Conjuring the BK16 Myth: How the Elgar Parishad case rests on fiction and deception

This is the second report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part three here.

Three months after a Hindutva mob attacked a peaceful gathering of Dalit-Bahujan men, women, and children, a cabal from the Pune Urban Police mounted a bizarre prosecution, holding 16 eminent human rights defenders (HRDs) responsible for the Elgar Parishad, an anti-caste event held in the city, a day before. The infamous case has, however, come to draw its name less from the event, and more from the calamitous gathering that assembled on both sides of the river Bhima, on 1st January 2018, to pay homage to an obelisk-shaped martyrs’ column, at Perne Phata, opposite the village of Koregaon. In the months that followed, the HRDs were imprisoned in waves of arrests across the country, with no evidence so far linking them to the mob violence.

Every year, on the 1st of January, as reported in the first part of this series, Dalit-Bahujans from all over Maharashtra, and beyond, gather around Pune’s Bhima Koregaon to visit the martyr’s obelisk they refer to as Vijay Stambh. The memorial commemorates their ancestors’ valour displayed in the day-long deadly battle at Koregaon Bhima in 1818. A motley battalion of around 800 men—predominantly from the oppressed Dalit and Bahujan castes—had forced the retreat of a 30,000-strong army, led by the Brahminical Peshwa regime. For nearly four decades, the annual commemoration at Koregaon Bhima had been an unimpeded affair, except for 2018—the bicentennial anniversary of the eponymous battle.

The mob that blazed through the hallowed grounds of Koregaon-Bhima carried garish saffron flags and wore thumb-smeared tilaks on their foreheads, symbolising their aggressive stance within western Maharashtra’s Hindutva fold of rightist politics. In wanton displays of violence, the mob spared no one—not even children and the elderly—assaulting them under the gaze of well-armed contingents of the Pune Rural Police. Yet, it was 16 lawyers, social activists and academics distinctly sympathetic to the cause of those waving the blue and penta-coloured Panchsheel flags of Dalit-Buddhists—many of whom were not even based out of Maharashtra—whose doors the police knocked on.

These 16 individuals—who have been given the moniker of BK16—soon became a tendentious entity. Sixteen pen-holding, paper-waving men and women, somehow were deemed an indomitable threat to India’s national security. But how these arrests—so preposterous on paper they seem satirical—would come to stand the test of criminal cognisance for seven long years is a question that ought to prick the judicial conscience of a professed democratic nation. The last verdict on the matter may potentially turn the Indian throne into a seat of discomforting thorns.

The Polis Project sifted through countless documents in an attempt to unravel what really happened—to fathom the depth of the dice that was cast. These included the chargesheets and supporting documents filed by the Pune Police and the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in the case; numerous petitions and orders at both levels of the higher judiciary; and perhaps most crucially, the glimmering armour of hope in the legal defence of the BK16—the independent cyber forensic evidence examined by reputed international laboratories. There were several credible international cyber forensic probes into clones of the electronic devices that are said to have belonged to the accused, all of which point to the unprecedented scale and nature of the fabrication of evidence. The case holds global appeal as a creative institutional work of dark, anfractuous fiction, whose roots go way back to the 2013-14 Gadchiroli arrests.

The Gadchiroli prequel and the bogey of “urban Naxalism”

In the second half of August 2013, the Gadchiroli Police abducted a young foreign language student of Jawaharlal Nehru University from Ballarshah Railway Junction, in eastern Maharashtra, some 700 km away from Bhima Koregaon. He was not produced before any court for three full days, in violation of the Indian criminal procedure. Even after his formal arrest and court production, he was tortured in police custody for three more weeks. Two others—Adivasi residents of a Gadchiroli village—were meanwhile brutalised and compelled, under duress, to implicate themselves and the JNU student, through tutored magisterial confessions. The confessions were retracted soon after, of course, once they gathered the courage to do so in jail. Yet, their confessions became one of the main grounds for the trial court to deliver a guilty verdict in the case.

Hem Mishra, the JNU student, was accused of being a courier for the late GN Saibaba, an assistant professor of English in Delhi University, on behalf of an alleged urban frontal organisation of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist), named Revolutionary Democratic Front (RDF). The claim was that Mishra had been deputed to deliver an RDF memory card containing some incriminating information to an underground Maoist leader named Narmadakka, who subsequently passed away in police custody before ever being charged in the Gadchiroli trial. Two others were also abducted in the same case from Raipur in September, and Saibaba was arrested the following May. The conviction of the six in an expeditious trial at Gadchiroli Sessions Court, on 7 March 2017, triggered an outcry across the country and overseas.

In his 824-page conviction judgment, the sessions judge Suryakant Shinde, coined the category of “urban Naxals,” referring to people—like Saibaba and his co-accused—who stood in the way of modern “developmental” projects. The judge believed this to be the only legitimate way to raise the living standard and well-being of underprivileged people. Within months, the ultra-right propagandist Vivek Agnihotri used it in an essay for Swarajya, a right-wing periodical, and later for an eponymous book. Tainting supporters of the radical left with this term soon became commonplace in India’s public discourse.

In late January 2018, emboldened by the Gadchiroli verdict and the Bombay High Court’s rejection of post-conviction bail, the same police team launched a nationwide witch-hunt of the persons who would eventually become the BK16. Unfortunately for that prematurely elated section of Maharashtra Police, on 5 March 2024, the Bombay High Court’s Nagpur Bench overruled the contentious sessions judgment. For those six years, however, the rolling stone that was the Elgar Parishad conspiracy case remained in motion, picking up more and more HRDs as it bulldozed through the criminal justice system.

In fact, another bench of the same high court had discharged all six Gadchiroli “urban Naxals” back in October 2022, because the governmental sanction for their prosecution was invalid, which invalidated the entire sessions trial. But the Supreme Court stayed the judgment the very next day, and set it aside six months later, remanding it back to be heard afresh. It took another year for the judicial confirmation that the spectre of “urban Naxalism” was just a myth conjured out of thin air. In a report on the October 2022 discharge, The Wire pointed to the connections between the Gadchiroli and Elgar Parishad cases:

After Saibaba’s conviction, his lawyer in the lower court, Surendra Gadling; his colleague Hany Babu; and his close friend Rona Wilson were also arrested in years to come under the UAPA charges. While Gadling fought his case in court, Babu and Wilson had run a campaign for his release. All three are named as prime accused in the Elgar Parishad case of 2018. Babu’s wife and Delhi University professor Jenny Rowena said, (she is now) very hopeful. ‘After all, the Elgar Parishad case was largely dependent on Saibaba’s case. Saibaba’s acquittal will help us in proving the innocence of all those booked in the Elgar Parishad case,’ Rowena told The Wire.

Gadchiroli sets a precedent for the Elgar Parishad case

In its March 2024 acquittal judgment, after long years of debilitating anxiety and anguish, the Bombay High Court delivered justice, with an illustrative verdict on the applicability of the dreaded Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Despite the UAPA’s severe constraints and departures from usual criminal procedure—including a presumption of guilt—the judgment demonstrated at length the numerous procedural, evidentiary and substantive violations committed by the police in applying the anti-terror law. The court clarified that the presumption of guilt would not kick in if the concerned persons had not actually committed an offence in the category of terrorist acts, as defined under the UAPA.

It emerged from the rulings that mere allegations of unlawful activity amounting to a generic kind of support to an alleged terrorist organisation would not attract the grave charges related to terrorist acts. Such charges range from “terrorist conspiracy,” “being member of a terrorist organisation indulging in terrorist activities,” “support to terrorist activities of a banned organisation,” to even “professing to be member of a terrorist organisation.” The UAPA’s special procedures for arrest and seizure were also expounded for the first time, in terms that would invalidate most of the tenuous procedures followed by the same police dispensation in the Elgar Parishad case.

