Who’s Running the Monkey Business: A Social Geography Of Delhi In Eeb Allay Ooo!

Delhi is simultaneously everyone’s city and nobody’s city. It is home to the highest number of migrant workers in India, with 21 percent of its population composed of external migrants, predominantly from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. These communities have created cultural enclaves scattered throughout the city, making Delhi a diverse yet ambiguous socio-cultural milieu.

Prateek Vats’ 2019 film, Eeb Allay Ooo!, explores the life of Anjani Prasad (Shardul Bharadwaj), a monkey-repeller in New Delhi, and traces the practice of monkey chasing, a community-driven craft originating from contractual laborers in the capital. The filmmaker draws from his experiences as a second-generation Bihari migrant in Delhi, and attempts to make sense of home and belonging. Being a resident and student in Delhi, Vats was motivated to make his debut feature film on the question of monkey-repellers’ response to the world around them, which, he says, “thrives on depriving its people of their dignity.”

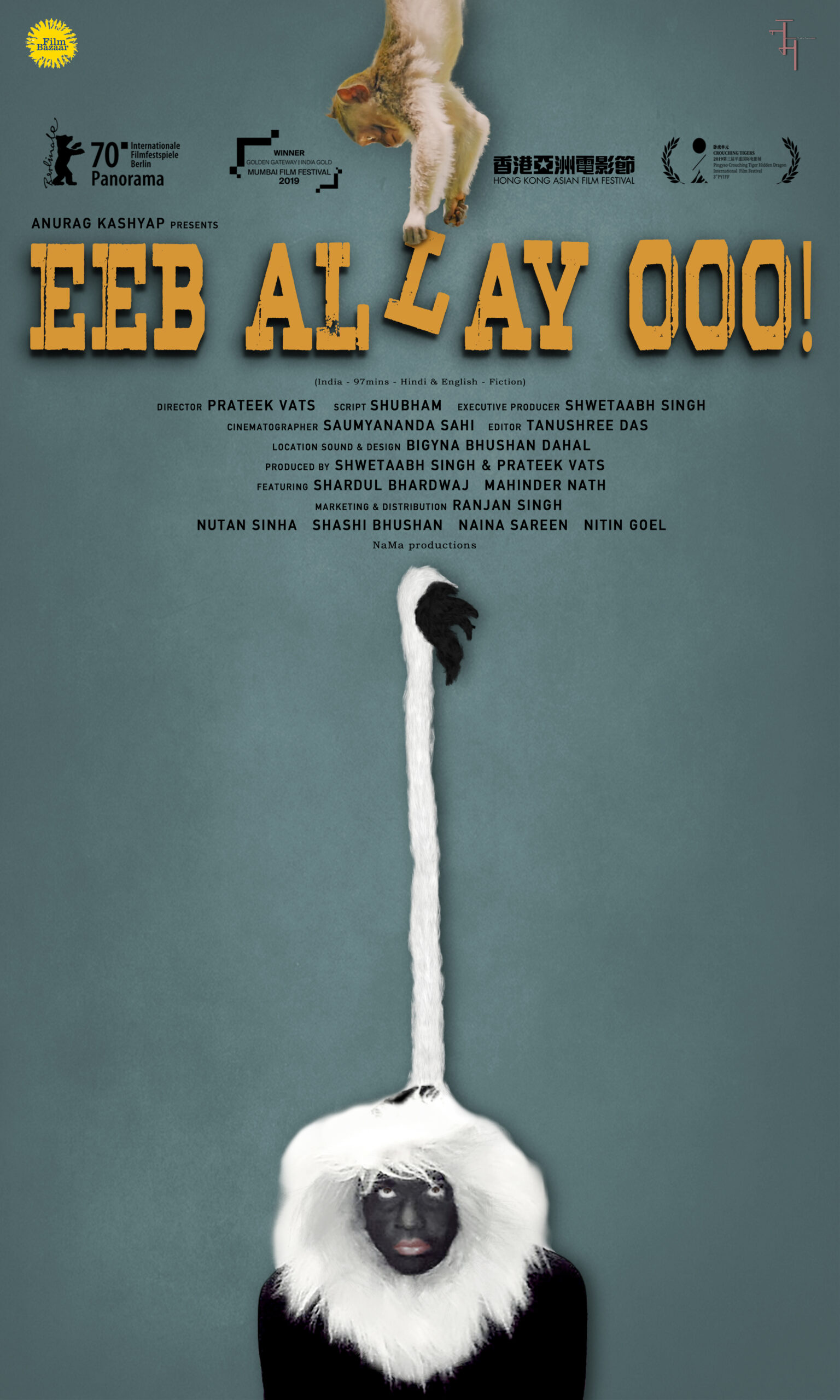

The official poster of Eeb Allay Ooo! captivates its viewers through an orientalized image of the Karnatic langur, showing Anjani having painted himself black and wearing a sharp, white, furry costume to mimic a langur. This get-up serves a dual purpose: it is intended to scare away monkeys, while simultaneously providing an exotic, orientalist spectacle, particularly for tourists. But the film ultimately tells the tale of those who make the city liveable but cannot live in it themselves. It maps the relationship between Delhi, the heart of Indian democracy, and the monkey menace, to uncover the forgotten actors of the story—the monkey chasers.

The peculiar case of macaque monkeys in Delhi reflects the tussle between fascination and repulsion, sanctity, and rambunctiousness. Driven from their natural habitats in search of food and shelter, these monkeys have migrated to urban areas, mirroring the broader patterns of human migration. As Delhi evolves into a sanitized hub of modernity and urban governance, monkeys— as perceived pests— have become an inconvenient and often embarrassing issue, largely absent from the global G20-esque headlines. This migration has also led to monkey-repellers—individuals or services, hired to manage and remove the animals from urban spaces using a combination of mimicry and langur costumes. Until recently, the repellers coexisted harmoniously with langurs— considered natural predators of macaque monkeys— and even relied on them as part of their trade practices. After an environmentalist ban was imposed on using langurs for commercial purposes, the monkey-repellers were forced to resort to mimicking the calls of their erstwhile partners to scare the macaque prey away.

