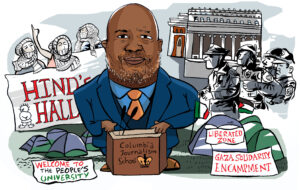

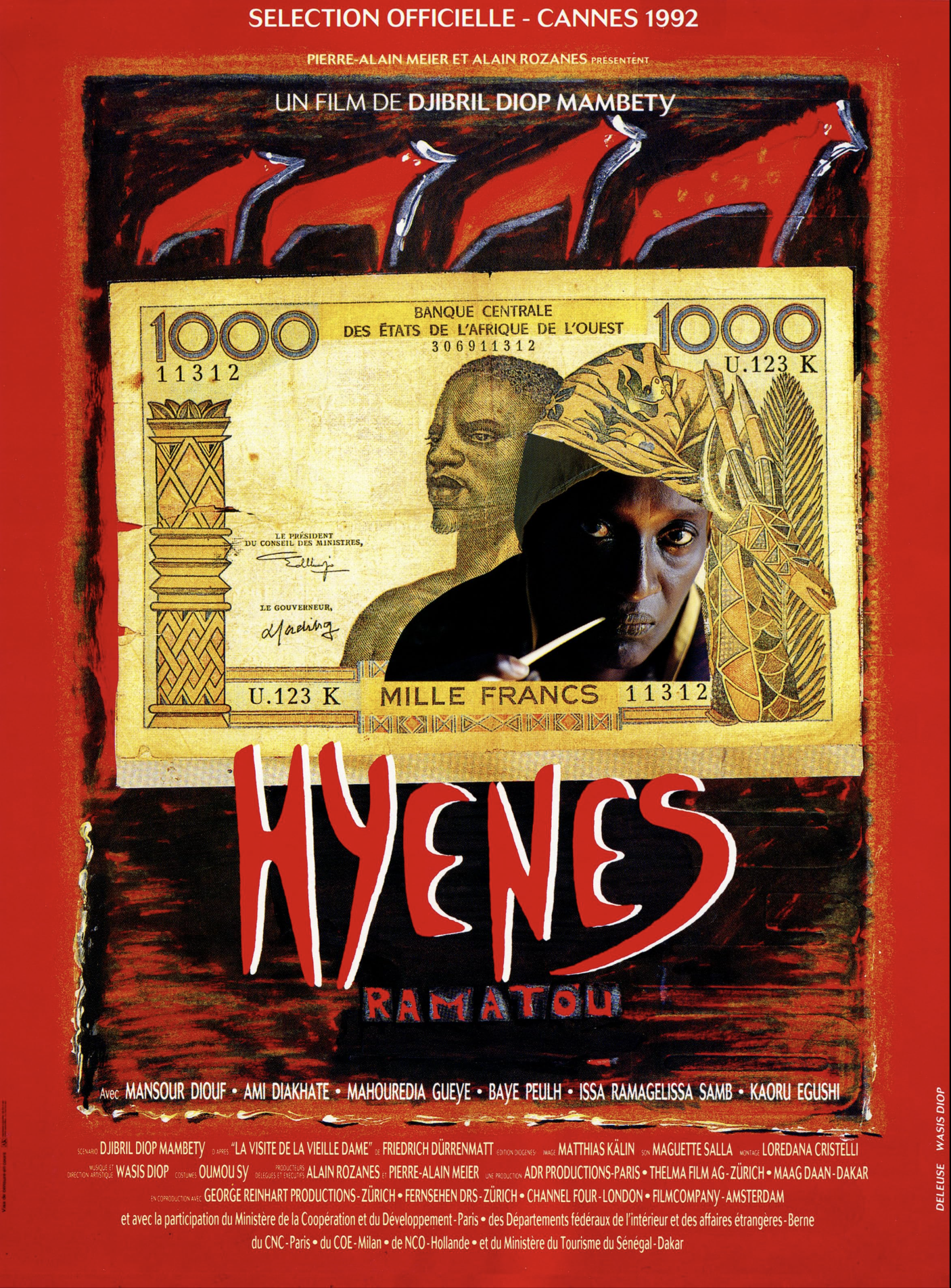

Hyenas: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s 1992 Masterpiece Reflects The Anger Of The Spurned

