In 2024, a group of researchers and activists set out on a challenging mission: to map out instances of hate speech and blasphemy-related violence across Pakistan. A member of the research team, who wished to remain anonymous, said their work focused on documenting posters and slogans on blasphemy and not talking to people. But when they spoke to people, they had to pretend that they supported the blasphemy laws. “I was in a shop, and took a picture of a poster without consent,” he recalled one incident. The poster called for attacking or killing anyone who “disrespected” Prophet Muhammad. “The shop owner grabbed me and asked: what are you doing? So, I had to tell him I thought this [the poster] was cool.”

In another incident of confrontation during field documentation, he had to misrepresent his views on the persecuted minority Ahmadis to ensure his own safety. “I took a picture in a mosque, and then the imam called me and asked what I was doing. I told him the Ahmadi community is against Islam, and after that, all the people around me turned 180 degrees in their attitude. They even gave me many of their pamphlets,” he narrated.

The concept of blasphemy—or Gustakhi, as it is called in Urdu—is deeply entrenched within the Muslim-Pakistani identity and within the Pakistani society as a whole. The laws only bolster this aspect.

Pakistan’s laws on “offences relating to religion”, commonly known as “blasphemy laws”, lay down an array of crimes and their punishment—from “defiling” the Quran, to “deliberate and malicious” acts outraging religious sentiment and using derogatory remarks in respect of the Prophet Muhammad. The vague definition of desecration in the laws creates a significant challenge: even discussing or critiquing the laws could potentially be interpreted as blasphemy. This ambiguity has emboldened many citizens to take enforcement into their own hands, resulting in increased vigilante violence against both alleged blasphemers and critics of the law itself. The situation is further exacerbated by law enforcement’s frequent reluctance to intervene in blasphemy-related incidents, making it nearly impossible to maintain public order in such cases.

The laws, which comprise multiple sections of the penal code, create an atmosphere of fear in the country. According to the US Department of State, as well as non-governmental reports over the years, the law disproportionately affects religious minorities, and its provisions are used as pretext for mob-led violence against the accused. Although there is a lack of official data on blasphemy-related cases and violence, due to many cases not being registered with the police, the available sources indicate that cases only continue to rise, and the laws are used to carry out political and social vendetta.

The researchers mapping out blasphemy violence last year were working with Engage Pakistan, a nonprofit advocacy group working on blasphemy laws. Their research reveals how the country’s blasphemy laws cause an increase in violence and fear that do not reach the courtrooms. Through their documentation of hate speech and inflammatory posters across the country, the researchers observed how blasphemy accusations have become tools for social control and persecution. The US Commission on International Religious Freedom cites that at least 53 people were in custody under blasphemy charges across Pakistan as of 2023. However, the report shows that these numbers barely scratch the surface of how the law shapes social dynamics and enables persecution, particularly of religious minorities, through the constant threat of accusation.

Regardless of whether the matter is in court or outside, the fear of accusation remains the same. Lazar Allah Rakha, a Christian human-rights lawyer who has represented many of those accused of blasphemy, points out that in a lot of these cases, issues around blasphemy accusations and violence become more dangerous for the accused when they come to court because the case then comes into the public eye. “Please sort these issues out before bringing them to court. The more open it is, the more danger it puts people in,” Allah Rakha said.

Understanding the blasphemy laws

The colonial era blasphemy laws, retained by Pakistan’s Penal Code, were further strengthened in the 1980s under General Zia-ul-Haq’s military government. Eventually, blasphemy was made punishable by death in 1986. Section 295-C was introduced into the Penal Code, which states: “Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine.” Clauses under Section 295 also comprises punishments for desecration of the Quran and other offences deemed insulting to Islam.

While an increased use of the law is often attributed to Haq, his predecessor Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto also made contributions. In 1974, under Bhutto, Pakistan’s parliament unanimously passed a constitutional amendment declaring the Ahmadiyya community as non-Muslim. This move was largely in response to widespread riots and protests that demanded such a declaration. The amendment altered Article 260 of the Constitution, officially classifying Ahmadis as non-Muslims. This legislative change not only marginalised the Ahmadiyya community but also laid the groundwork for more stringent blasphemy laws in the country.

After these past leaders, both civilian leaders and military rulers have kept the laws alive. Critics often ignore the ways more recent political leaders have also endorsed the law. Khadim Rizvi, founder of the hardliner Tehreek E Labbaik Pakistan, and even the populist leader Imran Khan, have both endorsed the law and backed efforts to protect it. On the other hand, activists who have been calling for a removal—or at least amendment—of the law have long been disregarded. In fact, attempts made in 2010 to amend the law were withdrawn due to pressures from religious groups and death threats to the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP) senator Sherry Rehman, who had proposed the amendments.

Qibla Ayaz, a former chairperson of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), which is the country’s top religious advisory body, told the BBC in 2019 that the government was not ready to change the blasphemy law in fear of backlash. Further, his suggestions for penalties over misuse of the law were not implemented.

Critics of the law also note its misuse in persecution of religious minorities. The advocate Allah Rakha pointed out that a law is meant to ensure equality through equal rights, but the blasphemy law does not do that. “We see if one citizen’s holy book is desecrated or disrespected, its punishment is life sentence, but for another citizen’s book, there is no punishment,” he said. “People can have different religions. The state does not have a religion, but we have started considering the state as a person, and not an institution of governance.”

In late January 2025, four people were convicted for committing blasphemy online. The trial court sentenced the convicts to death under Section 295-C, life imprisonment under Section 295-B of the penal code, and ten years of imprisonment along with a fine of Rs 100,000 each under Section 295-A. Under Section 298-A, the convicts were sentenced to three years of imprisonment and fined Rs 100,000 each. Under the Prevention of Electronic Crime Act (PECA) Act 2016, the convicts were sentenced to seven years of imprisonment and fined Rs 100,000 each.

International organisations have estimated that up till 2022, 40 people had been tried for blasphemy in Pakistan, but no executions took place. On the other hand, at least 89 vigilante killings were recorded in relation to blasphemy accusations between 1947 and 2021. While court cases and deaths in relation to this issue are the most obvious way to record blasphemy violence, such data does not cover the whole issue because the everyday violence, accusations and fear that permeate through society cannot be counted as easily.

A cornered judiciary

The blasphemy laws resurfaced as a central issue in August last year as religious ire led the judiciary to revisit the Mubarak Sani case. Sani, who belongs to the minority Ahmadi community, was acquitted in February 2024 after having been accused under the Punjab Holy Quran (Printing and Recording) Amendment Act 2021, which criminalises the unauthorised printing, recording, and distribution of the Holy Quran and its extracts, both physically and digitally. The Supreme Court bench led by the chief justice decided that Sani had distributed the Ahmadi religious text before the act had become criminalised, leading to his acquittal, and noted that he had already served 13 months in prison. The maximum punishment for the offence is six months.