Laying down the law on how to ensure a secure electronic record—to be considered non-tampered evidence—the high court pointed out the need to record hash values of the data in electronic storage devices at the very time of seizure. Hash values are unique alpha-numerical values that represent the contents of a file. The law in this regard would have to apply to trials conducted in cases, like the Elgar Parishad case, involving seized electronic evidence. Hash values recorded subsequently at state forensic labs—as conducted by the Elgar Parishad prosecution—cannot prove that any electronic data seized is secure and free of any post-seizure manipulation.

Since January 2020, when the NIA took over the Elgar Parishad case from the Pune Police, it continued with more arrests, over and above the nine HRDs already put behind bars by the Pune Police. One of those the NIA targeted was Stan Swamy, a former Jesuit priest tribal activist, who tragically died in custody. However, after the Gadchiroli acquittal judgment, in Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others vs State of Maharashtra, even the NIA has turned demure, albeit selectively. It conceded bails to at least three of the Elgar Parishad accused, most recently to Sudhir Dhawale and Rona Wilson, whose counsels were assured that the bail would not be appealed against at the Supreme Court.

This is in stark contrast to the case of Mahesh Raut, a former grantee of the prestigious Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellowship at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Raut was granted bail by the Bombay High Court in September 2023, but the bail was stayed to allow the NIA to file an appeal. Since then, the Supreme Court has relentlessly extended the stay, while the police’s appeal against the bail still remains pending. Raut’s bail matter languishes at the Supreme Court along with the bail application of the advocate Surendra Gadling, whose foundational defence in the Gadchiroli case—until the end of 2017—played a key role in paving the way for the acquittal judgment.

At the time of writing, the NIA still continues to oppose Gadling’s bail, on some ground or the other, fuelling doubts over what particular grouse the state could have against the noted rights defender. Apart from Raut and Gadling, their co-accused Jyoti Jagtap, a cultural activist, is also concurrently seeking relief before the same Supreme Court bench.

Common threads between the Gadchiroli and Elgar Parishad arrests

It was not just Babu, Wilson and Gadling who were vocal and active in their opposition to the Gadchiroli convictions. Sudhir Dhawale, a radical Ambedkarite social activist, and his comrades from a caste-annihilation movement that was building up around the Kabir Kala Manch, were also involved in the growing protests against the incarcerations then. Today, Ramesh Gaichor, Sagar Gorkhe, and Jyoti Jagtap from the Kabir Kala Manch remain behind bars in the Elgar Parishad case.

Cut to the Commission of Inquiry probing the Koregaon-Bhima violence of 2018, examined in detail in the first part of this series, and we see the evidence on record demonstrating distinct similarities to the Gadchiroli case. For one, no involvement in the violence, much less in any terrorist act, could be inferred against any of the Elgar Parishad accused—the BK16.

Among the police officials who testified before the commission is Shivaji Pawar, the investigating officer in the Elgar Parishad case from January 2018 until the NIA took over in 2020, and to whose Zone I in Pune city the case was inexplicably transferred. On 28 February 2023, Pawar stated before the commission that, among the superior officers who guided him in that investigation, were the very same officers who conducted and guided the investigations into the Gadchiroli case.

One of Pawar’s guides was Suhas Bawche, a deputy commissioner who was not even responsible for Pawar’s jurisdiction in Pune, but for Zone II. Bawche was the deputy superintendent in Gadchiroli district and conducted the specious investigation from August 2013 onwards, and steered the prosecution in a trial that eventually failed to stand the test of law. It only resulted in the six defenders’ unwarranted incarceration over an average of about eight to nine years.

Another officer named by Pawar before the commission was Bawche’s guide and instructor in the Gadchiroli case: Ravindra Kadam, then a deputy inspector general, who subsequently became joint commissioner at Pune, and retired shortly thereafter. It needs only the joining of dots to realise how the very same officer trio went on to form a core of the cabal that tucked the feather of the Elgar Parishad case on the Pune Police’s cap.

A monstrous edifice for a case founded on clay

As detailed in the first part, Pawar was questioned multiple times during his cross-examination about any evidence regarding the involvement of anyone from the BK16, in the evidence of the violence extensively recorded before the commission. In defence, Pawar did not refer to anything on the commission record—which included scores of police reports and chargesheets encapsulating all the possible violence that occurred surrounding the bicentennial Bhima Koregaon commemoration. Instead, he repeatedly cited the Elgar Parishad chargesheets—comprising tens of thousands of pages of documents, not one of which contained even an iota of evidence to link the mob violence at Koregaon Bhima on 1 January 2018 with the Elgar Parishad of 31 December 2017.

Even Pawar’s own chargesheets–the final report of the investigation filed on 15 November 2018 and the first supplementary final report filed on 21 February 2019—as well as the second supplementary final report filed by the NIA on 9 October 2020, offer no cogent connection between the two events. The unusually voluminous material carries just two probable sources of incriminating evidence.

The first is a variety of documents—an incredulous genre of digital fiction, as we shall see in part three of this series—recovered from the electronic devices allegedly seized from the residences of the accused. The second source is the testimonies of half a dozen unknown individuals classified as “protected witnesses,” five of whose statements were also recorded before a judicial magistrate. While their identities remain undisclosed, their testimonies show that the crucial ones happen to be former Maoists who surrendered to the state, ostensibly on terms that would deem them as nothing but stock witnesses.

Even if seen without any discernment, the evidence at face value is at most suggestive of a keen interest in following some of the developments related to contemporary Maoist activities, but lacks any vital connection with any cogent offence. Most crucially, no terrorist act could possibly be alleged as committed, or even plotted in this case. The evidence holds no relevance to any role in the anti-Dalit mob violence at Koregaon Bhima, or for that matter, anything to do with any Dalit retaliation or chaos anywhere in the country either.

Instead, the investigators appear to have taken undue advantage of a lone procedural provision: Section 173 (8). This subsection of the Code of Criminal Procedure forms one of many easily abusable tools within criminal law, by effectively allowing investigating officers to continue their investigation into a case indefinitely, adding on as many layers of allegations as they may please. In UAPA cases, where the investigator cannot be a low-ranking officer, an otherwise competent officer trained to apply the technological skills involved in accessing digital data of suspects could have a lot of incriminating layers to deploy.

The prosecution has also been particularly tardy in complying—unless compelled by a legal challenge—with the procedural mandate of supplying all incriminating documents to the defence before a trial commences, under Section 207 of the Code. The prosecution has claimed a total of 363 witnesses during a high court hearing in January 2025, but the chargesheets only list 48 witnesses with statements actually recorded and annexed.

A genesis that may engender the nemesis

Since receiving copies of the first supplementary chargesheet in February 2019, the defendants and their counsels have been running from pillar to post—between the special NIA court and the Bombay High Court—for the prosecution’s documents arrayed against them. Only after all the documentary evidence, whether explicit or implicit, is provided to the defence team, would the case be able to enter unhindered into the trial stage.

To be sure, the NIA has so far not appeared to be in any great hurry to proceed to trial. The case has also faced a number of challenges from the defendants at the pre-trial stage, with multiple petitions pending at the high court for quashing the case against a few individual defendants, and most likely a few more for a discharge, even as the prosecution may prefer to expedite the framing of charges for a trial.

The case that was registered on 8 January, and became synonymous with the electrifying 31 December 2017 Elgar Parishad event, was curiously belated. Such a delay in filing a first information report could itself be a potential valid ground for a discerning court to reasonably doubt whether the allegations were an after-thought. Malice, as most judges would know, often begets delays in registering FIRs.

Until March 2018, the case carried minor charges, alleging incendiary speeches, recitation and singing, which were purported to have instigated the violence and chaos at Koregaon Bhima. But, as we have seen so far, the case since its genesis, could very well be looking at its nemesis.

