Abhishek Majumdar on His Amberdkarite Opera “Kavan” and Upcoming Novel “Radiodurans”

Abhishek Majumdar, award-winning playwright, director, and head of the theatre department at NYU Abu Dhabi, spent his early years at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), where his parents worked. He grew up studying science and mathematics while also taking an interest in the theatre and music that surrounded him on campus and at home. When he was done with college, he knew he would pursue theatre.

In 2005, Majumdar received the Charles Wallace and Inlaks scholarships and trained at the London International School of Performing Arts. He spent nearly a decade acting before he found his feet with Indian Ensemble, a Bangalore-based theatre outfit that he co-founded with actor and playwright Sandeep Shikhar in 2009.

Majumdar has since written, produced, and directed several internationally acclaimed plays. It began with the Kashmir trilogy (Rizwaan (2010), The Djinns of Eidgah (2012), and Gasha (2013), for which he travelled to Kashmir, conducting research and interviews for the plays. His practice has always been research-led. Political and human conflicts pique his curiosity and have taken him to many corners of the world, including prisons in China, for his play on the Tibetan struggle for freedom, Pah-La (first performed at the Royal Court Theatre, London in 2019).

In his memoir, Theatre Across Borders (2024), he recounts these journeys in searing detail. His plays begin with a set of questions—a hypothesis that he examines through multiple viewpoints and ideologies.

Majumdar has won many accolades, including the International Theatremakers Award New York, the Shankar Nag Award, and the Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META). He has created work across languages and geographies—with the National Theatre, London, Théâtre du Soleil Paris, and more recently, the San Francisco Opera.

His spirit of inquiry has once again led him to new material, and a new form. His latest, Kavan, an Ambedkarite opera produced in collaboration with Yalgaar Sanskrutik Manch (an Ambedkarite music group), examines the systemic nature of caste discrimination in Indian cities. It opened to stage calls of ‘Jai Bheem’ at its premiere at Mumbai’s Prithvi Theatre this February. The audience was a mix of the theatre’s regulars and Ambedkarite groups travelling from different parts of Maharashtra.

Majumdar had breached yet another frontier. An ensemble of performers from Yalgaar, songs of rebellion, and some uncomfortable silence marked the two days of shows. Kavan draws from experiences rooted in Yalgaar’s ethos to tell the story of its young protagonist, his rejection of a life of resistance, and his eventual acceptance.

It is a vibrant and multi-layered piece that uses music, dramaturgy, and video. Kavan is essential viewing and features some powerful performances by the ensemble cast. The music—in genres of folk, classical, rock, and rap—is as much of an earworm as it is powerful poetry. As a dramatic experiment though, Kavan stands on shaky ground. Its message rarely translates to the audience, making the plot appear more complex than it is.

