In 2009, in what was perhaps the first punitive demolition in recent years, Indian paramilitary personnel destroyed the Vanvasi Chetna Ashram, a non-profit welfare centre for locals spread over 16 acres in Kanwalnar village, near Chhattisgarh’s Dantéwāḍā district. Over 17 years, the centre had served the minimal needs of the Adivasi populace, such as healthcare, nursing care, primary education, elementary vocational training, and ultimately also the housing and legal needs of those displaced in the wanton destruction of huts and villages inflicted during anti-Maoist operations. The next year, the noted Gandhian activist who ran the centre became a tadipaar, forced to migrate to a safe zone, never again able to rule out further trouble, including arrest. He became known for flagging, without fear or favour, the state’s vigilante militia and militarisation in the Bastar region. On November 22 this year, the deportee from the Maoist heartland, Himanshu Kumar, now 60, completed a nearly 2,000-kilometre cycle march through western India.

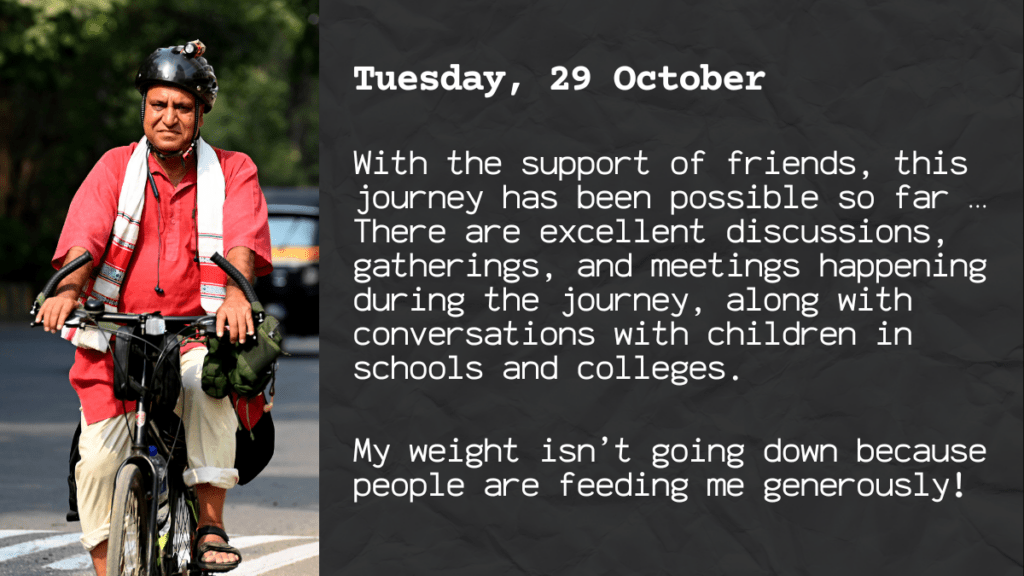

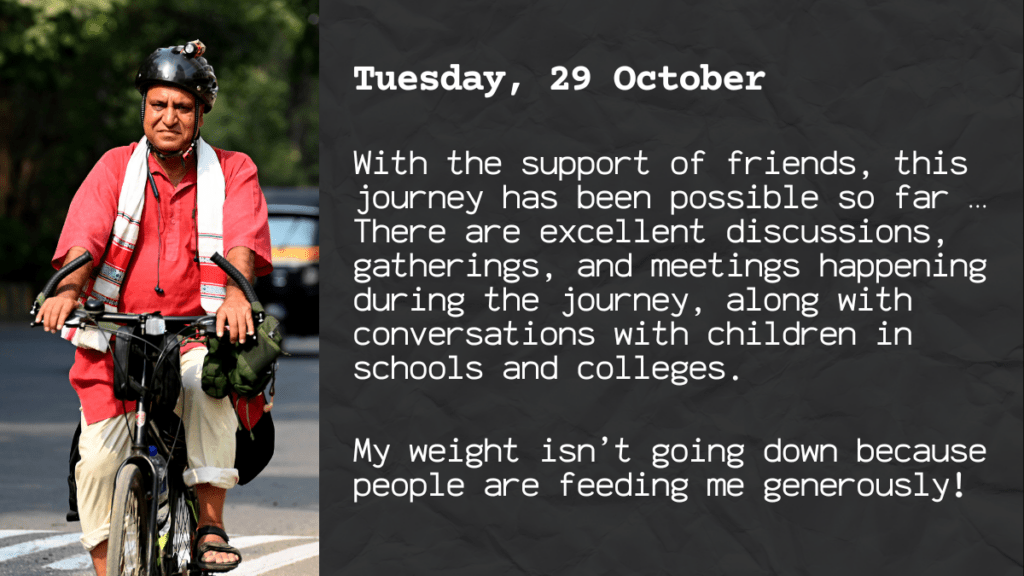

The sexagenarian’s gruelling ride, through the western countryside, brought back memories of grassroot campaigns from decades ago. Back then disparate groups of activists “went to the people,” raising dissenting voices across the country against the anti-people policies of successive regimes, as a means to mobilise the masses for popular agitations and movements. Times, however, have changed quite a bit, and Kumar had to go all alone on the long ride from Delhi to Mumbai. He traversed the distance on a bicycle fitted with gears to climb flyovers and negotiate hilly curves and undulations, a torch affixed atop a sleek black helmet, while wearing Bluetooth earphones providing him a constant connect with the world at large. Of course, he also had an agenda to build up, invoking his own ordeals in the hope that it could lend a wider canvas for various local inhabitants to discuss the ongoing struggles against their own injustices. Throughout his journey, he would relate with myriad oppressions at the many doorsteps where he parked his bicycle.