The slim silhouette of the Gadchiroli acquittal in Mahesh Kariman Tirki portends an inevitable threat to the monstrous heap of chargesheet documents that the NIA has been entrusted to champion.

Spate of raids-seizures-arrests

On 17 April 2018, the Pune Police conducted the first wave of raids and seizures, without search warrants, which were actually denied twice, even after an in-camera hearing of Pawar’s second application for the same. The raids were conducted at the residences of multiple suspects, in the cities of Mumbai, Pune, Nagpur, and Delhi. The digital contents of the devices allegedly seized from Wilson and Gadling became the ground for the invocation of the UAPA in May that year. A second wave of raids and seizures followed, on 28 August, against at least six others in Hyderabad, Ranchi, Faridabad, Goa, Thane and once again Mumbai.

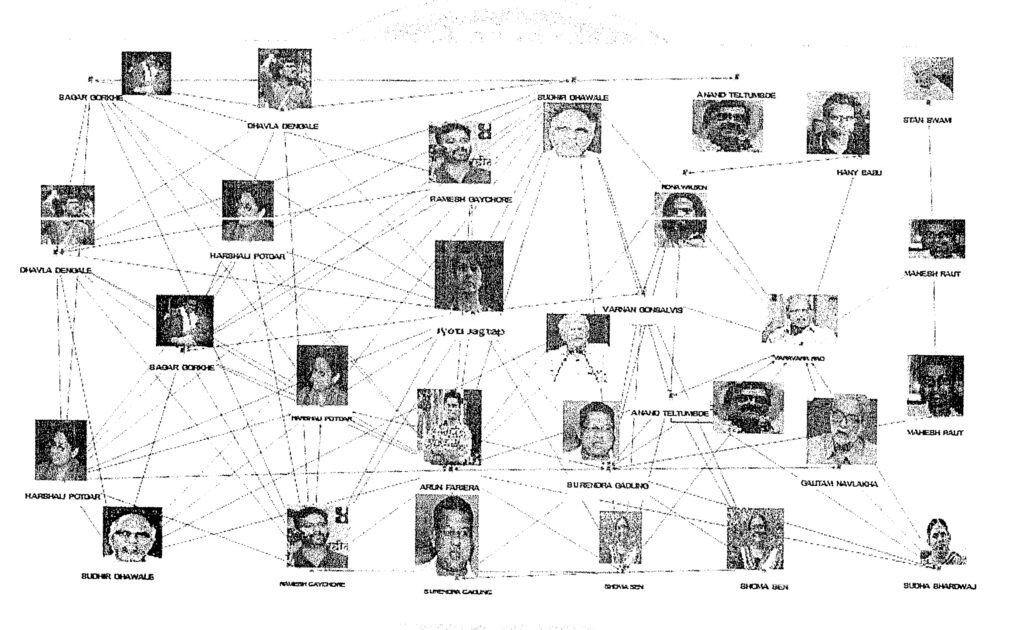

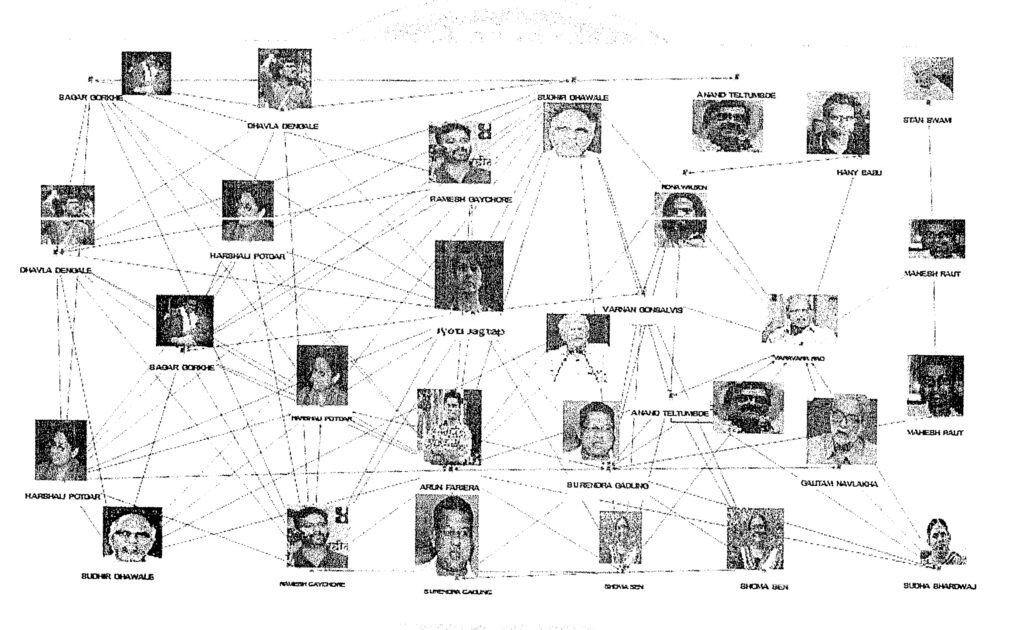

Both raid-and-seizure waves crested with concerted arrests. The first set took place on 6 June, of four persons first raided in April, and one more whose house was purportedly subjected to raid-and-seizures on the same day as her sudden arrest, though her arrest memo does not mention any seizure. They became the BK5:

1. Sudhir Dhawale;

2. Rona Wilson

3. Surendra Gadling

4. Shoma Sen

5. Mahesh Raut

Each of them well-known human-rights defenders who may have crossed paths over some cause or the other, such as Wilson and Gadling had over the state’s persecution of Saibaba. Naturally, then, there would be calls exchanged between two or more of them, which could be brought in as evidence of a fabricated conspiracy, without the voice recordings to alleviate the inevitable doubts. The court empowered with taking cognisance would not have bothered to see if the alleged call records carried any conversation records to help determine if there was really any incriminating evidence. The Pune Police cabal must have been unduly confident on account of just such a reading of the call records in the Gadchiroli case until the very end of trial.

The second set of arrests occurred simultaneously with raids and seizures on 28 August. Under the higher judiciary’s orders, the six HRDs were detained for months at their own houses, only to be thrown behind bars later—two of them on 26 October, another the next day on 27th, and the fourth on 17 November. That raised the number to nine. More raids and seizures followed in September 2019, followed by more arrests in July and October 2020, which made them the BK12:

6. Varavara Rao

7. Arun Ferreira

8. Vernon Gonsalves

9. Sudha Bharadwaj

10. Gautam Navlakha

11. Anand Teltumbde

12. Hany Babu.

The 2020 operations gathered new steam after the NIA took over the reins from the Pune Urban Police, which was red-flagged in the wake of a political regime change in Maharashtra in 2019. In September 2020, a fourth wave of arrests took place, this time targeting the core members of Kabir Kala Manch: Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor, and Jyoti Jagtap. The three members of the cultural collective were arrested on 7 and 8 September—all three of their homes had been raided and “evidence” from them seized, back in April 2018. At the time of publishing, all three remain in custody.

The last, but certainly not least, invidious infringement of fundamental freedoms took place a month later. Stan Swamy’s electronic devices had already been seized in two raids, on 12 June and 28 August 2019, by the Pune Police. The author of scores of insightful articles, including in support of the Pathalgadi movement for the self-determination of the Adivasis of Jharkhand, Swamy was an endearing father-figure to a large community of social and political activists. He was arrested on 8 October 2021. Less than a year later, he left behind a huge repository of memories for a truly democratic Indian society and polity, breathing his last in custody, in a private missionary hospital, where he was admitted too late. He was denied the requisite medical treatment for a critical diagnosis of Parkinson’s, which only an expedited release on bail could have ensured.

