Feminichi Fathima and Victoria Interrogate the Interiority of Women’s Lives and Celebrate Seemingly Small Victories

Two Malayalam films that world premiered at the 29th International Film Festival of Kerala in December 2024 share DNA despite employing different milieu and techniques.

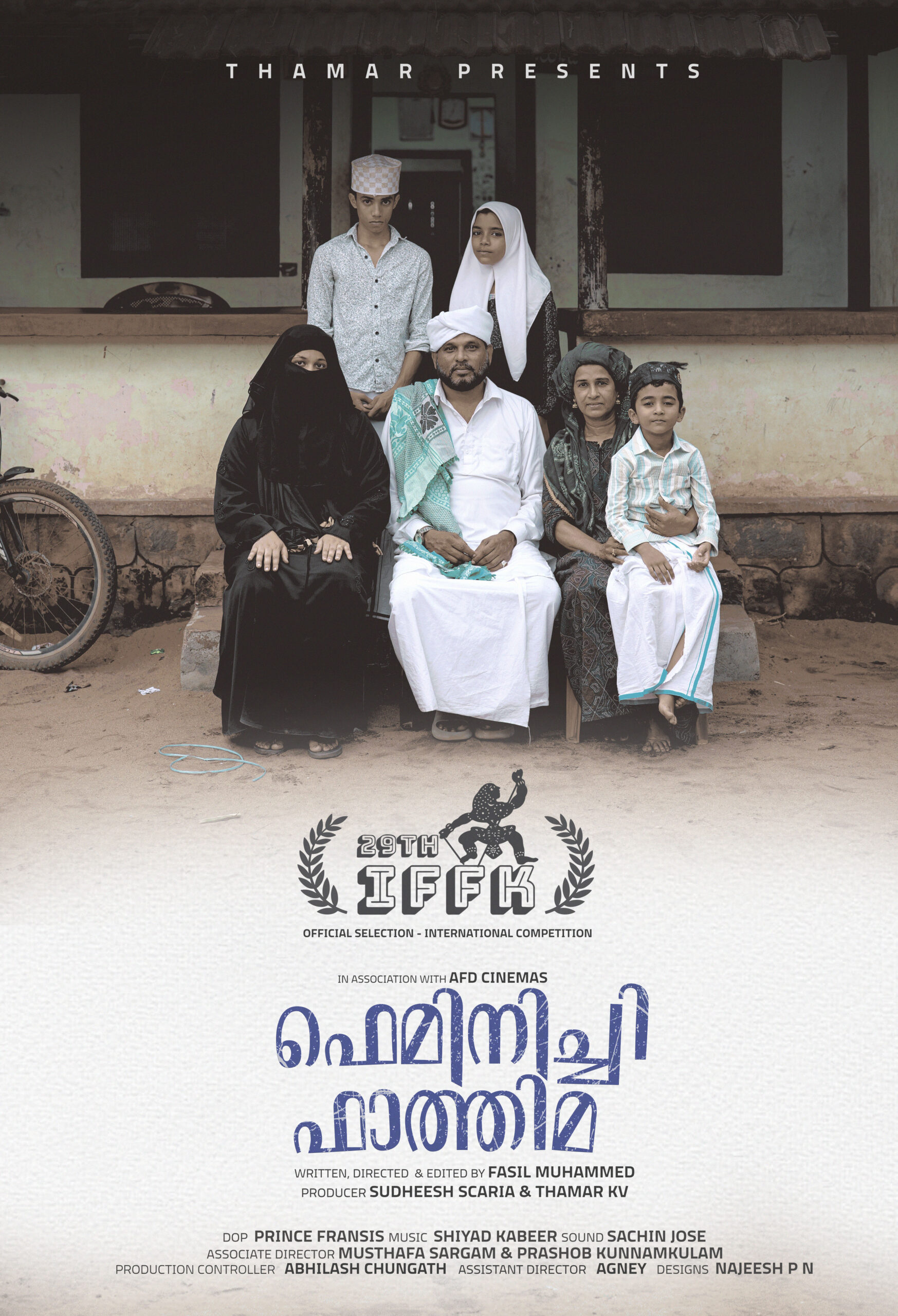

Fasil Muhammed’s Feminichi Fathima (also screened at the 14th Indian Film Festival of Bhubaneswar) is about the eponymous Muslim housewife in Ponnani in Malappuram and possesses a day-in-the-life narrative. Sivaranjini’s Victoria designs a single day as a series of single takes in the life of Victoria, a beautician at a parlor in Angamaly who is juggling a characteristically busy day at the office and a tenuous period in her personal life.