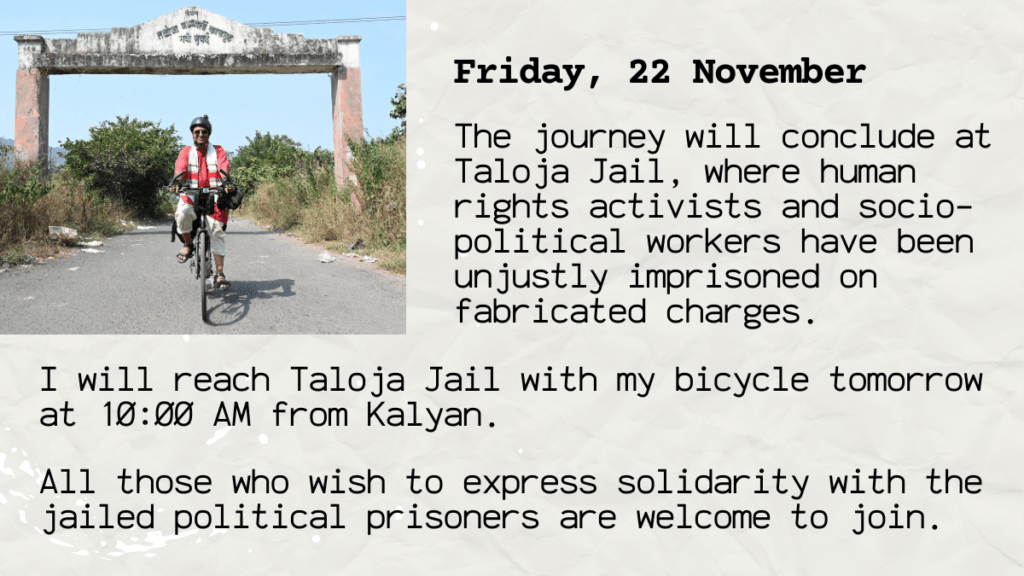

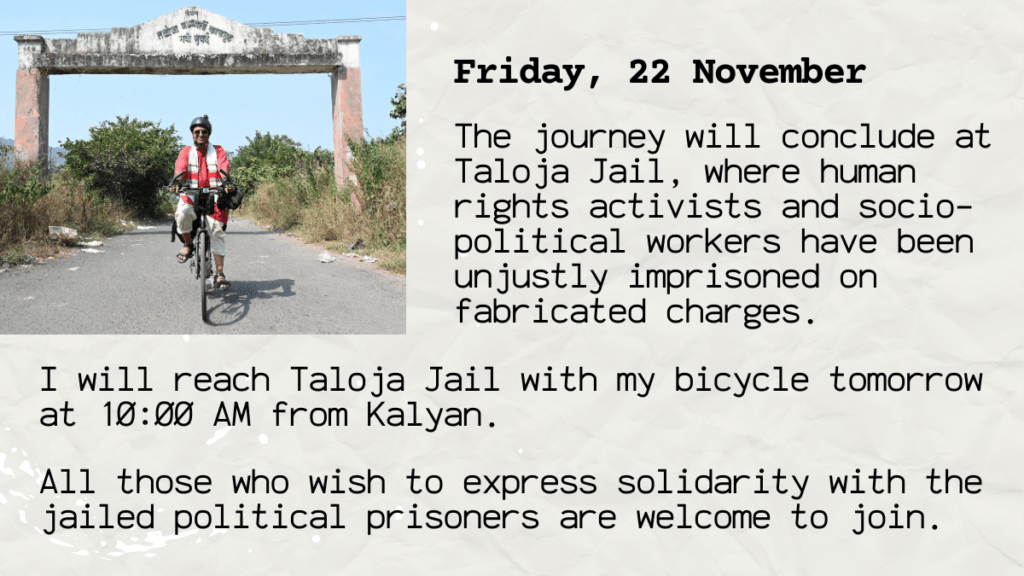

The Polis Project has been following his mission right from its beginning on October 2, the birth anniversary of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, when he set off from the Rajghat Memorial at Delhi. Before leaving, he symbolically spun cotton with a hand-driven charkha, surrounded by a handful of supportive co-activists. Through his journey, Kumar remained connected with people, and routinely posted eye-opening reports, until he reached his destination—the entrance to the premises of a blighted central prison—at Taloja, close to Navi Mumbai, 52 days later.

His first overnight halt in his journey was at the indefinite sit-in by scores of terminated workers from the Maruti Suzuki car manufacturing plant, in the Manesar industrial borough of Gurgaon, which is still continuing 12 years later. In the ensuing days and weeks, Kumar traversed, all by himself, through the communally sensitive Mewat region, straddling south-east Haryana, the eastern tip of Rajasthan, next to Mathura, and went on to central Rajasthan, before heading southward, while mingling particularly with the Adivasi and Dalit indigenous populace all along, into eastern Gujarat. Meandering around, he cycled towards the Statue of Unity, and entered Maharashtra through the north-west of the state.

At various locations, Kumar made notes and shot videos on what the locals had to say about the government’s high-profile development projects and how they brought about devastation instead. He noted how these projects generated little hope for the people’s welfare, jobs, or any progress whatsoever—not even in the form of basic amenities such as toilets, village roads, primary schools, and healthcare. Meanwhile, the promise of allotting independent land to the individuals displaced by these projects remains unfulfilled. Land that by and large still belonged to feudal landlords, who diversified into money-spinning businesses, hardly spurring a regenerative economy. His posts and videos are worth a peek for those who would wish to comprehend the lives of whom we, the city-bred, call “the marginalised.”

The destination for the cycle march was a choice that emerged from a strong conviction. One of Kumar’s intentions was to prick the nation’s conscience over the languishing predicament, since early 2018, of “the 16 best minds of the country.” Of them, seven men and one woman still remain behind bars—the former in Taloja Central Jail and the latter in Byculla Women’s Jail. They are none other than those known, in many quarters by now, to have been falsely implicated in the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case: eminent authors, lawyers, professors, poets, song composers, theatre artistes, and researchers, most of whom doubled as activists, from different parts of the country.

