the area. Talib Hussain, Haneef’s father, confirmed the circumstances of his son’s death but refused to discuss it. Haneef’s post-mortem report, a copy of which is with the Polis Project, states that “Haneef died due to shock and haemorrhage as a result of antemortem blast injuries.” In the description of the antemortem injuries, it notes, “Blast injury marks present all over body,” and describes the mutilations suffered by the body. The explosion killed one of Hussain’s buffalos as well. The Animal Death Certificate, issued by district veterinary officer on 13 December, notes that the six-month pregnant buffalo died of “gunshot wounds.”

According to the central committee member, the police initially threatened to charge Talib Hussain for taking army property from the forest without permission, but subsequently withdrew the threat. “They dropped the threat because if the news came out that the army left an explosive like that in the forest, it would have created problem for them,” the member said. “They did not drop it out of sympathy for Talib because his son died.”

Two weeks later, another Van Gujjar was killed by army firing. At around 11.30am on 29 December, a shell from army firing pierced the thick, mud wall of a hut and struck Ghulam Mustafa. His entire back and hip were torn apart, his spine and organs completely crushed, and he died instantly. In his last act, the 55-year-old had used his body to shield his 11-year-old daughter, Haleema.

When I visited the family in June this year, Haleema remained in shock and unable to talk about the incident. “She has stopped talking much after the incident,” her mother, Rehnumnisa, said. Mustafa’s brother, Gulam Nabi, who shares the same name as Noor’s neighbour, was at the dera during the firing that day. “Gulam had just returned from a nikah ceremony in another dera,” Nabi said, recalling the circumstances of his brother’s death. “When the shell hit him, he died and Haleema passed out unconscious. When we found the body, we informed the army officials and the police.”

According to an entry in the Mirzapur police station’s general diary, a copy of which is available with the Polis Project, officials arrived at the scene at 04:18 pm. “The police, upon their arrival, intimidated us to bury the body and they wrote in their report that he had died upon falling from a tree,” Nabi said. Upon hearing the news, Van Gujjars living in jungles of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh reached his dera and carried Mustafa’s body to the Mirzapur police station, around 10 kilometres from his destroyed house, Nabi added.

After several hours of protest, the police finally agreed to change their report on the cause of Mustafa’s death. The inspector of the Mirzapur police station in the station’s general diary details mentioned, “Today on 29/12/23, at around 11:30 am, during army’s practice Gulam Mustafa of Badkala Khol in the Mirzapur police station area died after army’s practice items fell on him.” The police and hospital documents show that the station house officer, Rajendra Prasad wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate that day seeking permission to conduct the post-mortem at night owing to a “law and order” situation. With the DM’s permission, Mustafa’s body was sent to the Saharanpur district hospital at 4am on 30 December.