Their skill of mimicking predatory animals has a distinguished provenance, evolved through their everyday interactions. However, these techniques are being diluted, their creators displaced, and their profits increasingly reaped by contractors, technocrats, and even AI policy-makers. The dichotomy of the monkey and the man is fleshed out amidst the rise of conservative values, leading the former, as deities of Delhi, to have firmer rights to the city than the latter.

While the state has been hesitant to use stringent measures to remove monkeys due to pressure from environmentalists, it had no qualms about leaving its migrant population starved and destitute amid a global pandemic. Vats captures these contradictions with an astute elegance. Beneath its quirky facade, Eeb Allay Ooo! tells a poignant story of a powerless man in a powerful place.

The Performance of Monkey-Repelling

The practice of monkey capture is not a mere caper or a product of trivial tricks; rather, its history reflects a profound understanding of simian behavior, empathy, and warmth, which challenges prevailing misconceptions about the wild. Consider, for instance, the case of Gul Khan, a professional monkey chaser in New Delhi for over three decades. Khan’s expertise is grounded in his relational understanding of langurs.

His family lived with the langurs, cared for them, and even shared meals with them as though they were household members, and their deep understanding of the langurs profoundly informs their trade. The mirroring of their voice, gestures, and emotions is essential to their partnership.

The craft of monkey chasing traces its lineage to the Kalandar tradition—a community of performers and dancers who historically entertained the urban populace. Khan notes monkey chasers employ a distinct language—he frequently produces high-pitched, sharp sounds to deter monkeys. “Triooo! Oooo!” he exclaims, mimicking the langur’s call, causing the monkeys to retreat.

Consequently, the words employed by Khan, and by Anjani in Eeb Allay Ooo!, are neither erratic nor random; they are deeply embedded in a history of human experience, signifying a covenant between humans and non-humans. These oral calisthenics—diction, cadence, and tone—represent a labor of love, honed through consistent practice.

However, recent state policies have systematically eroded this trade, precipitating its decline. Many Kalandar families, including Gul Khan’s, adapted to monkey chasing as a means of survival—only to witness their livelihood appropriated by corporate and state actors in yet another painful reminder of deliberate disenfranchisement.

The pervasive start-up ecosystem, for example, has dipped its toes in the monkey business. Bengaluru-based company Katidhan, platformed on Shark Tank India, recently introduced an advanced sound-programming device to detect and deter monkeys. The start-up claims to be easing farmers’ misery, although the device carries a hefty price tag of $130 and relies on sonic strategies created by contractual migrant workers. In 2019, Microsoft publicly introduced an AI project that had been funded to build a large geolocation database of Delhi’s monkeys and allow animal control officers to identify and sterilize them.