Quality reams have been printed and gigabytes uploaded in the public domain about how, and for what nefarious purpose, the case was concocted under the previous Devendra Fadnavis government in Maharashtra. Credible forensic analyses and rational logic strongly suggest that the incriminating documents, purported as evidence, could only have been fabricated and implanted by state agencies, possibly assisted by non-state hackers, on the computers used by some of those arrested, none of whom has been granted bail as yet. Some of those “best minds” would soon complete seven crushing years in prison. One of them, Stan Swamy, known to have been a Jesuit priest most of his life, and also a beloved social activist and prolific writer, whose computer had apparently been compromised earliest of all—since 2014—could not survive his incarceration.

Kumar has been making valiant attempts to keep apprising people, every now and then, of many such disturbing facts, which have too short a shelf life in today’s mainstream media. His choice of the destination helped him veer conversations with the people he kept meeting, along his cycle tour and even after it, around the tragic misuse of the law and the prevailing criminal justice system.

In a quick interview with The Polis Project, at a Taloja studio, hours after reaching his destination, Kumar further explained that his choice of Delhi as the starting point of the cycle march was also similarly motivated. He wanted to draw the attention of people to the toxic targeting, wrongful arrests and prolonged incarceration without bail of a number of well-meaning, Delhi-based young leaders—mostly Muslim men and women, but also a few secular non-Muslims—in late 2019 and early 2020. Many of them played key roles in the popular protests that had gripped the country, against the anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act. The protests were forcibly withdrawn, in the face of a suddenly imposed lockdown, just when the early version of the COVID-19 virus struck India. But the Delhi pogrom, engineered around the time of the US president Donald Trump’s visit, became the smokescreen for many vindictive and communally tainted arrests. More than a dozen of those anti-CAA democratic agitators still languish in prisons, nearly five years down the line.

Kumar also drew the attention of his audiences to the more recent National Investigation Agency arrests in Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Chandigarh—with the agency still punching, allegedly beyond its calling. The NIA has fixed its scrutiny on another batch of activists—some of whom have been writing, practising legitimate professions, organising workers, or simply studying—accusing them of conspiring with a leading body of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist).

Deprivation in the name of counter-insurgency

Himanshu Kumar is no stranger to the state’s tactic of associating social activists with banned organisations. He faced the same situation while running his Vanvasi Chetna Ashram in Dantewada, the southernmost district to be carved out from Bastar. In July 2022, a Supreme Court bench of AM Khanwilkar and JB Pardiwala dismissed his 2009 petition seeking CBI investigations into the brutal massacres of innocent Adivasis in three Dantewada villages—Gachhanpalli, Gompad and Belpocha—on September 17 and October 1, 2009. The petition described the specific incidents in vivid details, and identified the perpetrators as Chhattisgarh Police, Central Reserve Police Force and its COBRA battalions, and Salwa Judum—a state-sponsored anti-Maoist militia, which was declared unconstitutional in 2011, and was therefore temporarily disbanded, only to be allegedly reconstituted as a District Reserve Guard. Yet, the Supreme Court bench not only dismissed the 2009 petition, but also slapped an “exemplary cost” of Rs 5,00,000—equivalent to over 6,000 in Euros or US dollars. The judgment, authored by Justice Pardiwala, took elaborate note of the current regime’s top prosecution counsel, Tushar Mehta’s allegations implying that, by levelling such grievous accusations against the state forces, Himanshu Kumar had been aiding and abetting the “heavily armed” Left-Wing Extremists (or Naxalites). The apex court stopped just short of initiating criminal proceedings on this count, though it made no bones about its displeasure against Kumar. A review petition against the judgement has also been dismissed.

While Kumar declines to pay the fine, he continues to circulate reports, until date, of incessant—in fact, escalating—alleged atrocities by the CRPF, COBRA, the Border Security Force, and the District Reserve Guard, all of which would seem to violate the fundamental right to life, liberty and livelihood, particularly in Bastar and its surrounding areas, in the name of counter-insurgency operations. He maintains that the military operations being advanced by the state are part of a corporate conspiracy to seize the forests and hills of central and eastern India, aimed at satisfying the rapacious greed of mining interests, both in India and abroad. The deprivation of the entire gamut of fundamental rights of the indigenous inhabitants are considered mere “collateral damage” in this reckless and violent endeavour.

According to Kumar, it was only incidental that just when he and his wife had succeeded in putting into place multiple welfare activities for the Gondi-speaking Adivasis of Dantewada, the government policies of “liberalisation, privatisation, globalisation” (LPG) came into full swing. “Chhattisgarh government had signed over 100 MoUs with investors” at the beginning of the current century, he observed. “Many of them were for mining projects in the Bastar area.” Kumar explained that this created a conflict because the indigenous people of Bastar posed a threat to the extraction of minerals from their land and forests. “So, the state constituted a private army, under the garb of Salwa Judum—which in Gondi meant, ‘a campaign to establish peace’—in order to pre-empt the inevitable peoples’ resistance.”

In the Nandini Sundar case, the Supreme Court ruled against the vigilante force, but the government simply inducted the Special Police Officers from Salwa Judum into an official District Reserve Guard, believed to now operate as a key component of the basic forces on the ground, under the unified command for central India, in military terms. “The SPOs, being Adivasis themselves, are now committing the same sort of atrocities as regularised personnel.” The basic military force of the state, till this day, thus seems to be composed of the former Salwa Judum personnel.

A couple of years ago, the Gondi Adivasis organised themselves as an independent collective called the Moolwasi Bachao Manch. Over the last three years, the Manch has been actively and effectively manifesting the demands and aspirations of Bastar’s local populace, to resist the aggressive state militarisation, with sheer bravado in the fast-shrinking democratic space. But towards the end of Kumar’s cycle march, this platform for peaceful struggle was also banned as an unlawful organisation under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005, accusing them of causing obstructions to the “developmental activities” of the state. Kumar has been inconsolably disturbed by recent reports of the wanton detentions, especially at unknown, undeclared centres, for indefinitely long periods, besides the illegal arrests and torture of the supporters of the Manch, particularly the younger women, and the bombing of fields of peasants around paramilitary camps. These are some of the many secrets that Kumar has tried to share with the indigenous people of western India, and beyond, in the course of his cycle tour.