His arrest completed the construction of the BK16:

13. Sagar Gorkhe

14. Ramesh Gaichor

15. Jyoti Jagtap

16. Stan Swamy

Examining the “probative value of the evidence”

In December 2019, around the time when Sharad Pawar, the doyen of Maharashtra’s secular establishment politics, threw his weight behind the Elgar Parishad accused, The Caravan came out with a shocking forensic analysis of electronic evidence. Malware was detected in it! The report suggested that the seized device was distinctively compromised. As the matter was referred to the USA-based Arsenal Consulting, it triggered a spate of authentic reports of cognisance-worthy probes conducted by internationally renowned cyber forensic labs.

While vicissitudes in many a long-drawn snake-and-mongoose battles in courts continue, the “urban Naxal” conspiracy cases bereft of terrorist acts have lost much of their steam. In July 2023, the Supreme Court passed a crucial bail judgment, ordering the release of the Mumbai writer-activist duo Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira. The singular bail verdict enriched case law in favour of granting bail as many as five years into judicial custody without trial, despite grave charges under the UAPA as well as Indian Penal Code offences related to anti-state conspiracy, waging war and sedition.

The ground on which the court granted relief was an indisputable consideration of the prima facie probative value in the evidence, in a situation where the trial court seems in no position to conclude the trial anytime soon. The propensity of cases woven around the narrative of “urban Naxalism” to not generally constitute any commitment of acts that could fall under the purview of terrorist acts went a long way towards the Gadchiroli acquittals. Since then, either the snake has lost some of its sting or the mongoose its viciousness.

In April and May 2024, Shoma Sen and Gautam Navlakha secured bail at the Supreme Court, with the NIA-led prosecution unable to justify their prolonged incarceration without trial. In fact, the state even acknowledged that there was no need for Sen’s continued incarceration. Soon after, the Bombay High Court even heard arguments on petitions by Sen and Wilson—filed over three years earlier—to quash the case against them in its entirety. But just before the last winter vacation, the court stopped short of formally drawing conclusions.

The petitions, when seen together, present the case in all its dubious shades, and reach many notches above the minimal criterion for relief—the prima facie lack of probative value of the evidence. Whether the quashing petitions would be heard once again in the near future, by a new bench, and whether any verdict would be pronounced anytime soon, may be seen as the pegs of hope on which the future trajectory of the case hangs.

In Gonsalves and Ferreira’s bail judgment, the Supreme Court examined the probative value of the evidence sought to be relied upon by the prosecution. One by one, the court delved into every allegation and each provision under which the duo was charged, and held that the prosecution evidence was insufficient to establish, even prima facie, the guilt of the accused.

It noted that merely the possession of certain kinds of literature and documents did not prima facie amount to any offence as alleged by the prosecution. Further, the court stated that the allegation against Ferreira of handling finances also cannot be linked to any terrorist activity, on the basis of the evidence placed on record by the prosecution. The court also found that none of the letters and documents relied on by the prosecution, in an attempt to establish the duo’s connection with a terrorist organisation, were actually recovered from either’s possession. Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that the evidence of the prosecution had “weak probative value or quality,” with no prima facie case made out against the two, and directed their release.

Are there any immediate possibilities of release for the remaining BK-6?

The rationale of weak probative value or quality of the evidence could very well apply to the favour of the remaining six of the BK16—Raut, Jagtap, Gaichor, Gorkhe, Gadling and Babu. In fact, the Bombay High Court has already found the allegations against Raut too tenuous and granted him bail, though his release remains held up in the corridors of New Delhi. The allegations against Raut were similar to those against Gonsalves and Ferreira, vis-à-vis the handling of finances and the connection with the banned CPI (Maoist), which the police sought to establish through letters and documents not recovered from him. As such, Raut deserved relief at par, especially considering that he has been in prison since the first set of arrests, longer than Gonsalves and Ferriera.

Both Raut and Jagtap seem to have been deemed as having “Maoist links” on the basis of no credible evidence but hearsay. Raut’s charge relies on an activist-advocate in Mumbai who allegedly cited a newspaper report to claim that he may have recruited cadres for the Maoists. Against Jagtap, the prosecution has claimed that the Kabir Kala Manch is a frontal organisation for the Maoists, and a protected witness has purportedly stated that she had visited a training camp within eastern Maharashtra back in 2011. Clearly, there is no corroboration in the available evidence to substantiate these claims of the prosecution against Raut and Jagtap. Moreover, none of these allegations have any connection to anybody’s alleged role in the Elgar Parishad, or to anybody having possibly instigated the violence in Koregaon-Bhima.

The allegations against Jagtap are exactly identical to those against Gorkhe and Gaichor. What was most striking with regard to the three KKM activists is that the allegations in question do not constitute any offence specific to the Elgar Parishad case. Both allegations, that about the KKM being a frontal organisation—without any specific government notification or proven case thereof—and about the Maoist training camp, are actually part of an older case, from over a decade ago, registered by the state Anti-Terrorism Squad. All three were arrested in that case and released on bail despite those unsubstantiated claims. The same allegations, not even weighed in their previous trial as yet, are once again cited at the Supreme Court to deny Jagtap even the opportunity of an early bail hearing in her second case.

By the yardsticks set in the previous Elgar Parishad bail judgments of 2023 and 2024, equality before the law would mandate that all the four youngsters be released before long. But experiences at the Supreme Court have been far too varied in recent years for us to hope for consistent jurisprudence when it comes to the alleged younger supporters of the Maoist revolutionary movement. It may not be incorrect to suppose that the highest rung of the judiciary may be disinclined to look upon activists and researchers on the wrong side of law with the same empathy as with the old and the comfortably housed.

The two others still in prison are defendants accused of possessing incriminating documents allegedly recovered from their own electronic devices, just like the recently released Wilson: the advocate, Gadling, and the professor, Babu. But does the prosecution’s purported evidence against them establish the allegations? The astonishing acquiescence on the part of the state with respect to Wilson and Dhawale’s bail reflected the state’s assessment that a prima-facie reading of the available evidence, ahead of the trial, would establish its low probative value and poor quality.

In Babu’s case, it may suffice to cite accounts of the NIA’s interrogation prior to his arrest, as described by him to his family members. Babu was asked to explain how the incriminating files found in his laptop hard disk were neither indicated as created nor accessed by him, ever before the seizure of the laptop. What could he have answered? He had never seen those files, had no knowledge of them, and the NIA also seemed to believe so. The central agency had, after all, taken over the case at a very late stage, and might not have comprehended how the Pune Police proceeded despite such poor quality of incrimination. Yet, under Devendra Fadnavis as chief minister and home minister, the Maharashtra government allowed these police officials to carry out the arrests of those before Babu, based on weak evidence of suspicious origins. So, the NIA seemed to have blindly followed suit, arresting Babu too.

In fact, the NIA’s fear of a thorough prima facie probative evaluation of the evidence, when it refrained from opposing Wilson’s bail at the Bombay High Court, was not misplaced. “The credibility of the electronic evidence relied on by the prosecution has always been highly doubtful,” said a lawyer closely associated with the defence team. At no event could the electronic evidence sufficiently prove the guilt of the accused “beyond reasonable doubt,” the lawyer added.

First of all, at the time of seizure of the electronic devices, the investigation agency failed to generate hash values. The value changes with any change in the content of the file. The only set of hash values recorded in the charge-sheets are MD5 values. These have been recorded after the digital contents of the various seized devices were “acquired” on sterile hard disks at the respective state forensic science laboratories in Pune and Mumbai.

“Generating the hash value at the time of the seizure could ensure that the electronic device would not be tampered with after its seizure.” the lawyer opined. We found from our perusal of the case documents that no such process was undertaken by the investigating agency to “secure” the seized electronic devices, as required by the law governing the sanctity of digital evidence. The lawyer confirmed that thereby the credibility of all the electronic evidence in the Elgar Parishad case was seriously compromised. The lawyer added: “This fact becomes all the more disparaging for the prosecution in light of several reports published by esteemed international laboratories which have independently examined the electronic devices of the accused and come to the conclusion that the same electronic devices have been subjected to malware, since much prior to their seizure, unbeknownst to the accused themselves.”