For experienced monkey-chasers like Gul Khan, however, the personalities and politics of these monkey troops have been inscribed onto their memories. Years of working in the profession have allowed them to develop familiarity with the distinct troops that reside in each neighborhood, and the diverse approaches the monkeys adopt in response to the repellers. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani learns to identify the alpha male head of each troop and recognize the distinct temperaments of the monkeys that frequent Lutyens’ Delhi. The film’s title thus serves as both an homage to the origins of this art and a critique of its increasingly co-opted etymology.

The practice of repelling shapes the geography of urban life, influencing domestic economies, social life, and beyond. Many monkey chasers, such as Khan, live close to the langurs they work with and are compensated with a daily wage of approximately INR 643 (USD 7.62) for eight hours of work. After a 2021 government decision banned the use of langurs themselves, Khan and others had to let go of their langur companions and develop an entirely new mimicry skill to perform their job. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani is chastised for his newfangled chasing methods such as cardboard cut-outs or costumes resembling langurs.

The creativity of both reel and real monkey-repellers is met with apathy or disdain, while the state endorses the same strategies under the guise of research and innovation. Owing to their class and caste identities, monkey-chasers are never approached to contribute to the creation of scientific knowledge regarding their work. Despite numerous bureaucratic measures, the city’s municipal authorities have been unwilling to recognize and legitimize the status of monkey-repellers.

As a result, they often reside in informal settlements and bastis, distanced from the Lutyens belt. Efforts to separate the artisan from the art are an insult to the integrity of their craft and the social contexts underpinning its creation. The precarity of these migrant workers of Delhi is invisibilized in favor of profits reaped using the techniques of their labor. The last census was conducted more than 13 years ago, in 2011. The dearth of accurate data on the conditions of migrant laborers discloses the state’s apathy toward informal workers and its rapid retreat from welfare services.

The Fragility of Informal Labor

The informal sector in Delhi constitutes the city’s backbone. Eeb Allay Ooo! interrogates the question of migrant labor—who performs it, for whose benefit, and who holds dominion over it. The one-bedroom house shared by Anjani, his sister (Nutan Sinha), and his brother-in-law (Shashi Bhushan) becomes a microcosm of this urban economy. Each of them is an informal worker, entangled in precarious employment marked by minimal job security, unsustainable working hours, and an absence of healthcare—trapping them in a cycle of persistent poverty.

As the film slowly peels its onion, we are confronted with the fragility of informal labor, even when it serves the highest echelons of power, such as bureaucrats and parliamentarians. In one scene, Anjani meekly responds to his sister that he does not hold a sarkari (government) job but a sarkari-jaisi naukri (appears like a government job), underscoring how proximity to privilege has failed to translate into benefits or social security. Residents of impoverished settlements, often excluded from formal welfare frameworks, must find dignity through livelihood diversification and their limited access to social capital.

In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani’s employment in Lutyens becomes a point of pride for his sister, who shares this fact with her doctor at the government clinic. Anjani’s access to social capital also creates opportunities for supplementary income, as he poses for tourists and foreigners who photograph him in his langur costume. The oddness of his costume makes him look out of place, exotic, and the perfect spectacle for a tourist seeking a quirky India photo. He uses this oddity and ingenuity to his advantage by charging the tourists a fee.

However, this act of ingenuity results in his dismissal when a religious, Hanuman-devout councilor lodges a complaint following the circulation of his viral videos on social media. Thus, one of the rare moments of laughter in Eeb Allay Ooo!—Anjani becoming “viral” in his get-up—comes to a cruel and abrupt end. Anjani losing his job highlights the undemocratic practices that underpin informal and gig work. It underscores the lack of agency or influence workers have over their methods of labor, where any effort to improve the indignities of their conditions is viewed as insubordination, and punished.

Like Anjani, countless informal and essential workers shoulder dangerous work to make the city habitable, and aspirational. Yet they remain excluded from its promises, unable to inhabit, or thrive, within it. These divisions and displacement ripple outward, forcing thousands of migrants to relocate far from the city core. In an ethnographic study on monkey capture in Delhi by Ajay Gandhi, Yusuf, a resident of East Delhi’s slums—home to many monkey catchers—remarks, “They want to clean up and make Delhi pretty, so they’re grabbing the poor and the monkeys and kicking them out.”

