BK-16 Prison Diaries: Stories of love, murder and child marriage from Shoma Sen’s years in prisons

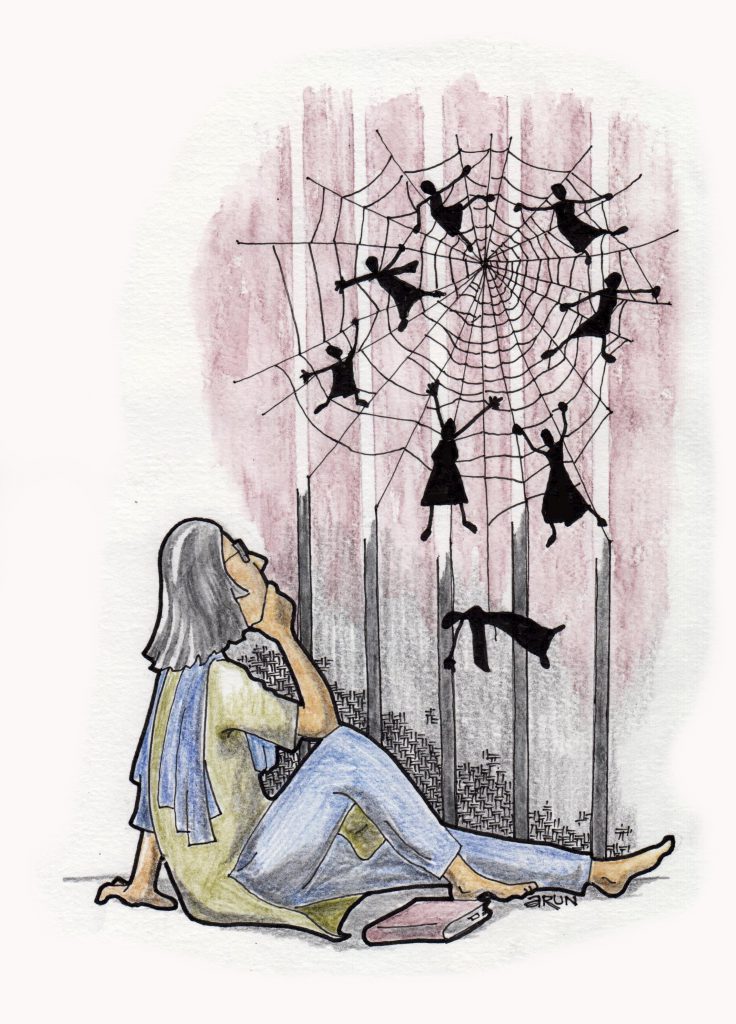

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork.

While we were in jail, Himanta Biswa Sarma, the chief minister of Assam, initiated a campaign (read: crackdown) against child marriage. Instead of formulating programmes to educate the community and facilitate social reforms, he used law enforcement to viciously subjugate the poor, minorities and rural residents, to superimpose modernism through fear and repression.

A large number of women living in prison had been married off between the ages of 12 and 14, and were being held for different crimes, from theft and murder to trafficking drugs and children. I wondered if they were even aware of this other offence that they and their families had committed. If I told them that the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 considers the legal age for marriage for girls as 18, and that attempts were being made to raise it to 21, they would casually reply, whether Hindu or Muslim, “Apne mein aisa hi hota hai”—This is how it happens here.

I would often wonder whether there was any correlation between their crimes and their early marriages, lack of education and social backwardness—and found myself increasingly convinced about it. Take the case of young women incarcerated for murder, for instance. Married off into unfavourable circumstances at the age of 12 or 13, these young women then enter into romantic relationships around the same time most urban, educated teenagers would too, at 17 or 18. The emotions of “love” at this age are so intense, and these young women so vulnerable, that they join their lovers in getting rid of any obstacles without thinking out the consequences. This can lead to the killing of a husband, a spying mother-in-law, even their own offspring who may have chanced upon a sexual encounter.

In Yerawada, a young girl from rural Pune came to jail at the tender age of 19. Pretty in the traditional sense, fair and petite, the girl had pushed her mother-in law off the terrace when she went to dry the washing. The mother-in-law had discovered an extra-marital relationship—a spy, a witness was eliminated, and a life conviction attained.

