BK-16 Prison Diaries: Varavara Rao on prisons as institutions of corruption, sadism and dehumanisation

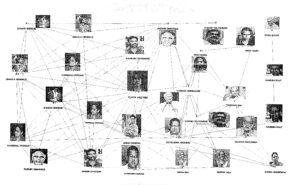

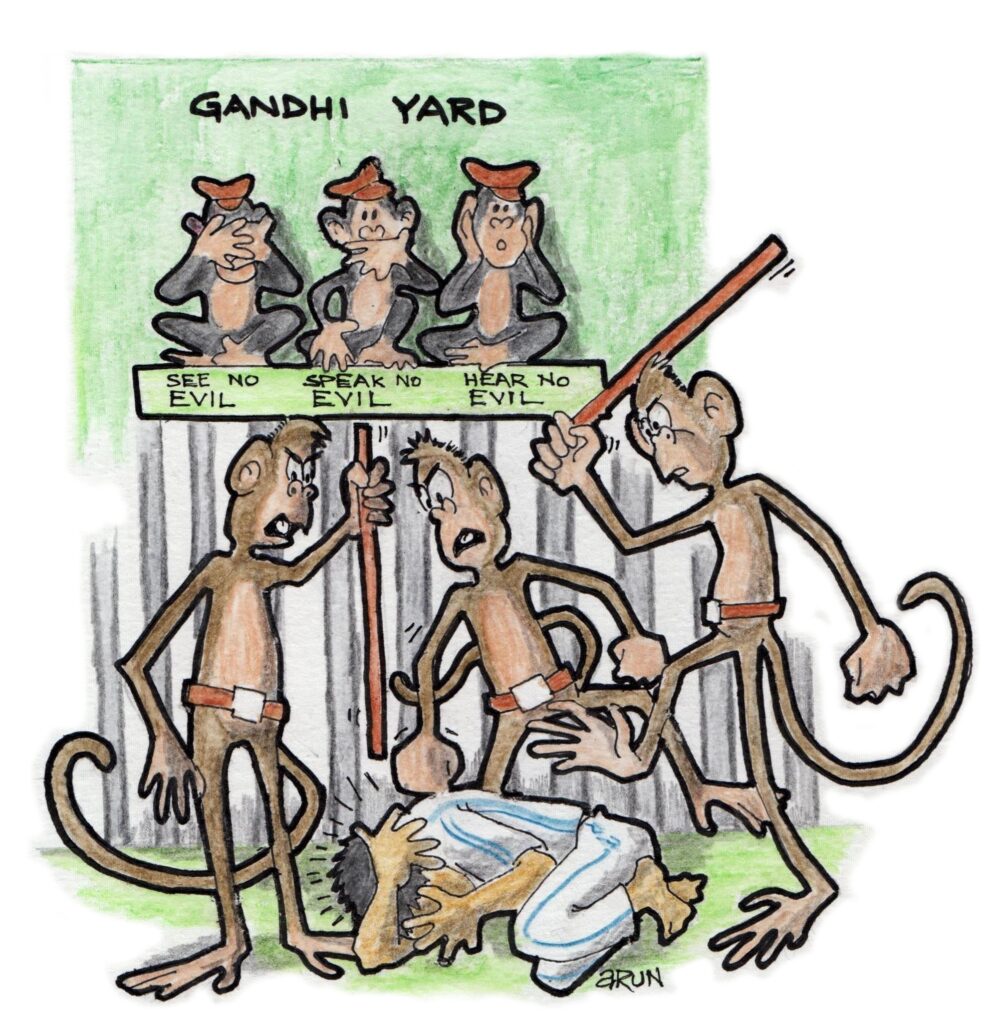

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork.

The term “correctional institutions,” as prisons are sometimes known, is actually a misnomer. It would be more appropriate to term them institutions of sadism, dehumanisation and corruption, given that the whole system is rooted in these practices. The state does not in fact want the prisons to be correctional institutions like those shown in the Hindi films Do Ankhen Barah Haath or Bandini.

The jail officials, however, understand the prisons as actually envisioned by the state, and they act accordingly. Though they are given uniforms like the police outside, they don’t enjoy the same power. Yet, they always compare themselves with their police equivalents in nomenclature, referring to those higher in the hierarchy as superintendents and deputy superintendents, and those in the lower ranks as sipahis, like the police constables. But while the police are given such enormous powers to deal with people—rich and poor, senior or not—the prison staff do not have the same powers. That inferiority leads them to see the inmates as criminals, and given their uniforms, it is all the more humiliating. So they become perverse, cynical and sadist—as the state expects them to.

