BK-16 Prison Diaries: Sagar Gorkhe on his battle to survive Taloja jail’s brutality

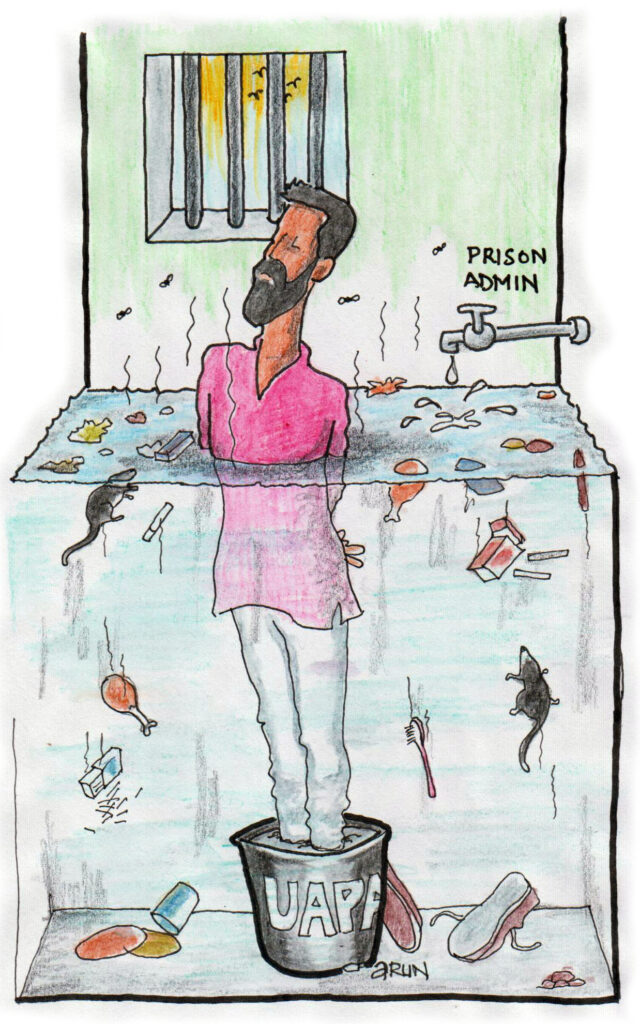

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork. (This piece has been translated from Marathi to English by Vernon Gonsalves, read the original here.)

Address: Taloja Central Prison, Navi Mumbai; Circle Number 2, Barrack Number 4. It’s seven in the evening. The smell of the rancid wet garbage scattered carelessly in the corner of the barrack is troubling me to no end. Over it lies a layer of half-eaten leftovers, bidi butts and green gobs coughed up and spat out by tobacco chewers. Looking at it, I feel like vomiting. The flies buzz around, sit on those spit gobs and, as if on purpose, zero in on me. “Hey, go … go … shoo … go away.” However much I yell to drive them away, they just don’t seem to listen at all. I don’t know what to do.

The doors of all four toilets in the barrack are broken. We have made a screen from sacks, but now there is a new problem. The toilets have become clogged in the rains; one can’t but see the unwanted waste, and also those moustachioed cockroaches. A month ago, I had made an application to the Superintendent to put doors on the toilets, but he said that the Prisoner Welfare Fund did not have sufficient provision to get that done at the time. However, the administration repaired the defective CCTV in an urgent manner.

For a long time, we have been getting only one or two buckets of water to use. The prisoner then is left to solve the riddle of whether to have a bath, or wash clothes. And anyone raising his voice regarding this inevitably face abuse and beatings.

Here, the prisoners get second-rate chapatis (flatbread), tasteless bhaji (vegetables) and insipid dal (lentil soup), which you would not even feed your house dog. Prisoners bet on whether the burnt piece seen floating in the dal is garlic, or some insect; whatever it may be, you have no option but to shove it in your mouth. I find eating here a major struggle.

The prison officers purposely see to it that the standard of the food keeps sliding because then they can sell good food in black to the rich prisoners. There is a shop setup in the prison, which is called a canteen, for the prisoners. Its purpose is to provide daily necessities to the prisoners on a ‘no profit, no loss’ basis. But the jail officials earn in lakhs by selling things at higher prices to the prisoners.