The two films have little in common in terms of setting and visual grammar, but they share philosophies and wrestle with the politics of survival and existence. They focus on women’s labor, the physical strain on their bodies, and the casually developing solidarity with the women around them.

In an interview that is now five years old, writer, director, and lyricist Muhsin Parari said that the representation of Muslim women in Malayalam cinema is either poor, heavy-handed, or stereotypical. “A heroine who portrays a Muslim character wears a burkha, jumps over walls, and sings rock music for liberation,” he said. “Or when she goes out for work, the family runs behind her and hands her a hijab.”

According to Parari, there is no attempt to go deep into their culture, thinking, or aesthetics.

Muhammed’s debut film Feminichi Fathima seeks to bridge this gap, depicting a particular facet of Muslim life in Malappuram (the setting for some of Parari’s films as well) with nuance and complexity. It follows Fathima (Shamla Hamza), who lives with her husband—an ustad in the local madrassa—her mother-in-law, and three children.

Fathima’s home ticks all the boxes for a typical den of patriarchy where the wife submits herself to endless household work with no returns—not in the form of pay, not in the form of love or compassion. “Fathima…Faaathima” is her husband’s almost monosyllabic call that is stable throughout the day. He calls her to switch on the fan in his room or to gesture that there is no drinking water in the jug. Or to get him his slippers and shawl when he steps out.

The first thirty to forty minutes of Feminichi Fathima depict the titular protagonist’s regular day. She wakes the children up, cooks, cleans, serves breakfast, prepares the kids for school, and drops the youngest at play school. When they leave the house, she cleans, mops, and washes clothes by hand.

Fathima’s troubles begin to dawn on her when her elder son wets the bed, and she must dry and clean the mattress. In a series of unfortunate and unjust events, the mattress becomes a symbol for her husband. She begins to sleep without one, and her endless work and chronic back pain make her determined to acquire a mattress, old or new.

Meanwhile, Victoria begins with the eponymous character (Meenakshi Jayan) on a bus sitting next to an elderly woman. The woman talks about a snake in her yard, but Victoria’s mind is elsewhere. They get off the bus and walk across the road when the woman thrusts a rooster—for sacrifice at church later—in Victoria’s hands to safeguard and says she’ll take it from her later in the day.

Victoria walks into the beauty parlor where she works, with a signboard that says no men allowed. From here, Sivaranjini’s film is a chamber drama composed of a series of tasteful unbroken shots.

Victoria’s parents have learned about her relationship with a Hindu man, an Uber driver. Things are heating up at home, her love life, and her workplace. She wants to elope, but her boyfriend dismisses her concerns.

Three new customers walk in when only Victoria is on the job. One of them, Deepa (Steeja Mary), is a ferocious raconteur, bouncing from one story to another. As if to complement her, the camera (cinematography by Anand Ravi) moves with her and her tall tales. Another customer joins in, a construction worker who talks about ogling Deepa’s father-in-law when he was young and how their respective caste statuses meant they always kept a cautious distance.

When the disquiet and jitters of the film’s form reach a fever pitch, Sivaranjini brings in three schoolgirls who break into a song; everyone in the parlor suddenly pauses to enjoy a peaceful moment. Amidst all this, Victoria continues working, moving from one woman to another, her hands busy over hair, henna, eyebrows, and different apparatuses with different customers.

Both Fathima and Victoria have moments where they express how tired they really are as they endlessly perform, laboring away at their chores one after another. For Fathima, it is at home. For Victoria, work is an escape from her tumultuous personal life. Sivaranjini uses the claustrophobic confines of a small beauty parlor to conjure an abode for Victoria away from a community with no intention to help her. A handheld camera brings out the anxieties of Victoria’s life, with Sivaranjini’s innovative use of small spaces, blocking, and mirrors allowing her to focus on an increasingly crowded parlor.