Resilience against communal strife

When asked how he drew his courage, Kumar narrated a story of his elder uncle, Brahma Prakash Sharma, an advocate in whose honour a gate stands in the compound of Muzaffarnagar District Court, his native city in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Sharma, he recalled, had also been slapped a fine for alleged contempt of court in a petition flagging judicial corruption. “If my uncle was respected in Muzaffarnagar for his courage in taking up cudgels against judicial dishonesty, how can I be cowed down by such chicanery?” There was an uncompromising flourish in his challenge to the state.

Kumar’s father, Lakshmendra Prakash Sharma, who was also known as Prakash Bhai, was a trusted pupil of Gandhi himself, having studied in his first batch of Nayi Taleem. Prakash Bhai also participated in the 1942 Quit India movement, and the Bhoodan Aandolan launched by Sarvoday architect, Vinoba Bhave, in a bid to persuade landlords to voluntarily surrender their excess land to their landless peasants. Both parents followed Gandhi’s direction to the youth to perform social work in villages. So, they immersed themselves in serving villages in their home state. Kumar carried forward his parental legacy, settling deep inside present-day Chhattisgarh in 1992 with his newly-wedded wife.

Kumar attributes his existential choices mainly to his father and mother, but also to his great grandfather, Bihari Lal Sharma, a school headmaster. Among the select few educators of his time, the doyen of Kumar’s family actually authored a rare, Persian work of fiction, named, Ajeeb Khaab, a fantasy about a secular future. Kumar’s secularism manifests in his oration as well: his Hindi happens to be well enmeshed with its Persian component—he speaks perfect Hindostani, rather than the deliberately Sanskritised version of Hindi.

As he paddled his way into the Mewat region, Kumar was conscious of Gandhi’s role in winning over the predecessors of today’s Mewati Muslims. Faced with the dilemma of whether or not to cross over to Pakistan during the Partition, as many of their religious brethren from then East Punjab had been compelled to, Gandhi is said to have asked them, “Is God different in Pakistan than in India?” Ever since, the Mewati Muslims have generally embraced Gandhian initiatives, said Kumar.

Paramita Ghosh has discussed the syncretic culture of the Hindus and Meo Muslims of Mewat in a Hindustan Times article published in the wake of an incident from August 2016, when alleged cow vigilantes gangraped two Meo-Muslim girls in a Nuh village. Ghosh pointed out that it was PC Joshi, a leader of the then undivided Communist Party, who had introduced the leader of the Meo Muslims to Gandhi, implying Communist support in helping consolidate Meo Muslim bonds with India. The 2016 attack had “reopened old wounds,” she wrote, referring to the nostalgia over “common rituals” shared by Meo Hindus and Muslims in the not-too-distant past, and how it has endured multiple efforts to create fissures over the last century.

Kumar emphatically acknowledged the resilience of Meo collaboration across the religious divide, however much the fanatics may have damaged it. He referred to the infamous lynching of Pehlu Khan, a cattle trader from Mewat who was brutally assaulted to his death in April 2017 by cow-protection vigilantes, while speaking wryly of the divisive moves afoot to tear asunder the cultural fabric of the indigenous communities of Mewat. He remarked how the days he spent in the Mewat region—from Nuh in Haryana to Dausa in Rajasthan—made him realise that “the Muslims are as indigenous to the Mewat as the Hindu Jats, Gujjars and Meenas.” He found little difference in their way of living, customs and traditions. “Regardless of their religious denomination, the Mewatis have had the same agrarian and pastoral occupations, cooked in the same way, and commonly observed their festivals in mutual celebration.”

Since time immemorial, a traditional, 84-kos—a measure of distance varying from about two to three kilometres—circular pilgrimage, or parikrama, of Hindus, in Mewat has been serviced by the Muslims with equal gusto. To this day, sweet drinks and other consumables catered by Meo Muslims help the Hindu devotees complete the pilgrimage, offering a major source of energy and comfort. However, a much more strident form of the earlier Chaurasi Kos Parikrama, called the Brij Parikrama, replete with eardrum-shattering music and aggressive posturing, was launched a few years ago. In one of his many conversations with Kumar, Zafar Yaduvanshi, a Meo peasant leader from the national body of the farmers’ collective Samyukta Kisan Morcha, points how this newer version intentionally stokes the flames of anti-Muslim belligerence.

But has the fanatics’ alleged conspiracy and stridency inflicted any permanent damage so far?

Communal strife has been increasingly trumped up over the past decades in the mainstream media, noted Kumar, adding that on the ground, the scenario remains complex. He spoke of the failure of Hindu fanatics to inflame religious passions beyond a limit. Still, at a gathering of Sarvoday volunteers in Mumbai, on November 26, he admitted, in reply to a pointed question, that the situation could not be taken as lightly as Rahul Gandhi’s populist posturing with the use of phrases such as “Mohabbat ki Dukaan”—a Shop of Love. The way out of the effects of hate mongering would have to be found more diligently, he averred. Yaduvanshi, who was at the helm of the popular farmers’ movement, suggests that the only way to defeat the divisive forces was to consistently devise ways and means to struggle, in a symbiotic manner, for the rights of the toiling masses against the exploitative policies of the current regime.

In one of his posts, Kumar wrote that in Mewat, he “enjoyed the hospitality of homes, mosques, and madrassas” of Muslims. In the Meenawati region, it was the “homes of the Meena tribal community,” that drew him in, to “discuss and understand their lives,” as he headed into the heart of Rajasthan. The Gandhi Darshan Committee, the Satyagraha Committee, Congress workers, and others helped him organise anti-communal meetings and deliberations at various public places, and also helped him organise his food and rest, in addition to members of a Tribal Coordination Committee, who oversaw his tour from the start to finish.

Gujarat, meanwhile, lived up to the reputation of its authoritarian government, as sleuths constantly harassed the members of Kumar’s local support network, calling them up, not once or twice, but every few hours to ask about his whereabouts and the minute details of his activity. During a previous ride through the state, when the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah duo served as chief minister and home minister, he had been bodily transported along with his bicycle in a vehicle right into Maharashtra. The phone calls did not help ease the bitter memory of that past.