The business of hunger and corruption

Jail officials in Taloja have developed numerous means of earning money. Create an artificial shortage of sleeping rugs and then sell the same for five or ten thousand rupees. Arrange sleeping space for ten to fifteen thousand. If you want to go out of the prison on your court date, you have to give ten thousand; if you want to go to the hospital outside, pay fifteen thousand; pay twenty thousand for a mulakaat—meeting—with anyone of your choice; shell out one lakh for good food for a month. Business in jail runs like this. This way, the rich prisoners can enjoy, but the ordinary prisoners have to suffer a lot, because it is only by stealing from the rations meant for the poorer prisoners that the rich prisoners can be pampered.

From the time I entered prison, I have been taking medication from a psychiatric specialist. But there has been no concrete diagnosis of the mental illness. A long time ago, a so-called psychiatric specialist examined me for just five to ten minutes and gave me some medicines. Here, the crucial psychiatric treatment of counselling is never provided. Only medicines are given, which are always irregular. Whatever they may be, I do not get to sleep at night. It feels as if the hands of the clock have halted at one spot. Even if I sleep, I get up all of a sudden. My head keeps hurting as if it’s being struck by a hammer.

Outside the prison, I was known as a cultural activist, a rebel singer, but I do not sing in here. My mother tells me to keep singing, but I feel very suffocated. Mother says in her letters, “You are my strong son fighting for the truth, and I am proud of you”. But I have not yet told her that I am very troubled and that I am taking psychiatric treatment. She would feel severe tension. The doctor tells me to meditate, but there isn’t the slightest peace here. Forty-eight prisoners are packed into a barrack meant for eighteen. What peace can there be?

These days, due to the monsoons, the barracks stay very damp. Many got conjunctivitis, with sticky yellow liquid leaking from their eyes. Many have malaria, they shiver with fever. You only get one dirty white sheet to cover yourself. Those with feverish chills have to make do by covering themselves with these dirty sheets. When they lie in a row taking warmth from each other’s bodies, they seem like a line of corpses laid out.

Many have a funereal gaze fixed on the creaking and groaning fans whirling above. Maybe they are planning to hang themselves from it. Sometimes I too think like that. Finish it all off once and for all with a single stroke. But mother and her face come to my mind. I then have to control myself. Controlling and holding myself together; four long years have passed.

A fight for dignity behind bars

Much has become clear to people about the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case applied on me. Much has been exposed through books, articles, and protests. The Elgar Parishad, held under the chairmanship of a retired Supreme Court judge, following due legal process and in accordance with the right to express dissent guaranteed by the Constitution, has been painted as a big conspiracy. This false case has been set up through a collaboration between the police and the ruling sections.

It’s like a big kadhai—a wok. Beneath it is the fire, boiling oil in the kadhai. And one by one, we are being thrown into it. This is the format of this case. With the devious aim of weakening the people’s movement by making them rot for years in prison, somehow or the other, something was fabricated against 16 persons from various states and they were thrown into prison. People have given us prisoners the title of BK-16 (Bhima Koregaon 16). Some of us have been languishing in prison for six years, some five, and some for four years.

At present, we are struggling to improve the deteriorating quality of prison food and stop the corruption in canteen sales. When we made applications regarding this, the senior jailor called us to his office and threatened us. The fact is that, due to the high-profile nature of the Elgar case, the Hitlerite prison officials cannot beat us up directly. Had it been someone else, he would have been given naalbandhi—a severe beating on the soles of the feet—and thrown to some corner. Since they cannot beat us, various tactics are being used against us. A negative atmosphere is being fomented by sowing mistrust among other inmates through false stories against us. But they have not succeeded in this effort because the Elgar prisoners have built a good image among their fellow prisoners by practising honesty and struggling against injustice.

At this point, I feel it necessary to clearly mention one thing: here, the voice of every prisoner is suppressed in the most savage manner. The slightest whisper of a complaint is throttled. Any complaint application is torn and thrown away. “You seem to be getting too smart? Stay within limits! Don’t make too many applications, it will prove costly! Throw him out of the Circle! Call an escort party to transfer him to another jail! Stop his mulakaats, stop his money orders, stop his court dates, stop everything! Send a report to the court about his indisciplined behaviour!” It is in this way that the act of raising complaints is crushed by a flood of threats. No complaint of a prisoner is ever taken seriously. The complainant, however, is seriously targeted.