Institution of sadism

There is a sadism in officials of the prisons at all levels, including the prison guards and even the warders. I will give an example from my experience in Yerawada Central Jail, where I was kept during 2018-2020. My fellow political prisoner Vernon Gonsalves and I were put in the high-security ward known as Phansi Yard, where the people facing capital punishment were kept. It has 20 cells, and we were in numbers 18 and 19. My neighbour was a 23-year-old Muslim convict, one of the infamous accused of the Shakti Mills gang rape case. He was headstrong, or you may say, self-confident. This is not at all expected or tolerated by the jail officials.

It is a known but unacknowledged practice in jails to burn newspapers—or anything else that catches fire—in order to make tea or recook the so-called food that is served. Generally, this is also allowed by the officers, as long as it is not done in defiance of the prison staff, in their presence. One evening, my neighbour was preparing tea when the jailor-in-charge, who had gotten a tip, ferociously came to his cell and kicked him on his back, throwing him upside down onto the ground. The jailor ruthlessly beat him with a lathi and kicked him mercilessly, abusing him with all sorts of foul words throughout the assault.

We could not bear it. Vernon and I tried to stop the jailor, and though he ordered us into our cells, he finally stopped and left.

The real cause was not the preparation of tea. The jailor had just been waiting for an opportunity. My neighbour had broken another known but unwritten rule of prison, and the brutal assault was a vengeful punishment for this earlier act of defiance.

Usually, if we wanted to make a request during the weekly superintendent rounds, we were supposed to inform the concerned jailor. First, he would inform the senior jailor, who informs the superintendent before the round itself. It is only then that the superintendent stops in front of your cell to ask your request. This procedure is scrupulously followed if the concerned jailor thinks that your request is genuine.

One day, there was a surprise visit by the Additional Director General of Police and Inspector General of Prisons, who is an officer of the Indian Police Service cadre. My neighbour, the Muslim convict, asked why mutton or chicken could not be allowed to be purchased from the canteen once a month, instead of the then system of six times a year, for two festivals of each of three religions. To the IPS mind, the question seemed reasonable. But after his visit, this defiance became a major talking point. The prison administration as a whole wanted to teach a lesson to this headstrong Muslim youth.

The sadism of the prison officials was so entrenched into the prison system that they even had a designated spot for it. There is a block in Yerawada called Shanti Van, where Gandhi was kept, and where the Poona Pact was signed between him and BR Ambedkar. It is kept as a place to show to VIP visitors to the prison. It is full of very big trees, many of which are Ashoka trees, and also holds the jailors’ office. Shanti Van was on our left side. On our right was the place for the gallows, and beside it stood the bakery.

We were never allowed into this Shanti Van. As time passed, whenever we heard sounds of beating or the cries of “hardcore” inmates, we learnt that Shanti Van is the isolated, secure block of the prison used to teach a lesson to poor notorious prisoners.

Institution of dehumanisation

Jail is a dehumanising institution, both for the administrators, as well as the administered. It starts with jhadthi, or search. When you enter through the inner gate of the prison, you are expected to remove all the clothes on your body, supervised by a jailor. The jhadthi amaldar—the prison guard who does the search—puts his hands in your private parts to search for illegal items. In such an institution, you cannot expect sensitive human feelings. My granddaughter Tara once sent me a paper boat as a bookmark along with her letter. I was taking a book to read while going to a court hearing. The jhadthi amaldar took away the bookmark, unfolded it, and threw it away, casually commenting, “What is there in it except a kora kagaz [a blank paper]?”

In Maharashtra prisons, and also after coming outside due to the bail conditions imposed by the court, I have not been allowed to meet my co-accused. The superintendents in Yerawada and Taloja jails allowed Vernon to stay in the next cell, or with me in barracks, or even in hospital wards in Taloja all along, which alone has saved my life, besides the timely treatment in Nanavati hospital. But that first-hand experience has to be told by Vernon, and to some extent is also known by Arun Ferreira, Anand Teltumbde and the late Fr Stan Swamy, who were in the hospital ward at times, as well as my wife, daughters and my nephew, Venu. All through my serious ailment I was in hallucination, writing with fingers all the time on floor and walls while lying down, living in an entirely subconscious world. It was a test for the service of my comrades concerned and a period of agony and anxiety for my wife Ms Hemalatha, my daughters and Venu; while for me, it was a bliss in ignorance.

Throughout this period, my experience was that of a dehumanised jail system. We were shifted to Taloja jail and allotted different barracks on 1 March 2020. At the entry point itself, Surendra Gadling and Vernon asked the superintendent to keep all of us together, where we could place our chargesheet and related documents in one place to be studied by the lawyers among us, as well as those of us who are well versed with the law, particularly the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and the National Investigation Agency Act.