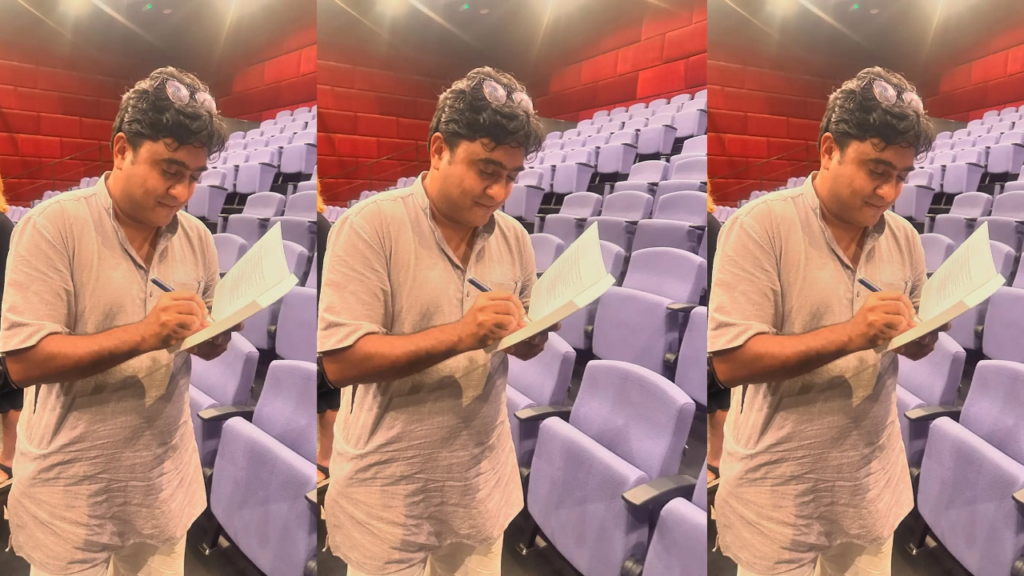

I’ve met Majumdar in many rehearsal rooms for over a decade. This one was larger and more crowded than the others. Everyone has a voice in his rehearsal rooms, but this one had more opinions and music. After a scene work session, we sat down for a chat over lunch. Over the week, we spoke several times, over a cup of coffee, on a Zoom call, and outdoors after a run-through of the play.

Majumdar is onto yet another experiment. He is writing the fourth draft of his debut novel, Radiodurans. It draws its name from a species of bacteria and is the story of an old woman in New Delhi and her undiscovered death. The plot takes place in different countries—and there’s a space station involved. He won’t go into much more detail.

Majumdar speaks to me about the novel, the two-year process, and the learnings that brought Kavan to the stage. Here is an edited excerpt of our conversation.

On Kavan

Prachi Sibal: How did the partnership with Yalgar Sanskrutik Manch come about?

Abhishek Majumdar: In 2018, Kunal Kapoor of Prithvi Theatre commissioned me for an adaptation of Prithviraj Kapoor’s Kisaan (1956). It was about the post-independent disillusionment of farmers. Dhammarakshit Randhive and actor Chhaya Kadam were part of the collaboration. Kisan looks at rural politics but not caste politics. I had read Marathi writer Daya Pawar’s Baluta (an autobiographical recounting of the Dalit experience published in Marathi in 1978), and we began getting interested in it as a project. The original project was stalled because of the pandemic. But Dhamma and I continued to dream about it.

Post-Covid, I got together with Birati Samuho (a queer performance group from Kolkata) and Yalgaar Sanskrutik Manch, to develop the project. Eventually, we decided to make two different plays.

PS: Tell me about the story of Kavan and how it came to be.

AM: Sudesh Jadhav (the writer of Kavan) started writing a story about a young boy, Bejul. He does not want to be a shahir (a performer of a folk form of protest poetry). His father was a shahir. That was an interesting perspective. We assume that people’s politics are already formed. We are creatures of habit, and most often, people take up the politics of the house, but that is not always the case.

His family dissuades him from Ambedkarite politics. His mother is very religious and wants him to be religious, too. It is about his journey as a religious person who goes from believing in destiny and that his predicament is a result of his actions to finally realizing his experiences are an outcome of a systemic failure and that he can play a role in changing it.

PS: Why did you choose the operatic form?

AM: I was working at the San Francisco Opera last year. I have also done Desdemona Roopakam, a chamber opera, in the past. I have a great interest in music.

In San Francisco, I realized that when we talk about opera, it is always in the Western context. There are many other kinds, like the Chinese opera, Tibetan opera, and those from Bengal and Assam. Utpal Dutt had also done a lot of Marxist opera in his time, and I loved that. Bengal has a big tradition of Jatra (a form of folk theatre with outdoor performances and an exaggerated style).

One of the conditions of an opera is that it comes from a specific school of music. The form of singing in this case was the Ambedkarite jalsa (a musical performance with folk songs and protest poetry). The music lends itself to the operatic straight away.

There also has to be an ‘epicness’ in the story. Epics themselves are often religious and come with inherent advantages. But Ambedkarite stories are epics in real life– with big movements and big journeys. So, I wondered what an Amberdkarite opera would look like. Why does opera have to be opulent?

It can also be an opera of the people.

PS: How would you describe Kavan visually?

AM: It’s like a concert that meets a play that meets a film. There are all three things on stage. It’s also the most tech-forward play I have made. Ambedkarite ideology was big on machines and industrialization, so philosophically, the use of technology was important. There are different visual styles, but it feels like a concert. Ultimately, some of the best theatre I have seen has been the Pink Floyd concerts. I have always wanted to direct a band. So, I am halfway there with this.

PS: How did your role as a director change in this production, where the story comes from—and is performed by—members of a marginalized community? What was the process with caste hierarchies and varied political views?