Sani was also charged under some blasphemy laws—Sections 295-B and 298-C—which criminalise the desecration of the Quran and prohibit members of the Ahmadi community from identifying as Muslims or preaching their faith. However, the Supreme Court noted that the First Information Report (FIR) and police investigation contained no evidence to support these charges.

The approximately 500,000-strong Ahmadi or Ahmadiyya community in Pakistan is a religious minority that considers itself Muslim but the blasphemy laws bar them from referring to themselves as such, and from practising aspects of their faith. While all minority communities in Pakistan face some sort of discrimination, Ahmadis particularly come under threat because many Sunni groups see them as changing Islam, which they perceive to be a threat.

The constitution has branded them non-Muslims since 1974, and a 1984 law forbids them from even claiming their faith as Islamic. Unlike in other countries, they cannot refer to their places of worship as mosques, make the call to prayer, or travel on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. The blasphemy laws mainly target Ahmadis but are also used against other minorities in an effort to “preserve Islam”.

Sani’s acquittal in February 2024 stirred up controversy. In July, the Supreme Court revisited the case after calls for review by religious political parties like Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam – Fazl (JUI-F), Jamaat-e-Islami, and Tehreek E Labbaik Pakistan, and a petition filed by the Punjab government. It accepted the review petition and said Ahmadis in Pakistan could practice their faith privately, but not publicly use Muslim terms or identify as Muslims. The court argued that the offences listed under sections 298 A, B and C—which deal with offences against religious sentiments—only applied when done publicly.

The judgment prompted fresh objections and protests near the Supreme Court premises by parties who believed that Ahmadis should not be allowed to practice their beliefs. The Supreme Court then held a second “review”—although it was termed a “correction”—in August. The correction led to the redaction of certain paragraphs from the verdict, such as those stating Ahmadis were allowed to privately practice their religion. Article 20 of Pakistan’s Constitution confers citizens with the right to profess and practice their religions. But the court redacted the observation from the judgment, noting that it went against laws that banned disrespect of the Quran.

The top court also issued a direction that the expunged paragraphs would not be used as precedent in the future and instructed the trial court hearing the Mubarak Sani case to not be influenced by the two prior judgments.

Sani’s case is one of many in Pakistan where Ahmadis have been accused of disrespecting Prophet Muhammad or the Quran, and faced protracted legal trials, and even mob violence. What should have been an easily wrapped-up case, ended up going through two reviews under pressure from religious groups. Noting the significance of this development, Khalid Ranjha, a senior lawyer and a former federal minister for law and justice, told voicepk.net that the Supreme Court had never before heard a matter after the review petition was already decided. He also warned that this could enable the government to appeal to overturn other judgements in the future.

Since the Supreme Court revisited the case, concerns have risen around how religious and political pressures are influencing the judiciary and weakening its independence. Many activists and advocates of free speech have criticised the increasing use of the blasphemy laws and the control these give right-wing religious leaders over the Pakistani society as a whole. The increased control and pressure have led to fear among minority groups in particular. Amir Mehmood, a spokesperson for the Ahmadi community in Pakistan, points out that almost no lawyers want to represent such cases anymore because they fear the consequences that come with the association. But it is not just minorities who are at risk; Mehmood said, “Ab rahi nahin koi baat khatre ki, ab sab ko sabhi se khatra hain (Now there is no issue of danger as everyone is at risk from everyone).”

In September, his words were proven true in the case of Mufti Tariq Masood, who was forced to spend several days apologising for saying that the Quran appeared to have grammatical mistakes. Despite clarifying that he was talking about perceptions, Masood, a prominent cleric and religious leader, has been getting severe threats and has even released a video saying he feared something would happen to him.

It’s a story Pakistan has seen time and again, each time with similar criticisms, reporting, and the absence of any subsequent change.