The continuous displacement to urban peripheries compounds job vulnerability, reflecting a broader trend of labor contractualization. This system enables employers to reduce wage bills while rendering workers expendable, interchangeable, and easy to hire or fire. Throughout Eeb Allay Ooo!, supervisors at Anjani’s and his brother-in-law’s workplaces routinely dismiss grievances with retorts like “there’s no need to work” or “nobody’s forcing you,” remarking at the powerlessness of this arrangement.

Repelled to the Margins of the City

The vision to transform Delhi into a global metropolis has no room for monkeys or monkey-repellers. The presence of the monkey in its space hinders the city’s developmental aspirations, generates risks to public health and safety, and serves as a ringing reminder of its Global South status. The judicial and executive organs have synchronized their efforts to tackle the monkey nuisance and hasten urbanization. The Delhi High Court, for example, has issued several directions to civic bodies to formulate a plan to shift monkeys away from the city space.

While the New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) ordinarily responds to these orders with tepid solutions, its anxieties are heightened when faced with global events such as the G20 Summit in September 2023, since the appearance of monkeys amidst the classical arches and domes of Raisina Hill evoked Orientalist stereotypes about the city and contradicted its desire for a world-class appearance. Thus, hectic efforts to beautify the city ahead of the arrival of international bureaucrats involved a myriad of monkey-chasing techniques, including poster cut-outs of langurs.

Delhi’s pests are pushed away from the core, to the peripheries. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, the contractors are instructed to chase monkeys away from the locality of the Central Secretariat towards the northern suburbs in Shastri Nagar. Instead of resolving the issue to create an inclusive and liveable space, urban governance focuses on shifting the burden away from upscale neighborhoods.

In his 2015 book Rule By Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi, geographer Asher Ghertner introduces the practice of “rule by aesthetics” which attempts to impose a vain spatial discipline on the city’s people. By transferring the monkey menace to working-class neighborhoods, the municipal authorities can postpone the crisis and maintain the sanitized appearance of the administrative districts.

The spatial purification of the city center is not restricted to monkeys; it extends to the monkey-chasers. The omnipresence of monkeys in Delhi is partly owed to the numerous individuals who welcome them as incarnations of the Hindu monkey god Hanuman and feed them to receive divine blessing. The public approach to monkey troops is beset with contradictions; instead of being treated as trespassers, they are often received warmly or jovially. While the city has attempted to come to terms with its monkey population, it struggles to extend the same sympathy to the working poor who are deemed encroachers on its land and relegated to the slums.

Vats’ sardonic approach to this reality is depicted in the final scenes of Eeb Allay Ooo!, during which a monkey-repeller is lynched to death by a mob for using a slingshot to hit a monkey. The monkey has been incorporated into the city’s social fabric, embraced as an idiosyncrasy that animates its architecture and merits protection. However, the monkey-repellers are deprived of urban citizenship, caught in the contradictions of bourgeois environmentalism and exclusionary bureaucratism. They who make the city habitable are not allowed to inhabit it themselves.

The film captures the dialectic between the city and its inhabitants with an elegance and verve that confers a lasting relevance to the story. Weaving questions of existence and belonging with the humdrum of daily life, Vats fits Eeb Allay Ooo! in a genre of city films that evoke nostalgia, garner timeless appeal, and speak to the experiences of the working people.

The global city has been made on the backs of local labor, without accounting for their rights to public space. The quotidian forms of oppression and violence deployed by the city have pushed monkey-repellers into other professions in search of a more secure future. As most monkey-repellers leave Delhi under the swirl of powerful interests, we must confront the emerging crisis of social belongingness. If Yusuf and Gul Khan are evicted, who is the city for?

Urban sociologist Robert Park proclaims that the city is a method for man to remake the world he lives in, to his heart’s desire. Following his method, for the working people, dilli abhi door hai—Delhi is still far away.

Delhi is simultaneously everyone’s city and nobody’s city. It is home to the highest number of migrant workers in India, with 21 percent of its population composed of external migrants, predominantly from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. These communities have created cultural enclaves scattered throughout the city, making Delhi a diverse yet ambiguous socio-cultural milieu.