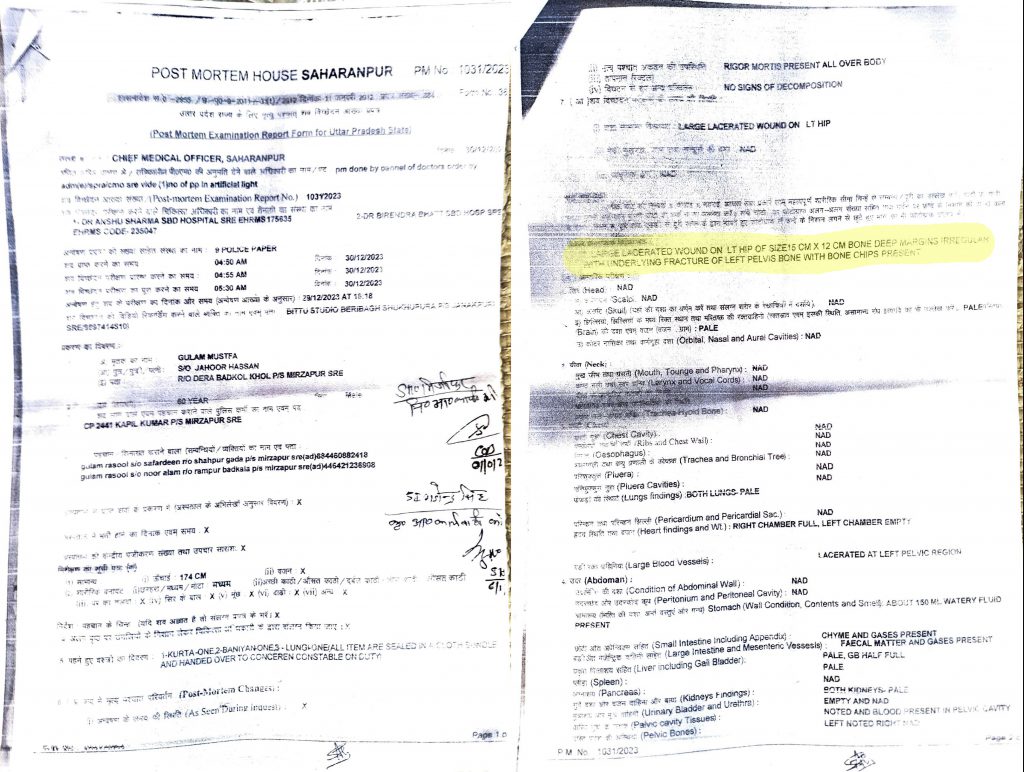

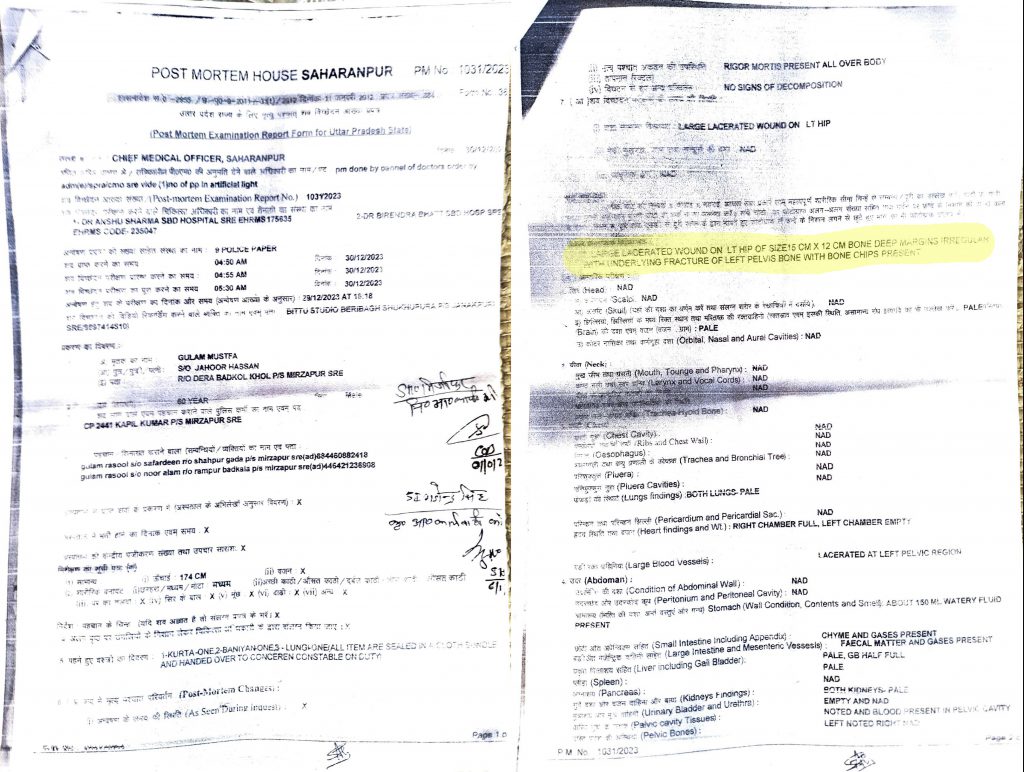

The report, similar to Haneef’s, simply stated that Mustafa “died due to shock and haemorrhage as a result of antemortem injuries.” The report described the injuries as “a large lacerated wound on hip of size 12cm*15cm bone deep margins irregular with underlying fracture of left pelvis bone with bone chips present.” A forensic expert with nearly a decade of experience conducting post mortems examined Mustafa’s report, on the condition of anonymity, and pointed to a curious omission in the document. “If the victim was hit by a shell on his back, and it didn’t exit from the other side, the shell must have been in the body,” the forensic expert said. “However, there’s no mention of the shell anywhere in the report.” Given that the police document acknowledges that Mustafa died due to the army firing, the description of the cause of death in the post-mortem is conspicuous for its absence.

Questions sent to Shweta Sain, the DFO of the Shivalik Division; Manish Bansal, the district magistrate of Saharanpur; Naresh Saini, the former member of legislative assembly from Behat; and the Indian Army, all remained unanswered at the time of publishing. The story will be updated if any is received.

*

FOR DECADES NOW, the Indian Army has been struggling to find lands to set up firing ranges. At one time, the army had 104 field firing ranges across the country—of which 12 were acquired and 92 were notified. By 2014, the number of firing ranges shrunk to 51, resulting in difficulties in training and forcing them to rely on simulations. In 2008, the Hindustan Times reported that 600 students of the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun nearly lost out on crucial battlefield training after the Uttar Pradesh government denied permission to use the firing range, until some last-minute manoeuvrings secured them access for three days. The report noted that the Asan range training was crucial to train the cadets in firing “rocket launchers and heavy-calibre mortars.”

The army officially first arrived in the Shivalik Forest in 1995. That August, the army secured the lease for 42,000 hectares of forest land under the Manoeuvres Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act, 1938, to establish the Asan Field Firing Range. The firing range is split between 25,885 hectares in Uttar Pradesh, and the rest in Uttarakhand, and caters primarily to the cadets from the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun. The army’s presence in the jungle is described in forest department documents as a matter of national security necessity.

Field firing ranges, according to military experts, are crucial in training new army personnel and making them battle ready. Van Gujjars recalled that when it was first set up, the Asan range was mostly used to train rifle firing and other manoeuvres that did not affect much of the forest, especially the Van Gujjars living there. “At first, they use to fire rifles to targets they had set 200 hundred meters aways,” Noor said. “They also used to make teams, where one would hide and the other would trace and attack them.”

Over the years, Noor and other Van Gujjars have picked up some details about the army’s training. They noted that in subsequent years, the practice sessions involved use of more dangerous artillery and explosives in the training. Most Van Gujjars I interviewed could identify various weapons, and some could recognise the different teams practicing those weapons. “There are three main explosives they use here,” Noor said. “The one that killed Fatima was the 12-kg one. It has a helicopter shaped body—with a tail, or like a rocket. When it explodes, its impact is felt in all directions.”

Documents reviewed by the Polis Project indicate that the first lease for the Asan range ended by 2005, and it was renewed by the Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand governments both for another ten years in 2007. In addition to taking permission from the two state governments, the army secured the approval of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s Forest Advisory Committee (FAC)—a central government body tasked with the evaluation of any proposal for the diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes.

By the time the renewed lease ended, the Forest Rights Act had come into force. The FRA mandated additional clearance from the state forest departments to comply with the new law, which in turn also had to obtain consent from the gram sabha—village committees—of the forest-dwelling communities before leasing forests for non-forestry purposes. But since the forest department does not consider the Van Gujjars as forest dwellers under the Forest Rights Act, the forest departments and the Forest Advisory Committee cleared the leasing of the land without a gram sabha clearance.

The Uttar Pradesh government submitted its second application for renewal of the forest lease in June 2016. When the FAC considered the proposal, on 15 June 2017, its minutes record that the Sub-Divisional Level Committee issued the necessary certificate under the act because “no right of ST/Forest Dweller on the identified land is affected and practice is being done since several years in that area.” The SDLC is the statutory body under the Forest Rights Act responsible for ensuring the functioning of gram sabhas. The FAC minutes further note that even the Divisional Forest Officer of the Shivalik Range has acknowledged in an earlier report that the forest is inhabited. The DFO submitted the report in response to the FAC’s request, which notes that even though the forest was inhabited, there was no requirement of rehabilitation or consent from the gram sabha.

The proposal received its in-principle approval on 10 April 2018, over three weeks after Fatima’s death. It would take two more years, until June 2020, for the Uttar Pradesh government to issue its final approval. Yet, the minutes from an FAC meeting for the renewal of the Uttar Pradesh forest land show that the army continued using the firing range citing “national security, war worthiness, and in anticipation of approval of the renewal of lease.” Another FAC meeting for the renewal of the Uttarakhand forest lease, held on 28 October 2021, recorded that the “use of AFFR, during the intervening period of 01.10.2017 onwards without the approval of the central government under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 amounts to violation of Forest (Conservation) Act, and accordingly, appropriate actions as per law should be initiated by the state and the IRO of the ministry.”

It is during this period of unauthorised use of the range that the alleged army firing killed Fatima. But in March 2021, the Uttar Pradesh government published the gazette notification granting a 30-year-lease for the Asan Field Firing Range, from July 2020 to June 2050.