Propagation of hate and intolerance

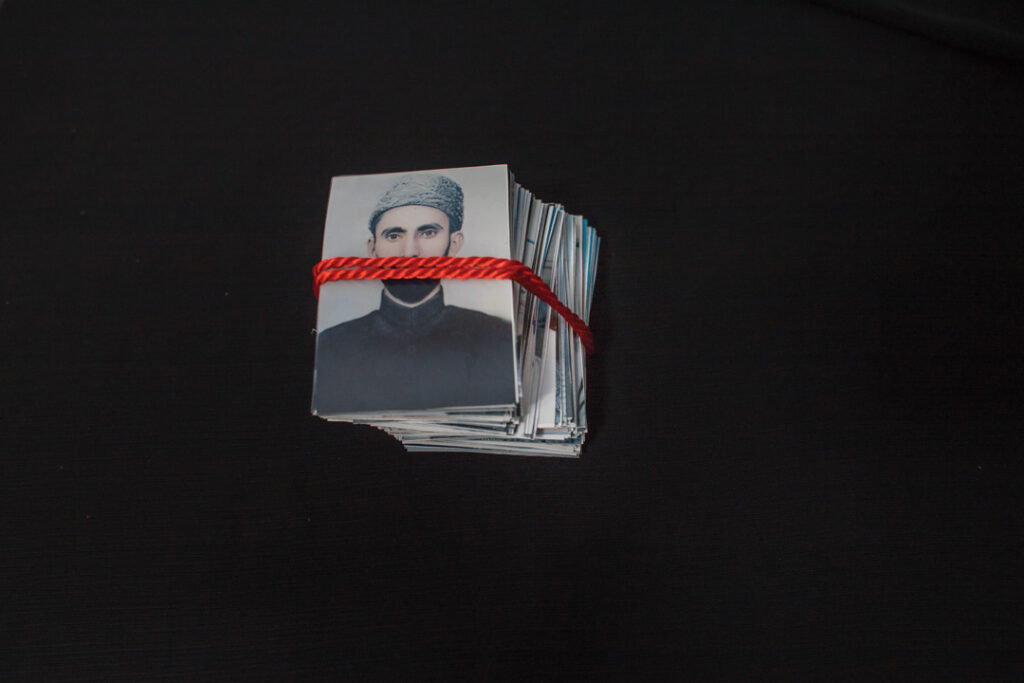

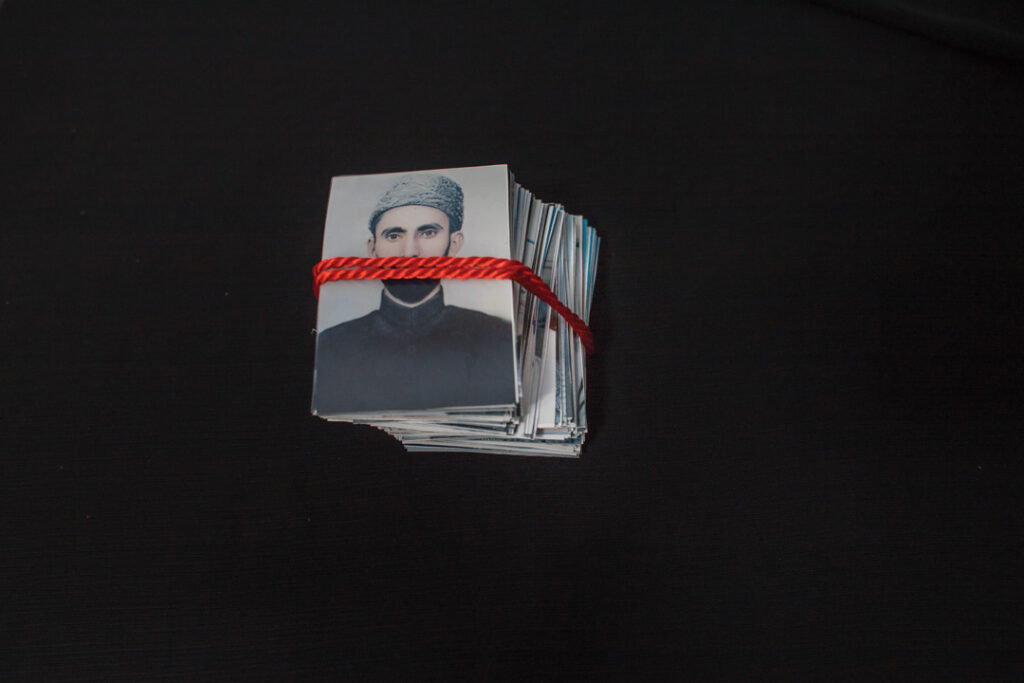

When Arafat Mazhar, the director of Engage Pakistan, a non-profit organisation that aims to reform the country’s blasphemy law, and his team decided to investigate hate speech and blasphemy-related violence in 2024, they sought to highlight its pervasiveness and normalisation in Pakistani society. The researchers conducted their work across working class areas in Punjab over the last year.