The superintendent took it to mean that we were asking him to keep us in the high-security Anda cell. “No, no, how can I keep you in Anda cell? You are political prisoners and Anda cell is a place to keep gangsters.” So he divided us into five different Circles along with other undertrial prisoners, keeping not more than two of us together in one Circle. Vernon and I were put together in a barrack with 30 people, more than its capacity.

This change from a single cell to a crowded barrack caused me breathlessness immediately after the evening lock-up. The jail doctor had to be called. Both of us were given a small portion of the little available space in one corner to lay out our sleeping rugs. There was no space to even stretch our arms and legs. In one corner of the barrack—of every barrack, in fact—a space has to be created for an idol of Ganesh and other deities for daily evening prayers.

On the other side stood four toilets, with the space in front of them designated for keeping water in drums and washing ourselves. It was very unhygienic to go use the toilet and to take a bath. The bathing area was also very slippery. On top of that, I was already a patient of chronic constipation, I had twice been operated for piles, in 1983 and 1993, and I had also undergone an operation for prostate enlargement in 1999. Moreover, the food given in the jail was also prepared in unhygienic conditions. On the day of Ramzan in 2020, I suffered from loose motion and vomiting. I vomited several times and was sent to the JJ hospital, but by the time I reached there, there was no specialist available.

Describing all these difficulties and my health condition, I wrote an application to the superintendent, and submitted it to the jailor-in-charge, seeking to be produced before the superintendent after his round. The colonial practice requires a senior jailor to deem the application worthy, following which after the round, the applicants have to stand in a line—without chappals or shoes—at the entrance of the Circle to be produced before the superintendent. The number of such applicants should be as minimum as possible. So we were not more than eight.

The superintendent asked me, “Kabhi gir gaye kya?”—Have you ever slipped and fallen? I said, “No.”

“Jab gir gaye toh dekhenge”—When you fall, then I will consider.

The whole official team laughed at his wit and the senior jailor added, “Wahan gir gaye tho koi uthane ke liye bhi nahi hoga! Yahan vo madad ke liye itne log hai.” (If he falls there, there will not be anyone to lift him. Here there are so many people to come to his aid.)

The superintendent and senior jailor were reading my application as a request for us to be shifted to the Anda cell, as if it were an island or paradise in the deserted Taloja jail.

Institution of corruption

The real issue is, as the superintendent stated, that the Anda cell is meant for gangsters, the very rich and politically influential people to be kept in isolation, so that the corrupt practices mutually entered into will not be known to others, particularly the political prisoners. But ironically, after COVID-19, about seven or eight of my co-accused, including Ramesh Gaichor, Sagar Gorkhe and the advocate Surendra Gadling were shifted to Anda cell. The corruption of Taloja jail officials, in connivance with the rich and politically or socially influential people, has now come to light. Surendra, Sagar and Ramesh, supported by the other BK07/BK16 in Taloja jail, have exposed these practices.

Interestingly, for the first time in the history of political prisoners all over the country, we now see indefinite hunger strikes against corruption, unworthy food being supplied, solitary confinement and 24-hour lock-ups, transfers to distant prisons, not being allowed to sit for exams etc. It has spread from Taloja to the central prisons of Hyderabad (Chanchalguda), Kerala, and Bihar.

In this aspect of corruption too, my observations during my 51 years of intermittent jail life from 1973 onwards, has shown that there is added sadism. Since the jail officials curse themselves for the unequal payment to their police counterparts, the sadist solution has been to eat away the meagre allowance given for the inmates’ battha—food, cutting one-third of it, and also substantially cutting the wages for convicts and lifers. They do not speak of the privilege and luxury of the superintendent and jailors who use the bonded labour of convicts to keep the bungalows and garden in their official quarters clean as a mirror. In several prisons, at least 16 convicts work at the superintendent’s bungalows as bonded labour.

Caste and communal discrimination

In this manual labour comes the caste discrimination. Even in the factories of jails, the trades given to the lifers and convicts are strictly based on caste hierarchy. Even among the undertrials, only the Dalits are given the work of toilet cleaning. The system therefore ensures that the flow of Dalits into the prisons continues uninterrupted, as their absence would hinder the cleaning of toilets. Over the last 51 years, I observed that the communities that are in a huge majority in jails are Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and backward castes. In Yerawada jail, we were living with around 35 death penalty convicts, all of them either Muslims, Dalits or from poor backward castes.

Among the four Muslims, two were political prisoners, Asif and Faisal, implicated in the Bombay train blasts case. Asif is a civil engineer from Jalgaon, branded as a Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) organiser, and Faisal from Mumbai, branded as a Lashkar-e-Taiba member. Both helped me understand the meaning of Urdu, Arabic and Persian words and the religious connotations, images, contexts for translating Gulzar’s Suspected Poems and Nazrul Islam’s poetry, from the original Urdu/Hindustani in Devnagari script for Gulzar, and from English for Nazrul.