More importantly, Kumar found to his alarm a dispute over the figurative Statue of Unity, meant to commemorate the Congress “iron man” Vallabhai Patel. He exclaimed that “Adivasis are prevented from building huts, even toilets, under provisions of a Statue of Unity Act!” Land was reportedly taken over from Tadvi Adivasis, in the vicinity of the statue, after first persuading them to give up their animistic worship of nature, citing a false demographic threat to Hindus. Once they adopted the majority faith, their lands came to be acquired for restaurants, hotels and resorts, built by capitalists, to serve an elite clientele. It was only later that they realised that they were hoodwinked into subservience according to a game-plan of the ruling party, and its ideo-political objectives. Kumar wondered if the constitution of Bharat Adivasi Party could be a reaction to precisely such Hindutva realpolitik. “The BAP now has representation in Parliament and the Assembly,” he pointed out with glee.

Kumar lost no opportunity to engage with the Hindu youth too—and he met quite a few as he pedalled along—taking pains to explain to them how they were actually being used for nefarious ends. “By provoking them to be aggressive at the time of Ram Navami processions, for instance, to hurl abuses at, or physically attacking, the minorities for no sane reason, a substantial section of the youth was being criminalised,” he argued. “In the long run, even if the powers-that-be may derive political gains and stay in power for a few more years than they deserved, it would disunite the country through and through.” Forces opposed to the real criminalisation have been increasingly subjected to fake criminalisation under repressive Acts and a sectarian police machinery, with the judiciary not helping, the Gandhian maintained.

Presenting details of his halts along the course of his paddling experiment, Kumar specified, in one of his posts, the secret of his high spirits, and why he could get by without any hurdle, “Among my friends are people from tribal, Muslim, Dalit, Gandhian, leftist and Congress backgrounds, along with those involved in social movements, including farmers, labourers and women’s movements.” With such a varied array of support, he hopes to find the social, political and economic way out of the problems facing the country under the current regime.

“Only twice did my cycle need a patching up of punctures,” Kumar said, as he retold stories of how his tyres rolled across rivers and mountains, along both fertile and arid zones, farms, woods and mangroves, puffing through the dusty Aravallis and exerting up the granite slopes of the northern Western Ghats. All along the journey, he surveyed the landscape, interrupted by the wounds of devastation caused by a profusion of development projects, destined to serve the rich and privileged, while severely impairing the poor and underprivileged inhabitants of, and around, a substantial part of the acquired land and forests.

Kumar did not fail to take notice of the endless struggles, individual and collective, of virtually every section of the toiling masses, for their basic right to life and livelihood, in pursuit of the mirage of equal opportunities, and for their freedom of belief and dissent. That, in fact, was his main conclusion, though he seemed curious about the different forms of struggles being adopted across the country. The state, nonetheless, remained impervious, I retorted, in a private conversation with him. He lost no time in correcting me, “The ruling BJP, in all the states that it rules today, pounces upon the slightest opportunity to create rifts and conflicts out of non-issues, in a desperate bid to divert the toiling peoples’ attention from the basic issues that concern their lives and livelihoods: the lack of jobs, the spiralling prices, and no real development in terms of amenities for themselves.” This, he suggested, was a demonstration of an endemic weakness that has gripped the state; an insecure state could not bode well for any positive development.

Many such conversations appeared to have been generated in the wake of the cycle march, in the context of the mutually shared desire of the many activists and social scientists, who continue to interact with him, with an eagerness to help catalyse a process of positive change.

An unmistakable takeaway at the end of the march was, as Kumar put it, “It has strengthened my resolve, my physical condition, and also my confidence.” For a chronic patient of Myasthenia Gravis, a troublesome neuromuscular disorder, the solo 2,000-kilometre-long cycle march was nothing short of what his physician called it—a miracle.

Related Posts

Himanshu Kumar’s cycle march from Delhi to Mumbai continued his legacy of advocacy against oppression

In 2009, in what was perhaps the first punitive demolition in recent years, Indian paramilitary personnel destroyed the Vanvasi Chetna Ashram, a non-profit welfare centre for locals spread over 16 acres in Kanwalnar village, near Chhattisgarh’s Dantéwāḍā district. Over 17 years, the centre had served the minimal needs of the Adivasi populace, such as healthcare, nursing care, primary education, elementary vocational training, and ultimately also the housing and legal needs of those displaced in the wanton destruction of huts and villages inflicted during anti-Maoist operations. The next year, the noted Gandhian activist who ran the centre became a tadipaar, forced to migrate to a safe zone, never again able to rule out further trouble, including arrest. He became known for flagging, without fear or favour, the state’s vigilante militia and militarisation in the Bastar region. On November 22 this year, the deportee from the Maoist heartland, Himanshu Kumar, now 60, completed a nearly 2,000-kilometre cycle march through western India.

The sexagenarian’s gruelling ride, through the western countryside, brought back memories of grassroot campaigns from decades ago. Back then disparate groups of activists “went to the people,” raising dissenting voices across the country against the anti-people policies of successive regimes, as a means to mobilise the masses for popular agitations and movements. Times, however, have changed quite a bit, and Kumar had to go all alone on the long ride from Delhi to Mumbai. He traversed the distance on a bicycle fitted with gears to climb flyovers and negotiate hilly curves and undulations, a torch affixed atop a sleek black helmet, while wearing Bluetooth earphones providing him a constant connect with the world at large. Of course, he also had an agenda to build up, invoking his own ordeals in the hope that it could lend a wider canvas for various local inhabitants to discuss the ongoing struggles against their own injustices. Throughout his journey, he would relate with myriad oppressions at the many doorsteps where he parked his bicycle.

The Polis Project has been following his mission right from its beginning on October 2, the birth anniversary of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, when he set off from the Rajghat Memorial at Delhi. Before leaving, he symbolically spun cotton with a hand-driven charkha, surrounded by a handful of supportive co-activists. Through his journey, Kumar remained connected with people, and routinely posted eye-opening reports, until he reached his destination—the entrance to the premises of a blighted central prison—at Taloja, close to Navi Mumbai, 52 days later.