AM: This was not very different from Tathagat (2018) that I did with Jana Natya Manch. It was also not very different from Desdemona Roopakam (2021). There, I met Veena Appaiah, Pallavi MD, Bindhumalini Narayanaswamy, and Irawati Karnik and told them I was interested in Othello from Desdemona’s perspective.

I wanted to direct what they wanted to say. It is a role I am comfortable with. This was the case in Pah-La too, where the experts did the talking. Similarly, in Kavan. The masters of this text and music are Yalgaar. They took the lead, and we followed. When it came to decisions, the Yalgaar team had the first go at it. My responsibility was the theatre of it, not what was being said. I am very technical as a director.

The process was that of collaborative theatre. We created mini hierarchies depending on the role but didn’t have an overarching one. I am the director, and I had to have a say in what was kept and discarded. I needed to have the final cut. But, in the lead-up to that, there was a lot of discussion and debate.

For instance, on one occasion, we spent two hours discussing the ending. I asked the group what they would do in the situation. We had to be mindful that in an Ambedkarite opera, we were saying certain things about Yalgaar’s politics. Everyone wants equality. But when the oppressed do not get equality, is it justified to get violent? Is the onus of non-violence on the powerful or the oppressed? These are very contentious questions. These are things we had to deal with in the rehearsal room. Yalgaar is also not a single entity. It’s a group with varied opinions, and therein lies its strength.

PS: What preparations did your core team go through before embarking on Kavan?

AM: The strength of this group is that they are like sugar in water. You don’t see the grains. We have been in workshops for over two years. We read a lot of Ambedkarite literature. We read Baluta together. There were about 40 other works we read together. Irawati Karnik (dramaturg) was reading in Marathi, Pallavi MD (music composer) was reading Dalit poetry in Kannada, and I was reading in Bangla. We’d exchange notes then.

Fortunately, I read in Hindi and Bangla, which has given me access to Dalit writing in a way that English never could. It is the language of articulating thoughts and arguments, but very few first-hand experiences are written in English.

PS: What was the learning and unlearning during the process?

AM: We had to understand and learn Ambedkarite aesthetics. If somebody’s story is that of oppression, then who is getting catharsis in a tragedy? In the Ambedkarite aesthetic, catharsis would be defeat.

When Antigone dies at the end of the play, I go back to a metaphysical question. So, that catharsis is helpful. King Lear holding his daughter and crying in the end is similar. But, if it is a cobbler, and all his problems are rooted in caste, and he ends up crying with his daughter at the end, and I cry too, I have in a way absolved myself.

We had to learn to do tragedy without catharsis. In any drama school, we learn some form of tragedy, comedy, and clowning. But catharsis is in all of them. So, how do you change that? It was a very big learning experience. I had to ask them what they wanted to say at every step. These questions didn’t exist for plays like Kaumudi (2014) with single authorship.

PS: In what way does Kavan draw from the lived realities of Yalgaar’s ensemble? How does it push the envelope?

AM: In the play, Bejul stays awake at night and sleeps during the day. This came from a story about a delivery boy that was written during the process. He tells his mother that she sings a lullaby about the night coming to an end, but now that he has grown up and become a delivery boy, it doesn’t seem to. There were many such specific experiences that members of Yalgaar have had or have seen that informed my own understanding of caste.

As for the boundaries, Kavan talks about the Manusmriti (an ancient Hindu text widely criticized for its casteism and gender bias), while that is something Yalgaar doesn’t get to do with their own shows. With a play, we could be more radical.

PS: What was the biggest challenge of working on Kavan?

AM: The challenge of being oppressed historically is that when you make a piece of art, you are trying to reconstruct the person because they have been denied markers and subjectivity. There is no greater oppression than to deny people subjectivity, to have to be an objective truth all the time. There was a real attempt in the rehearsal room to regain this subjectivity. It was the most challenging and most interesting thing.

This extended to discussions on what kind of music Yalgaar plays. There is shahiri, an Ambedkarite form of protest poetry, but there is also rock and rap. Because everything in this space is political. Many times, tunes were changed, or instruments were added or replaced, not because of compositional issues but because of the ideology they represent.

PS: You have always believed in building multiple sides of an argument in your plays, as seen in both Pah-La (about the Tibetan freedom movement) and Gasha (about the Kashmiri struggle for freedom). Did the approach change with Kavan?