Among them, I can say with close observation Asif is religious but not communal, and he thoroughly supports election politics, while of course being opposed to Sangh Parivar politics. Faisal is a fundamentalist, but dead against terrorist attacks in public spaces. He must have gone to Saudi Arabia for business purposes. As noted by Abdul Wahid Sheikh, one of their co-accused who was later acquitted, in his book Begunah Qaidi, I too firmly believe that they are both innocent in this particular criminal conspiracy case. They told me that even the central intelligence agencies have acknowledged the same.

Asif and Nitin, a Dalit undergraduate from a college in Pune, were my regular co-walkers in the open area in front of the prison cells. Nitin is an Ambedkarite, a good singer and articulate. A team from National Law University Delhi has taken his case to fight against his sentence of capital punishment, and I can vouch for him that he is innocent. He happened to be visiting his cousin Santhosh’s home to obtain certificates from the village authorities, which were necessary to sit for his final graduation examination in Pune, on the very day that his cousin was involved in the infamous Kopardi case of rape and murder of a Maratha college student. After my release from prison, I read that the main accused in the case died by suicide in the Yerawada jail.

Custodial deaths

Of late, with the connivance of the central government, custodial deaths of political prisoners in jail has become a policy and practice of the Maharashtra government. The whole world knows about the case of Father Stan Swamy, with whom I lived 40 days in Taloja prison hospital.

While in Yerawada, Kanchan Nanaware from the women’s jail was suffering from a heart ailment, and died from a blood clot in her brain in January 2021, after her medical bail plea was rejected twice. Her husband, Arun Bhelke, was in Anda cell with our comrades and sometimes we would meet in escort vans, as their case was also in our court. My encounters with Kanchan Nanaware were more in the hospital in Pune, where she used to inform me that no specialist is available because they had left by the time we would reach. Upon her death, even her husband was not informed about her hospitalisation until after the jail officials cremated her in the women’s jail itself. Arun Bhelke’s petition about this custodial death is pending in the Bombay High Court, just like that of Father Frazer Mascarenhas’ petition on the custodial death of Father Stan Swamy, in which three judges have recused themselves from hearing the case.

Comrade Narmada, or Uppuganti Krishna Kumari, was arrested with her husband Rani Satyanarayana in Hyderabad in 2019, while she was undergoing treatment for fourth stage cancer. She died in custody, without being provided any treatment.

The worst case is that of Pandu Narote, a robust 37-year-old Adivasi convict along with GN Saibaba, who died with a high fever due to the utter neglect of the Nagpur high-security prison’s authorities. Narote was acquitted twice, by the high court. But even a judicial acquittal was not heeded in his case, and he was left to die in custody.

GN Saibaba’s death also amounts to custodial death in essence, if you understand it in the context of the structural violence inflicted upon him. Though he was released by the Bombay High Court’s acquittal order in March, which the Supreme Court refused to stay, it was his accumulated health deterioration over a ten-year-long prison life that wrung out all his energy. He could live outside only with his will power. He was sent to die, as Gramsci in Italy by the Fascist regime.

Surviving this institution

Political prisoners, particularly the BK-16, have overcome all of these ordeals and turned their jail life into a centre for educating themselves and the inmates, inculcating secular values among the inmates. Vernon used to take classes for the capital punishment convicts who have opted to learn to write and read from 9am to 11am. Slowly the numbers have increased and almost all young inmates joined in learning.

Nitin benefitted very much from this and he was encouraged to write a letter to the NLU Delhi legal team in English. They felt very happy about that and sent him the biography of Abraham Lincoln to read, advising him to continue to write to them in English, not only about his case but whatever he feels and thinks.

Surviving in these institutions also included small, yet significant, acts of resistance. For instance, the practice of addressing the jail officials, particularly during their rounds and visits, would be to say “Jai Shree Ram” and “Salaam Alaikum.” We decided that instead, we should all say “good morning” among ourselves and also to jail officials. Over time, though some convicts addressed the jail officers with “Jai Hind,” in our daily conversations, “good morning” became the standard practice.

This helped the Muslim convicts because the superintendent in his rounds invariably said Jai Hind to every inmate in response. One day, he asked me, “Why are you not saying Jai Hind in response?” I said, “Before you address me, I am raising my hand and saying namaskar.” He repeated, “Why are you not saying Jai Hind?”

“Our constitution is secular,” I said. “Oh I see,” was his embarrassed reply.