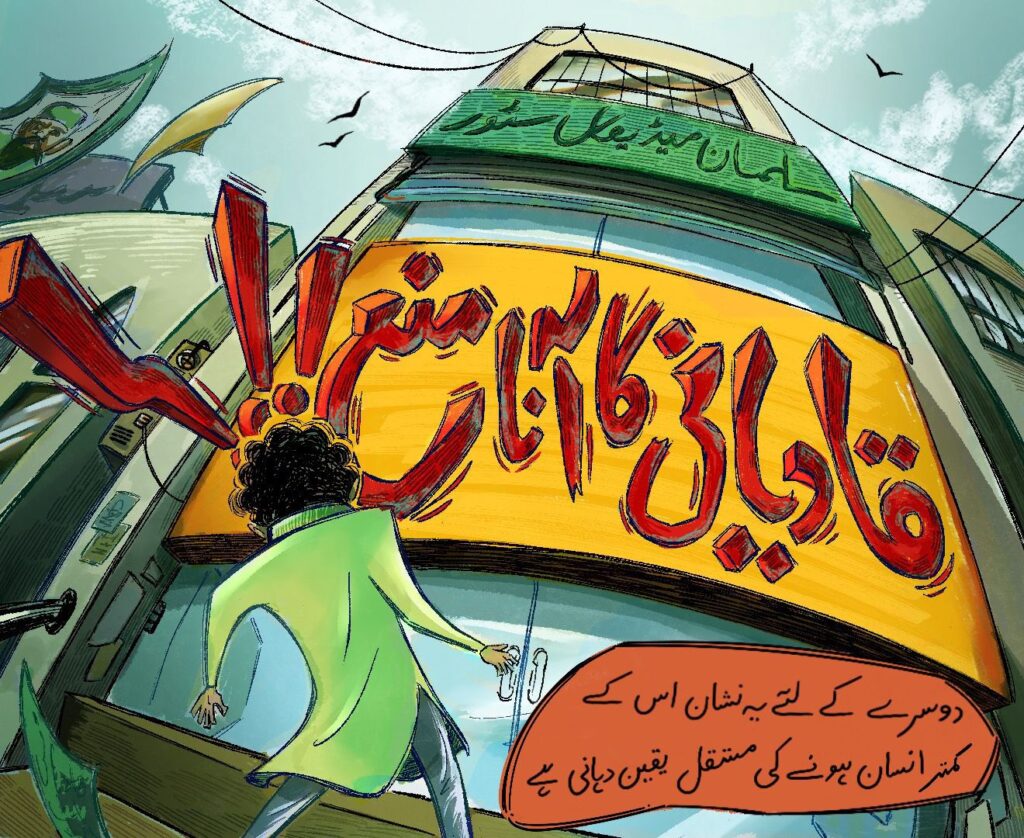

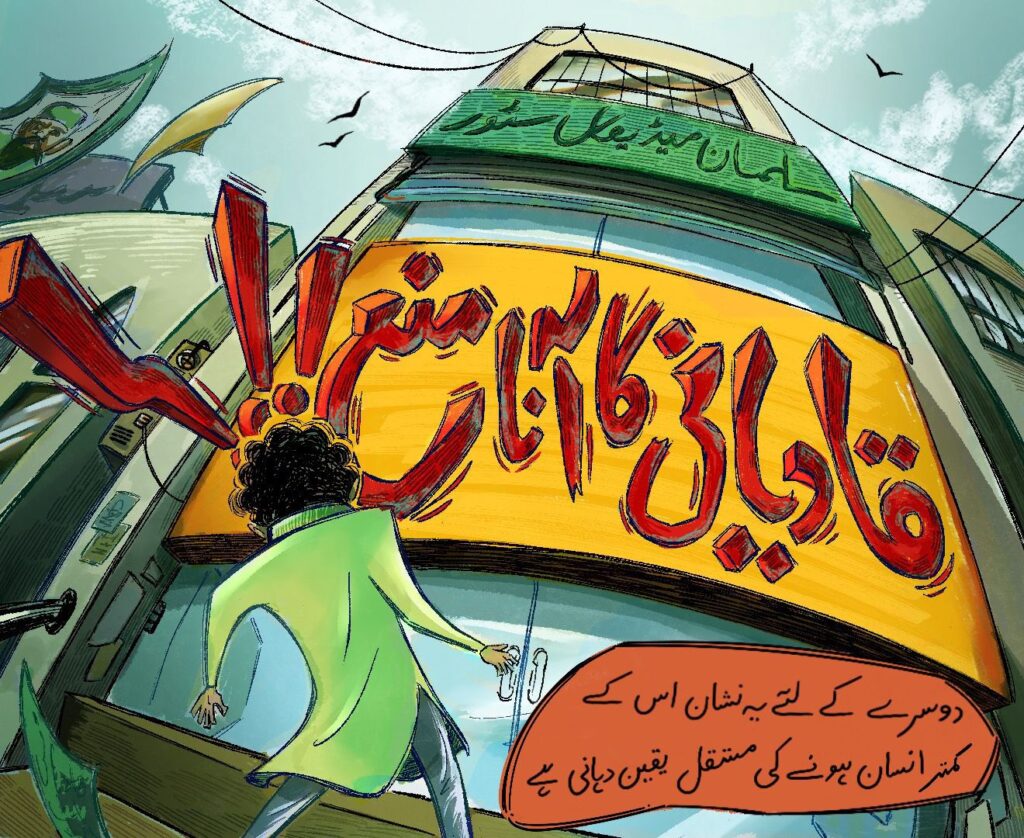

“We look at violence through statistics, but what goes underneath the radar is kids growing up, seeing these signs and slogans as a way to understand these differences,” Mazhar shared. He was referring to the alarming spread of posters and hate speeches calling for violence against those committing blasphemy. Such materials often portray Ahmadi people, and sometimes even directly call out Ahmadis for being “kafir”—disbelievers and ask for them to be banned from certain spaces.

According to Mazhar, the project helped them understand the psychological identity building that underlies the statistics. He added that they encountered more such slogans and prevalence of hate speech in working class areas, such as Sharaqpur, Harbanspura and Chungi Amar Sidhu; these places also show more prevalence of blasphemy cases, as per Amnesty Official statistics.

The concepts of hate and violence—of killing the “blasphemer” as a way of doing a good deed—are introduced to children from a very young age. “For children playing on the street, they are just children to each other,” Allah Rakha said. “But when these children go to the madrassa, they are taught that the other child is different. As children, they are forcefully fed this hatred and misinformation around our practices.”

“If one citizen’s holy book is desecrated or disrespected its punishment is a life sentence, but for another citizen’s book there’s no punishment,” Allah Rakha observed while talking about the discrimination against religious minorities. “There will be someone who has never been to a mosque or read the Quran, but on this issue, they are the first to throw stones or pick up a bottle of petrol.”

A media worker, who is a member of the Engage research team and asked to be identified by the pseudonym Khan, shared that during one of their trips, they were stopped by TLP workers who demanded to know what they were doing. “When TLP especially stopped us, they tried to engage the police and even though we were scared, they were scared too, because they thought we were from intelligence,” he shared. Khan and his team were scared that coming under the radar of TLP workers during their fieldwork would be risky.

The TLP is a religious political party that came about after Mumtaz Qadri was given the death penalty in 2011 for the murder of the Punjab governor Salman Taseer over blasphemy accusations. TLP initially started as Tehreek Rihai Mumtaz Qadri (movement to free Mumtaz Qadri); post Qadri’s hanging in 2016, it was renamed Tehreek-e-Labbaik Ya Rasoolullah, of which TLP is a political wing. Recent blasphemy related violence and lynchings have been linked to a TLP slogan on killing of “blasphemers.”

Khan added that he noticed the extreme sentiments around perceived blasphemy everywhere, manifesting in physical form through the posters and banners. “Even if an adult person looks at these posters, he can be inclined to support them, because we are taught the religious aspect of this from birth. I remember, in class 9, I was taught to be against the “Qadiani kafir” in the Islamiat class, so it’s really ingrained in us and comes back to life when you see such posters. They may just be doing this for the elections, but it changes the way we think.”

As part of Engage’s research, Hussain Mehdi and his team documented slogans and political posters, which mainly included ones that said “Qadianis not allowed”, called for the killing of anyone who insulted the prophet, and claimed Ahmadis were traitors to the state and the religion of Islam.

Mehdi, who led the team of researchers, talked about being joined by progressive students in their work, saying that the students did so because they saw their own spaces and freedom of speech diminishing. Mehdi also attributes the growth in blasphemy-related violence to social media. “Two Ahmadis were murdered in Mandi Bahauddin and the murderer said he had heard a sermon on social media where the preacher said he would go to heaven if he killed them,” he added. Mehdi was referring to the murder of two men in Mandi Bahauddin last June by a 19-year-old man who confessed to both the killings.

As the incendiary materials become part of the public spaces, the values they propagate become entrenched in people’s minds. “The media doesn’t really portray anything because it focuses on the extreme cases,” said Salman Ahmed, a London-based human rights activist who independently advocates for minority rights and is a member of the Ahmadi community. “But in many ways, the lived experience is more important and more hurtful. The media would not focus on that because it’s not big news. I don’t think the media reflects anything.” As he did not grow up in Pakistan, but moved there in his 20s, Ahmed said he perceived his identity very differently from Ahmadis who had grown up constantly surrounded by violent, exclusionary slogans and materials in the public sphere.

“Soon after I had moved to Pakistan, I travelled to Kashmir and ended up talking to someone outside of a mosque who was collecting donations,” Ahmed recalled. “While I didn’t tell him outright that I was an Ahmadi, it soon became obvious through my conversation. All of a sudden, he started saying, ‘I think you’re reading illegal materials,’ and then people came out and surrounded our car.” It was the first time he realised how much his identity mattered in Pakistan’s public sphere.

“The widespread public expressions of hatred necessitate examining how different groups experience blasphemy laws differently,” Ahmed continued. “For Ahmadis, these laws challenge their very identity and religious existence. Other minorities face different challenges—for them, the laws often represent a requirement to acknowledge Muslim predominance in Pakistan, accepting that their actions and words will always be subordinate to those of their Muslim counterparts. Within the Muslim community itself, the laws have evolved into a tool to assert dominance, suppress those with differing interpretations, and to establish claims of religious authenticity.”

“I think one of the problems with conversations around minority communities in Pakistan, is that everyone is lumped together,” Ahmed said. “You also need to let minorities speak for themselves and that is non-existent.”