These independent cyber forensic examinations, conducted at more than one credible international laboratory, have clearly indicated the hacking of various electronic devices seized from three of the defendants—Surendra Gadling, Rona Wilson, and Stan Swamy—in the case. These also indicated there were documents digitally delivered by a hacker into their devices. The earliest of these reports are very much part of the pending quashing petitions of Wilson, Sen and Swamy, with more such examinations, if not quashing petitions, still in the pipeline. Babu’s defence team chose not to comment on the matter.

As the only source of the alleged incriminating evidence to support the allegations, the electronic evidence simply cannot be considered secure electronic records. The digital part of the incriminating evidence would, therefore, potentially not be admissible in the evidence at all. That would deprive any incriminating witness statements of the essential aspect of corroboration. Hence, the probative value of the evidence envisaged in the huge volume of documents forming the Pune Police and NIA chargesheets virtually dwindles down to naught.

Given the overwhelming analysis revealing the implanting of fabricated documents in the seized electronic devices, one of the quashing petitions has, as a corrective measure, also sought the constitution of an independent Special Investigating Team. In fact, the previous state government in Maharashtra, led by the Maha Vikas Aghadi alliance forged by the veteran politician Sharad Pawar, had even announced that an SIT would investigate the alleged fake case against the BK16. The move was scuttled, in January 2020, when the union home ministry handed over the investigation to the NIA, making no bones about pre-empting any such remedial measure.

Following the elections in November 2024, the BJP returned to power with Devendra Fadnavis as chief minister, under whose previous tenure, the Koregaon Bhima violence and Elgar Parishad event cases as well as the commission proceedings took their current shape. While Sharad Pawar and his allies have been forced into the opposition benches, India’s independent judiciary would now be put to test on whether the ongoing travesty could be brought to an early end with the required truth-seeking exercise.

This is the second report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part three here.

Conjuring the BK16 Myth: How the Elgar Parishad case rests on fiction and deception

Three months after a Hindutva mob attacked a peaceful gathering of Dalit-Bahujan men, women, and children, a cabal from the Pune Urban Police mounted a bizarre prosecution, holding 16 eminent human rights defenders (HRDs) responsible for the Elgar Parishad, an anti-caste event held in the city, a day before. The infamous case has, however, come to draw its name less from the event, and more from the calamitous gathering that assembled on both sides of the river Bhima, on 1st January 2018, to pay homage to an obelisk-shaped martyrs’ column, at Perne Phata, opposite the village of Koregaon. In the months that followed, the HRDs were imprisoned in waves of arrests across the country, with no evidence so far linking them to the mob violence.

Every year, on the 1st of January, as reported in the first part of this series, Dalit-Bahujans from all over Maharashtra, and beyond, gather around Pune’s Bhima Koregaon to visit the martyr’s obelisk they refer to as Vijay Stambh. The memorial commemorates their ancestors’ valour displayed in the day-long deadly battle at Koregaon Bhima in 1818. A motley battalion of around 800 men—predominantly from the oppressed Dalit and Bahujan castes—had forced the retreat of a 30,000-strong army, led by the Brahminical Peshwa regime. For nearly four decades, the annual commemoration at Koregaon Bhima had been an unimpeded affair, except for 2018—the bicentennial anniversary of the eponymous battle.

The mob that blazed through the hallowed grounds of Koregaon-Bhima carried garish saffron flags and wore thumb-smeared tilaks on their foreheads, symbolising their aggressive stance within western Maharashtra’s Hindutva fold of rightist politics. In wanton displays of violence, the mob spared no one—not even children and the elderly—assaulting them under the gaze of well-armed contingents of the Pune Rural Police. Yet, it was 16 lawyers, social activists and academics distinctly sympathetic to the cause of those waving the blue and penta-coloured Panchsheel flags of Dalit-Buddhists—many of whom were not even based out of Maharashtra—whose doors the police knocked on.

These 16 individuals—who have been given the moniker of BK16—soon became a tendentious entity. Sixteen pen-holding, paper-waving men and women, somehow were deemed an indomitable threat to India’s national security. But how these arrests—so preposterous on paper they seem satirical—would come to stand the test of criminal cognisance for seven long years is a question that ought to prick the judicial conscience of a professed democratic nation. The last verdict on the matter may potentially turn the Indian throne into a seat of discomforting thorns.

The Polis Project sifted through countless documents in an attempt to unravel what really happened—to fathom the depth of the dice that was cast. These included the chargesheets and supporting documents filed by the Pune Police and the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in the case; numerous petitions and orders at both levels of the higher judiciary; and perhaps most crucially, the glimmering armour of hope in the legal defence of the BK16—the independent cyber forensic evidence examined by reputed international laboratories. There were several credible international cyber forensic probes into clones of the electronic devices that are said to have belonged to the accused, all of which point to the unprecedented scale and nature of the fabrication of evidence. The case holds global appeal as a creative institutional work of dark, anfractuous fiction, whose roots go way back to the 2013-14 Gadchiroli arrests.

The Gadchiroli prequel and the bogey of “urban Naxalism”

In the second half of August 2013, the Gadchiroli Police abducted a young foreign language student of Jawaharlal Nehru University from Ballarshah Railway Junction, in eastern Maharashtra, some 700 km away from Bhima Koregaon. He was not produced before any court for three full days, in violation of the Indian criminal procedure. Even after his formal arrest and court production, he was tortured in police custody for three more weeks. Two others—Adivasi residents of a Gadchiroli village—were meanwhile brutalised and compelled, under duress, to implicate themselves and the JNU student, through tutored magisterial confessions. The confessions were retracted soon after, of course, once they gathered the courage to do so in jail. Yet, their confessions became one of the main grounds for the trial court to deliver a guilty verdict in the case.

Hem Mishra, the JNU student, was accused of being a courier for the late GN Saibaba, an assistant professor of English in Delhi University, on behalf of an alleged urban frontal organisation of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist), named Revolutionary Democratic Front (RDF). The claim was that Mishra had been deputed to deliver an RDF memory card containing some incriminating information to an underground Maoist leader named Narmadakka, who subsequently passed away in police custody before ever being charged in the Gadchiroli trial. Two others were also abducted in the same case from Raipur in September, and Saibaba was arrested the following May. The conviction of the six in an expeditious trial at Gadchiroli Sessions Court, on 7 March 2017, triggered an outcry across the country and overseas.

In his 824-page conviction judgment, the sessions judge Suryakant Shinde, coined the category of “urban Naxals,” referring to people—like Saibaba and his co-accused—who stood in the way of modern “developmental” projects. The judge believed this to be the only legitimate way to raise the living standard and well-being of underprivileged people. Within months, the ultra-right propagandist Vivek Agnihotri used it in an essay for Swarajya, a right-wing periodical, and later for an eponymous book. Tainting supporters of the radical left with this term soon became commonplace in India’s public discourse.

In late January 2018, emboldened by the Gadchiroli verdict and the Bombay High Court’s rejection of post-conviction bail, the same police team launched a nationwide witch-hunt of the persons who would eventually become the BK16. Unfortunately for that prematurely elated section of Maharashtra Police, on 5 March 2024, the Bombay High Court’s Nagpur Bench overruled the contentious sessions judgment. For those six years, however, the rolling stone that was the Elgar Parishad conspiracy case remained in motion, picking up more and more HRDs as it bulldozed through the criminal justice system.