His first overnight halt in his journey was at the indefinite sit-in by scores of terminated workers from the Maruti Suzuki car manufacturing plant, in the Manesar industrial borough of Gurgaon, which is still continuing 12 years later. In the ensuing days and weeks, Kumar traversed, all by himself, through the communally sensitive Mewat region, straddling south-east Haryana, the eastern tip of Rajasthan, next to Mathura, and went on to central Rajasthan, before heading southward, while mingling particularly with the Adivasi and Dalit indigenous populace all along, into eastern Gujarat. Meandering around, he cycled towards the Statue of Unity, and entered Maharashtra through the north-west of the state.

At various locations, Kumar made notes and shot videos on what the locals had to say about the government’s high-profile development projects and how they brought about devastation instead. He noted how these projects generated little hope for the people’s welfare, jobs, or any progress whatsoever—not even in the form of basic amenities such as toilets, village roads, primary schools, and healthcare. Meanwhile, the promise of allotting independent land to the individuals displaced by these projects remains unfulfilled. Land that by and large still belonged to feudal landlords, who diversified into money-spinning businesses, hardly spurring a regenerative economy. His posts and videos are worth a peek for those who would wish to comprehend the lives of whom we, the city-bred, call “the marginalised.”

The destination for the cycle march was a choice that emerged from a strong conviction. One of Kumar’s intentions was to prick the nation’s conscience over the languishing predicament, since early 2018, of “the 16 best minds of the country.” Of them, seven men and one woman still remain behind bars—the former in Taloja Central Jail and the latter in Byculla Women’s Jail. They are none other than those known, in many quarters by now, to have been falsely implicated in the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case: eminent authors, lawyers, professors, poets, song composers, theatre artistes, and researchers, most of whom doubled as activists, from different parts of the country.

Quality reams have been printed and gigabytes uploaded in the public domain about how, and for what nefarious purpose, the case was concocted under the previous Devendra Fadnavis government in Maharashtra. Credible forensic analyses and rational logic strongly suggest that the incriminating documents, purported as evidence, could only have been fabricated and implanted by state agencies, possibly assisted by non-state hackers, on the computers used by some of those arrested, none of whom has been granted bail as yet. Some of those “best minds” would soon complete seven crushing years in prison. One of them, Stan Swamy, known to have been a Jesuit priest most of his life, and also a beloved social activist and prolific writer, whose computer had apparently been compromised earliest of all—since 2014—could not survive his incarceration.

Kumar has been making valiant attempts to keep apprising people, every now and then, of many such disturbing facts, which have too short a shelf life in today’s mainstream media. His choice of the destination helped him veer conversations with the people he kept meeting, along his cycle tour and even after it, around the tragic misuse of the law and the prevailing criminal justice system.

In a quick interview with The Polis Project, at a Taloja studio, hours after reaching his destination, Kumar further explained that his choice of Delhi as the starting point of the cycle march was also similarly motivated. He wanted to draw the attention of people to the toxic targeting, wrongful arrests and prolonged incarceration without bail of a number of well-meaning, Delhi-based young leaders—mostly Muslim men and women, but also a few secular non-Muslims—in late 2019 and early 2020. Many of them played key roles in the popular protests that had gripped the country, against the anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act. The protests were forcibly withdrawn, in the face of a suddenly imposed lockdown, just when the early version of the COVID-19 virus struck India. But the Delhi pogrom, engineered around the time of the US president Donald Trump’s visit, became the smokescreen for many vindictive and communally tainted arrests. More than a dozen of those anti-CAA democratic agitators still languish in prisons, nearly five years down the line.

Kumar also drew the attention of his audiences to the more recent National Investigation Agency arrests in Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Chandigarh—with the agency still punching, allegedly beyond its calling. The NIA has fixed its scrutiny on another batch of activists—some of whom have been writing, practising legitimate professions, organising workers, or simply studying—accusing them of conspiring with a leading body of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist).

Deprivation in the name of counter-insurgency

Himanshu Kumar is no stranger to the state’s tactic of associating social activists with banned organisations. He faced the same situation while running his Vanvasi Chetna Ashram in Dantewada, the southernmost district to be carved out from Bastar. In July 2022, a Supreme Court bench of AM Khanwilkar and JB Pardiwala dismissed his 2009 petition seeking CBI investigations into the brutal massacres of innocent Adivasis in three Dantewada villages—Gachhanpalli, Gompad and Belpocha—on September 17 and October 1, 2009. The petition described the specific incidents in vivid details, and identified the perpetrators as Chhattisgarh Police, Central Reserve Police Force and its COBRA battalions, and Salwa Judum—a state-sponsored anti-Maoist militia, which was declared unconstitutional in 2011, and was therefore temporarily disbanded, only to be allegedly reconstituted as a District Reserve Guard. Yet, the Supreme Court bench not only dismissed the 2009 petition, but also slapped an “exemplary cost” of Rs 5,00,000—equivalent to over 6,000 in Euros or US dollars. The judgment, authored by Justice Pardiwala, took elaborate note of the current regime’s top prosecution counsel, Tushar Mehta’s allegations implying that, by levelling such grievous accusations against the state forces, Himanshu Kumar had been aiding and abetting the “heavily armed” Left-Wing Extremists (or Naxalites). The apex court stopped just short of initiating criminal proceedings on this count, though it made no bones about its displeasure against Kumar. A review petition against the judgement has also been dismissed.

While Kumar declines to pay the fine, he continues to circulate reports, until date, of incessant—in fact, escalating—alleged atrocities by the CRPF, COBRA, the Border Security Force, and the District Reserve Guard, all of which would seem to violate the fundamental right to life, liberty and livelihood, particularly in Bastar and its surrounding areas, in the name of counter-insurgency operations. He maintains that the military operations being advanced by the state are part of a corporate conspiracy to seize the forests and hills of central and eastern India, aimed at satisfying the rapacious greed of mining interests, both in India and abroad. The deprivation of the entire gamut of fundamental rights of the indigenous inhabitants are considered mere “collateral damage” in this reckless and violent endeavour.