A few months after Fatima’s death, Noor said, the army acknowledged her death and offered her family a cheque of Rs 50,000 as compensation. The Manoeuvres, Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act contains a provision for the payment of compensation for “any damage to person or property or interference with rights of privileges arising from such manoeuvres.” It is not clear why the army neither acknowledged nor offered any compensation for the deaths of Haneef and Mustafa. According to the core committee member, the explanation was simple: “This one could be easily proved that it was illegal, that’s why.” The member and Noor’s neighbour, Nabi, both also noted that Fatima’s dera was situated outside the boundaries of the firing range. “The mortars fell at least three kilometres outside than the safety zone of the firing range,” the core committee member said.

In December 2022, the member of parliament Binoy Viswam sought state-wise details of field firing ranges notified by the government and the state-wise demography as well as the number of people displaced by them. The defence ministry responded, “Notified firing ranges do not have any habitation.” But not only is this demonstrably false based on any visit to the forest, it also contradicts official records. For instance, a letter dated 15 November 1927 permits Noor’s grandfather of to graze his cattle in the forest. The document suggests that the Van Gujjars have been recorded residents in the forests for decades, even as per the terms of the Forest Rights Act. “We have lived here in the forest for generations, much before the army arrived here,” said Nabi, Noor’s neighbour.

According to Nabi, Noor’s neighbour who is also the Van Gujjar lambardar—a title used to refer to the chief of the Van Gujjars in any particular area—the Shivalik Forest region within Saharanpur district border has over 1,800 Van Gujjar families. Nabi added that these families have been claiming forest rights for years. Gooch writes that the colonial bureaucracy maintained records of Van Gujjars and their annual migration routes in these forests. These records show that since at least 1880s, the Van Gujjars have been traversing through the hilly terrains of the Shivalik Forest.

In the lease agreement, the FAC has laid down precautions the army has to take while using the forest. One of the conditions is to inform the local Divisional Forest Office prior to starting their practice, and fire a blank shot an hour before the actual commencement of the practice. At the time of Fatima’s death, an employee of the forest department named Noor Deen was also injured. Multiple witnesses confirmed that a small shrapnel from the explosion hit him on his thigh. According to media reports, Deen was in the area administering polio vaccinations for the Van Gujjar community at the time. When I asked him about the incident, he refused to talk and walked away.

The Polis Project has sent questions to Sain, the Shivalik Range DFO, inquiring whether the army informed her prior to the firing, and if so, whether she failed to alert Deen and the Van Gujjars about the same. At the time of publishing, the DFO had not sent a response.

Manoj Kumar Rai, the defence ministry official who is responsible for dealing with issues of compensation due to damage and injuries arising from the field firing range, did not respond to queries about Asan Field Firing Range or the money paid to Noor. The directorate of public relations at the defence ministry did not respond to emailed questions either. Nor did the Indian Army. The story will be updated if a response is received.

*

EVEN AS VAN GUJJARS DIE from the indiscriminate firing into the forest, the residents of the neighbouring villages near the jungle borders have not lent their support to the pastoralist community’s pleas. According to one Van Gujjar community leader who also lives in the Badshahibagh area, the reason is financial—there is money to be made in collecting and selling the scraps of the mortar shells, which are made of valuable metals such as brass and copper. The Divisional Forest Officer of Saharanpur employs external contractors through online tenders to collect mortar shells, including the unexploded ones. According the advertisement of the tender by DFO Shivalik Range, applicants can apply for collecting scraps from Badkala range and Shakambhari range for Rs 200,000 and Rs 50,000 respectively.

Ashok Chaudhury, the acting president of All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP), also spoke of the tender and the financial incentives to ignore the plight of the Van Gujjars. “The forest department has their own vested interest in keeping the army here,” Chaudhury said. “The department gets to tender out the metal scraps from the used bombs and weapons fired by the army, and get a cut from it too. It is a very lucrative business.” He continued, “Further, everybody in the vicinity gains from the army’s presence in the region. Locals get petrol and other things on cheaper rates. It is only our Van Gujjar brothers who are stuck amidst this.”

“If the firing is stopped because we are writing letters, it would affect their business,” the community leader said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “They want the army to stay even if it risks our life.” When I tried to speak to the villagers about this, they declined to speak and grew increasingly hostile.

Noor, Fatima’s father-in-law, offered more financial explanations behind the villagers’ apparent lack of concern for the Van Gujjars. He said that many villagers are involved in illegal activities within the jungle, such as cutting trees and even poaching animals. “The Van Gujjars consider the jungle our home and we do not allow that to happen in our watch,” Noor said. Recalling an incident from last year, he added, “My nephew learnt that some villagers are smuggling trees from the jungle. He directly went to the forest ranger’s office to inform about the crime. However, instead he was locked and beaten up inside the ranger’s office by forest rangers.” After that incident, Noor concluded that the forest officials are aware of, or even involved in, the illegal activities of the villagers. Other Van Gujjars listening to our conversation nodded in agreement.

Masood, the Saharanpur MP, claimed helplessness over the situation. “When I was an MLA between 2007 and 2012, I talked with all relevant authorities about it,” he said. “But since it has to be a policy decision, I cannot do much about it on my own.” However, Masood was emphatic about the illegality of the firing range. “The army shouldn’t be there,” he said. “That entire area is densely populated and is very close to the population living in the civil jurisdiction. Apart from Van Gujjars, that area has a rich ecosystem, which the army will destroy. This is a gross violation of the FRA.”

“The only reason this is happening is because the Van Gujjars are Muslims, and this government hates Muslims,” he added. “Had this been about any other community, this issue would have been dealt with more seriously. I met the commissioner several times about this when I was MLA but they only promised and did nothing.”

In recent years, villagers affiliated with Hindutva groups have also begun to target Van Gujjars because of their Muslim identity. The Van Gujjars are usually easily recognisable due to their attire. Most elders in the community wear a kurta, a kamarbandh—similar to a lungi—and a turban. Typically, Van Gujjars milk their buffaloes early in the morning and carry the milk in containers to the boundaries of the forest where vendors would buy the milk from them to sell in the cities. Following the pandemic, according to the core committee member, local groups called for a boycott of their milk accusing them of spitting in the milk and spreading corona. Previously, the Rudra Sena, a Hindu far-right organisation, has threatened violence against Van Gujjars if they remained in the forests, accusing them of “land jihad.”