In fact, another bench of the same high court had discharged all six Gadchiroli “urban Naxals” back in October 2022, because the governmental sanction for their prosecution was invalid, which invalidated the entire sessions trial. But the Supreme Court stayed the judgment the very next day, and set it aside six months later, remanding it back to be heard afresh. It took another year for the judicial confirmation that the spectre of “urban Naxalism” was just a myth conjured out of thin air. In a report on the October 2022 discharge, The Wire pointed to the connections between the Gadchiroli and Elgar Parishad cases:

After Saibaba’s conviction, his lawyer in the lower court, Surendra Gadling; his colleague Hany Babu; and his close friend Rona Wilson were also arrested in years to come under the UAPA charges. While Gadling fought his case in court, Babu and Wilson had run a campaign for his release. All three are named as prime accused in the Elgar Parishad case of 2018. Babu’s wife and Delhi University professor Jenny Rowena said, (she is now) very hopeful. ‘After all, the Elgar Parishad case was largely dependent on Saibaba’s case. Saibaba’s acquittal will help us in proving the innocence of all those booked in the Elgar Parishad case,’ Rowena told The Wire.

Gadchiroli sets a precedent for the Elgar Parishad case

In its March 2024 acquittal judgment, after long years of debilitating anxiety and anguish, the Bombay High Court delivered justice, with an illustrative verdict on the applicability of the dreaded Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Despite the UAPA’s severe constraints and departures from usual criminal procedure—including a presumption of guilt—the judgment demonstrated at length the numerous procedural, evidentiary and substantive violations committed by the police in applying the anti-terror law. The court clarified that the presumption of guilt would not kick in if the concerned persons had not actually committed an offence in the category of terrorist acts, as defined under the UAPA.

It emerged from the rulings that mere allegations of unlawful activity amounting to a generic kind of support to an alleged terrorist organisation would not attract the grave charges related to terrorist acts. Such charges range from “terrorist conspiracy,” “being member of a terrorist organisation indulging in terrorist activities,” “support to terrorist activities of a banned organisation,” to even “professing to be member of a terrorist organisation.” The UAPA’s special procedures for arrest and seizure were also expounded for the first time, in terms that would invalidate most of the tenuous procedures followed by the same police dispensation in the Elgar Parishad case.

Laying down the law on how to ensure a secure electronic record—to be considered non-tampered evidence—the high court pointed out the need to record hash values of the data in electronic storage devices at the very time of seizure. Hash values are unique alpha-numerical values that represent the contents of a file. The law in this regard would have to apply to trials conducted in cases, like the Elgar Parishad case, involving seized electronic evidence. Hash values recorded subsequently at state forensic labs—as conducted by the Elgar Parishad prosecution—cannot prove that any electronic data seized is secure and free of any post-seizure manipulation.

Since January 2020, when the NIA took over the Elgar Parishad case from the Pune Police, it continued with more arrests, over and above the nine HRDs already put behind bars by the Pune Police. One of those the NIA targeted was Stan Swamy, a former Jesuit priest tribal activist, who tragically died in custody. However, after the Gadchiroli acquittal judgment, in Mahesh Kariman Tirki and others vs State of Maharashtra, even the NIA has turned demure, albeit selectively. It conceded bails to at least three of the Elgar Parishad accused, most recently to Sudhir Dhawale and Rona Wilson, whose counsels were assured that the bail would not be appealed against at the Supreme Court.

This is in stark contrast to the case of Mahesh Raut, a former grantee of the prestigious Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellowship at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Raut was granted bail by the Bombay High Court in September 2023, but the bail was stayed to allow the NIA to file an appeal. Since then, the Supreme Court has relentlessly extended the stay, while the police’s appeal against the bail still remains pending. Raut’s bail matter languishes at the Supreme Court along with the bail application of the advocate Surendra Gadling, whose foundational defence in the Gadchiroli case—until the end of 2017—played a key role in paving the way for the acquittal judgment.

At the time of writing, the NIA still continues to oppose Gadling’s bail, on some ground or the other, fuelling doubts over what particular grouse the state could have against the noted rights defender. Apart from Raut and Gadling, their co-accused Jyoti Jagtap, a cultural activist, is also concurrently seeking relief before the same Supreme Court bench.

Common threads between the Gadchiroli and Elgar Parishad arrests

It was not just Babu, Wilson and Gadling who were vocal and active in their opposition to the Gadchiroli convictions. Sudhir Dhawale, a radical Ambedkarite social activist, and his comrades from a caste-annihilation movement that was building up around the Kabir Kala Manch, were also involved in the growing protests against the incarcerations then. Today, Ramesh Gaichor, Sagar Gorkhe, and Jyoti Jagtap from the Kabir Kala Manch remain behind bars in the Elgar Parishad case.

Cut to the Commission of Inquiry probing the Koregaon-Bhima violence of 2018, examined in detail in the first part of this series, and we see the evidence on record demonstrating distinct similarities to the Gadchiroli case. For one, no involvement in the violence, much less in any terrorist act, could be inferred against any of the Elgar Parishad accused—the BK16.

Among the police officials who testified before the commission is Shivaji Pawar, the investigating officer in the Elgar Parishad case from January 2018 until the NIA took over in 2020, and to whose Zone I in Pune city the case was inexplicably transferred. On 28 February 2023, Pawar stated before the commission that, among the superior officers who guided him in that investigation, were the very same officers who conducted and guided the investigations into the Gadchiroli case.

One of Pawar’s guides was Suhas Bawche, a deputy commissioner who was not even responsible for Pawar’s jurisdiction in Pune, but for Zone II. Bawche was the deputy superintendent in Gadchiroli district and conducted the specious investigation from August 2013 onwards, and steered the prosecution in a trial that eventually failed to stand the test of law. It only resulted in the six defenders’ unwarranted incarceration over an average of about eight to nine years.

Another officer named by Pawar before the commission was Bawche’s guide and instructor in the Gadchiroli case: Ravindra Kadam, then a deputy inspector general, who subsequently became joint commissioner at Pune, and retired shortly thereafter. It needs only the joining of dots to realise how the very same officer trio went on to form a core of the cabal that tucked the feather of the Elgar Parishad case on the Pune Police’s cap.

A monstrous edifice for a case founded on clay

As detailed in the first part, Pawar was questioned multiple times during his cross-examination about any evidence regarding the involvement of anyone from the BK16, in the evidence of the violence extensively recorded before the commission. In defence, Pawar did not refer to anything on the commission record—which included scores of police reports and chargesheets encapsulating all the possible violence that occurred surrounding the bicentennial Bhima Koregaon commemoration. Instead, he repeatedly cited the Elgar Parishad chargesheets—comprising tens of thousands of pages of documents, not one of which contained even an iota of evidence to link the mob violence at Koregaon Bhima on 1 January 2018 with the Elgar Parishad of 31 December 2017.

Even Pawar’s own chargesheets–the final report of the investigation filed on 15 November 2018 and the first supplementary final report filed on 21 February 2019—as well as the second supplementary final report filed by the NIA on 9 October 2020, offer no cogent connection between the two events. The unusually voluminous material carries just two probable sources of incriminating evidence.

The first is a variety of documents—an incredulous genre of digital fiction, as we shall see in part three of this series—recovered from the electronic devices allegedly seized from the residences of the accused. The second source is the testimonies of half a dozen unknown individuals classified as “protected witnesses,” five of whose statements were also recorded before a judicial magistrate. While their identities remain undisclosed, their testimonies show that the crucial ones happen to be former Maoists who surrendered to the state, ostensibly on terms that would deem them as nothing but stock witnesses.

Even if seen without any discernment, the evidence at face value is at most suggestive of a keen interest in following some of the developments related to contemporary Maoist activities, but lacks any vital connection with any cogent offence. Most crucially, no terrorist act could possibly be alleged as committed, or even plotted in this case. The evidence holds no relevance to any role in the anti-Dalit mob violence at Koregaon Bhima, or for that matter, anything to do with any Dalit retaliation or chaos anywhere in the country either.