The prison behaves like the Roman slave system. It behaves perversely like the caste system that boycotts Dalits and rejects their humanity. The prison is discriminatory and profit-centred like the capitalist system. Terror is created by snapping at, shouting at and abusing the prisoners, so that they may remain with their heads held low and live like slaves with a submissive mentality. At the prison’s red gate, at the very first point of entry, the prisoner is stripped completely naked. Despite there being metal detectors, scanning machines, and other such modern devices, the body search is done by the jail staff and officers in an inhuman, depraved manner. The mentality of the prison officers and staff is feudal; it is deliberately made feudal because the prison itself runs like a feudal kingdom.

It’s not tolerated if prisoners stand in front of prison officers and the superintendent with their chappals—slippers—on. The prisoner has to remove his chappals while entering an office where the officer sits with his shoes on. There are many perverse unwritten rules such as bowing and speaking in a low voice when speaking to the superintendent. Once, when I went to the prison superintendent to complain about a jail official, when they tried to force us to remove my chappals in the rain and stand in the muck before the superintendent, Sudhir Dhawale and I opposed this strongly. I said, “This is a government office, not the manor of the Patil (lord). Why should we stand barefoot before you? You are practising a form of caste system here.” It was on that very day that we had to bear the result of my protestations. We ‘Elgarwallein’ were lifted and thrown into the cells of the Anda Circle, where we could not even see a simple green leaf of a tree. We were given the punishment of being separated from other prisoners. It was the punishment for registering our protest, for resisting.

They feel terribly hurt when we ‘Elgarwallein’ oppose their illogical rules. Then they start acting vengeful with us. Letters sent by family members and lawyers suddenly disappear; unreasonable restrictions are applied out of the blue to deny a meeting with a relative who has come for a mulakaat; spectacles sent to Gautam Navlakha by his family by post are sent back; Father Stan Swamy is denied a straw sipper; Surendra Gadling’s Ayurvedic medicines are blocked; a mosquito net being used by Ramesh Gaichor is seized in the midst of the monsoons; Elgar prisoners are stopped from using political and legal books. These are just some of the calculated ways they create obstacles, with a deliberate and malicious intent. In response, we must repeatedly rise up to protest these actions.

Polarisation, persecution, and perseverance

The atmosphere in the prison has been extremely polluted for the last ten years. Ever since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014, the politics of religious hatred has been pandered to and its results can be observed most clearly within the prison itself. The Sanghi narrative behind building the Ram Mandir is on the lips of prisoners who do not even know how to read or write. Religious polarisation in the prisons is on the rise. In a single barrack, there is a mandir galli (temple lane) and a masjid galli (mosque lane). The division created outside has also entered the prison. And the jail administration, rather than controlling, is only encouraging it.

The red carpet is laid out for organisations that are associated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and share a similar ideology. Organisations like the Gayatri Parivar and Swadhyay Parivar use the banner of religious discourses to sow religious supremacist views among the prisoners and introduce the slow poison of their fundamentalism. Bhajans—Hindu devotional songs—are blared through loudspeakers every day. While prisoners don’t even get simple access to legal aid, the Bhagawad Gita is played online every morning. We still try, to the extent possible, to conscientise the inmates with the constitutional values of equality, secularism and democracy and provide them with some legal help. At the same time, the jail administration wants to keep the prisoners busy in religious and caste issues.

The prison administration gets quite irritated by the other prisoners’ positive attitude towards us. Then they try to malign us. They say, “Elgarwallein are anti-nationals, don’t fall into their trap, or you will get spoilt.” The prison system seems to have messed up the concepts of improvement and getting spoilt. The prison has been called a correctional home and the prison administration’s banner of reform and rehabilitation is flaunted everywhere. But there is an extreme lack of understanding about what is actually meant by prisoner reformation. A question constantly worrying the prisoner here, who has landed in prison because he has broken the law, is this: Why is no one there to punish the prison administration, which itself acts illegally, which acts corruptly and breaks the law?