Perception of blasphemy beyond courts

Blasphemy accusations in Pakistan can carry severe extra-judicial consequences. While higher courts often overturn blasphemy convictions, the initial accusations can trigger immediate and dangerous responses. Vigilante violence has targeted a wide range of individuals, including religious minorities, politicians, students, clerics, and people with mental disabilities. These extrajudicial actions underscore the broader social tensions surrounding blasphemy allegations in the country, revealing a complex and volatile legal and social landscape where accusations can have life-threatening implications.

The ingrained belief in the blasphemy law is why these killings—and violence in general—often take place well before the issue has had a chance to enter the legal system. This is also possibly the first step in understanding the existence of blasphemy in the social and psychological dimension, which has a far greater impact than the law itself. The two can’t be separated entirely, as the political anthropologist Arsalan Khan pointed out. “The social and legal dimensions of blasphemy are not easily distinguished,” Khan, author of The Promise of Piety: Islam and The Politics of Moral Order, told the reporter. “The blasphemy mobs generally claim, ‘we are enforcing the writ of state because the people in power fail to enforce it.’ So, the power of the law is always at play, and I don’t know if it’s useful to differentiate the legal and the social in that way. The law is never not operative in the political mobilisation against blasphemy.”

Cases like the murder of Salman Taseer, and the subsequent execution of his murderer Mumtaz Qadri, brought global attention to this phenomenon. But for many Pakistanis, the high-profile cases are only small parts of an ideology that shapes their daily lives. While the law appears front and centre of media reporting, it is the social phenomenon of blasphemy that is far more entrenched in the lives of Pakistanis.

“I think the issue with the media is they only look at the big stuff, for example, Jaranwala, but if you look at that locality, those people would have had problems for years,” Ahmed said. He was referring to a 2023 mob attack on churches and Christians over blasphemy allegations in Jaranwala town of Faisalabad district. “They don’t see everyday discrimination, they only see the grander stuff,” he added.

Saad Lakhani, an anthropologist who focuses on Islam and has conducted extensive field work with the Barelvi groups—and specifically on the TLP, in Pakistan—found that blasphemy accusations were an everyday occurrence for countless communities and neighbourhoods across the country. “Blasphemy has always been presented as the end of the world, but it has never been the end of the world,” said Lakhani. “It is a daily thing, part of everyday life. Everything can be blasphemy and everybody knows that, so anything can become an excuse.”

“I did my work in Sharaqpur outside Lahore and it was an everyday affair,” Lakhani continued. “It didn’t even get to the point of the law getting involved. One group would rip another group’s poster; each side would bring their men, hurl accusations, make threats of violence, and ultimately the police and elders would sort it out. There wouldn’t even be an FIR or any report filed.”

In his findings, Lakhani noted that more often than not, Sunni Muslims themselves become victims to blasphemy accusations as much of blasphemy violence is used as a tool for sectarian politics. Mufti Tariq Masood’s case made headlines this year when the cleric who called for the death of blasphemers himself became accused of blasphemy. The critics of the law pointed out that if the religious leadership truly believed that the law was just, Masood would have submitted to the will of the law. However, his apology, along with his high social standing in religious spaces have allowed him to remain unharmed for now.

Lakhani also connects the perceptions of blasphemy and its psycho-social hold on society to the Muslim identity and the shift in its perception, which he finds rooted in the idea of a ‘Ghazi’.

Ilmuddin, a Muslim carpenter in pre-partition India, killed a Hindu publisher, Ram Pal, for publishing a book that he found derogatory to the Prophet Muhammad. He was inspired by a speech at his local mosque, and over 80 years later, many Pakistanis still call him a Ghazi and visit his grave.

Ilmuddin ignited the belief of a Muslim Ghazi standing up for himself and his religion—and this belief permeated into the Muslim-Pakistani identity. Since then, the same belief has been twisted and convoluted so that even when many Muslim groups claim to be united over the issue of blasphemy, it is also the most divisive element found in society. It only takes a minor disagreement for someone to point a finger, accuse someone of blasphemy and the mob mentality does the rest.

In both Lakhani and Khan’s fieldwork, it quickly became clear that blasphemy-related politics was popular amid a certain segment of young, working-class Muslim men. Lakhani connects this trend to the great promise of religiosity in Pakistani society. He explains that these working-class men feel frustrated due to the lack of recognition of their religious efforts, and don’t have the time or resources to perform religion in the way that society expects them to. And so, they turn to the fight against the ‘blasphemer’ as their contribution to religion.

“There’s the belief that the Islamic society will bring a just order, and the blasphemer destroys that order by rupturing the relationship to God,” Khan said. “I think the frustration is generated by economic and political problems, and blasphemy becomes a crystallisation of these frustrations.”

After the increase in the TLP’s mobilising, which started well before the TLP actually named itself a political party, things started changing, Lakhani noted. “There was a narrative shift. These are no longer symbols of national unity but instead of class warfare—imagine working class heroes standing up against treasonous elites,” he said.

In some ways, blasphemy is perhaps one of the most popular issues across class, religion, and region in Pakistan. “Even if we get rid of the laws, what will happen?” Lakhani asked, adding that, “The violence is primarily embedded in popular culture and mostly occurs outside the legal framework. We give too much agency to the law and it’s tiresome.”

In 2024, a group of researchers and activists set out on a challenging mission: to map out instances of hate speech and blasphemy-related violence across Pakistan. A member of the research team, who wished to remain anonymous, said their work focused on documenting posters and slogans on blasphemy and not talking to people. But when they spoke to people, they had to pretend that they supported the blasphemy laws. “I was in a shop, and took a picture of a poster without consent,” he recalled one incident. The poster called for attacking or killing anyone who “disrespected” Prophet Muhammad. “The shop owner grabbed me and asked: what are you doing? So, I had to tell him I thought this [the poster] was cool.”

In another incident of confrontation during field documentation, he had to misrepresent his views on the persecuted minority Ahmadis to ensure his own safety. “I took a picture in a mosque, and then the imam called me and asked what I was doing. I told him the Ahmadi community is against Islam, and after that, all the people around me turned 180 degrees in their attitude. They even gave me many of their pamphlets,” he narrated.

The concept of blasphemy—or Gustakhi, as it is called in Urdu—is deeply entrenched within the Muslim-Pakistani identity and within the Pakistani society as a whole. The laws only bolster this aspect.

Pakistan’s laws on “offences relating to religion”, commonly known as “blasphemy laws”, lay down an array of crimes and their punishment—from “defiling” the Quran, to “deliberate and malicious” acts outraging religious sentiment and using derogatory remarks in respect of the Prophet Muhammad. The vague definition of desecration in the laws creates a significant challenge: even discussing or critiquing the laws could potentially be interpreted as blasphemy. This ambiguity has emboldened many citizens to take enforcement into their own hands, resulting in increased vigilante violence against both alleged blasphemers and critics of the law itself. The situation is further exacerbated by law enforcement’s frequent reluctance to intervene in blasphemy-related incidents, making it nearly impossible to maintain public order in such cases.