Instead, the investigators appear to have taken undue advantage of a lone procedural provision: Section 173 (8). This subsection of the Code of Criminal Procedure forms one of many easily abusable tools within criminal law, by effectively allowing investigating officers to continue their investigation into a case indefinitely, adding on as many layers of allegations as they may please. In UAPA cases, where the investigator cannot be a low-ranking officer, an otherwise competent officer trained to apply the technological skills involved in accessing digital data of suspects could have a lot of incriminating layers to deploy.

The prosecution has also been particularly tardy in complying—unless compelled by a legal challenge—with the procedural mandate of supplying all incriminating documents to the defence before a trial commences, under Section 207 of the Code. The prosecution has claimed a total of 363 witnesses during a high court hearing in January 2025, but the chargesheets only list 48 witnesses with statements actually recorded and annexed.

A genesis that may engender the nemesis

Since receiving copies of the first supplementary chargesheet in February 2019, the defendants and their counsels have been running from pillar to post—between the special NIA court and the Bombay High Court—for the prosecution’s documents arrayed against them. Only after all the documentary evidence, whether explicit or implicit, is provided to the defence team, would the case be able to enter unhindered into the trial stage.

To be sure, the NIA has so far not appeared to be in any great hurry to proceed to trial. The case has also faced a number of challenges from the defendants at the pre-trial stage, with multiple petitions pending at the high court for quashing the case against a few individual defendants, and most likely a few more for a discharge, even as the prosecution may prefer to expedite the framing of charges for a trial.

The case that was registered on 8 January, and became synonymous with the electrifying 31 December 2017 Elgar Parishad event, was curiously belated. Such a delay in filing a first information report could itself be a potential valid ground for a discerning court to reasonably doubt whether the allegations were an after-thought. Malice, as most judges would know, often begets delays in registering FIRs.

Until March 2018, the case carried minor charges, alleging incendiary speeches, recitation and singing, which were purported to have instigated the violence and chaos at Koregaon Bhima. But, as we have seen so far, the case since its genesis, could very well be looking at its nemesis.

The slim silhouette of the Gadchiroli acquittal in Mahesh Kariman Tirki portends an inevitable threat to the monstrous heap of chargesheet documents that the NIA has been entrusted to champion.

Spate of raids-seizures-arrests

On 17 April 2018, the Pune Police conducted the first wave of raids and seizures, without search warrants, which were actually denied twice, even after an in-camera hearing of Pawar’s second application for the same. The raids were conducted at the residences of multiple suspects, in the cities of Mumbai, Pune, Nagpur, and Delhi. The digital contents of the devices allegedly seized from Wilson and Gadling became the ground for the invocation of the UAPA in May that year. A second wave of raids and seizures followed, on 28 August, against at least six others in Hyderabad, Ranchi, Faridabad, Goa, Thane and once again Mumbai.

Both raid-and-seizure waves crested with concerted arrests. The first set took place on 6 June, of four persons first raided in April, and one more whose house was purportedly subjected to raid-and-seizures on the same day as her sudden arrest, though her arrest memo does not mention any seizure. They became the BK5:

1. Sudhir Dhawale;

2. Rona Wilson

3. Surendra Gadling

4. Shoma Sen

5. Mahesh Raut

Each of them well-known human-rights defenders who may have crossed paths over some cause or the other, such as Wilson and Gadling had over the state’s persecution of Saibaba. Naturally, then, there would be calls exchanged between two or more of them, which could be brought in as evidence of a fabricated conspiracy, without the voice recordings to alleviate the inevitable doubts. The court empowered with taking cognisance would not have bothered to see if the alleged call records carried any conversation records to help determine if there was really any incriminating evidence. The Pune Police cabal must have been unduly confident on account of just such a reading of the call records in the Gadchiroli case until the very end of trial.

The second set of arrests occurred simultaneously with raids and seizures on 28 August. Under the higher judiciary’s orders, the six HRDs were detained for months at their own houses, only to be thrown behind bars later—two of them on 26 October, another the next day on 27th, and the fourth on 17 November. That raised the number to nine. More raids and seizures followed in September 2019, followed by more arrests in July and October 2020, which made them the BK12:

6. Varavara Rao

7. Arun Ferreira

8. Vernon Gonsalves

9. Sudha Bharadwaj

10. Gautam Navlakha

11. Anand Teltumbde

12. Hany Babu.

The 2020 operations gathered new steam after the NIA took over the reins from the Pune Urban Police, which was red-flagged in the wake of a political regime change in Maharashtra in 2019. In September 2020, a fourth wave of arrests took place, this time targeting the core members of Kabir Kala Manch: Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor, and Jyoti Jagtap. The three members of the cultural collective were arrested on 7 and 8 September—all three of their homes had been raided and “evidence” from them seized, back in April 2018. At the time of publishing, all three remain in custody.

The last, but certainly not least, invidious infringement of fundamental freedoms took place a month later. Stan Swamy’s electronic devices had already been seized in two raids, on 12 June and 28 August 2019, by the Pune Police. The author of scores of insightful articles, including in support of the Pathalgadi movement for the self-determination of the Adivasis of Jharkhand, Swamy was an endearing father-figure to a large community of social and political activists. He was arrested on 8 October 2021. Less than a year later, he left behind a huge repository of memories for a truly democratic Indian society and polity, breathing his last in custody, in a private missionary hospital, where he was admitted too late. He was denied the requisite medical treatment for a critical diagnosis of Parkinson’s, which only an expedited release on bail could have ensured.

His arrest completed the construction of the BK16:

13. Sagar Gorkhe

14. Ramesh Gaichor

15. Jyoti Jagtap

16. Stan Swamy

Examining the “probative value of the evidence”

In December 2019, around the time when Sharad Pawar, the doyen of Maharashtra’s secular establishment politics, threw his weight behind the Elgar Parishad accused, The Caravan came out with a shocking forensic analysis of electronic evidence. Malware was detected in it! The report suggested that the seized device was distinctively compromised. As the matter was referred to the USA-based Arsenal Consulting, it triggered a spate of authentic reports of cognisance-worthy probes conducted by internationally renowned cyber forensic labs.

While vicissitudes in many a long-drawn snake-and-mongoose battles in courts continue, the “urban Naxal” conspiracy cases bereft of terrorist acts have lost much of their steam. In July 2023, the Supreme Court passed a crucial bail judgment, ordering the release of the Mumbai writer-activist duo Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira. The singular bail verdict enriched case law in favour of granting bail as many as five years into judicial custody without trial, despite grave charges under the UAPA as well as Indian Penal Code offences related to anti-state conspiracy, waging war and sedition.

The ground on which the court granted relief was an indisputable consideration of the prima facie probative value in the evidence, in a situation where the trial court seems in no position to conclude the trial anytime soon. The propensity of cases woven around the narrative of “urban Naxalism” to not generally constitute any commitment of acts that could fall under the purview of terrorist acts went a long way towards the Gadchiroli acquittals. Since then, either the snake has lost some of its sting or the mongoose its viciousness.

In April and May 2024, Shoma Sen and Gautam Navlakha secured bail at the Supreme Court, with the NIA-led prosecution unable to justify their prolonged incarceration without trial. In fact, the state even acknowledged that there was no need for Sen’s continued incarceration. Soon after, the Bombay High Court even heard arguments on petitions by Sen and Wilson—filed over three years earlier—to quash the case against them in its entirety. But just before the last winter vacation, the court stopped short of formally drawing conclusions.

The petitions, when seen together, present the case in all its dubious shades, and reach many notches above the minimal criterion for relief—the prima facie lack of probative value of the evidence. Whether the quashing petitions would be heard once again in the near future, by a new bench, and whether any verdict would be pronounced anytime soon, may be seen as the pegs of hope on which the future trajectory of the case hangs.