Djibril Diop Mambéty’s 1992 masterpiece, Hyenas, is a film about people being pushed to their breaking points. A loose adaptation of Swiss dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit, the film’s central conflict is the relationship between billionaire Linguère Ramatou (Ami Diakhate) and local shopkeeper Dramaan Drameh (Mansour Diouf). Once young lovers, Linguère returns to her birthplace, the village of Colobane, with a simple offer for its inhabitants: she will invest “a hundred thousand million” into the village on the condition that they kill Dramaan, the man who used the corrupt and patriarchal judicial system to exile her from Colobane after he impregnated her.

Full of biting black comedy and heartbreaking destruction, Mambéty engages with the classic philosophical question: What do we owe to each other? The answer, in the context of the colonially-imposed neoliberalism of Mambéty’s native Senegal, is nothing.

Everything in Hyenas is transactional. The village of Colobane is rundown, in disrepair, full of people scraping by in the wake of their liberation from their French colonizers. The money Linguère offers is much needed, and in a world where capital determines freedom, the calculation becomes obvious.

One of the darkest—and funniest—jokes in Hyenas is how quickly the Colobane people make their decision to condemn Dramaan: Mere minutes after Linguère makes her offer, the villagers enter his shop to order the most expensive items on credit. “In life, as in death, solidarity,” says the local beggar to Dramaan as a show of support, even as he notes that he only drinks imported Simon Leynan cognac now. “Put it on my tab,” he insists. “You won’t be here to collect it”, you can hear him imply.

The conditions of neoliberalism that Mambéty castigates in Hyenas result in a populace forced to privilege the promise of economic redemption over their own sense of morality. Faced with the rampant inequalities imposed on a society (in Colobane, in Senegal, in Africa), and the destruction of systems of intra-community trade in favor of foreign ‘aid’ and the supposedly-impartial free market, the only recourse left is to try and scrabble desperately onto the lowest rung of the new economic order.

Mambéty cleverly takes moral philosophy and makes it horribly grim and astoundingly funny: would you pull the lever in the trolley problem if rather than saving five people, you simply got to save yourself?

Hyenas is no simple tale of heroes and villains. A lesser movie would make Linguère irredeemable, a person whose grand bargain is a self-serving way of taking petty revenge. Instead, throughout the film, Linguère’s actions are shown to be the product of justified anger in response to having politics enacted upon her. Faced with the removal of your humanity and autonomy at the tender age of 17, Mambéty suggests that the only natural development would be to become someone who wishes to wield their newly economically derived power over others.

“Who can abolish time?” Dramaan asks Linguère, wondering why she has held on to this burning desire for vengeance for so long. And while she answers, “I can,” the film’s events do not bear that out. All Linguère can do is express her rage, respond to inhuman treatment with inhuman treatment, and argue that restitutive justice is the only way for things to become equal. Isn’t that all anyone can do?

Throughout Hyenas, the proposed murder is largely discussed in economic terms. “I want us to settle our accounts,” says Linguère to her former paramour. “You have chosen your life and you have imposed mine upon me.” The only way to concretely express your anger in the world of Hyenas is to win the economic battle. Your access to money informs your power, but that money cheapens the soul.

Towards the film’s end, the emotional underpinnings of Linguère’s anger become even more heartbreaking. Buoyed by Diakhate’s superb performance, we see a woman who doesn’t want to walk the path of vengeance but sees no other way to reverse the injustices of history. She must take what she is owed, even at the cost of her moral rectitude. Just before the film’s tragic coda, Linguère tells Dramaan, “You’ll be mine forever. You belong with me.” The intermingling of desire, possession, despair, and regret is clear.

Even as she proclaims lines like “the world has made me a whore and I’ll make the world a whorehouse,” and, “you’ll cover your hands with blood or remain poor forever,” Linguère’s curse is to know that she will drag both herself and Dramaan into the dirt. Diakhate’s furrowed brow and slump of her shoulders carry the same message: There is no other way.