The laws, which comprise multiple sections of the penal code, create an atmosphere of fear in the country. According to the US Department of State, as well as non-governmental reports over the years, the law disproportionately affects religious minorities, and its provisions are used as pretext for mob-led violence against the accused. Although there is a lack of official data on blasphemy-related cases and violence, due to many cases not being registered with the police, the available sources indicate that cases only continue to rise, and the laws are used to carry out political and social vendetta.

The researchers mapping out blasphemy violence last year were working with Engage Pakistan, a nonprofit advocacy group working on blasphemy laws. Their research reveals how the country’s blasphemy laws cause an increase in violence and fear that do not reach the courtrooms. Through their documentation of hate speech and inflammatory posters across the country, the researchers observed how blasphemy accusations have become tools for social control and persecution. The US Commission on International Religious Freedom cites that at least 53 people were in custody under blasphemy charges across Pakistan as of 2023. However, the report shows that these numbers barely scratch the surface of how the law shapes social dynamics and enables persecution, particularly of religious minorities, through the constant threat of accusation.

Regardless of whether the matter is in court or outside, the fear of accusation remains the same. Lazar Allah Rakha, a Christian human-rights lawyer who has represented many of those accused of blasphemy, points out that in a lot of these cases, issues around blasphemy accusations and violence become more dangerous for the accused when they come to court because the case then comes into the public eye. “Please sort these issues out before bringing them to court. The more open it is, the more danger it puts people in,” Allah Rakha said.

Understanding the blasphemy laws

The colonial era blasphemy laws, retained by Pakistan’s Penal Code, were further strengthened in the 1980s under General Zia-ul-Haq’s military government. Eventually, blasphemy was made punishable by death in 1986. Section 295-C was introduced into the Penal Code, which states: “Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine.” Clauses under Section 295 also comprises punishments for desecration of the Quran and other offences deemed insulting to Islam.

While an increased use of the law is often attributed to Haq, his predecessor Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto also made contributions. In 1974, under Bhutto, Pakistan’s parliament unanimously passed a constitutional amendment declaring the Ahmadiyya community as non-Muslim. This move was largely in response to widespread riots and protests that demanded such a declaration. The amendment altered Article 260 of the Constitution, officially classifying Ahmadis as non-Muslims. This legislative change not only marginalised the Ahmadiyya community but also laid the groundwork for more stringent blasphemy laws in the country.

After these past leaders, both civilian leaders and military rulers have kept the laws alive. Critics often ignore the ways more recent political leaders have also endorsed the law. Khadim Rizvi, founder of the hardliner Tehreek E Labbaik Pakistan, and even the populist leader Imran Khan, have both endorsed the law and backed efforts to protect it. On the other hand, activists who have been calling for a removal—or at least amendment—of the law have long been disregarded. In fact, attempts made in 2010 to amend the law were withdrawn due to pressures from religious groups and death threats to the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP) senator Sherry Rehman, who had proposed the amendments.

Qibla Ayaz, a former chairperson of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII), which is the country’s top religious advisory body, told the BBC in 2019 that the government was not ready to change the blasphemy law in fear of backlash. Further, his suggestions for penalties over misuse of the law were not implemented.

Critics of the law also note its misuse in persecution of religious minorities. The advocate Allah Rakha pointed out that a law is meant to ensure equality through equal rights, but the blasphemy law does not do that. “We see if one citizen’s holy book is desecrated or disrespected, its punishment is life sentence, but for another citizen’s book, there is no punishment,” he said. “People can have different religions. The state does not have a religion, but we have started considering the state as a person, and not an institution of governance.”

In late January 2025, four people were convicted for committing blasphemy online. The trial court sentenced the convicts to death under Section 295-C, life imprisonment under Section 295-B of the penal code, and ten years of imprisonment along with a fine of Rs 100,000 each under Section 295-A. Under Section 298-A, the convicts were sentenced to three years of imprisonment and fined Rs 100,000 each. Under the Prevention of Electronic Crime Act (PECA) Act 2016, the convicts were sentenced to seven years of imprisonment and fined Rs 100,000 each.

International organisations have estimated that up till 2022, 40 people had been tried for blasphemy in Pakistan, but no executions took place. On the other hand, at least 89 vigilante killings were recorded in relation to blasphemy accusations between 1947 and 2021. While court cases and deaths in relation to this issue are the most obvious way to record blasphemy violence, such data does not cover the whole issue because the everyday violence, accusations and fear that permeate through society cannot be counted as easily.

A cornered judiciary

The blasphemy laws resurfaced as a central issue in August last year as religious ire led the judiciary to revisit the Mubarak Sani case. Sani, who belongs to the minority Ahmadi community, was acquitted in February 2024 after having been accused under the Punjab Holy Quran (Printing and Recording) Amendment Act 2021, which criminalises the unauthorised printing, recording, and distribution of the Holy Quran and its extracts, both physically and digitally. The Supreme Court bench led by the chief justice decided that Sani had distributed the Ahmadi religious text before the act had become criminalised, leading to his acquittal, and noted that he had already served 13 months in prison. The maximum punishment for the offence is six months.

Sani was also charged under some blasphemy laws—Sections 295-B and 298-C—which criminalise the desecration of the Quran and prohibit members of the Ahmadi community from identifying as Muslims or preaching their faith. However, the Supreme Court noted that the First Information Report (FIR) and police investigation contained no evidence to support these charges.

The approximately 500,000-strong Ahmadi or Ahmadiyya community in Pakistan is a religious minority that considers itself Muslim but the blasphemy laws bar them from referring to themselves as such, and from practising aspects of their faith. While all minority communities in Pakistan face some sort of discrimination, Ahmadis particularly come under threat because many Sunni groups see them as changing Islam, which they perceive to be a threat.

The constitution has branded them non-Muslims since 1974, and a 1984 law forbids them from even claiming their faith as Islamic. Unlike in other countries, they cannot refer to their places of worship as mosques, make the call to prayer, or travel on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca. The blasphemy laws mainly target Ahmadis but are also used against other minorities in an effort to “preserve Islam”.