Our time was mostly spent with the young, downtrodden people—maybe the wretched of the earth, some of whom are innocent, yet waiting for the gallows—playing volleyball, chess, and carom; spending time singing and chatting; reading newspapers; and walking and talking with us. As a result, our burden of relatively little incarceration was not felt as strongly. We were inspired by their lust for life, even on the threshold of the gallows. There is, of course, a dark side to it. Particularly at night, even psychiatrists prescribe them sleeping pills, and most of them are addicted to them. Till they get sleep, some of those who can read get erotic books. Of course, Gandhi and Savarkar’s complete works are available in the jail library in three languages—Marathi, Hindi and English.

On my part, I spent most of the lock-up time during the daytime writing and translating Gulzar and Nazrul, while the nights were for reading. That way, Yerawada was more fruitful for me.

Persecution perpetuated

Even during my arrest, the persecution and harassment continued. New production warrants (for the 2005 case in Karnataka and the 2016 case in Ahiri Gadchiroli, along with Gadling) were issued while I was in Yerawada jail. When the NIA took over the Elgar case, it struck my family like a thunderbolt. I was moved to Taloja, due to which I got COVID. My home as well as those of my two daughters, Anala and Pavana, were raided most ferociously, as was that of my friend, who is a journalist and a writer. My sons-in-law, KV Kurmanath and K Satyanarayana, are shown as witnesses and summoned for interrogation to the NIA Mumbai office during the time when I was almost on my deathbed.

The move to Taloja also meant moving from Pune to Mumbai for my family. For my wife, the language and the place were alien. As she and my family were getting adjusted to Pune for window mulaakats—jail visits—and court hearings, traveling in the morning to Pune and then leaving for Hyderabad, the shift to Mumbai disturbed the whole routine. Of course, the dark cloud of COVID-19 resolved the mulaakats issue, but it was the longest period of no communication.

More than anything, the conditions of medical bail for me made us more immobile, not only for me but for my wife too. It is now bail for me and jail for her.

Related Posts

BK-16 Prison Diaries: Varavara Rao on prisons as institutions of corruption, sadism and dehumanisation

The term “correctional institutions,” as prisons are sometimes known, is actually a misnomer. It would be more appropriate to term them institutions of sadism, dehumanisation and corruption, given that the whole system is rooted in these practices. The state does not in fact want the prisons to be correctional institutions like those shown in the Hindi films Do Ankhen Barah Haath or Bandini.

The jail officials, however, understand the prisons as actually envisioned by the state, and they act accordingly. Though they are given uniforms like the police outside, they don’t enjoy the same power. Yet, they always compare themselves with their police equivalents in nomenclature, referring to those higher in the hierarchy as superintendents and deputy superintendents, and those in the lower ranks as sipahis, like the police constables. But while the police are given such enormous powers to deal with people—rich and poor, senior or not—the prison staff do not have the same powers. That inferiority leads them to see the inmates as criminals, and given their uniforms, it is all the more humiliating. So they become perverse, cynical and sadist—as the state expects them to.

Institution of sadism

There is a sadism in officials of the prisons at all levels, including the prison guards and even the warders. I will give an example from my experience in Yerawada Central Jail, where I was kept during 2018-2020. My fellow political prisoner Vernon Gonsalves and I were put in the high-security ward known as Phansi Yard, where the people facing capital punishment were kept. It has 20 cells, and we were in numbers 18 and 19. My neighbour was a 23-year-old Muslim convict, one of the infamous accused of the Shakti Mills gang rape case. He was headstrong, or you may say, self-confident. This is not at all expected or tolerated by the jail officials.

It is a known but unacknowledged practice in jails to burn newspapers—or anything else that catches fire—in order to make tea or recook the so-called food that is served. Generally, this is also allowed by the officers, as long as it is not done in defiance of the prison staff, in their presence. One evening, my neighbour was preparing tea when the jailor-in-charge, who had gotten a tip, ferociously came to his cell and kicked him on his back, throwing him upside down onto the ground. The jailor ruthlessly beat him with a lathi and kicked him mercilessly, abusing him with all sorts of foul words throughout the assault.

We could not bear it. Vernon and I tried to stop the jailor, and though he ordered us into our cells, he finally stopped and left.

The real cause was not the preparation of tea. The jailor had just been waiting for an opportunity. My neighbour had broken another known but unwritten rule of prison, and the brutal assault was a vengeful punishment for this earlier act of defiance.

Usually, if we wanted to make a request during the weekly superintendent rounds, we were supposed to inform the concerned jailor. First, he would inform the senior jailor, who informs the superintendent before the round itself. It is only then that the superintendent stops in front of your cell to ask your request. This procedure is scrupulously followed if the concerned jailor thinks that your request is genuine.