One vendor, requesting anonymity, said that the Van Gujjars are a victim of dirty politics. “Every time there is a discussion of relocating the Gujjars, this issue starts to rise,” he said. “This is deliberately done to stop the relocation. If the Van Gujjars are relocated, they would be given forest lands that comes within village boundaries. Most of these lands are occupied by the politically dominant villagers.” Indeed, records of discussions between the Saharanpur DM, the DFO and other authorities show that lands discussed for possible relocation of Van Gujjars lies within nearby villages.

The question of their relocation has arisen several times in official discussions. As early as 1979, the Uttar Pradesh government published a study by Chaman Lal Bhasin, a former forest officer, discussing the need for rehabilitation of Van Gujjars from the forest. Bhasin had proposed that each Van Gujjar family be given one hectare of land for cattle rearing and 500 square meters for constructing their house, at the fringes of the jungle. But the proposal was never implemented.

In 2007, a delegation of Van Gujjars wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate requesting to limit the army to other parts of the jungle. “Since past 100 years, 20 families have been living in the Chapdi Khol area of the forest,” the letter read. The delegation never heard back from the magistrate’s office, a member of the delegation said.

The issue has persisted in recent years as well. The Saharanpur district magistrate headed a meeting on 9 October 2018, with his deputies and forest officials, to identify government land on the outskirts of the jungle to relocate the Van Gujjars who were living within the impact area of the Asan Field Firing Range. Another letter dated 4 October 2018, from the Saharanpur district magistrate to the DFO, shows that the district administration had even identified forest lands falling in village boundaries for relocating Van Gujjars. Nabi, the lambardar, said that Van Gujjars had not received any communication from the officials about this proposal. The district magistrate and the forest officer did not respond to queries about the same.

In 2019, Naresh Saini, the member of legislative assembly from Uttar Pradesh’s Behat seat, which is the closest constituency to the forests, wrote to the state secretary addressing the Saharanpur administration’s failure to rehabilitate Van Gujjars despite repeated assurances. In the letter, Saini expressed anguish on the killings of Van Gujjars inside the forest and cited a similar relocation done by the UP government in 1990 where 878 Van Gujjars were rehabilitated. “I want to bring to your notice that my constituency borders Uttarakhand where Van Gujjars in the area have been relocated in Haridwar city,” the letter read. On 19 July 2019, the state secretary forwarded the letter to the Saharanpur district magistrate, after scribbling “send urgent remarks” on the margins of the paper.

Saini pressed the issue in the legislative assembly again in 2022, a few months before he quit Congress to join the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party. He has not spoken of Van Gujjars ever since. Saini did not respond to multiple calls and messages seeking his comments.

But as Saini noted, the Van Gujjars have repeatedly requested to be relocated in light of the army firing, and the district administration has repeatedly assured them of it. There is even precedent for such relocation—in 2017, the Indian Army resettled 34 families residing in the target area of the Darranga Field Firing Range in Assam. While the Indian Army secured the lease for the Asan Field Firing Range without the consent of the Van Gujjars, Noor emphasised that the Van Gujjars would not think twice about giving the consent, if the provisions on resettlement were followed.

“Such practices are necessary for the army, how else will they win?” Noor said. “We are not saying that only we will stay in the forest and the army has to go. We only want peace in our lives. We want to be relocated to a safer place where our daughters and sons don’t die from bombs dropping from the sky. We want us to be safe, and our jungle to be safe.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the Tongias as a Scheduled Tribe community. The Polis Project regrets the error.

Related Posts

Jungle Raj: Indian Army accused of killing Van Gujjars during illegal use of firing range in Shivalik forest

Like most Van Gujjars in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, 70-year-old Noor Mohammad has lived in forests all his life. He lived with his wife and daughter in a dera—a small cluster of huts made of mud and tree branches, usually occupied by a single Van Gujjar family—in the Chapdi range of Shivalik Forest, around 60 kilometres from Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur district. Less than 20 feet away, his son lived with his wife and their two sons. In the surrounding area, there were several more huts, of Noor’s brothers and their children. On 14 March 2018, he celebrated his daughter’s wedding in that dera. But the very next day, after six decades spent in the forest, Noor and his family were forced to leave. That morning, he recalled, bombs fired from the Indian Army’s Asan Field Firing Range, also located in the Shivalik forest, were exploding around their dera. While seeking shelter, Fatima, Noor’s 28-year-old daughter-in-law, was struck by flying shrapnel after a bomb struck a nearby tree. She died eight months pregnant.

“Fatima was resting in the sun while watching buffaloes grazing near our dera,” Noor recalled. “Me and my son were near my hut, a few hundred meters away from her. We just had finished our breakfast and were waiting for tea when we first heard the explosion.” Noor said he quickly took shelter in a nearby trench with his family and neighbours. Others in the dera ran towards a dried-out river to hide themselves from the explosion. Fatima was with Noor in the trench, when the bomb hit a tree a few hundred feet away from them. “A shell from that cannon entered in the trenches and pierced through Fatima’s abdomen,” Noor said. The firing continued for three hours, while Fatima bled to death in front of her family. The explosion killed not just Fatima and her unborn child, but also four buffaloes and a goat in the vicinity.

Fatima is survived by her husband, Samlook, and their two children, four and two years of age respectively. Over the five hours that I spoke to Noor and his family, Samlook said just one thing: “My daughter fell unconscious at the sound of the explosion, and the incident haunts her to this day.” The rest of the time, he just watched his children play, visibly depressed.

Noor’s neighbour, Gulam Nabi, who had sought shelter on the riverbed during the explosion, recounted the sequence of events that followed. “After the firing stopped, we found the daughter passed away,” Nabi said. “I immediately called 100 and informed them about the death. We waited for three hours before three police officers came.” Nabi noted that the police officials had to leave their motorcycles halfway in the jungle and walk to them. Upon reaching, the police prepared the panchnama—a site-inspection report—and asked the family what they wanted to do about it. “We told them that we don’t know the procedure, and the police should do their work,” Noor said. “The police said that the body would be taken to the city for post-mortem and explained the procedure of how daughter’s body would be cut to examine injuries. They also added that since an ambulance cannot reach here.” He added, “They implied that we would have to carry the body all the way if we wanted a post mortem.”

“We did not want anything to do with it,” Noor said. “Her body was already severely mutilated and carrying her like that to the road was not possible for us. I told the police that we don’t want a post mortem.” Noor, Samlook and the family carried Fatima’s body in a cot for about two hours in the difficult forest terrain to the area that the Van Gujjars have designated as a burial ground. The family buried Fatima the same night, at around 11pm—in the quiet of the forest, away from the police, the hospital, and any media scrutiny of the army’s actions.