Sani’s acquittal in February 2024 stirred up controversy. In July, the Supreme Court revisited the case after calls for review by religious political parties like Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam – Fazl (JUI-F), Jamaat-e-Islami, and Tehreek E Labbaik Pakistan, and a petition filed by the Punjab government. It accepted the review petition and said Ahmadis in Pakistan could practice their faith privately, but not publicly use Muslim terms or identify as Muslims. The court argued that the offences listed under sections 298 A, B and C—which deal with offences against religious sentiments—only applied when done publicly.

The judgment prompted fresh objections and protests near the Supreme Court premises by parties who believed that Ahmadis should not be allowed to practice their beliefs. The Supreme Court then held a second “review”—although it was termed a “correction”—in August. The correction led to the redaction of certain paragraphs from the verdict, such as those stating Ahmadis were allowed to privately practice their religion. Article 20 of Pakistan’s Constitution confers citizens with the right to profess and practice their religions. But the court redacted the observation from the judgment, noting that it went against laws that banned disrespect of the Quran.

The top court also issued a direction that the expunged paragraphs would not be used as precedent in the future and instructed the trial court hearing the Mubarak Sani case to not be influenced by the two prior judgments.

Sani’s case is one of many in Pakistan where Ahmadis have been accused of disrespecting Prophet Muhammad or the Quran, and faced protracted legal trials, and even mob violence. What should have been an easily wrapped-up case, ended up going through two reviews under pressure from religious groups. Noting the significance of this development, Khalid Ranjha, a senior lawyer and a former federal minister for law and justice, told voicepk.net that the Supreme Court had never before heard a matter after the review petition was already decided. He also warned that this could enable the government to appeal to overturn other judgements in the future.

Since the Supreme Court revisited the case, concerns have risen around how religious and political pressures are influencing the judiciary and weakening its independence. Many activists and advocates of free speech have criticised the increasing use of the blasphemy laws and the control these give right-wing religious leaders over the Pakistani society as a whole. The increased control and pressure have led to fear among minority groups in particular. Amir Mehmood, a spokesperson for the Ahmadi community in Pakistan, points out that almost no lawyers want to represent such cases anymore because they fear the consequences that come with the association. But it is not just minorities who are at risk; Mehmood said, “Ab rahi nahin koi baat khatre ki, ab sab ko sabhi se khatra hain (Now there is no issue of danger as everyone is at risk from everyone).”

In September, his words were proven true in the case of Mufti Tariq Masood, who was forced to spend several days apologising for saying that the Quran appeared to have grammatical mistakes. Despite clarifying that he was talking about perceptions, Masood, a prominent cleric and religious leader, has been getting severe threats and has even released a video saying he feared something would happen to him.

It’s a story Pakistan has seen time and again, each time with similar criticisms, reporting, and the absence of any subsequent change.

Propagation of hate and intolerance

When Arafat Mazhar, the director of Engage Pakistan, a non-profit organisation that aims to reform the country’s blasphemy law, and his team decided to investigate hate speech and blasphemy-related violence in 2024, they sought to highlight its pervasiveness and normalisation in Pakistani society. The researchers conducted their work across working class areas in Punjab over the last year.

“We look at violence through statistics, but what goes underneath the radar is kids growing up, seeing these signs and slogans as a way to understand these differences,” Mazhar shared. He was referring to the alarming spread of posters and hate speeches calling for violence against those committing blasphemy. Such materials often portray Ahmadi people, and sometimes even directly call out Ahmadis for being “kafir”—disbelievers and ask for them to be banned from certain spaces.

According to Mazhar, the project helped them understand the psychological identity building that underlies the statistics. He added that they encountered more such slogans and prevalence of hate speech in working class areas, such as Sharaqpur, Harbanspura and Chungi Amar Sidhu; these places also show more prevalence of blasphemy cases, as per Amnesty Official statistics.

The concepts of hate and violence—of killing the “blasphemer” as a way of doing a good deed—are introduced to children from a very young age. “For children playing on the street, they are just children to each other,” Allah Rakha said. “But when these children go to the madrassa, they are taught that the other child is different. As children, they are forcefully fed this hatred and misinformation around our practices.”

“If one citizen’s holy book is desecrated or disrespected its punishment is a life sentence, but for another citizen’s book there’s no punishment,” Allah Rakha observed while talking about the discrimination against religious minorities. “There will be someone who has never been to a mosque or read the Quran, but on this issue, they are the first to throw stones or pick up a bottle of petrol.”

A media worker, who is a member of the Engage research team and asked to be identified by the pseudonym Khan, shared that during one of their trips, they were stopped by TLP workers who demanded to know what they were doing. “When TLP especially stopped us, they tried to engage the police and even though we were scared, they were scared too, because they thought we were from intelligence,” he shared. Khan and his team were scared that coming under the radar of TLP workers during their fieldwork would be risky.

The TLP is a religious political party that came about after Mumtaz Qadri was given the death penalty in 2011 for the murder of the Punjab governor Salman Taseer over blasphemy accusations. TLP initially started as Tehreek Rihai Mumtaz Qadri (movement to free Mumtaz Qadri); post Qadri’s hanging in 2016, it was renamed Tehreek-e-Labbaik Ya Rasoolullah, of which TLP is a political wing. Recent blasphemy related violence and lynchings have been linked to a TLP slogan on killing of “blasphemers.”

Khan added that he noticed the extreme sentiments around perceived blasphemy everywhere, manifesting in physical form through the posters and banners. “Even if an adult person looks at these posters, he can be inclined to support them, because we are taught the religious aspect of this from birth. I remember, in class 9, I was taught to be against the “Qadiani kafir” in the Islamiat class, so it’s really ingrained in us and comes back to life when you see such posters. They may just be doing this for the elections, but it changes the way we think.”

As part of Engage’s research, Hussain Mehdi and his team documented slogans and political posters, which mainly included ones that said “Qadianis not allowed”, called for the killing of anyone who insulted the prophet, and claimed Ahmadis were traitors to the state and the religion of Islam.

Mehdi, who led the team of researchers, talked about being joined by progressive students in their work, saying that the students did so because they saw their own spaces and freedom of speech diminishing. Mehdi also attributes the growth in blasphemy-related violence to social media. “Two Ahmadis were murdered in Mandi Bahauddin and the murderer said he had heard a sermon on social media where the preacher said he would go to heaven if he killed them,” he added. Mehdi was referring to the murder of two men in Mandi Bahauddin last June by a 19-year-old man who confessed to both the killings.

As the incendiary materials become part of the public spaces, the values they propagate become entrenched in people’s minds. “The media doesn’t really portray anything because it focuses on the extreme cases,” said Salman Ahmed, a London-based human rights activist who independently advocates for minority rights and is a member of the Ahmadi community. “But in many ways, the lived experience is more important and more hurtful. The media would not focus on that because it’s not big news. I don’t think the media reflects anything.” As he did not grow up in Pakistan, but moved there in his 20s, Ahmed said he perceived his identity very differently from Ahmadis who had grown up constantly surrounded by violent, exclusionary slogans and materials in the public sphere.