According to Kumar, it was only incidental that just when he and his wife had succeeded in putting into place multiple welfare activities for the Gondi-speaking Adivasis of Dantewada, the government policies of “liberalisation, privatisation, globalisation” (LPG) came into full swing. “Chhattisgarh government had signed over 100 MoUs with investors” at the beginning of the current century, he observed. “Many of them were for mining projects in the Bastar area.” Kumar explained that this created a conflict because the indigenous people of Bastar posed a threat to the extraction of minerals from their land and forests. “So, the state constituted a private army, under the garb of Salwa Judum—which in Gondi meant, ‘a campaign to establish peace’—in order to pre-empt the inevitable peoples’ resistance.”

In the Nandini Sundar case, the Supreme Court ruled against the vigilante force, but the government simply inducted the Special Police Officers from Salwa Judum into an official District Reserve Guard, believed to now operate as a key component of the basic forces on the ground, under the unified command for central India, in military terms. “The SPOs, being Adivasis themselves, are now committing the same sort of atrocities as regularised personnel.” The basic military force of the state, till this day, thus seems to be composed of the former Salwa Judum personnel.

A couple of years ago, the Gondi Adivasis organised themselves as an independent collective called the Moolwasi Bachao Manch. Over the last three years, the Manch has been actively and effectively manifesting the demands and aspirations of Bastar’s local populace, to resist the aggressive state militarisation, with sheer bravado in the fast-shrinking democratic space. But towards the end of Kumar’s cycle march, this platform for peaceful struggle was also banned as an unlawful organisation under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act, 2005, accusing them of causing obstructions to the “developmental activities” of the state. Kumar has been inconsolably disturbed by recent reports of the wanton detentions, especially at unknown, undeclared centres, for indefinitely long periods, besides the illegal arrests and torture of the supporters of the Manch, particularly the younger women, and the bombing of fields of peasants around paramilitary camps. These are some of the many secrets that Kumar has tried to share with the indigenous people of western India, and beyond, in the course of his cycle tour.

Resilience against communal strife

When asked how he drew his courage, Kumar narrated a story of his elder uncle, Brahma Prakash Sharma, an advocate in whose honour a gate stands in the compound of Muzaffarnagar District Court, his native city in the state of Uttar Pradesh. Sharma, he recalled, had also been slapped a fine for alleged contempt of court in a petition flagging judicial corruption. “If my uncle was respected in Muzaffarnagar for his courage in taking up cudgels against judicial dishonesty, how can I be cowed down by such chicanery?” There was an uncompromising flourish in his challenge to the state.

Kumar’s father, Lakshmendra Prakash Sharma, who was also known as Prakash Bhai, was a trusted pupil of Gandhi himself, having studied in his first batch of Nayi Taleem. Prakash Bhai also participated in the 1942 Quit India movement, and the Bhoodan Aandolan launched by Sarvoday architect, Vinoba Bhave, in a bid to persuade landlords to voluntarily surrender their excess land to their landless peasants. Both parents followed Gandhi’s direction to the youth to perform social work in villages. So, they immersed themselves in serving villages in their home state. Kumar carried forward his parental legacy, settling deep inside present-day Chhattisgarh in 1992 with his newly-wedded wife.

Kumar attributes his existential choices mainly to his father and mother, but also to his great grandfather, Bihari Lal Sharma, a school headmaster. Among the select few educators of his time, the doyen of Kumar’s family actually authored a rare, Persian work of fiction, named, Ajeeb Khaab, a fantasy about a secular future. Kumar’s secularism manifests in his oration as well: his Hindi happens to be well enmeshed with its Persian component—he speaks perfect Hindostani, rather than the deliberately Sanskritised version of Hindi.

As he paddled his way into the Mewat region, Kumar was conscious of Gandhi’s role in winning over the predecessors of today’s Mewati Muslims. Faced with the dilemma of whether or not to cross over to Pakistan during the Partition, as many of their religious brethren from then East Punjab had been compelled to, Gandhi is said to have asked them, “Is God different in Pakistan than in India?” Ever since, the Mewati Muslims have generally embraced Gandhian initiatives, said Kumar.

Paramita Ghosh has discussed the syncretic culture of the Hindus and Meo Muslims of Mewat in a Hindustan Times article published in the wake of an incident from August 2016, when alleged cow vigilantes gangraped two Meo-Muslim girls in a Nuh village. Ghosh pointed out that it was PC Joshi, a leader of the then undivided Communist Party, who had introduced the leader of the Meo Muslims to Gandhi, implying Communist support in helping consolidate Meo Muslim bonds with India. The 2016 attack had “reopened old wounds,” she wrote, referring to the nostalgia over “common rituals” shared by Meo Hindus and Muslims in the not-too-distant past, and how it has endured multiple efforts to create fissures over the last century.

Kumar emphatically acknowledged the resilience of Meo collaboration across the religious divide, however much the fanatics may have damaged it. He referred to the infamous lynching of Pehlu Khan, a cattle trader from Mewat who was brutally assaulted to his death in April 2017 by cow-protection vigilantes, while speaking wryly of the divisive moves afoot to tear asunder the cultural fabric of the indigenous communities of Mewat. He remarked how the days he spent in the Mewat region—from Nuh in Haryana to Dausa in Rajasthan—made him realise that “the Muslims are as indigenous to the Mewat as the Hindu Jats, Gujjars and Meenas.” He found little difference in their way of living, customs and traditions. “Regardless of their religious denomination, the Mewatis have had the same agrarian and pastoral occupations, cooked in the same way, and commonly observed their festivals in mutual celebration.”