Another woman left her abusive husband and travelled to Pune with her son to work in a private office and live independently. She ended up killing her son with a cricket bat because he had seen her intimate relations with her lover. With a conviction of ten years, she joined the jail factory because the work helped reduce her prison sentence.

My initial month in Yerawada was supervised by a warder who had finished 22 years of conviction in jail and was soon to be released. Her parents had decided about her marriage when she was just a few months old. They were landed Marathas from Beed in Marathwada, one of the hinterlands of feudal relations and culture. Her husband was a respected school master whose child bride was illiterate and continued to be so all her life.

She loved agricultural work and developed a relationship with a farm worker. One day, when her husband returned from school, he hung up his coat and went to relieve himself. She took his revolver out of his coat pocket and shot him just as he returned. They were both convicted, but her lover worked in the open jail and was released earlier. She had heard that he was working in the Aurangabad MIDC, expected him to receive her at the jail gate after all these years. Ultimately, she had to be kept in a home for destitute women because it was rumoured that her own son would shoot her dead if she showed her face in the village again!

This dare-devil spirit exists among somewhat older women as well, who cannot tolerate an abusive or loveless marriage and oppressive in-laws. It was thus common to see these young, female “teenso-do-waale”—those accused or convicted of murder, under Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code—in the women’s prison, while their “numberkari,” or co-accused, land up in the men’s jail.

The blooming petals of love were crushed and scattered in the quagmire of the law enforcement system. The lovers who wanted to start a new life together are not even allowed to meet in the way that prisoners who are relatives can see each other, such as through video calls or mulakats in jail. Though the jail manual does not prohibit correspondence or communication between co-accused, the prison administration’s moral policing led them to disallow it, preventing the love or any criminal conspiracies hatching in jail.

Needless to say, the women faced grave repercussions for these child-marriage triggered crimes of passion, not just in their conviction, but also arising from the complete lack of support from their families and communities. Who from her parental family or her husband’s or lover’s is going to support her? Who will send her a Money Order so that she can buy special food, fruits or special medicines from the canteen? Who will hire a lawyer for her or bring her updates from the court? Who will pay her surety if she gets bail? If her co-accused is still loyal to her and if he has the means, he may offer a little assistance, but only after his own family has fulfilled his needs.

In Mumbai, there were many women being tried for murder and other crimes who had been victims of child marriage. A Bengali woman from 24 Parganas had been married off when she was just 12, after her husband “spotted” her at 11, and stalked her for a year till she married him. When this 26-year-old came to Byculla Jail, for robbery, she was a single mother with five sons—her eldest son was just 13 years younger than her.

Another Bihari girl had also been married off at the young age of 12, when she came to Mumbai looking for work in a factory. She came to jail in a sari and ghunghat, but left in jeans and a T Shirt. She was falsely accused of forcing her first born—a girl, similarly, just 13 years younger than her, to enter sex work. Another woman facing a similar offence was a grandmother at the age of 35!

To end my anecdotes on a positive note, in Yerawada, there was a kundewali—a sanitation worker—who had been convicted for killing her alcoholic and abusive husband, who heard from her relatives that her 15-year-old daughter was soon to be married. Horrified that her daughter’s life would just be a repeat of her own, this illiterate woman from a “de-notified” tribe appealed to the female jailor to do something. Fortunately, the jailor rang up the police inspector in the concerned village and the marriage was stopped!

While the debate to raise the legal age of marriage for girls from 18 to 21 goes on, these stories from women prisons are a microcosm of the reality—the fate of adolescent girls in the real world!

Related Posts

BK-16 Prison Diaries: Stories of love, murder and child marriage from Shoma Sen’s years in prisons

While we were in jail, Himanta Biswa Sarma, the chief minister of Assam, initiated a campaign (read: crackdown) against child marriage. Instead of formulating programmes to educate the community and facilitate social reforms, he used law enforcement to viciously subjugate the poor, minorities and rural residents, to superimpose modernism through fear and repression.

A large number of women living in prison had been married off between the ages of 12 and 14, and were being held for different crimes, from theft and murder to trafficking drugs and children. I wondered if they were even aware of this other offence that they and their families had committed. If I told them that the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006 considers the legal age for marriage for girls as 18, and that attempts were being made to raise it to 21, they would casually reply, whether Hindu or Muslim, “Apne mein aisa hi hota hai”—This is how it happens here.