There is no fear of any machinery or any government institution in the prison. That is why this prison administration has for years been completely free to treat the prisoners in an inhumane manner. The question is who in this prison—ornamentally named a correctional home—needs to be corrected or reformed? Is it the person who has been stamped a criminal, or the administrative machinery and state machinery that acts like one? I think that it is actually the jail officials, casually carrying on with their casteist, feudal, profit-mongering, and corrupt mentality, who need to be reformed.

Daily, lying immobile on that two-by six-feet dhurrie—a thin rug—that passes off as a mattress, the prisoner digs deep into the recesses of his inner being. Stirring up the sediments settled in the pool of memories, problems, pain, responsibilities and worries, he keeps bringing them up onto the mind’s agenda. Someone keeps sobbing, shedding tears over his small children; another feels helpless over his inability to help his son who has come of age or his mother who needs a cataract operation; someone is distressed by the debilitating pain of separation from a lover or a spouse, while another is deep in thought about his life and existence.

From the midst of such a muted tumult, when the dam of pent-up pain bursts forth in song, the prison manual harshly scolds, “Beware! Keep quiet! Singing in jail is an offence.” The fact is that I have not sung here for a long time. My mother says keep singing, but I feel very suffocated. When someone gives me advice that a revolutionary should write and read, should scribble out books in prison, one should be like Bhagat Singh, Birsa, Gandhi, etc., then I feel quite distressed. I feel like telling them to come here and show their revolutionary self, but I do not say any such thing because they don’t mean ill. But the situation is terrible. If I write at all, I do it in an outburst of pain and sorrow. But these days I write very little. While summing up the experiences of eight long years of prison life in two UAPA cases, I finally wrote:

Jail has snatched my everything

Jail has snatched my everything

Has snatched those playful days of youth

Has snatched that changing destiny

Jail has snatched my everything

My village, its bye lanes, my breath, my liberty

From my house the bread, from my sister matrimony

Has snatched my own, has snatched those visions

Has snatched my stories, also their narrations

I’d open my heart, I thought I’d weep

But even the tears flowing down were snatched

I thought I could live on their support deep

But my friends were snatched, and my love too was snatched.

Prison has created breaches in my life; my world, my relationships have been destroyed. It has made my future very uncertain. The sorrow and pain are very corrosive. Here, at every step, one recognises one’s abilities and limitations. I have great love for my principles, my thoughts, my movement and my songs and it is because of this love that I have again been imprisoned. When the shrewd officers of the National Investigating Agency tried to get me and Ramesh to give a false statement, first through inducement and then through threat, we knew then itself that we were taking a big risk. Even though we knew that our stand would land us in a prison cell, we stood by it. We rejected the police’s offer and accepted to go to prison. And we do not have the slightest regret about this till today.

May your pricy gift

Be for you, compliments to you

For my blood still simmers

with the heat of battle

Freedom is the price to be paid

for the protection of principles

You give me imprisonment or

you give me the sentence of death.

I still stand today by the political understanding with which I wrote these lines in the past. Repression brings about exhaustion. And it is really a fact that today I am exhausted, but I am not defeated. The prison is trying to break me, and I the prison. I do not know how this struggle will end, but I do know that I will have the satisfaction of the good fight. The Elgar Parishad case is driven by political motives. This case is a part of the repression of people. Therefore, there is no option but to fight with whatever weapons we get, in whatever way we can.

Repression and resistance in prison

The prison has become an absolutely essential part of the BJP’s system based on exploitation. Today, the opposition party, necessary for a democracy, is crushed and tied in prison. Under the Modi government, the investigative machinery is relentlessly persecuting the opposition and throwing them into prison. The fear of prison is so high in the opposition that now they are siding with those in power. Social movements and activists are afraid. The prison has become the venomous weapon. In such a situation, we have accepted prison rather than a secure life, rather than compromise.

Therefore, no matter how stressful the insults, neglect, pain and obstacles, we ‘Elgarwallein’ are standing and fighting the prison atrocities through judicial satyagrahi means. When I had gone on hunger strike for eight days demanding medical facilities for Elgar prisoners, an end to our letters being shown to the investigative machinery, for a phone facility, for a rightful share of water, for a rest house for relatives coming for mulakaat, the prison administration did not move at all until the courts and media took note. Our associates in the movement had highlighted the agitation launched in the jail and the media covered it, due to which the administration had to bend.