One day, there was a surprise visit by the Additional Director General of Police and Inspector General of Prisons, who is an officer of the Indian Police Service cadre. My neighbour, the Muslim convict, asked why mutton or chicken could not be allowed to be purchased from the canteen once a month, instead of the then system of six times a year, for two festivals of each of three religions. To the IPS mind, the question seemed reasonable. But after his visit, this defiance became a major talking point. The prison administration as a whole wanted to teach a lesson to this headstrong Muslim youth.

The sadism of the prison officials was so entrenched into the prison system that they even had a designated spot for it. There is a block in Yerawada called Shanti Van, where Gandhi was kept, and where the Poona Pact was signed between him and BR Ambedkar. It is kept as a place to show to VIP visitors to the prison. It is full of very big trees, many of which are Ashoka trees, and also holds the jailors’ office. Shanti Van was on our left side. On our right was the place for the gallows, and beside it stood the bakery.

We were never allowed into this Shanti Van. As time passed, whenever we heard sounds of beating or the cries of “hardcore” inmates, we learnt that Shanti Van is the isolated, secure block of the prison used to teach a lesson to poor notorious prisoners.

Institution of dehumanisation

Jail is a dehumanising institution, both for the administrators, as well as the administered. It starts with jhadthi, or search. When you enter through the inner gate of the prison, you are expected to remove all the clothes on your body, supervised by a jailor. The jhadthi amaldar—the prison guard who does the search—puts his hands in your private parts to search for illegal items. In such an institution, you cannot expect sensitive human feelings. My granddaughter Tara once sent me a paper boat as a bookmark along with her letter. I was taking a book to read while going to a court hearing. The jhadthi amaldar took away the bookmark, unfolded it, and threw it away, casually commenting, “What is there in it except a kora kagaz [a blank paper]?”

In Maharashtra prisons, and also after coming outside due to the bail conditions imposed by the court, I have not been allowed to meet my co-accused. The superintendents in Yerawada and Taloja jails allowed Vernon to stay in the next cell, or with me in barracks, or even in hospital wards in Taloja all along, which alone has saved my life, besides the timely treatment in Nanavati hospital. But that first-hand experience has to be told by Vernon, and to some extent is also known by Arun Ferreira, Anand Teltumbde and the late Fr Stan Swamy, who were in the hospital ward at times, as well as my wife, daughters and my nephew, Venu. All through my serious ailment I was in hallucination, writing with fingers all the time on floor and walls while lying down, living in an entirely subconscious world. It was a test for the service of my comrades concerned and a period of agony and anxiety for my wife Ms Hemalatha, my daughters and Venu; while for me, it was a bliss in ignorance.

Throughout this period, my experience was that of a dehumanised jail system. We were shifted to Taloja jail and allotted different barracks on 1 March 2020. At the entry point itself, Surendra Gadling and Vernon asked the superintendent to keep all of us together, where we could place our chargesheet and related documents in one place to be studied by the lawyers among us, as well as those of us who are well versed with the law, particularly the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act and the National Investigation Agency Act.

The superintendent took it to mean that we were asking him to keep us in the high-security Anda cell. “No, no, how can I keep you in Anda cell? You are political prisoners and Anda cell is a place to keep gangsters.” So he divided us into five different Circles along with other undertrial prisoners, keeping not more than two of us together in one Circle. Vernon and I were put together in a barrack with 30 people, more than its capacity.

This change from a single cell to a crowded barrack caused me breathlessness immediately after the evening lock-up. The jail doctor had to be called. Both of us were given a small portion of the little available space in one corner to lay out our sleeping rugs. There was no space to even stretch our arms and legs. In one corner of the barrack—of every barrack, in fact—a space has to be created for an idol of Ganesh and other deities for daily evening prayers.

On the other side stood four toilets, with the space in front of them designated for keeping water in drums and washing ourselves. It was very unhygienic to go use the toilet and to take a bath. The bathing area was also very slippery. On top of that, I was already a patient of chronic constipation, I had twice been operated for piles, in 1983 and 1993, and I had also undergone an operation for prostate enlargement in 1999. Moreover, the food given in the jail was also prepared in unhygienic conditions. On the day of Ramzan in 2020, I suffered from loose motion and vomiting. I vomited several times and was sent to the JJ hospital, but by the time I reached there, there was no specialist available.

Describing all these difficulties and my health condition, I wrote an application to the superintendent, and submitted it to the jailor-in-charge, seeking to be produced before the superintendent after his round. The colonial practice requires a senior jailor to deem the application worthy, following which after the round, the applicants have to stand in a line—without chappals or shoes—at the entrance of the Circle to be produced before the superintendent. The number of such applicants should be as minimum as possible. So we were not more than eight.

The superintendent asked me, “Kabhi gir gaye kya?”—Have you ever slipped and fallen? I said, “No.”

“Jab gir gaye toh dekhenge”—When you fall, then I will consider.