The parlor and the restroom within it become Victoria’s cocoon. In the restroom, she is vulnerable and cries to her boyfriend on the phone. When she is out, she has her game face on and treats the customers with love and respect, playing the perfect saleswoman, and attracting them to different services.

There is a ghost of Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman in both films, especially her 1975 masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. This influence is more apparent in Feminichi Fathima, with its focus on reproductive labor. There is an unspoken violence to the performance of caregiving and housework, which manifests as the physical and emotional breakdown of the individual.

It is the mundanity of Fathima’s labor and caregiving for no return that Victoria tries to avoid, a hope that shatters when her boyfriend’s words suggest she might be in for a life like that. In Jeo Baby’s The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), the filmmaking takes on an anxious temperament; cooking and cleaning transform into brutal labor shot with the kind of film grammar we associate with physical violence and gore.

In Feminichi Fathima, Muhammed chooses a more Akerman-like approach. The pretense that care and love are simple acts slowly disintegrates as we see Fathima walking long distances carrying a hand-me-down replacement mattress or eating her lunch alone at the same place where the rest of her family members throw the dishes. Muhammed’s use of public and private spaces impresses societal expectations about women and housework while unveiling their invisibilized labor.

The other ubiquitous storytelling contraption in Feminichi Fathima and Victoria is technology. By sheer luck, Fathima gets her husband’s old smartphone while he takes the new one her brother brings for her from Dubai. From that rickety old cot, when she cannot sleep due to back pain, she learns what is happening at her children’s school through WhatsApp.

When the scrap dealer helps Fathima’s mother-in-law top up her SIM card, she develops a renewed interest in learning beyond her immediate chores. Her neighbor Soora (Viji Viswanath) introduces her to digital payments, and one of Muhammed’s fresher decisions is to not show Fathima as someone moping about her lack of knowledge in these areas. She instead finds a new purpose, fascinated by the larger world out there.

Alternatively, while technology isn’t part of the fabric of Victoria, it is stitched into its grammar. We see no man except for Victoria’s boyfriend Prajeesh through the phone screen, his words reducing him to a man smaller than the figurine in the video call. Likewise, Victoria’s text messages with her mother remove all exposition required for the film.

The conversations between the women in the parlor and between Fathima and the women around her display a real solidarity among them. Fathima’s neighbor Soora is both her chief motivator and one who commands her to stand up to her family. Her friendship with Soora and the neighborhood women, including the scrap dealer, her encounter with technology and its power, and her work in the kitchen rewarded with payment brings out the latent feminism inside her.

The alchemy of experiences in a day—from the conversations with her customers to a breakdown in front of an old friend—gives Victoria the freedom to make bold decisions.

Victoria and her friend joke about the rooster’s life—they wander all day, get food, and sleep around with the ladies. Fathima’s husband is faithful to her, but he does live like that rooster, a life where everything is presented to him on a platter by Fathima, the doer.

There is another line in Victoria that is beautiful for its simplicity and brutal as a truism. Victoria’s pregnant friend tells her about her husband. “He is a decent guy,” she says, “but not a caregiver. I must ask for everything I want”—a devastating indictment of even the supposed “nice guys.” Reproductive labor, housework, and caregiving are so gendered that it is not expected from even those who gain the tag “decent.” Fathima’s husband is far from a caregiver, and Victoria’s boyfriend turns out to be worse.

As Parari mentions in the interview, feminism in Indian cinema has long been represented with an upper-class gaze. Popular Tamil, Telugu, and Hindi films are often satisfied with imagery where women replace men in traditional roles. They seldom interrogate the interiority of women’s lives or give due weight to small victories.

In Feminichi Fathima and Victoria, the protagonists’ positions are complicated by gender, religion, caste, and class. For Fathima and Victoria, what look like small victories are life-altering occasions.