Prateek Vats’ 2019 film, Eeb Allay Ooo!, explores the life of Anjani Prasad (Shardul Bharadwaj), a monkey-repeller in New Delhi, and traces the practice of monkey chasing, a community-driven craft originating from contractual laborers in the capital. The filmmaker draws from his experiences as a second-generation Bihari migrant in Delhi, and attempts to make sense of home and belonging. Being a resident and student in Delhi, Vats was motivated to make his debut feature film on the question of monkey-repellers’ response to the world around them, which, he says, “thrives on depriving its people of their dignity.”

The official poster of Eeb Allay Ooo! captivates its viewers through an orientalized image of the Karnatic langur, showing Anjani having painted himself black and wearing a sharp, white, furry costume to mimic a langur. This get-up serves a dual purpose: it is intended to scare away monkeys, while simultaneously providing an exotic, orientalist spectacle, particularly for tourists. But the film ultimately tells the tale of those who make the city liveable but cannot live in it themselves. It maps the relationship between Delhi, the heart of Indian democracy, and the monkey menace, to uncover the forgotten actors of the story—the monkey chasers.

The peculiar case of macaque monkeys in Delhi reflects the tussle between fascination and repulsion, sanctity, and rambunctiousness. Driven from their natural habitats in search of food and shelter, these monkeys have migrated to urban areas, mirroring the broader patterns of human migration. As Delhi evolves into a sanitized hub of modernity and urban governance, monkeys— as perceived pests— have become an inconvenient and often embarrassing issue, largely absent from the global G20-esque headlines. This migration has also led to monkey-repellers—individuals or services, hired to manage and remove the animals from urban spaces using a combination of mimicry and langur costumes. Until recently, the repellers coexisted harmoniously with langurs— considered natural predators of macaque monkeys— and even relied on them as part of their trade practices. After an environmentalist ban was imposed on using langurs for commercial purposes, the monkey-repellers were forced to resort to mimicking the calls of their erstwhile partners to scare the macaque prey away.

Their skill of mimicking predatory animals has a distinguished provenance, evolved through their everyday interactions. However, these techniques are being diluted, their creators displaced, and their profits increasingly reaped by contractors, technocrats, and even AI policy-makers. The dichotomy of the monkey and the man is fleshed out amidst the rise of conservative values, leading the former, as deities of Delhi, to have firmer rights to the city than the latter.

While the state has been hesitant to use stringent measures to remove monkeys due to pressure from environmentalists, it had no qualms about leaving its migrant population starved and destitute amid a global pandemic. Vats captures these contradictions with an astute elegance. Beneath its quirky facade, Eeb Allay Ooo! tells a poignant story of a powerless man in a powerful place.

The Performance of Monkey-Repelling

The practice of monkey capture is not a mere caper or a product of trivial tricks; rather, its history reflects a profound understanding of simian behavior, empathy, and warmth, which challenges prevailing misconceptions about the wild. Consider, for instance, the case of Gul Khan, a professional monkey chaser in New Delhi for over three decades. Khan’s expertise is grounded in his relational understanding of langurs.

His family lived with the langurs, cared for them, and even shared meals with them as though they were household members, and their deep understanding of the langurs profoundly informs their trade. The mirroring of their voice, gestures, and emotions is essential to their partnership.

The craft of monkey chasing traces its lineage to the Kalandar tradition—a community of performers and dancers who historically entertained the urban populace. Khan notes monkey chasers employ a distinct language—he frequently produces high-pitched, sharp sounds to deter monkeys. “Triooo! Oooo!” he exclaims, mimicking the langur’s call, causing the monkeys to retreat.

Consequently, the words employed by Khan, and by Anjani in Eeb Allay Ooo!, are neither erratic nor random; they are deeply embedded in a history of human experience, signifying a covenant between humans and non-humans. These oral calisthenics—diction, cadence, and tone—represent a labor of love, honed through consistent practice.

However, recent state policies have systematically eroded this trade, precipitating its decline. Many Kalandar families, including Gul Khan’s, adapted to monkey chasing as a means of survival—only to witness their livelihood appropriated by corporate and state actors in yet another painful reminder of deliberate disenfranchisement.