The whole official team laughed at his wit and the senior jailor added, “Wahan gir gaye tho koi uthane ke liye bhi nahi hoga! Yahan vo madad ke liye itne log hai.” (If he falls there, there will not be anyone to lift him. Here there are so many people to come to his aid.)

The superintendent and senior jailor were reading my application as a request for us to be shifted to the Anda cell, as if it were an island or paradise in the deserted Taloja jail.

Institution of corruption

The real issue is, as the superintendent stated, that the Anda cell is meant for gangsters, the very rich and politically influential people to be kept in isolation, so that the corrupt practices mutually entered into will not be known to others, particularly the political prisoners. But ironically, after COVID-19, about seven or eight of my co-accused, including Ramesh Gaichor, Sagar Gorkhe and the advocate Surendra Gadling were shifted to Anda cell. The corruption of Taloja jail officials, in connivance with the rich and politically or socially influential people, has now come to light. Surendra, Sagar and Ramesh, supported by the other BK07/BK16 in Taloja jail, have exposed these practices.

Interestingly, for the first time in the history of political prisoners all over the country, we now see indefinite hunger strikes against corruption, unworthy food being supplied, solitary confinement and 24-hour lock-ups, transfers to distant prisons, not being allowed to sit for exams etc. It has spread from Taloja to the central prisons of Hyderabad (Chanchalguda), Kerala, and Bihar.

In this aspect of corruption too, my observations during my 51 years of intermittent jail life from 1973 onwards, has shown that there is added sadism. Since the jail officials curse themselves for the unequal payment to their police counterparts, the sadist solution has been to eat away the meagre allowance given for the inmates’ battha—food, cutting one-third of it, and also substantially cutting the wages for convicts and lifers. They do not speak of the privilege and luxury of the superintendent and jailors who use the bonded labour of convicts to keep the bungalows and garden in their official quarters clean as a mirror. In several prisons, at least 16 convicts work at the superintendent’s bungalows as bonded labour.

Caste and communal discrimination

In this manual labour comes the caste discrimination. Even in the factories of jails, the trades given to the lifers and convicts are strictly based on caste hierarchy. Even among the undertrials, only the Dalits are given the work of toilet cleaning. The system therefore ensures that the flow of Dalits into the prisons continues uninterrupted, as their absence would hinder the cleaning of toilets. Over the last 51 years, I observed that the communities that are in a huge majority in jails are Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims and backward castes. In Yerawada jail, we were living with around 35 death penalty convicts, all of them either Muslims, Dalits or from poor backward castes.

Among the four Muslims, two were political prisoners, Asif and Faisal, implicated in the Bombay train blasts case. Asif is a civil engineer from Jalgaon, branded as a Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) organiser, and Faisal from Mumbai, branded as a Lashkar-e-Taiba member. Both helped me understand the meaning of Urdu, Arabic and Persian words and the religious connotations, images, contexts for translating Gulzar’s Suspected Poems and Nazrul Islam’s poetry, from the original Urdu/Hindustani in Devnagari script for Gulzar, and from English for Nazrul.

Among them, I can say with close observation Asif is religious but not communal, and he thoroughly supports election politics, while of course being opposed to Sangh Parivar politics. Faisal is a fundamentalist, but dead against terrorist attacks in public spaces. He must have gone to Saudi Arabia for business purposes. As noted by Abdul Wahid Sheikh, one of their co-accused who was later acquitted, in his book Begunah Qaidi, I too firmly believe that they are both innocent in this particular criminal conspiracy case. They told me that even the central intelligence agencies have acknowledged the same.

Asif and Nitin, a Dalit undergraduate from a college in Pune, were my regular co-walkers in the open area in front of the prison cells. Nitin is an Ambedkarite, a good singer and articulate. A team from National Law University Delhi has taken his case to fight against his sentence of capital punishment, and I can vouch for him that he is innocent. He happened to be visiting his cousin Santhosh’s home to obtain certificates from the village authorities, which were necessary to sit for his final graduation examination in Pune, on the very day that his cousin was involved in the infamous Kopardi case of rape and murder of a Maratha college student. After my release from prison, I read that the main accused in the case died by suicide in the Yerawada jail.

Custodial deaths

Of late, with the connivance of the central government, custodial deaths of political prisoners in jail has become a policy and practice of the Maharashtra government. The whole world knows about the case of Father Stan Swamy, with whom I lived 40 days in Taloja prison hospital.