Related Posts

Feminichi Fathima and Victoria Interrogate the Interiority of Women’s Lives and Celebrate Seemingly Small Victories

Two Malayalam films that world premiered at the 29th International Film Festival of Kerala in December 2024 share DNA despite employing different milieu and techniques.

Fasil Muhammed’s Feminichi Fathima (also screened at the 14th Indian Film Festival of Bhubaneswar) is about the eponymous Muslim housewife in Ponnani in Malappuram and possesses a day-in-the-life narrative. Sivaranjini’s Victoria designs a single day as a series of single takes in the life of Victoria, a beautician at a parlor in Angamaly who is juggling a characteristically busy day at the office and a tenuous period in her personal life.

The two films have little in common in terms of setting and visual grammar, but they share philosophies and wrestle with the politics of survival and existence. They focus on women’s labor, the physical strain on their bodies, and the casually developing solidarity with the women around them.

In an interview that is now five years old, writer, director, and lyricist Muhsin Parari said that the representation of Muslim women in Malayalam cinema is either poor, heavy-handed, or stereotypical. “A heroine who portrays a Muslim character wears a burkha, jumps over walls, and sings rock music for liberation,” he said. “Or when she goes out for work, the family runs behind her and hands her a hijab.”

According to Parari, there is no attempt to go deep into their culture, thinking, or aesthetics.

Muhammed’s debut film Feminichi Fathima seeks to bridge this gap, depicting a particular facet of Muslim life in Malappuram (the setting for some of Parari’s films as well) with nuance and complexity. It follows Fathima (Shamla Hamza), who lives with her husband—an ustad in the local madrassa—her mother-in-law, and three children.

Fathima’s home ticks all the boxes for a typical den of patriarchy where the wife submits herself to endless household work with no returns—not in the form of pay, not in the form of love or compassion. “Fathima…Faaathima” is her husband’s almost monosyllabic call that is stable throughout the day. He calls her to switch on the fan in his room or to gesture that there is no drinking water in the jug. Or to get him his slippers and shawl when he steps out.

The first thirty to forty minutes of Feminichi Fathima depict the titular protagonist’s regular day. She wakes the children up, cooks, cleans, serves breakfast, prepares the kids for school, and drops the youngest at play school. When they leave the house, she cleans, mops, and washes clothes by hand.

Fathima’s troubles begin to dawn on her when her elder son wets the bed, and she must dry and clean the mattress. In a series of unfortunate and unjust events, the mattress becomes a symbol for her husband. She begins to sleep without one, and her endless work and chronic back pain make her determined to acquire a mattress, old or new.

Meanwhile, Victoria begins with the eponymous character (Meenakshi Jayan) on a bus sitting next to an elderly woman. The woman talks about a snake in her yard, but Victoria’s mind is elsewhere. They get off the bus and walk across the road when the woman thrusts a rooster—for sacrifice at church later—in Victoria’s hands to safeguard and says she’ll take it from her later in the day.

Victoria walks into the beauty parlor where she works, with a signboard that says no men allowed. From here, Sivaranjini’s film is a chamber drama composed of a series of tasteful unbroken shots.

Victoria’s parents have learned about her relationship with a Hindu man, an Uber driver. Things are heating up at home, her love life, and her workplace. She wants to elope, but her boyfriend dismisses her concerns.

Three new customers walk in when only Victoria is on the job. One of them, Deepa (Steeja Mary), is a ferocious raconteur, bouncing from one story to another. As if to complement her, the camera (cinematography by Anand Ravi) moves with her and her tall tales. Another customer joins in, a construction worker who talks about ogling Deepa’s father-in-law when he was young and how their respective caste statuses meant they always kept a cautious distance.

When the disquiet and jitters of the film’s form reach a fever pitch, Sivaranjini brings in three schoolgirls who break into a song; everyone in the parlor suddenly pauses to enjoy a peaceful moment. Amidst all this, Victoria continues working, moving from one woman to another, her hands busy over hair, henna, eyebrows, and different apparatuses with different customers.