Her always-justified anger has curdled, reducing a man to nothing instead of enriching her own spirit. Mambéty, a stalwart of post-colonial Senegalese cinema, understandably sees the conditions of Western-imposed neoliberalism as something that begets violence, that forces humanity to turn towards self-interest and vicious expressions of rage. “Hell?” asks Linguère. “I am hell!” But this is not a hell of her own making. At the end of another scene, the town’s inhabitants use Dramaan’s panicked exit from his shop to steal his wares. Amidst the chaos, Mambéty cuts to a shot of a monkey playing with the French flag.

When Dramaan eventually succumbs to his death at the hands of the Colobane people, it is without bloodshed. In Hyenas, we do not see the actual viscera of his murder. Instead, we see a crowd slowly envelop the poor shopkeeper, encircling him until we lose sight of him. Mambéty cuts to Linguère as she watches, showing no joy at the culmination of her lifelong project, but more a resignation that such events were necessary. By the time Mambéty cuts back, Dramaan is gone; all that’s left of him is his coat, abandoned to the desolate Senegalese desert.

After all, this was not an act of violence, but simply the free hand of the market. It leaves no trace of what it has wrought.

In the broader cinematic context, we can often discern a reactive streak in the filmic tradition that comes from populations who have suffered under violence, colonial or otherwise. Art is by necessity created in opposition to a politics that has been done to them, rather than led by them. Anger, struggle, and the desire for vengeance are presented as the natural consequences of political structures being imposed on citizens. This directly opposes the wishes of the dominant neoliberal ideology, which does not see politics as made up of people with intensely felt emotions and sufferings but composed of the technocratic solutions it proposes.

According to Frantz Fanon, this is why passive resistance is so celebrated by the ruling classes. “All those saints who have turned the other cheek, who have forgiven trespasses against them, and who have been spat on and insulted without shrinking are studied and held up as examples,” he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth, his 1961 examination of colonial psychology.

This is not the case in Hyenas. Rather, it presents characters who refuse to turn the other cheek, whose post-colonial sufferings are not met with meek acceptance, and whose internal fire is lauded because it is a reaction to the strictures that encroaching capitalistic society has placed upon them. Mambéty’s characters are not who we want to be, but they’re forced into being who they are because of the emotional, mental, and physical violence that colonialism and capitalism have placed upon them.

In Hyenas, Linguère Ramatou has made something of herself and escaped the horrors of her upbringing. She is investing in the area that raised her. That it must be caveated with an equally horrifying demand for retribution is a result of her earlier subjugation. She is requesting the destruction of the civilized order because she has nothing else left to request.

The failures of neoliberalism have been made abundantly clear in the recent US Presidential Election. Despite being centered on the specific struggles of the Senegalese people after their independence, Hyenas seems so timeless and relatable because it speaks to larger truths about how humans react as they see their material conditions worsen.

When the accumulation of capital is presented as the only feasible means of salvation, it follows that society would reorganize itself around the person who promises to offer them a means of accruing it. Self-interest becomes the primary animating force of an entire community, and the question of “What do we owe to each other?” is replaced with the tangential query of “What do I benefit the most from?”

Towards the end of Hyenas, when Colobane’s citizens convene to vote on Dramaan’s murder, Mambéty’s mordant humor comes to the fore again as they twist themselves into knots trying to justify their actions. “We’re doing this because what Dramaan did 40 years ago was wrong,” they insist. “We’re doing this because we believe in the principles of justice.” The moral equivocations reach their peak when a town elder notes, “The donation is accepted, not because of the money, but to be in agreement with our hearts.”

Ironically, this is the most truthful justification of all. To “be in agreement with your heart,” in the world of Hyenas, in a world whose social bonds have been severed by the encroaching specter of economic doom, is to choose a path of financial gain. It’s not about the money. That would imply that you had a choice. As Linguère herself says earlier on, mulling over the panic she sees in the streets of Colobane: “The reign of the hyenas has come.”

(Hyenas has recently been made available to stream on Kanopy and Metrograph).