Over a months-long investigation in the Shivalik forest, I found that Fatima is not the only Van Gujjar to die due to firing from the Asan Field Firing Range. Two other families said firing from the army’s Asan range killed their loved ones, both in December 2023. In fact, one local Hindi newspaper estimated that as many as 50 Van Gujjars have lost their lives between 2002 to 2023 due to such firing. The investigation revealed not just the army’s alleged killing of three civilians, but also its flagrant violation of India’s forest laws, as well as the complicity of the non-tribal locals in ensuring the silence of the Van Gujjars.

Forest ministry documents, including publicly available minutes of meetings, reveal that the Indian Army has used the Asan Field Firing Range without necessary permissions under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980, and did not even hold a valid lease when Fatima was killed. We sent detailed questions to the Indian Army, the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and local district, forest and police officials, but received no response from any of them at the time of publication. Despite numerous requests by the Van Gujjars seeking resettlement and repeated assurances by the Saharanpur district administration, numerous families continue to live under the threat of the firing range. The deaths of Fatima, Ghulam Mustafa and Mohammad Haneef are more than a story of grave allegations against the Indian Army; it is one of state and social apathy towards the Van Gujjar community and their rights.

*

THE VAN GUJJARS are a Muslim, semi-nomadic, pastoralist community of Gujjars (also spelled Gurjars) spread across the forests of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir. In J&K and Himachal Pradesh, the community is relatively better off—they are listed among the Scheduled Tribes, and entitled to rights under India’s forest laws and positive-discrimination schemes. In Uttarakhand and UP, however, the Van Gujjars are notified among the Other Backward Castes, or OBCs, and face severe social political and economic exclusion due to their geographical location and contested claims over their forest rights. Imran Masood, the Samajwadi Party’s member of parliament from Saharanpur, too, noted that the Van Gujjars of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand should be recognised as tribals, as their counterparts in neighbouring states. “They are from the same tribe,” he said. “I will raise this in parliament in the coming sessions.”

Van Gujjars speak Gojri—a mixture of the Punjabi and Dogri languages—and their primary occupation is rearing a breed of mountain buffalo commonly known as Gojri buffaloes. As a semi-nomadic community, they migrate to the alpine forests of the upper Himalayas in summer and return to the hilly terrain of the Shivalik forest in the winter, selling milk products to towns and villages in their route. The Shivalik forest, spread over 330 square kilometres, includes Timri, Badkala, Shakumbhari and Mohand forest ranges across Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, and until the formation of Uttarakhand, it fell under the UP state administration.

After the Partition and the creation of new state boundaries, the various policing checkpoints hindered the free migration patterns of the Van Gujjars. According to Pernille Gooch, a Swedish anthropologist who has spent decades studying the Himalayan pastoralists, the new state boundaries led to “a steady decline in the space they are allowed to use.” She writes, “Politics both before and after independence created new boundaries and restrictions for pastoral movement. It has left pastoral communities like Gujjars in pockets within states with different policies, with the result that they, on their annual migration, have different sets of government officials to negotiate with, as well as different sets of regulations and rules to deal with.”

Over the years, only a few groups of Van Gujjars were able to migrate to the alpine regions in the summers through the jungles. Many Van Gujjars told me that the migration is important to them to allow the forest to heal and regrow after a season of tree lopping and grazing. “We have looked after the forest for generations,” said Gulam Rasool, one resident of the Shivalik forest. “It is our amanat”—a responsibility of guardianship. To this day, most Van Gujjars attempt the migration in the summers, albeit through different routes, often walking on roads with their cattle at night instead of going through the forest—risking the peril of harassment and violence by gau rakshaks, or Hindu-extremist vigilante groups that are known for targeting Muslims in the name of cow protection.

However, the Van Gujjars insistence on migrating to conserve the forest has worked against them, with the forest department using it to deny them protections under the Forest Rights Act. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act—more commonly known as the Forest Rights Act, or the FRA—was enacted by the Indian government in 2006. At the time, it was hailed for addressing a “historical injustice” by finally recognising the customary rights of forest dwellers, and empowering them to lay claim to their ancestral lands. The act confers a wide range of forest rights on “forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes” and “other traditional forest dwellers” who primarily reside in forest lands and depend on it for their livelihood. But in practice, the Van Gujjars of Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand have been at the mercy of the states’ respective forest departments.

Since the implementation of the FRA, many Van Gujjars and civil-society groups representing them have filed claims before the forest authorities to be recognised as “other traditional forest dwelling community” recognised by the law. But both forest departments have claimed that Van Gujjars cannot be protected under the Forests Rights Act. Scholars and experts believe this is because Van Gujjars do not live in the forest permanently. Van Gujjars believe the Shivalik hills and the alpine mountains are all one and same for them. “Our presence in the jungle precedes these boundaries, these authorities and the army,” Noor said.

A 2019 study supported by the Rights and Resources Institute revealed that out of over 6,500 FRA claims filed in Uttarakhand, the state government has not issued a single individual forest right or communal forest right title. By securing community rights, the Van Gujjar deras would be granted revenue status, and as a result, come under the jurisdiction of the revenue department rather than the forest department, entitling them to civic amenities such as electricity and road infrastructure. But while the Van Gujjar pleas have been repeatedly ignored, just in 2018, the Uttar Pradesh government granted revenue status to 23 villages inhabited by members of the Tongia forest-dwelling community, including three located in the forests of Saharanpur.

A curious anthropological development offers an explanation for the denial of forest rights to the Van Gujjars. The “van”—which translates to forests—in Van Gujjar is a relatively new addition, used only for the Muslims among the pastoralist community, despite the community’s centuries-long existence in the region. As noted by Gooch and numerous other scholars, prior to the 1980s, there was no such prefix in official documents differentiating the Muslim nomadic herders from their Hindu Gujjar counterparts. Until recently, all the Gujjars in the mountainous region from northern Uttar Pradesh to Jammu were called the “Jammuwala Gujjars”—the Gujjars from Jammu, referring to their ethnic origins to the Bakarwal Gujjar tribe of Jammu. Even in the grazing permit documents from two decades ago, Van Gujjars were referred to as Jammuwala Gujjars.

Many Van Gujjars told me that they do not like the prefix added to their name. They believe it is used to differentiate them with other Gujjars from Delhi and Haryana who have political reach and resources. According to a central committee member of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan—a community youth organisation founded in 2018—who requested not to be identified, the prefix strips them of their Gujjar identity. “Now we are just jungali criminals who live in forests,” he said. “Our Muslim identity is all that matters to the bureaucracy and the political climate in this part of the country is such that nobody has the political will to be seen being favourable to us.”

It is no surprise, then, that the Van Gujjars pleas against the dangers of the Indian Army’s firing range have gone unanswered.