Both Fathima and Victoria have moments where they express how tired they really are as they endlessly perform, laboring away at their chores one after another. For Fathima, it is at home. For Victoria, work is an escape from her tumultuous personal life. Sivaranjini uses the claustrophobic confines of a small beauty parlor to conjure an abode for Victoria away from a community with no intention to help her. A handheld camera brings out the anxieties of Victoria’s life, with Sivaranjini’s innovative use of small spaces, blocking, and mirrors allowing her to focus on an increasingly crowded parlor.

The parlor and the restroom within it become Victoria’s cocoon. In the restroom, she is vulnerable and cries to her boyfriend on the phone. When she is out, she has her game face on and treats the customers with love and respect, playing the perfect saleswoman, and attracting them to different services.

There is a ghost of Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman in both films, especially her 1975 masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. This influence is more apparent in Feminichi Fathima, with its focus on reproductive labor. There is an unspoken violence to the performance of caregiving and housework, which manifests as the physical and emotional breakdown of the individual.

It is the mundanity of Fathima’s labor and caregiving for no return that Victoria tries to avoid, a hope that shatters when her boyfriend’s words suggest she might be in for a life like that. In Jeo Baby’s The Great Indian Kitchen (2021), the filmmaking takes on an anxious temperament; cooking and cleaning transform into brutal labor shot with the kind of film grammar we associate with physical violence and gore.

In Feminichi Fathima, Muhammed chooses a more Akerman-like approach. The pretense that care and love are simple acts slowly disintegrates as we see Fathima walking long distances carrying a hand-me-down replacement mattress or eating her lunch alone at the same place where the rest of her family members throw the dishes. Muhammed’s use of public and private spaces impresses societal expectations about women and housework while unveiling their invisibilized labor.

The other ubiquitous storytelling contraption in Feminichi Fathima and Victoria is technology. By sheer luck, Fathima gets her husband’s old smartphone while he takes the new one her brother brings for her from Dubai. From that rickety old cot, when she cannot sleep due to back pain, she learns what is happening at her children’s school through WhatsApp.

When the scrap dealer helps Fathima’s mother-in-law top up her SIM card, she develops a renewed interest in learning beyond her immediate chores. Her neighbor Soora (Viji Viswanath) introduces her to digital payments, and one of Muhammed’s fresher decisions is to not show Fathima as someone moping about her lack of knowledge in these areas. She instead finds a new purpose, fascinated by the larger world out there.

Alternatively, while technology isn’t part of the fabric of Victoria, it is stitched into its grammar. We see no man except for Victoria’s boyfriend Prajeesh through the phone screen, his words reducing him to a man smaller than the figurine in the video call. Likewise, Victoria’s text messages with her mother remove all exposition required for the film.

The conversations between the women in the parlor and between Fathima and the women around her display a real solidarity among them. Fathima’s neighbor Soora is both her chief motivator and one who commands her to stand up to her family. Her friendship with Soora and the neighborhood women, including the scrap dealer, her encounter with technology and its power, and her work in the kitchen rewarded with payment brings out the latent feminism inside her.

The alchemy of experiences in a day—from the conversations with her customers to a breakdown in front of an old friend—gives Victoria the freedom to make bold decisions.

Victoria and her friend joke about the rooster’s life—they wander all day, get food, and sleep around with the ladies. Fathima’s husband is faithful to her, but he does live like that rooster, a life where everything is presented to him on a platter by Fathima, the doer.

There is another line in Victoria that is beautiful for its simplicity and brutal as a truism. Victoria’s pregnant friend tells her about her husband. “He is a decent guy,” she says, “but not a caregiver. I must ask for everything I want”—a devastating indictment of even the supposed “nice guys.” Reproductive labor, housework, and caregiving are so gendered that it is not expected from even those who gain the tag “decent.” Fathima’s husband is far from a caregiver, and Victoria’s boyfriend turns out to be worse.

As Parari mentions in the interview, feminism in Indian cinema has long been represented with an upper-class gaze. Popular Tamil, Telugu, and Hindi films are often satisfied with imagery where women replace men in traditional roles. They seldom interrogate the interiority of women’s lives or give due weight to small victories.

In Feminichi Fathima and Victoria, the protagonists’ positions are complicated by gender, religion, caste, and class. For Fathima and Victoria, what look like small victories are life-altering occasions.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.