No struggle in the prison can be pushed ahead without outside support. The path of hunger strikes and non-cooperation can be successful in prison only with outside support. Today, the aura of publicity around the Elgar case and the support from family of friends in the movement gives us the strength to stay alive and struggle inside. If we did not have these dear friends with us, it would have been very difficult to stay alive. The judicial struggle would have been very difficult without the legal team.

The purpose of the prison is to dissuade and discourage me from sticking to my ideals and to break me, and yet, I have not been broken. The desire for freedom is growing sharper. These years have passed in dreams of what to do after my release. I want to live free with my lover, eat the methi bhaji (fenugreek leaves) made by my mother, and catch the high note again, I want to slap the duff. It has been four years in prison. When will the red gate open for our freedom? Like a caged bird, I wait.

This piece has been translated from Marathi to English by Vernon Gonsalves, read the original here. Read our profile of Sagar Gorkhe from the Polis Project’s Profiles of Dissent series here.

Address: Taloja Central Prison, Navi Mumbai; Circle Number 2, Barrack Number 4. It’s seven in the evening. The smell of the rancid wet garbage scattered carelessly in the corner of the barrack is troubling me to no end. Over it lies a layer of half-eaten leftovers, bidi butts and green gobs coughed up and spat out by tobacco chewers. Looking at it, I feel like vomiting. The flies buzz around, sit on those spit gobs and, as if on purpose, zero in on me. “Hey, go … go … shoo … go away.” However much I yell to drive them away, they just don’t seem to listen at all. I don’t know what to do.

The doors of all four toilets in the barrack are broken. We have made a screen from sacks, but now there is a new problem. The toilets have become clogged in the rains; one can’t but see the unwanted waste, and also those moustachioed cockroaches. A month ago, I had made an application to the Superintendent to put doors on the toilets, but he said that the Prisoner Welfare Fund did not have sufficient provision to get that done at the time. However, the administration repaired the defective CCTV in an urgent manner.

For a long time, we have been getting only one or two buckets of water to use. The prisoner then is left to solve the riddle of whether to have a bath, or wash clothes. And anyone raising his voice regarding this inevitably face abuse and beatings.

Here, the prisoners get second-rate chapatis (flatbread), tasteless bhaji (vegetables) and insipid dal (lentil soup), which you would not even feed your house dog. Prisoners bet on whether the burnt piece seen floating in the dal is garlic, or some insect; whatever it may be, you have no option but to shove it in your mouth. I find eating here a major struggle.

The prison officers purposely see to it that the standard of the food keeps sliding because then they can sell good food in black to the rich prisoners. There is a shop setup in the prison, which is called a canteen, for the prisoners. Its purpose is to provide daily necessities to the prisoners on a ‘no profit, no loss’ basis. But the jail officials earn in lakhs by selling things at higher prices to the prisoners.

The business of hunger and corruption

Jail officials in Taloja have developed numerous means of earning money. Create an artificial shortage of sleeping rugs and then sell the same for five or ten thousand rupees. Arrange sleeping space for ten to fifteen thousand. If you want to go out of the prison on your court date, you have to give ten thousand; if you want to go to the hospital outside, pay fifteen thousand; pay twenty thousand for a mulakaat—meeting—with anyone of your choice; shell out one lakh for good food for a month. Business in jail runs like this. This way, the rich prisoners can enjoy, but the ordinary prisoners have to suffer a lot, because it is only by stealing from the rations meant for the poorer prisoners that the rich prisoners can be pampered.

From the time I entered prison, I have been taking medication from a psychiatric specialist. But there has been no concrete diagnosis of the mental illness. A long time ago, a so-called psychiatric specialist examined me for just five to ten minutes and gave me some medicines. Here, the crucial psychiatric treatment of counselling is never provided. Only medicines are given, which are always irregular. Whatever they may be, I do not get to sleep at night. It feels as if the hands of the clock have halted at one spot. Even if I sleep, I get up all of a sudden. My head keeps hurting as if it’s being struck by a hammer.