Since time immemorial, a traditional, 84-kos—a measure of distance varying from about two to three kilometres—circular pilgrimage, or parikrama, of Hindus, in Mewat has been serviced by the Muslims with equal gusto. To this day, sweet drinks and other consumables catered by Meo Muslims help the Hindu devotees complete the pilgrimage, offering a major source of energy and comfort. However, a much more strident form of the earlier Chaurasi Kos Parikrama, called the Brij Parikrama, replete with eardrum-shattering music and aggressive posturing, was launched a few years ago. In one of his many conversations with Kumar, Zafar Yaduvanshi, a Meo peasant leader from the national body of the farmers’ collective Samyukta Kisan Morcha, points how this newer version intentionally stokes the flames of anti-Muslim belligerence.

But has the fanatics’ alleged conspiracy and stridency inflicted any permanent damage so far?

Communal strife has been increasingly trumped up over the past decades in the mainstream media, noted Kumar, adding that on the ground, the scenario remains complex. He spoke of the failure of Hindu fanatics to inflame religious passions beyond a limit. Still, at a gathering of Sarvoday volunteers in Mumbai, on November 26, he admitted, in reply to a pointed question, that the situation could not be taken as lightly as Rahul Gandhi’s populist posturing with the use of phrases such as “Mohabbat ki Dukaan”—a Shop of Love. The way out of the effects of hate mongering would have to be found more diligently, he averred. Yaduvanshi, who was at the helm of the popular farmers’ movement, suggests that the only way to defeat the divisive forces was to consistently devise ways and means to struggle, in a symbiotic manner, for the rights of the toiling masses against the exploitative policies of the current regime.

In one of his posts, Kumar wrote that in Mewat, he “enjoyed the hospitality of homes, mosques, and madrassas” of Muslims. In the Meenawati region, it was the “homes of the Meena tribal community,” that drew him in, to “discuss and understand their lives,” as he headed into the heart of Rajasthan. The Gandhi Darshan Committee, the Satyagraha Committee, Congress workers, and others helped him organise anti-communal meetings and deliberations at various public places, and also helped him organise his food and rest, in addition to members of a Tribal Coordination Committee, who oversaw his tour from the start to finish.

Gujarat, meanwhile, lived up to the reputation of its authoritarian government, as sleuths constantly harassed the members of Kumar’s local support network, calling them up, not once or twice, but every few hours to ask about his whereabouts and the minute details of his activity. During a previous ride through the state, when the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah duo served as chief minister and home minister, he had been bodily transported along with his bicycle in a vehicle right into Maharashtra. The phone calls did not help ease the bitter memory of that past.

More importantly, Kumar found to his alarm a dispute over the figurative Statue of Unity, meant to commemorate the Congress “iron man” Vallabhai Patel. He exclaimed that “Adivasis are prevented from building huts, even toilets, under provisions of a Statue of Unity Act!” Land was reportedly taken over from Tadvi Adivasis, in the vicinity of the statue, after first persuading them to give up their animistic worship of nature, citing a false demographic threat to Hindus. Once they adopted the majority faith, their lands came to be acquired for restaurants, hotels and resorts, built by capitalists, to serve an elite clientele. It was only later that they realised that they were hoodwinked into subservience according to a game-plan of the ruling party, and its ideo-political objectives. Kumar wondered if the constitution of Bharat Adivasi Party could be a reaction to precisely such Hindutva realpolitik. “The BAP now has representation in Parliament and the Assembly,” he pointed out with glee.

Kumar lost no opportunity to engage with the Hindu youth too—and he met quite a few as he pedalled along—taking pains to explain to them how they were actually being used for nefarious ends. “By provoking them to be aggressive at the time of Ram Navami processions, for instance, to hurl abuses at, or physically attacking, the minorities for no sane reason, a substantial section of the youth was being criminalised,” he argued. “In the long run, even if the powers-that-be may derive political gains and stay in power for a few more years than they deserved, it would disunite the country through and through.” Forces opposed to the real criminalisation have been increasingly subjected to fake criminalisation under repressive Acts and a sectarian police machinery, with the judiciary not helping, the Gandhian maintained.

Presenting details of his halts along the course of his paddling experiment, Kumar specified, in one of his posts, the secret of his high spirits, and why he could get by without any hurdle, “Among my friends are people from tribal, Muslim, Dalit, Gandhian, leftist and Congress backgrounds, along with those involved in social movements, including farmers, labourers and women’s movements.” With such a varied array of support, he hopes to find the social, political and economic way out of the problems facing the country under the current regime.

“Only twice did my cycle need a patching up of punctures,” Kumar said, as he retold stories of how his tyres rolled across rivers and mountains, along both fertile and arid zones, farms, woods and mangroves, puffing through the dusty Aravallis and exerting up the granite slopes of the northern Western Ghats. All along the journey, he surveyed the landscape, interrupted by the wounds of devastation caused by a profusion of development projects, destined to serve the rich and privileged, while severely impairing the poor and underprivileged inhabitants of, and around, a substantial part of the acquired land and forests.

Kumar did not fail to take notice of the endless struggles, individual and collective, of virtually every section of the toiling masses, for their basic right to life and livelihood, in pursuit of the mirage of equal opportunities, and for their freedom of belief and dissent. That, in fact, was his main conclusion, though he seemed curious about the different forms of struggles being adopted across the country. The state, nonetheless, remained impervious, I retorted, in a private conversation with him. He lost no time in correcting me, “The ruling BJP, in all the states that it rules today, pounces upon the slightest opportunity to create rifts and conflicts out of non-issues, in a desperate bid to divert the toiling peoples’ attention from the basic issues that concern their lives and livelihoods: the lack of jobs, the spiralling prices, and no real development in terms of amenities for themselves.” This, he suggested, was a demonstration of an endemic weakness that has gripped the state; an insecure state could not bode well for any positive development.

Many such conversations appeared to have been generated in the wake of the cycle march, in the context of the mutually shared desire of the many activists and social scientists, who continue to interact with him, with an eagerness to help catalyse a process of positive change.

An unmistakable takeaway at the end of the march was, as Kumar put it, “It has strengthened my resolve, my physical condition, and also my confidence.” For a chronic patient of Myasthenia Gravis, a troublesome neuromuscular disorder, the solo 2,000-kilometre-long cycle march was nothing short of what his physician called it—a miracle.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.