*

“RESPECTED SIR, we humbly request you to please consider relocating us however you deem fit to somewhere safer which allows us to live peacefully away from the jaws of bloody death.” Noor was reading from a letter he wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate in October 2019. He pulled out the letter from a crumpled grocery bag, kept in a makeshift shelf made of a shawl that hung from the roof of Noor’s hut. The grocery bag contained copies of numerous documents and applications that Noor had written to state and forest authorities. In his October letter, too, the 70-year-old reminded the district magistrate of his numerous attempts to bring urgent attention to the army firing and the threat it posed to the Van Gujjars. He described how life had become difficult for them since army arrived in the jungle.

On the margins of the letter, the village head of a nearby Shafipur village had scribbled, “sir, the applicant is a Van Gujjar from my area, and it is a very difficult time for them. I request you to please find a solution to their problems.” Noor believed that with the reference of the local elected village official, his application would finally be heard. He never heard back from the magistrate’s office. Noor has written applications to forest officers, magistrates, state legislators, parliamentarians and the chief minister since Fatima died. None responded.

Four years later, 11-year-old Mohammad Haneef was herding the family’s three buffaloes when he came across a ball-shaped metal object about the size of a football. Haneef lived on the outskirts of the Shahpur Gada village, close to the forest’s Badkala range, in a dera with his parents and three siblings. It was getting late when he found the metal object, and he picked it up and carried it home. On reaching the hut, he tied the cattle in their shed, around fifty-metres away from his home, and placed the object near a large stone bowl in the shed used to feed the cattle. Early next morning, when Haneef went out to play with his new toy, it exploded. The toy was a bomb fired from the Asan Field Firing Range that had failed to blast on impact. Haneef died on 13 December 2023, his body torn to pieces.

The central committee member of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan learnt these details from their representative in the area. Talib Hussain, Haneef’s father, confirmed the circumstances of his son’s death but refused to discuss it. Haneef’s post-mortem report, a copy of which is with the Polis Project, states that “Haneef died due to shock and haemorrhage as a result of antemortem blast injuries.” In the description of the antemortem injuries, it notes, “Blast injury marks present all over body,” and describes the mutilations suffered by the body. The explosion killed one of Hussain’s buffalos as well. The Animal Death Certificate, issued by district veterinary officer on 13 December, notes that the six-month pregnant buffalo died of “gunshot wounds.”

According to the central committee member, the police initially threatened to charge Talib Hussain for taking army property from the forest without permission, but subsequently withdrew the threat. “They dropped the threat because if the news came out that the army left an explosive like that in the forest, it would have created problem for them,” the member said. “They did not drop it out of sympathy for Talib because his son died.”

Two weeks later, another Van Gujjar was killed by army firing. At around 11.30am on 29 December, a shell from army firing pierced the thick, mud wall of a hut and struck Ghulam Mustafa. His entire back and hip were torn apart, his spine and organs completely crushed, and he died instantly. In his last act, the 55-year-old had used his body to shield his 11-year-old daughter, Haleema.

When I visited the family in June this year, Haleema remained in shock and unable to talk about the incident. “She has stopped talking much after the incident,” her mother, Rehnumnisa, said. Mustafa’s brother, Gulam Nabi, who shares the same name as Noor’s neighbour, was at the dera during the firing that day. “Gulam had just returned from a nikah ceremony in another dera,” Nabi said, recalling the circumstances of his brother’s death. “When the shell hit him, he died and Haleema passed out unconscious. When we found the body, we informed the army officials and the police.”

According to an entry in the Mirzapur police station’s general diary, a copy of which is available with the Polis Project, officials arrived at the scene at 04:18 pm. “The police, upon their arrival, intimidated us to bury the body and they wrote in their report that he had died upon falling from a tree,” Nabi said. Upon hearing the news, Van Gujjars living in jungles of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh reached his dera and carried Mustafa’s body to the Mirzapur police station, around 10 kilometres from his destroyed house, Nabi added.

After several hours of protest, the police finally agreed to change their report on the cause of Mustafa’s death. The inspector of the Mirzapur police station in the station’s general diary details mentioned, “Today on 29/12/23, at around 11:30 am, during army’s practice Gulam Mustafa of Badkala Khol in the Mirzapur police station area died after army’s practice items fell on him.” The police and hospital documents show that the station house officer, Rajendra Prasad wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate that day seeking permission to conduct the post-mortem at night owing to a “law and order” situation. With the DM’s permission, Mustafa’s body was sent to the Saharanpur district hospital at 4am on 30 December.

The report, similar to Haneef’s, simply stated that Mustafa “died due to shock and haemorrhage as a result of antemortem injuries.” The report described the injuries as “a large lacerated wound on hip of size 12cm*15cm bone deep margins irregular with underlying fracture of left pelvis bone with bone chips present.” A forensic expert with nearly a decade of experience conducting post mortems examined Mustafa’s report, on the condition of anonymity, and pointed to a curious omission in the document. “If the victim was hit by a shell on his back, and it didn’t exit from the other side, the shell must have been in the body,” the forensic expert said. “However, there’s no mention of the shell anywhere in the report.” Given that the police document acknowledges that Mustafa died due to the army firing, the description of the cause of death in the post-mortem is conspicuous for its absence.

Questions sent to Shweta Sain, the DFO of the Shivalik Division; Manish Bansal, the district magistrate of Saharanpur; Naresh Saini, the former member of legislative assembly from Behat; and the Indian Army, all remained unanswered at the time of publishing. The story will be updated if any is received.

*

FOR DECADES NOW, the Indian Army has been struggling to find lands to set up firing ranges. At one time, the army had 104 field firing ranges across the country—of which 12 were acquired and 92 were notified. By 2014, the number of firing ranges shrunk to 51, resulting in difficulties in training and forcing them to rely on simulations. In 2008, the Hindustan Times reported that 600 students of the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun nearly lost out on crucial battlefield training after the Uttar Pradesh government denied permission to use the firing range, until some last-minute manoeuvrings secured them access for three days. The report noted that the Asan range training was crucial to train the cadets in firing “rocket launchers and heavy-calibre mortars.”

The army officially first arrived in the Shivalik Forest in 1995. That August, the army secured the lease for 42,000 hectares of forest land under the Manoeuvres Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act, 1938, to establish the Asan Field Firing Range. The firing range is split between 25,885 hectares in Uttar Pradesh, and the rest in Uttarakhand, and caters primarily to the cadets from the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun. The army’s presence in the jungle is described in forest department documents as a matter of national security necessity.