In Gonsalves and Ferreira’s bail judgment, the Supreme Court examined the probative value of the evidence sought to be relied upon by the prosecution. One by one, the court delved into every allegation and each provision under which the duo was charged, and held that the prosecution evidence was insufficient to establish, even prima facie, the guilt of the accused.

It noted that merely the possession of certain kinds of literature and documents did not prima facie amount to any offence as alleged by the prosecution. Further, the court stated that the allegation against Ferreira of handling finances also cannot be linked to any terrorist activity, on the basis of the evidence placed on record by the prosecution. The court also found that none of the letters and documents relied on by the prosecution, in an attempt to establish the duo’s connection with a terrorist organisation, were actually recovered from either’s possession. Ultimately, the Supreme Court held that the evidence of the prosecution had “weak probative value or quality,” with no prima facie case made out against the two, and directed their release.

Are there any immediate possibilities of release for the remaining BK-6?

The rationale of weak probative value or quality of the evidence could very well apply to the favour of the remaining six of the BK16—Raut, Jagtap, Gaichor, Gorkhe, Gadling and Babu. In fact, the Bombay High Court has already found the allegations against Raut too tenuous and granted him bail, though his release remains held up in the corridors of New Delhi. The allegations against Raut were similar to those against Gonsalves and Ferreira, vis-à-vis the handling of finances and the connection with the banned CPI (Maoist), which the police sought to establish through letters and documents not recovered from him. As such, Raut deserved relief at par, especially considering that he has been in prison since the first set of arrests, longer than Gonsalves and Ferriera.

Both Raut and Jagtap seem to have been deemed as having “Maoist links” on the basis of no credible evidence but hearsay. Raut’s charge relies on an activist-advocate in Mumbai who allegedly cited a newspaper report to claim that he may have recruited cadres for the Maoists. Against Jagtap, the prosecution has claimed that the Kabir Kala Manch is a frontal organisation for the Maoists, and a protected witness has purportedly stated that she had visited a training camp within eastern Maharashtra back in 2011. Clearly, there is no corroboration in the available evidence to substantiate these claims of the prosecution against Raut and Jagtap. Moreover, none of these allegations have any connection to anybody’s alleged role in the Elgar Parishad, or to anybody having possibly instigated the violence in Koregaon-Bhima.

The allegations against Jagtap are exactly identical to those against Gorkhe and Gaichor. What was most striking with regard to the three KKM activists is that the allegations in question do not constitute any offence specific to the Elgar Parishad case. Both allegations, that about the KKM being a frontal organisation—without any specific government notification or proven case thereof—and about the Maoist training camp, are actually part of an older case, from over a decade ago, registered by the state Anti-Terrorism Squad. All three were arrested in that case and released on bail despite those unsubstantiated claims. The same allegations, not even weighed in their previous trial as yet, are once again cited at the Supreme Court to deny Jagtap even the opportunity of an early bail hearing in her second case.

By the yardsticks set in the previous Elgar Parishad bail judgments of 2023 and 2024, equality before the law would mandate that all the four youngsters be released before long. But experiences at the Supreme Court have been far too varied in recent years for us to hope for consistent jurisprudence when it comes to the alleged younger supporters of the Maoist revolutionary movement. It may not be incorrect to suppose that the highest rung of the judiciary may be disinclined to look upon activists and researchers on the wrong side of law with the same empathy as with the old and the comfortably housed.

The two others still in prison are defendants accused of possessing incriminating documents allegedly recovered from their own electronic devices, just like the recently released Wilson: the advocate, Gadling, and the professor, Babu. But does the prosecution’s purported evidence against them establish the allegations? The astonishing acquiescence on the part of the state with respect to Wilson and Dhawale’s bail reflected the state’s assessment that a prima-facie reading of the available evidence, ahead of the trial, would establish its low probative value and poor quality.

In Babu’s case, it may suffice to cite accounts of the NIA’s interrogation prior to his arrest, as described by him to his family members. Babu was asked to explain how the incriminating files found in his laptop hard disk were neither indicated as created nor accessed by him, ever before the seizure of the laptop. What could he have answered? He had never seen those files, had no knowledge of them, and the NIA also seemed to believe so. The central agency had, after all, taken over the case at a very late stage, and might not have comprehended how the Pune Police proceeded despite such poor quality of incrimination. Yet, under Devendra Fadnavis as chief minister and home minister, the Maharashtra government allowed these police officials to carry out the arrests of those before Babu, based on weak evidence of suspicious origins. So, the NIA seemed to have blindly followed suit, arresting Babu too.

In fact, the NIA’s fear of a thorough prima facie probative evaluation of the evidence, when it refrained from opposing Wilson’s bail at the Bombay High Court, was not misplaced. “The credibility of the electronic evidence relied on by the prosecution has always been highly doubtful,” said a lawyer closely associated with the defence team. At no event could the electronic evidence sufficiently prove the guilt of the accused “beyond reasonable doubt,” the lawyer added.

First of all, at the time of seizure of the electronic devices, the investigation agency failed to generate hash values. The value changes with any change in the content of the file. The only set of hash values recorded in the charge-sheets are MD5 values. These have been recorded after the digital contents of the various seized devices were “acquired” on sterile hard disks at the respective state forensic science laboratories in Pune and Mumbai.

“Generating the hash value at the time of the seizure could ensure that the electronic device would not be tampered with after its seizure.” the lawyer opined. We found from our perusal of the case documents that no such process was undertaken by the investigating agency to “secure” the seized electronic devices, as required by the law governing the sanctity of digital evidence. The lawyer confirmed that thereby the credibility of all the electronic evidence in the Elgar Parishad case was seriously compromised. The lawyer added: “This fact becomes all the more disparaging for the prosecution in light of several reports published by esteemed international laboratories which have independently examined the electronic devices of the accused and come to the conclusion that the same electronic devices have been subjected to malware, since much prior to their seizure, unbeknownst to the accused themselves.”

These independent cyber forensic examinations, conducted at more than one credible international laboratory, have clearly indicated the hacking of various electronic devices seized from three of the defendants—Surendra Gadling, Rona Wilson, and Stan Swamy—in the case. These also indicated there were documents digitally delivered by a hacker into their devices. The earliest of these reports are very much part of the pending quashing petitions of Wilson, Sen and Swamy, with more such examinations, if not quashing petitions, still in the pipeline. Babu’s defence team chose not to comment on the matter.

As the only source of the alleged incriminating evidence to support the allegations, the electronic evidence simply cannot be considered secure electronic records. The digital part of the incriminating evidence would, therefore, potentially not be admissible in the evidence at all. That would deprive any incriminating witness statements of the essential aspect of corroboration. Hence, the probative value of the evidence envisaged in the huge volume of documents forming the Pune Police and NIA chargesheets virtually dwindles down to naught.

Given the overwhelming analysis revealing the implanting of fabricated documents in the seized electronic devices, one of the quashing petitions has, as a corrective measure, also sought the constitution of an independent Special Investigating Team. In fact, the previous state government in Maharashtra, led by the Maha Vikas Aghadi alliance forged by the veteran politician Sharad Pawar, had even announced that an SIT would investigate the alleged fake case against the BK16. The move was scuttled, in January 2020, when the union home ministry handed over the investigation to the NIA, making no bones about pre-empting any such remedial measure.

Following the elections in November 2024, the BJP returned to power with Devendra Fadnavis as chief minister, under whose previous tenure, the Koregaon Bhima violence and Elgar Parishad event cases as well as the commission proceedings took their current shape. While Sharad Pawar and his allies have been forced into the opposition benches, India’s independent judiciary would now be put to test on whether the ongoing travesty could be brought to an early end with the required truth-seeking exercise.

This is the second report in a three-part investigative series on the Elgar Parishad/Bhima Koregaon case. Read part one here and part three here.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.