The pervasive start-up ecosystem, for example, has dipped its toes in the monkey business. Bengaluru-based company Katidhan, platformed on Shark Tank India, recently introduced an advanced sound-programming device to detect and deter monkeys. The start-up claims to be easing farmers’ misery, although the device carries a hefty price tag of $130 and relies on sonic strategies created by contractual migrant workers. In 2019, Microsoft publicly introduced an AI project that had been funded to build a large geolocation database of Delhi’s monkeys and allow animal control officers to identify and sterilize them.

For experienced monkey-chasers like Gul Khan, however, the personalities and politics of these monkey troops have been inscribed onto their memories. Years of working in the profession have allowed them to develop familiarity with the distinct troops that reside in each neighborhood, and the diverse approaches the monkeys adopt in response to the repellers. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani learns to identify the alpha male head of each troop and recognize the distinct temperaments of the monkeys that frequent Lutyens’ Delhi. The film’s title thus serves as both an homage to the origins of this art and a critique of its increasingly co-opted etymology.

The practice of repelling shapes the geography of urban life, influencing domestic economies, social life, and beyond. Many monkey chasers, such as Khan, live close to the langurs they work with and are compensated with a daily wage of approximately INR 643 (USD 7.62) for eight hours of work. After a 2021 government decision banned the use of langurs themselves, Khan and others had to let go of their langur companions and develop an entirely new mimicry skill to perform their job. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani is chastised for his newfangled chasing methods such as cardboard cut-outs or costumes resembling langurs.

The creativity of both reel and real monkey-repellers is met with apathy or disdain, while the state endorses the same strategies under the guise of research and innovation. Owing to their class and caste identities, monkey-chasers are never approached to contribute to the creation of scientific knowledge regarding their work. Despite numerous bureaucratic measures, the city’s municipal authorities have been unwilling to recognize and legitimize the status of monkey-repellers.

As a result, they often reside in informal settlements and bastis, distanced from the Lutyens belt. Efforts to separate the artisan from the art are an insult to the integrity of their craft and the social contexts underpinning its creation. The precarity of these migrant workers of Delhi is invisibilized in favor of profits reaped using the techniques of their labor. The last census was conducted more than 13 years ago, in 2011. The dearth of accurate data on the conditions of migrant laborers discloses the state’s apathy toward informal workers and its rapid retreat from welfare services.

The Fragility of Informal Labor

The informal sector in Delhi constitutes the city’s backbone. Eeb Allay Ooo! interrogates the question of migrant labor—who performs it, for whose benefit, and who holds dominion over it. The one-bedroom house shared by Anjani, his sister (Nutan Sinha), and his brother-in-law (Shashi Bhushan) becomes a microcosm of this urban economy. Each of them is an informal worker, entangled in precarious employment marked by minimal job security, unsustainable working hours, and an absence of healthcare—trapping them in a cycle of persistent poverty.

As the film slowly peels its onion, we are confronted with the fragility of informal labor, even when it serves the highest echelons of power, such as bureaucrats and parliamentarians. In one scene, Anjani meekly responds to his sister that he does not hold a sarkari (government) job but a sarkari-jaisi naukri (appears like a government job), underscoring how proximity to privilege has failed to translate into benefits or social security. Residents of impoverished settlements, often excluded from formal welfare frameworks, must find dignity through livelihood diversification and their limited access to social capital.

In Eeb Allay Ooo!, Anjani’s employment in Lutyens becomes a point of pride for his sister, who shares this fact with her doctor at the government clinic. Anjani’s access to social capital also creates opportunities for supplementary income, as he poses for tourists and foreigners who photograph him in his langur costume. The oddness of his costume makes him look out of place, exotic, and the perfect spectacle for a tourist seeking a quirky India photo. He uses this oddity and ingenuity to his advantage by charging the tourists a fee.

However, this act of ingenuity results in his dismissal when a religious, Hanuman-devout councilor lodges a complaint following the circulation of his viral videos on social media. Thus, one of the rare moments of laughter in Eeb Allay Ooo!—Anjani becoming “viral” in his get-up—comes to a cruel and abrupt end. Anjani losing his job highlights the undemocratic practices that underpin informal and gig work. It underscores the lack of agency or influence workers have over their methods of labor, where any effort to improve the indignities of their conditions is viewed as insubordination, and punished.