“Soon after I had moved to Pakistan, I travelled to Kashmir and ended up talking to someone outside of a mosque who was collecting donations,” Ahmed recalled. “While I didn’t tell him outright that I was an Ahmadi, it soon became obvious through my conversation. All of a sudden, he started saying, ‘I think you’re reading illegal materials,’ and then people came out and surrounded our car.” It was the first time he realised how much his identity mattered in Pakistan’s public sphere.

“The widespread public expressions of hatred necessitate examining how different groups experience blasphemy laws differently,” Ahmed continued. “For Ahmadis, these laws challenge their very identity and religious existence. Other minorities face different challenges—for them, the laws often represent a requirement to acknowledge Muslim predominance in Pakistan, accepting that their actions and words will always be subordinate to those of their Muslim counterparts. Within the Muslim community itself, the laws have evolved into a tool to assert dominance, suppress those with differing interpretations, and to establish claims of religious authenticity.”

“I think one of the problems with conversations around minority communities in Pakistan, is that everyone is lumped together,” Ahmed said. “You also need to let minorities speak for themselves and that is non-existent.”

Perception of blasphemy beyond courts

Blasphemy accusations in Pakistan can carry severe extra-judicial consequences. While higher courts often overturn blasphemy convictions, the initial accusations can trigger immediate and dangerous responses. Vigilante violence has targeted a wide range of individuals, including religious minorities, politicians, students, clerics, and people with mental disabilities. These extrajudicial actions underscore the broader social tensions surrounding blasphemy allegations in the country, revealing a complex and volatile legal and social landscape where accusations can have life-threatening implications.

The ingrained belief in the blasphemy law is why these killings—and violence in general—often take place well before the issue has had a chance to enter the legal system. This is also possibly the first step in understanding the existence of blasphemy in the social and psychological dimension, which has a far greater impact than the law itself. The two can’t be separated entirely, as the political anthropologist Arsalan Khan pointed out. “The social and legal dimensions of blasphemy are not easily distinguished,” Khan, author of The Promise of Piety: Islam and The Politics of Moral Order, told the reporter. “The blasphemy mobs generally claim, ‘we are enforcing the writ of state because the people in power fail to enforce it.’ So, the power of the law is always at play, and I don’t know if it’s useful to differentiate the legal and the social in that way. The law is never not operative in the political mobilisation against blasphemy.”

Cases like the murder of Salman Taseer, and the subsequent execution of his murderer Mumtaz Qadri, brought global attention to this phenomenon. But for many Pakistanis, the high-profile cases are only small parts of an ideology that shapes their daily lives. While the law appears front and centre of media reporting, it is the social phenomenon of blasphemy that is far more entrenched in the lives of Pakistanis.

“I think the issue with the media is they only look at the big stuff, for example, Jaranwala, but if you look at that locality, those people would have had problems for years,” Ahmed said. He was referring to a 2023 mob attack on churches and Christians over blasphemy allegations in Jaranwala town of Faisalabad district. “They don’t see everyday discrimination, they only see the grander stuff,” he added.

Saad Lakhani, an anthropologist who focuses on Islam and has conducted extensive field work with the Barelvi groups—and specifically on the TLP, in Pakistan—found that blasphemy accusations were an everyday occurrence for countless communities and neighbourhoods across the country. “Blasphemy has always been presented as the end of the world, but it has never been the end of the world,” said Lakhani. “It is a daily thing, part of everyday life. Everything can be blasphemy and everybody knows that, so anything can become an excuse.”

“I did my work in Sharaqpur outside Lahore and it was an everyday affair,” Lakhani continued. “It didn’t even get to the point of the law getting involved. One group would rip another group’s poster; each side would bring their men, hurl accusations, make threats of violence, and ultimately the police and elders would sort it out. There wouldn’t even be an FIR or any report filed.”

In his findings, Lakhani noted that more often than not, Sunni Muslims themselves become victims to blasphemy accusations as much of blasphemy violence is used as a tool for sectarian politics. Mufti Tariq Masood’s case made headlines this year when the cleric who called for the death of blasphemers himself became accused of blasphemy. The critics of the law pointed out that if the religious leadership truly believed that the law was just, Masood would have submitted to the will of the law. However, his apology, along with his high social standing in religious spaces have allowed him to remain unharmed for now.

Lakhani also connects the perceptions of blasphemy and its psycho-social hold on society to the Muslim identity and the shift in its perception, which he finds rooted in the idea of a ‘Ghazi’.

Ilmuddin, a Muslim carpenter in pre-partition India, killed a Hindu publisher, Ram Pal, for publishing a book that he found derogatory to the Prophet Muhammad. He was inspired by a speech at his local mosque, and over 80 years later, many Pakistanis still call him a Ghazi and visit his grave.

Ilmuddin ignited the belief of a Muslim Ghazi standing up for himself and his religion—and this belief permeated into the Muslim-Pakistani identity. Since then, the same belief has been twisted and convoluted so that even when many Muslim groups claim to be united over the issue of blasphemy, it is also the most divisive element found in society. It only takes a minor disagreement for someone to point a finger, accuse someone of blasphemy and the mob mentality does the rest.

In both Lakhani and Khan’s fieldwork, it quickly became clear that blasphemy-related politics was popular amid a certain segment of young, working-class Muslim men. Lakhani connects this trend to the great promise of religiosity in Pakistani society. He explains that these working-class men feel frustrated due to the lack of recognition of their religious efforts, and don’t have the time or resources to perform religion in the way that society expects them to. And so, they turn to the fight against the ‘blasphemer’ as their contribution to religion.

“There’s the belief that the Islamic society will bring a just order, and the blasphemer destroys that order by rupturing the relationship to God,” Khan said. “I think the frustration is generated by economic and political problems, and blasphemy becomes a crystallisation of these frustrations.”

After the increase in the TLP’s mobilising, which started well before the TLP actually named itself a political party, things started changing, Lakhani noted. “There was a narrative shift. These are no longer symbols of national unity but instead of class warfare—imagine working class heroes standing up against treasonous elites,” he said.

In some ways, blasphemy is perhaps one of the most popular issues across class, religion, and region in Pakistan. “Even if we get rid of the laws, what will happen?” Lakhani asked, adding that, “The violence is primarily embedded in popular culture and mostly occurs outside the legal framework. We give too much agency to the law and it’s tiresome.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.