Field firing ranges, according to military experts, are crucial in training new army personnel and making them battle ready. Van Gujjars recalled that when it was first set up, the Asan range was mostly used to train rifle firing and other manoeuvres that did not affect much of the forest, especially the Van Gujjars living there. “At first, they use to fire rifles to targets they had set 200 hundred meters aways,” Noor said. “They also used to make teams, where one would hide and the other would trace and attack them.”

Over the years, Noor and other Van Gujjars have picked up some details about the army’s training. They noted that in subsequent years, the practice sessions involved use of more dangerous artillery and explosives in the training. Most Van Gujjars I interviewed could identify various weapons, and some could recognise the different teams practicing those weapons. “There are three main explosives they use here,” Noor said. “The one that killed Fatima was the 12-kg one. It has a helicopter shaped body—with a tail, or like a rocket. When it explodes, its impact is felt in all directions.”

Documents reviewed by the Polis Project indicate that the first lease for the Asan range ended by 2005, and it was renewed by the Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand governments both for another ten years in 2007. In addition to taking permission from the two state governments, the army secured the approval of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s Forest Advisory Committee (FAC)—a central government body tasked with the evaluation of any proposal for the diversion of forest land for non-forest purposes.

By the time the renewed lease ended, the Forest Rights Act had come into force. The FRA mandated additional clearance from the state forest departments to comply with the new law, which in turn also had to obtain consent from the gram sabha—village committees—of the forest-dwelling communities before leasing forests for non-forestry purposes. But since the forest department does not consider the Van Gujjars as forest dwellers under the Forest Rights Act, the forest departments and the Forest Advisory Committee cleared the leasing of the land without a gram sabha clearance.

The Uttar Pradesh government submitted its second application for renewal of the forest lease in June 2016. When the FAC considered the proposal, on 15 June 2017, its minutes record that the Sub-Divisional Level Committee issued the necessary certificate under the act because “no right of ST/Forest Dweller on the identified land is affected and practice is being done since several years in that area.” The SDLC is the statutory body under the Forest Rights Act responsible for ensuring the functioning of gram sabhas. The FAC minutes further note that even the Divisional Forest Officer of the Shivalik Range has acknowledged in an earlier report that the forest is inhabited. The DFO submitted the report in response to the FAC’s request, which notes that even though the forest was inhabited, there was no requirement of rehabilitation or consent from the gram sabha.

The proposal received its in-principle approval on 10 April 2018, over three weeks after Fatima’s death. It would take two more years, until June 2020, for the Uttar Pradesh government to issue its final approval. Yet, the minutes from an FAC meeting for the renewal of the Uttar Pradesh forest land show that the army continued using the firing range citing “national security, war worthiness, and in anticipation of approval of the renewal of lease.” Another FAC meeting for the renewal of the Uttarakhand forest lease, held on 28 October 2021, recorded that the “use of AFFR, during the intervening period of 01.10.2017 onwards without the approval of the central government under the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 amounts to violation of Forest (Conservation) Act, and accordingly, appropriate actions as per law should be initiated by the state and the IRO of the ministry.”

It is during this period of unauthorised use of the range that the alleged army firing killed Fatima. But in March 2021, the Uttar Pradesh government published the gazette notification granting a 30-year-lease for the Asan Field Firing Range, from July 2020 to June 2050.

A few months after Fatima’s death, Noor said, the army acknowledged her death and offered her family a cheque of Rs 50,000 as compensation. The Manoeuvres, Field Firing and Artillery Practice Act contains a provision for the payment of compensation for “any damage to person or property or interference with rights of privileges arising from such manoeuvres.” It is not clear why the army neither acknowledged nor offered any compensation for the deaths of Haneef and Mustafa. According to the core committee member, the explanation was simple: “This one could be easily proved that it was illegal, that’s why.” The member and Noor’s neighbour, Nabi, both also noted that Fatima’s dera was situated outside the boundaries of the firing range. “The mortars fell at least three kilometres outside than the safety zone of the firing range,” the core committee member said.

In December 2022, the member of parliament Binoy Viswam sought state-wise details of field firing ranges notified by the government and the state-wise demography as well as the number of people displaced by them. The defence ministry responded, “Notified firing ranges do not have any habitation.” But not only is this demonstrably false based on any visit to the forest, it also contradicts official records. For instance, a letter dated 15 November 1927 permits Noor’s grandfather of to graze his cattle in the forest. The document suggests that the Van Gujjars have been recorded residents in the forests for decades, even as per the terms of the Forest Rights Act. “We have lived here in the forest for generations, much before the army arrived here,” said Nabi, Noor’s neighbour.

According to Nabi, Noor’s neighbour who is also the Van Gujjar lambardar—a title used to refer to the chief of the Van Gujjars in any particular area—the Shivalik Forest region within Saharanpur district border has over 1,800 Van Gujjar families. Nabi added that these families have been claiming forest rights for years. Gooch writes that the colonial bureaucracy maintained records of Van Gujjars and their annual migration routes in these forests. These records show that since at least 1880s, the Van Gujjars have been traversing through the hilly terrains of the Shivalik Forest.

In the lease agreement, the FAC has laid down precautions the army has to take while using the forest. One of the conditions is to inform the local Divisional Forest Office prior to starting their practice, and fire a blank shot an hour before the actual commencement of the practice. At the time of Fatima’s death, an employee of the forest department named Noor Deen was also injured. Multiple witnesses confirmed that a small shrapnel from the explosion hit him on his thigh. According to media reports, Deen was in the area administering polio vaccinations for the Van Gujjar community at the time. When I asked him about the incident, he refused to talk and walked away.

The Polis Project has sent questions to Sain, the Shivalik Range DFO, inquiring whether the army informed her prior to the firing, and if so, whether she failed to alert Deen and the Van Gujjars about the same. At the time of publishing, the DFO had not sent a response.

Manoj Kumar Rai, the defence ministry official who is responsible for dealing with issues of compensation due to damage and injuries arising from the field firing range, did not respond to queries about Asan Field Firing Range or the money paid to Noor. The directorate of public relations at the defence ministry did not respond to emailed questions either. Nor did the Indian Army. The story will be updated if a response is received.

*

EVEN AS VAN GUJJARS DIE from the indiscriminate firing into the forest, the residents of the neighbouring villages near the jungle borders have not lent their support to the pastoralist community’s pleas. According to one Van Gujjar community leader who also lives in the Badshahibagh area, the reason is financial—there is money to be made in collecting and selling the scraps of the mortar shells, which are made of valuable metals such as brass and copper. The Divisional Forest Officer of Saharanpur employs external contractors through online tenders to collect mortar shells, including the unexploded ones. According the advertisement of the tender by DFO Shivalik Range, applicants can apply for collecting scraps from Badkala range and Shakambhari range for Rs 200,000 and Rs 50,000 respectively.