AM: With all these plays, including Pah-La, The Djinns of Eidgah, and now Kavan, I have been politically curious about the subject. They are existing problems and have multiple sides. I am not affected by them on a day-to-day basis, but I have empathy and concern. I also have an intellectual curiosity that acts as fuel.

I ask the questions that lead to these answers. So, the questions would be my contribution. Asking questions is my approach to anything. The history of great theatre makers is that of people being curious and asking questions, not subject matter experts.

PS: What is the plan ahead for Kavan? Where will it be performed?

AM: Part of the reason Yalgaar wanted to do this project was to perform in spaces they normally don’t. We have different versions of the play with high, low, and medium tech. It can be played at the Royal Opera House and on a terrace.

It’s coming to the Rangshila Theatre in Versova, Mumbai, in March. Following this, Yalgaar is organizing a bunch of shows in Ambedkarite spaces. We’ll apply to festivals, and next year in March, we are performing at NYU Abu Dhabi. We’ll probably plan a US tour, too.

On Radiodurans and Other Future Projects

PS: You’ve also written a novel that awaits publication. Tell me more about it.

AM: It’s the story of an old woman who lives alone in Delhi. Over time, she has cut herself off from the world. She orders everything online. One day, she dies. For the next two to three months, no one finds out. Nobody checked on her until her auto debit was working. Once it bounced, the bank sent someone and found her dead.

There is a lot of furor about how it could have happened and how irresponsible her children were. What kind of society is this? In the novel, you see everyone except her. You hear from her children, an astronaut, and people around her. You hear of their guilt and their explanations.

How do they survive an incident like this? In a society where we claim to care for elders and are less individualistic, an incident like this fundamentally questions our morality. It’s a book about shame, among other things. It’s about how much our lives are governed by what we are ashamed of and how it drives us.

It is called Radiodurans, after a bacteria that can survive in outer space. We think bravery and resilience come from large animals and beasts, but this is a bacteria without claws or any such things.

PS: Why did you write a novel and not another play? What was the process of transitioning from plays to prose?

AM: I have been wanting to write a novel for a really long time. I made some false starts. The things you can do with a novel are sometimes different from those you can do with a play. The focus on the sentence as a building block is very high. Everything is about the sentence. It’s an exercise I got fascinated with.

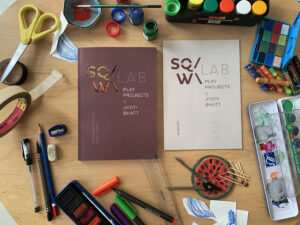

There are some things as a playwright that worked to my advantage, and one of them is dealing with time. Playwriting is essentially about structuring time. However, I wasn’t used to having to create everything with words. It’s very hard but also a lot of fun. A friend gifted me a Masterclass a few years ago. It had one by Salman Rushdie on novel writing. I kept revisiting it and took away different things from it each time.

My focus was always on the narrative, but I slowly realized that everything in a novel is about the language. I went on the internet and searched ‘How to write a sentence?’ I spent the next six months just writing sentences in different ways. It’s an exercise that helped, and I now have notebooks full of sentences.

The next step was research since the novel is set in Delhi, the UK, the US, and a space station. I also knew that my characters spoke different languages. I created a visual map of their worlds and wrote the first draft in 2023. I am now working with an editor on my fourth draft.

PS: What other projects are you currently working on?

AM: There is a prequel to Pah-La that I am writing, which will open in India in 2026. I am working on a play, a documentary piece about a man who was detained in Guantanamo Bay. I am directing a dance piece in Brazil. I am also working with a playwright from Syria on a three-part play that I will be directing. I am writing a Hindi play, Juno 77, set on an asteroid. It is about morality and astrophysics.

Lastly, there is a play in Kerala where I will work with the traditional form of Ottathullal (an 18th-century form of dance and humor developed by poet and performer Kunchan Nambiar). It will be co-directed by Sreejith Ramanan of the Thrissur School of Drama. I am directing a piece for Birati Samuho next. It’s a project I am really excited about.

But, other than the dance piece, I’ve kept everything at bay to finish the novel. With theatre, things are timed, and people are always waiting. I am good at juggling theatre projects, but with the novel, it’s different. Nobody is waiting for my novel. In fact, many of my collaborators are losing patience.