Like Anjani, countless informal and essential workers shoulder dangerous work to make the city habitable, and aspirational. Yet they remain excluded from its promises, unable to inhabit, or thrive, within it. These divisions and displacement ripple outward, forcing thousands of migrants to relocate far from the city core. In an ethnographic study on monkey capture in Delhi by Ajay Gandhi, Yusuf, a resident of East Delhi’s slums—home to many monkey catchers—remarks, “They want to clean up and make Delhi pretty, so they’re grabbing the poor and the monkeys and kicking them out.”

The continuous displacement to urban peripheries compounds job vulnerability, reflecting a broader trend of labor contractualization. This system enables employers to reduce wage bills while rendering workers expendable, interchangeable, and easy to hire or fire. Throughout Eeb Allay Ooo!, supervisors at Anjani’s and his brother-in-law’s workplaces routinely dismiss grievances with retorts like “there’s no need to work” or “nobody’s forcing you,” remarking at the powerlessness of this arrangement.

Repelled to the Margins of the City

The vision to transform Delhi into a global metropolis has no room for monkeys or monkey-repellers. The presence of the monkey in its space hinders the city’s developmental aspirations, generates risks to public health and safety, and serves as a ringing reminder of its Global South status. The judicial and executive organs have synchronized their efforts to tackle the monkey nuisance and hasten urbanization. The Delhi High Court, for example, has issued several directions to civic bodies to formulate a plan to shift monkeys away from the city space.

While the New Delhi Municipal Corporation (NDMC) ordinarily responds to these orders with tepid solutions, its anxieties are heightened when faced with global events such as the G20 Summit in September 2023, since the appearance of monkeys amidst the classical arches and domes of Raisina Hill evoked Orientalist stereotypes about the city and contradicted its desire for a world-class appearance. Thus, hectic efforts to beautify the city ahead of the arrival of international bureaucrats involved a myriad of monkey-chasing techniques, including poster cut-outs of langurs.

Delhi’s pests are pushed away from the core, to the peripheries. In Eeb Allay Ooo!, the contractors are instructed to chase monkeys away from the locality of the Central Secretariat towards the northern suburbs in Shastri Nagar. Instead of resolving the issue to create an inclusive and liveable space, urban governance focuses on shifting the burden away from upscale neighborhoods.

In his 2015 book Rule By Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi, geographer Asher Ghertner introduces the practice of “rule by aesthetics” which attempts to impose a vain spatial discipline on the city’s people. By transferring the monkey menace to working-class neighborhoods, the municipal authorities can postpone the crisis and maintain the sanitized appearance of the administrative districts.

The spatial purification of the city center is not restricted to monkeys; it extends to the monkey-chasers. The omnipresence of monkeys in Delhi is partly owed to the numerous individuals who welcome them as incarnations of the Hindu monkey god Hanuman and feed them to receive divine blessing. The public approach to monkey troops is beset with contradictions; instead of being treated as trespassers, they are often received warmly or jovially. While the city has attempted to come to terms with its monkey population, it struggles to extend the same sympathy to the working poor who are deemed encroachers on its land and relegated to the slums.

Vats’ sardonic approach to this reality is depicted in the final scenes of Eeb Allay Ooo!, during which a monkey-repeller is lynched to death by a mob for using a slingshot to hit a monkey. The monkey has been incorporated into the city’s social fabric, embraced as an idiosyncrasy that animates its architecture and merits protection. However, the monkey-repellers are deprived of urban citizenship, caught in the contradictions of bourgeois environmentalism and exclusionary bureaucratism. They who make the city habitable are not allowed to inhabit it themselves.

The film captures the dialectic between the city and its inhabitants with an elegance and verve that confers a lasting relevance to the story. Weaving questions of existence and belonging with the humdrum of daily life, Vats fits Eeb Allay Ooo! in a genre of city films that evoke nostalgia, garner timeless appeal, and speak to the experiences of the working people.

The global city has been made on the backs of local labor, without accounting for their rights to public space. The quotidian forms of oppression and violence deployed by the city have pushed monkey-repellers into other professions in search of a more secure future. As most monkey-repellers leave Delhi under the swirl of powerful interests, we must confront the emerging crisis of social belongingness. If Yusuf and Gul Khan are evicted, who is the city for?

Urban sociologist Robert Park proclaims that the city is a method for man to remake the world he lives in, to his heart’s desire. Following his method, for the working people, dilli abhi door hai—Delhi is still far away.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.