Outside the prison, I was known as a cultural activist, a rebel singer, but I do not sing in here. My mother tells me to keep singing, but I feel very suffocated. Mother says in her letters, “You are my strong son fighting for the truth, and I am proud of you”. But I have not yet told her that I am very troubled and that I am taking psychiatric treatment. She would feel severe tension. The doctor tells me to meditate, but there isn’t the slightest peace here. Forty-eight prisoners are packed into a barrack meant for eighteen. What peace can there be?

These days, due to the monsoons, the barracks stay very damp. Many got conjunctivitis, with sticky yellow liquid leaking from their eyes. Many have malaria, they shiver with fever. You only get one dirty white sheet to cover yourself. Those with feverish chills have to make do by covering themselves with these dirty sheets. When they lie in a row taking warmth from each other’s bodies, they seem like a line of corpses laid out.

Many have a funereal gaze fixed on the creaking and groaning fans whirling above. Maybe they are planning to hang themselves from it. Sometimes I too think like that. Finish it all off once and for all with a single stroke. But mother and her face come to my mind. I then have to control myself. Controlling and holding myself together; four long years have passed.

A fight for dignity behind bars

Much has become clear to people about the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case applied on me. Much has been exposed through books, articles, and protests. The Elgar Parishad, held under the chairmanship of a retired Supreme Court judge, following due legal process and in accordance with the right to express dissent guaranteed by the Constitution, has been painted as a big conspiracy. This false case has been set up through a collaboration between the police and the ruling sections.

It’s like a big kadhai—a wok. Beneath it is the fire, boiling oil in the kadhai. And one by one, we are being thrown into it. This is the format of this case. With the devious aim of weakening the people’s movement by making them rot for years in prison, somehow or the other, something was fabricated against 16 persons from various states and they were thrown into prison. People have given us prisoners the title of BK-16 (Bhima Koregaon 16). Some of us have been languishing in prison for six years, some five, and some for four years.

At present, we are struggling to improve the deteriorating quality of prison food and stop the corruption in canteen sales. When we made applications regarding this, the senior jailor called us to his office and threatened us. The fact is that, due to the high-profile nature of the Elgar case, the Hitlerite prison officials cannot beat us up directly. Had it been someone else, he would have been given naalbandhi—a severe beating on the soles of the feet—and thrown to some corner. Since they cannot beat us, various tactics are being used against us. A negative atmosphere is being fomented by sowing mistrust among other inmates through false stories against us. But they have not succeeded in this effort because the Elgar prisoners have built a good image among their fellow prisoners by practising honesty and struggling against injustice.

At this point, I feel it necessary to clearly mention one thing: here, the voice of every prisoner is suppressed in the most savage manner. The slightest whisper of a complaint is throttled. Any complaint application is torn and thrown away. “You seem to be getting too smart? Stay within limits! Don’t make too many applications, it will prove costly! Throw him out of the Circle! Call an escort party to transfer him to another jail! Stop his mulakaats, stop his money orders, stop his court dates, stop everything! Send a report to the court about his indisciplined behaviour!” It is in this way that the act of raising complaints is crushed by a flood of threats. No complaint of a prisoner is ever taken seriously. The complainant, however, is seriously targeted.

The prison behaves like the Roman slave system. It behaves perversely like the caste system that boycotts Dalits and rejects their humanity. The prison is discriminatory and profit-centred like the capitalist system. Terror is created by snapping at, shouting at and abusing the prisoners, so that they may remain with their heads held low and live like slaves with a submissive mentality. At the prison’s red gate, at the very first point of entry, the prisoner is stripped completely naked. Despite there being metal detectors, scanning machines, and other such modern devices, the body search is done by the jail staff and officers in an inhuman, depraved manner. The mentality of the prison officers and staff is feudal; it is deliberately made feudal because the prison itself runs like a feudal kingdom.