Ashok Chaudhury, the acting president of All India Union of Forest Working People (AIUFWP), also spoke of the tender and the financial incentives to ignore the plight of the Van Gujjars. “The forest department has their own vested interest in keeping the army here,” Chaudhury said. “The department gets to tender out the metal scraps from the used bombs and weapons fired by the army, and get a cut from it too. It is a very lucrative business.” He continued, “Further, everybody in the vicinity gains from the army’s presence in the region. Locals get petrol and other things on cheaper rates. It is only our Van Gujjar brothers who are stuck amidst this.”

“If the firing is stopped because we are writing letters, it would affect their business,” the community leader said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “They want the army to stay even if it risks our life.” When I tried to speak to the villagers about this, they declined to speak and grew increasingly hostile.

Noor, Fatima’s father-in-law, offered more financial explanations behind the villagers’ apparent lack of concern for the Van Gujjars. He said that many villagers are involved in illegal activities within the jungle, such as cutting trees and even poaching animals. “The Van Gujjars consider the jungle our home and we do not allow that to happen in our watch,” Noor said. Recalling an incident from last year, he added, “My nephew learnt that some villagers are smuggling trees from the jungle. He directly went to the forest ranger’s office to inform about the crime. However, instead he was locked and beaten up inside the ranger’s office by forest rangers.” After that incident, Noor concluded that the forest officials are aware of, or even involved in, the illegal activities of the villagers. Other Van Gujjars listening to our conversation nodded in agreement.

Masood, the Saharanpur MP, claimed helplessness over the situation. “When I was an MLA between 2007 and 2012, I talked with all relevant authorities about it,” he said. “But since it has to be a policy decision, I cannot do much about it on my own.” However, Masood was emphatic about the illegality of the firing range. “The army shouldn’t be there,” he said. “That entire area is densely populated and is very close to the population living in the civil jurisdiction. Apart from Van Gujjars, that area has a rich ecosystem, which the army will destroy. This is a gross violation of the FRA.”

“The only reason this is happening is because the Van Gujjars are Muslims, and this government hates Muslims,” he added. “Had this been about any other community, this issue would have been dealt with more seriously. I met the commissioner several times about this when I was MLA but they only promised and did nothing.”

In recent years, villagers affiliated with Hindutva groups have also begun to target Van Gujjars because of their Muslim identity. The Van Gujjars are usually easily recognisable due to their attire. Most elders in the community wear a kurta, a kamarbandh—similar to a lungi—and a turban. Typically, Van Gujjars milk their buffaloes early in the morning and carry the milk in containers to the boundaries of the forest where vendors would buy the milk from them to sell in the cities. Following the pandemic, according to the core committee member, local groups called for a boycott of their milk accusing them of spitting in the milk and spreading corona. Previously, the Rudra Sena, a Hindu far-right organisation, has threatened violence against Van Gujjars if they remained in the forests, accusing them of “land jihad.”

One vendor, requesting anonymity, said that the Van Gujjars are a victim of dirty politics. “Every time there is a discussion of relocating the Gujjars, this issue starts to rise,” he said. “This is deliberately done to stop the relocation. If the Van Gujjars are relocated, they would be given forest lands that comes within village boundaries. Most of these lands are occupied by the politically dominant villagers.” Indeed, records of discussions between the Saharanpur DM, the DFO and other authorities show that lands discussed for possible relocation of Van Gujjars lies within nearby villages.

The question of their relocation has arisen several times in official discussions. As early as 1979, the Uttar Pradesh government published a study by Chaman Lal Bhasin, a former forest officer, discussing the need for rehabilitation of Van Gujjars from the forest. Bhasin had proposed that each Van Gujjar family be given one hectare of land for cattle rearing and 500 square meters for constructing their house, at the fringes of the jungle. But the proposal was never implemented.

In 2007, a delegation of Van Gujjars wrote to the Saharanpur district magistrate requesting to limit the army to other parts of the jungle. “Since past 100 years, 20 families have been living in the Chapdi Khol area of the forest,” the letter read. The delegation never heard back from the magistrate’s office, a member of the delegation said.

The issue has persisted in recent years as well. The Saharanpur district magistrate headed a meeting on 9 October 2018, with his deputies and forest officials, to identify government land on the outskirts of the jungle to relocate the Van Gujjars who were living within the impact area of the Asan Field Firing Range. Another letter dated 4 October 2018, from the Saharanpur district magistrate to the DFO, shows that the district administration had even identified forest lands falling in village boundaries for relocating Van Gujjars. Nabi, the lambardar, said that Van Gujjars had not received any communication from the officials about this proposal. The district magistrate and the forest officer did not respond to queries about the same.

In 2019, Naresh Saini, the member of legislative assembly from Uttar Pradesh’s Behat seat, which is the closest constituency to the forests, wrote to the state secretary addressing the Saharanpur administration’s failure to rehabilitate Van Gujjars despite repeated assurances. In the letter, Saini expressed anguish on the killings of Van Gujjars inside the forest and cited a similar relocation done by the UP government in 1990 where 878 Van Gujjars were rehabilitated. “I want to bring to your notice that my constituency borders Uttarakhand where Van Gujjars in the area have been relocated in Haridwar city,” the letter read. On 19 July 2019, the state secretary forwarded the letter to the Saharanpur district magistrate, after scribbling “send urgent remarks” on the margins of the paper.

Saini pressed the issue in the legislative assembly again in 2022, a few months before he quit Congress to join the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party. He has not spoken of Van Gujjars ever since. Saini did not respond to multiple calls and messages seeking his comments.

But as Saini noted, the Van Gujjars have repeatedly requested to be relocated in light of the army firing, and the district administration has repeatedly assured them of it. There is even precedent for such relocation—in 2017, the Indian Army resettled 34 families residing in the target area of the Darranga Field Firing Range in Assam. While the Indian Army secured the lease for the Asan Field Firing Range without the consent of the Van Gujjars, Noor emphasised that the Van Gujjars would not think twice about giving the consent, if the provisions on resettlement were followed.

“Such practices are necessary for the army, how else will they win?” Noor said. “We are not saying that only we will stay in the forest and the army has to go. We only want peace in our lives. We want to be relocated to a safer place where our daughters and sons don’t die from bombs dropping from the sky. We want us to be safe, and our jungle to be safe.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the Tongias as a Scheduled Tribe community. The Polis Project regrets the error.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.