I would often wonder whether there was any correlation between their crimes and their early marriages, lack of education and social backwardness—and found myself increasingly convinced about it. Take the case of young women incarcerated for murder, for instance. Married off into unfavourable circumstances at the age of 12 or 13, these young women then enter into romantic relationships around the same time most urban, educated teenagers would too, at 17 or 18. The emotions of “love” at this age are so intense, and these young women so vulnerable, that they join their lovers in getting rid of any obstacles without thinking out the consequences. This can lead to the killing of a husband, a spying mother-in-law, even their own offspring who may have chanced upon a sexual encounter.

In Yerawada, a young girl from rural Pune came to jail at the tender age of 19. Pretty in the traditional sense, fair and petite, the girl had pushed her mother-in law off the terrace when she went to dry the washing. The mother-in-law had discovered an extra-marital relationship—a spy, a witness was eliminated, and a life conviction attained.

Another woman left her abusive husband and travelled to Pune with her son to work in a private office and live independently. She ended up killing her son with a cricket bat because he had seen her intimate relations with her lover. With a conviction of ten years, she joined the jail factory because the work helped reduce her prison sentence.

My initial month in Yerawada was supervised by a warder who had finished 22 years of conviction in jail and was soon to be released. Her parents had decided about her marriage when she was just a few months old. They were landed Marathas from Beed in Marathwada, one of the hinterlands of feudal relations and culture. Her husband was a respected school master whose child bride was illiterate and continued to be so all her life.

She loved agricultural work and developed a relationship with a farm worker. One day, when her husband returned from school, he hung up his coat and went to relieve himself. She took his revolver out of his coat pocket and shot him just as he returned. They were both convicted, but her lover worked in the open jail and was released earlier. She had heard that he was working in the Aurangabad MIDC, expected him to receive her at the jail gate after all these years. Ultimately, she had to be kept in a home for destitute women because it was rumoured that her own son would shoot her dead if she showed her face in the village again!

This dare-devil spirit exists among somewhat older women as well, who cannot tolerate an abusive or loveless marriage and oppressive in-laws. It was thus common to see these young, female “teenso-do-waale”—those accused or convicted of murder, under Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code—in the women’s prison, while their “numberkari,” or co-accused, land up in the men’s jail.

The blooming petals of love were crushed and scattered in the quagmire of the law enforcement system. The lovers who wanted to start a new life together are not even allowed to meet in the way that prisoners who are relatives can see each other, such as through video calls or mulakats in jail. Though the jail manual does not prohibit correspondence or communication between co-accused, the prison administration’s moral policing led them to disallow it, preventing the love or any criminal conspiracies hatching in jail.

Needless to say, the women faced grave repercussions for these child-marriage triggered crimes of passion, not just in their conviction, but also arising from the complete lack of support from their families and communities. Who from her parental family or her husband’s or lover’s is going to support her? Who will send her a Money Order so that she can buy special food, fruits or special medicines from the canteen? Who will hire a lawyer for her or bring her updates from the court? Who will pay her surety if she gets bail? If her co-accused is still loyal to her and if he has the means, he may offer a little assistance, but only after his own family has fulfilled his needs.

In Mumbai, there were many women being tried for murder and other crimes who had been victims of child marriage. A Bengali woman from 24 Parganas had been married off when she was just 12, after her husband “spotted” her at 11, and stalked her for a year till she married him. When this 26-year-old came to Byculla Jail, for robbery, she was a single mother with five sons—her eldest son was just 13 years younger than her.

Another Bihari girl had also been married off at the young age of 12, when she came to Mumbai looking for work in a factory. She came to jail in a sari and ghunghat, but left in jeans and a T Shirt. She was falsely accused of forcing her first born—a girl, similarly, just 13 years younger than her, to enter sex work. Another woman facing a similar offence was a grandmother at the age of 35!

To end my anecdotes on a positive note, in Yerawada, there was a kundewali—a sanitation worker—who had been convicted for killing her alcoholic and abusive husband, who heard from her relatives that her 15-year-old daughter was soon to be married. Horrified that her daughter’s life would just be a repeat of her own, this illiterate woman from a “de-notified” tribe appealed to the female jailor to do something. Fortunately, the jailor rang up the police inspector in the concerned village and the marriage was stopped!

While the debate to raise the legal age of marriage for girls from 18 to 21 goes on, these stories from women prisons are a microcosm of the reality—the fate of adolescent girls in the real world!

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.