It’s not tolerated if prisoners stand in front of prison officers and the superintendent with their chappals—slippers—on. The prisoner has to remove his chappals while entering an office where the officer sits with his shoes on. There are many perverse unwritten rules such as bowing and speaking in a low voice when speaking to the superintendent. Once, when I went to the prison superintendent to complain about a jail official, when they tried to force us to remove my chappals in the rain and stand in the muck before the superintendent, Sudhir Dhawale and I opposed this strongly. I said, “This is a government office, not the manor of the Patil (lord). Why should we stand barefoot before you? You are practising a form of caste system here.” It was on that very day that we had to bear the result of my protestations. We ‘Elgarwallein’ were lifted and thrown into the cells of the Anda Circle, where we could not even see a simple green leaf of a tree. We were given the punishment of being separated from other prisoners. It was the punishment for registering our protest, for resisting.

They feel terribly hurt when we ‘Elgarwallein’ oppose their illogical rules. Then they start acting vengeful with us. Letters sent by family members and lawyers suddenly disappear; unreasonable restrictions are applied out of the blue to deny a meeting with a relative who has come for a mulakaat; spectacles sent to Gautam Navlakha by his family by post are sent back; Father Stan Swamy is denied a straw sipper; Surendra Gadling’s Ayurvedic medicines are blocked; a mosquito net being used by Ramesh Gaichor is seized in the midst of the monsoons; Elgar prisoners are stopped from using political and legal books. These are just some of the calculated ways they create obstacles, with a deliberate and malicious intent. In response, we must repeatedly rise up to protest these actions.

Polarisation, persecution, and perseverance

The atmosphere in the prison has been extremely polluted for the last ten years. Ever since the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power in 2014, the politics of religious hatred has been pandered to and its results can be observed most clearly within the prison itself. The Sanghi narrative behind building the Ram Mandir is on the lips of prisoners who do not even know how to read or write. Religious polarisation in the prisons is on the rise. In a single barrack, there is a mandir galli (temple lane) and a masjid galli (mosque lane). The division created outside has also entered the prison. And the jail administration, rather than controlling, is only encouraging it.

The red carpet is laid out for organisations that are associated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and share a similar ideology. Organisations like the Gayatri Parivar and Swadhyay Parivar use the banner of religious discourses to sow religious supremacist views among the prisoners and introduce the slow poison of their fundamentalism. Bhajans—Hindu devotional songs—are blared through loudspeakers every day. While prisoners don’t even get simple access to legal aid, the Bhagawad Gita is played online every morning. We still try, to the extent possible, to conscientise the inmates with the constitutional values of equality, secularism and democracy and provide them with some legal help. At the same time, the jail administration wants to keep the prisoners busy in religious and caste issues.

The prison administration gets quite irritated by the other prisoners’ positive attitude towards us. Then they try to malign us. They say, “Elgarwallein are anti-nationals, don’t fall into their trap, or you will get spoilt.” The prison system seems to have messed up the concepts of improvement and getting spoilt. The prison has been called a correctional home and the prison administration’s banner of reform and rehabilitation is flaunted everywhere. But there is an extreme lack of understanding about what is actually meant by prisoner reformation. A question constantly worrying the prisoner here, who has landed in prison because he has broken the law, is this: Why is no one there to punish the prison administration, which itself acts illegally, which acts corruptly and breaks the law?

There is no fear of any machinery or any government institution in the prison. That is why this prison administration has for years been completely free to treat the prisoners in an inhumane manner. The question is who in this prison—ornamentally named a correctional home—needs to be corrected or reformed? Is it the person who has been stamped a criminal, or the administrative machinery and state machinery that acts like one? I think that it is actually the jail officials, casually carrying on with their casteist, feudal, profit-mongering, and corrupt mentality, who need to be reformed.

Daily, lying immobile on that two-by six-feet dhurrie—a thin rug—that passes off as a mattress, the prisoner digs deep into the recesses of his inner being. Stirring up the sediments settled in the pool of memories, problems, pain, responsibilities and worries, he keeps bringing them up onto the mind’s agenda. Someone keeps sobbing, shedding tears over his small children; another feels helpless over his inability to help his son who has come of age or his mother who needs a cataract operation; someone is distressed by the debilitating pain of separation from a lover or a spouse, while another is deep in thought about his life and existence.