While in Yerawada, Kanchan Nanaware from the women’s jail was suffering from a heart ailment, and died from a blood clot in her brain in January 2021, after her medical bail plea was rejected twice. Her husband, Arun Bhelke, was in Anda cell with our comrades and sometimes we would meet in escort vans, as their case was also in our court. My encounters with Kanchan Nanaware were more in the hospital in Pune, where she used to inform me that no specialist is available because they had left by the time we would reach. Upon her death, even her husband was not informed about her hospitalisation until after the jail officials cremated her in the women’s jail itself. Arun Bhelke’s petition about this custodial death is pending in the Bombay High Court, just like that of Father Frazer Mascarenhas’ petition on the custodial death of Father Stan Swamy, in which three judges have recused themselves from hearing the case.

Comrade Narmada, or Uppuganti Krishna Kumari, was arrested with her husband Rani Satyanarayana in Hyderabad in 2019, while she was undergoing treatment for fourth stage cancer. She died in custody, without being provided any treatment.

The worst case is that of Pandu Narote, a robust 37-year-old Adivasi convict along with GN Saibaba, who died with a high fever due to the utter neglect of the Nagpur high-security prison’s authorities. Narote was acquitted twice, by the high court. But even a judicial acquittal was not heeded in his case, and he was left to die in custody.

GN Saibaba’s death also amounts to custodial death in essence, if you understand it in the context of the structural violence inflicted upon him. Though he was released by the Bombay High Court’s acquittal order in March, which the Supreme Court refused to stay, it was his accumulated health deterioration over a ten-year-long prison life that wrung out all his energy. He could live outside only with his will power. He was sent to die, as Gramsci in Italy by the Fascist regime.

Surviving this institution

Political prisoners, particularly the BK-16, have overcome all of these ordeals and turned their jail life into a centre for educating themselves and the inmates, inculcating secular values among the inmates. Vernon used to take classes for the capital punishment convicts who have opted to learn to write and read from 9am to 11am. Slowly the numbers have increased and almost all young inmates joined in learning.

Nitin benefitted very much from this and he was encouraged to write a letter to the NLU Delhi legal team in English. They felt very happy about that and sent him the biography of Abraham Lincoln to read, advising him to continue to write to them in English, not only about his case but whatever he feels and thinks.

Surviving in these institutions also included small, yet significant, acts of resistance. For instance, the practice of addressing the jail officials, particularly during their rounds and visits, would be to say “Jai Shree Ram” and “Salaam Alaikum.” We decided that instead, we should all say “good morning” among ourselves and also to jail officials. Over time, though some convicts addressed the jail officers with “Jai Hind,” in our daily conversations, “good morning” became the standard practice.

This helped the Muslim convicts because the superintendent in his rounds invariably said Jai Hind to every inmate in response. One day, he asked me, “Why are you not saying Jai Hind in response?” I said, “Before you address me, I am raising my hand and saying namaskar.” He repeated, “Why are you not saying Jai Hind?”

“Our constitution is secular,” I said. “Oh I see,” was his embarrassed reply.

Our time was mostly spent with the young, downtrodden people—maybe the wretched of the earth, some of whom are innocent, yet waiting for the gallows—playing volleyball, chess, and carom; spending time singing and chatting; reading newspapers; and walking and talking with us. As a result, our burden of relatively little incarceration was not felt as strongly. We were inspired by their lust for life, even on the threshold of the gallows. There is, of course, a dark side to it. Particularly at night, even psychiatrists prescribe them sleeping pills, and most of them are addicted to them. Till they get sleep, some of those who can read get erotic books. Of course, Gandhi and Savarkar’s complete works are available in the jail library in three languages—Marathi, Hindi and English.

On my part, I spent most of the lock-up time during the daytime writing and translating Gulzar and Nazrul, while the nights were for reading. That way, Yerawada was more fruitful for me.

Persecution perpetuated

Even during my arrest, the persecution and harassment continued. New production warrants (for the 2005 case in Karnataka and the 2016 case in Ahiri Gadchiroli, along with Gadling) were issued while I was in Yerawada jail. When the NIA took over the Elgar case, it struck my family like a thunderbolt. I was moved to Taloja, due to which I got COVID. My home as well as those of my two daughters, Anala and Pavana, were raided most ferociously, as was that of my friend, who is a journalist and a writer. My sons-in-law, KV Kurmanath and K Satyanarayana, are shown as witnesses and summoned for interrogation to the NIA Mumbai office during the time when I was almost on my deathbed.

The move to Taloja also meant moving from Pune to Mumbai for my family. For my wife, the language and the place were alien. As she and my family were getting adjusted to Pune for window mulaakats—jail visits—and court hearings, traveling in the morning to Pune and then leaving for Hyderabad, the shift to Mumbai disturbed the whole routine. Of course, the dark cloud of COVID-19 resolved the mulaakats issue, but it was the longest period of no communication.

More than anything, the conditions of medical bail for me made us more immobile, not only for me but for my wife too. It is now bail for me and jail for her.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.