From the midst of such a muted tumult, when the dam of pent-up pain bursts forth in song, the prison manual harshly scolds, “Beware! Keep quiet! Singing in jail is an offence.” The fact is that I have not sung here for a long time. My mother says keep singing, but I feel very suffocated. When someone gives me advice that a revolutionary should write and read, should scribble out books in prison, one should be like Bhagat Singh, Birsa, Gandhi, etc., then I feel quite distressed. I feel like telling them to come here and show their revolutionary self, but I do not say any such thing because they don’t mean ill. But the situation is terrible. If I write at all, I do it in an outburst of pain and sorrow. But these days I write very little. While summing up the experiences of eight long years of prison life in two UAPA cases, I finally wrote:

Jail has snatched my everything

Jail has snatched my everything

Has snatched those playful days of youth

Has snatched that changing destiny

Jail has snatched my everything

My village, its bye lanes, my breath, my liberty

From my house the bread, from my sister matrimony

Has snatched my own, has snatched those visions

Has snatched my stories, also their narrations

I’d open my heart, I thought I’d weep

But even the tears flowing down were snatched

I thought I could live on their support deep

But my friends were snatched, and my love too was snatched.

Prison has created breaches in my life; my world, my relationships have been destroyed. It has made my future very uncertain. The sorrow and pain are very corrosive. Here, at every step, one recognises one’s abilities and limitations. I have great love for my principles, my thoughts, my movement and my songs and it is because of this love that I have again been imprisoned. When the shrewd officers of the National Investigating Agency tried to get me and Ramesh to give a false statement, first through inducement and then through threat, we knew then itself that we were taking a big risk. Even though we knew that our stand would land us in a prison cell, we stood by it. We rejected the police’s offer and accepted to go to prison. And we do not have the slightest regret about this till today.

May your pricy gift

Be for you, compliments to you

For my blood still simmers

with the heat of battle

Freedom is the price to be paid

for the protection of principles

You give me imprisonment or

you give me the sentence of death.

I still stand today by the political understanding with which I wrote these lines in the past. Repression brings about exhaustion. And it is really a fact that today I am exhausted, but I am not defeated. The prison is trying to break me, and I the prison. I do not know how this struggle will end, but I do know that I will have the satisfaction of the good fight. The Elgar Parishad case is driven by political motives. This case is a part of the repression of people. Therefore, there is no option but to fight with whatever weapons we get, in whatever way we can.

Repression and resistance in prison

The prison has become an absolutely essential part of the BJP’s system based on exploitation. Today, the opposition party, necessary for a democracy, is crushed and tied in prison. Under the Modi government, the investigative machinery is relentlessly persecuting the opposition and throwing them into prison. The fear of prison is so high in the opposition that now they are siding with those in power. Social movements and activists are afraid. The prison has become the venomous weapon. In such a situation, we have accepted prison rather than a secure life, rather than compromise.

Therefore, no matter how stressful the insults, neglect, pain and obstacles, we ‘Elgarwallein’ are standing and fighting the prison atrocities through judicial satyagrahi means. When I had gone on hunger strike for eight days demanding medical facilities for Elgar prisoners, an end to our letters being shown to the investigative machinery, for a phone facility, for a rightful share of water, for a rest house for relatives coming for mulakaat, the prison administration did not move at all until the courts and media took note. Our associates in the movement had highlighted the agitation launched in the jail and the media covered it, due to which the administration had to bend.

No struggle in the prison can be pushed ahead without outside support. The path of hunger strikes and non-cooperation can be successful in prison only with outside support. Today, the aura of publicity around the Elgar case and the support from family of friends in the movement gives us the strength to stay alive and struggle inside. If we did not have these dear friends with us, it would have been very difficult to stay alive. The judicial struggle would have been very difficult without the legal team.

The purpose of the prison is to dissuade and discourage me from sticking to my ideals and to break me, and yet, I have not been broken. The desire for freedom is growing sharper. These years have passed in dreams of what to do after my release. I want to live free with my lover, eat the methi bhaji (fenugreek leaves) made by my mother, and catch the high note again, I want to slap the duff. It has been four years in prison. When will the red gate open for our freedom? Like a caged bird, I wait.

This piece has been translated from Marathi to English by Vernon Gonsalves, read the original here. Read our profile of Sagar Gorkhe from the Polis Project’s Profiles of Dissent series here.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.