BK-16 Prison Diaries: Rupali Jadhav travels ten hours for fleeting exchanges with Jyoti Jagtap

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork. (This piece has been translated into English by Unnayan Kumar, read the original in Hindi here.)

This is the story of that day, when Jyoti was supposed to meet us, but did not show up. Two other members of Kabir Kala Manch, Ramesh and Sagar, had already been arrested in connection with the Bhima Koregaon case, and the NIA had summoned Jyoti to Mumbai for questioning for the third time. The next day, on 8 September 2020, Jyoti was supposed to meet me and some of our sathis, or friends, at Sarasbaug in Pune. We waited for her for a long time. Her phone was unreachable. I became anxious because she is usually very punctual and disciplined, and I told the others that she never takes this long. Only after I started searching for her did I receive the call. “We are calling from Pune ATS. Jyoti Jagtap has been arrested. You can come here to collect her keys and belongings.”

After making us wait for a long time outside the Anti-Terrorism Squad’s office, in Shivajinagar, they called me inside. “What happened?” I asked Jyoti, as soon as I met her. She was on her way to meet us, Jyoti said. As soon as she left the house, she noticed some suspicious people standing nearby who started following her vehicle. At the next signal, a female police officer got out of a police van, stopped her two-wheeler, and said, “You are under arrest.” Hearing this, all I could think was how dramatic it was!

Even though Jyoti had responded by email to everything the police asked, she was still arrested as if she was some notorious criminal or gangster. I smiled and told Jyoti, “Don’t stress too much. Take care of yourself in jail. Stay strong mentally and physically. Continue your studies. I’ll send all your counselling books. We’ll arrange money orders for you from time to time.” We could only talk briefly. Her belongings were handed over to me, and we smiled and hugged each other. I assured her that I would see her again soon and left. A female officer from the ATS was watching us with surprise. Her expression suggested that she was wondering why there was no fear on our faces.

After Jyoti’s arrest, the COVID pandemic began. Our sathis were no longer presented in court, so we could not meet them. Since then, all my meetings with Jyoti have taken place at the Mumbai sessions court. I’ve always been curious about what happens inside the jail and about their daily routines. But there’s no time for such discussions on court dates. Our primary concern is to know about their well-being, their needs, whether they received the money order, their health issues, news from the outside world, and updates about home. Inmates are usually very interested in knowing what’s happening outside. It gives them a sense of belonging. Considering that these people, until recently, were free as birds and are now confined to a room, their desire to know about the world outside is utterly natural.

Whether it is the BK-16 case or the old UAPA case against the Kabir Kala Manch, I had grown quite irritated with the entire system of courts, police, lawyers, and judges, having dealt with it since 2013. The primary reason is that when we travel to another city, it feels different from our own—for instance, the intense heat in Mumbai and how it leads to dehydration and exhaustion. For three or four years, I couldn’t understand why I felt irritated as soon as I arrived in Mumbai. But now I realise that with the change in environment, we need to adapt not only mentally but physically as well. So now, I pay attention to issues like dehydration whenever I go to meet my sathis on court dates. Besides the heat, Mumbai has a crowded and hectic atmosphere, which is also evident in the court. It’s always swarmed with the prisoners, their relatives, police, military, and lawyers. Amid all the commotion, a tea vendor serves tea and water to everyone in the court premises.

Nothing is ever certain about court dates. Will our imprisoned sathis be produced in court or not? If they are, how long will they be in court? How many will be brought? On 3 June this year, when I went to Mumbai from Pune, not all our sathis were brought in due to a shortage of guards because of the elections. So, nothing is definite. We always have to check with the lawyer. Sometimes we find out upon arrival that they won’t be brought in that day. Even if they are brought in, there is no guarantee of how long they will be in the court. Sometimes they may be there for the entire day, and sometimes they might be around for just 10 minutes or half an hour.

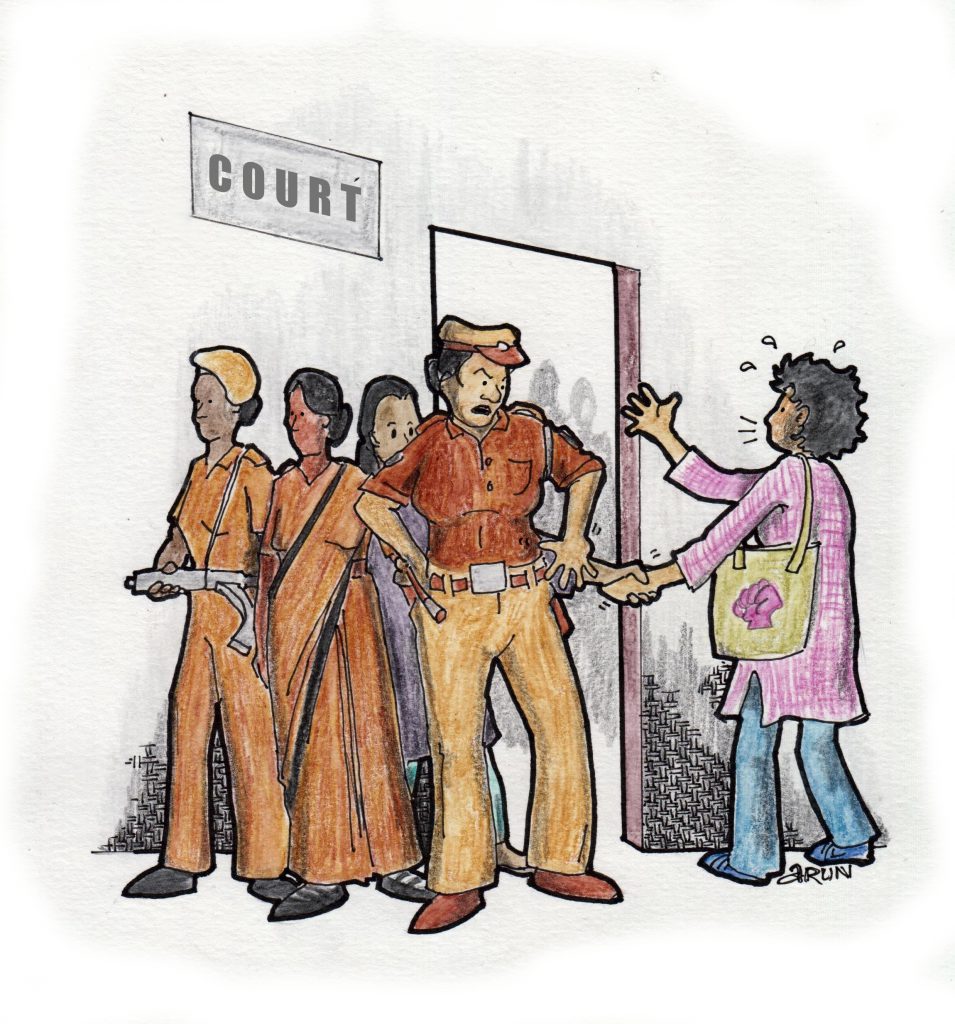

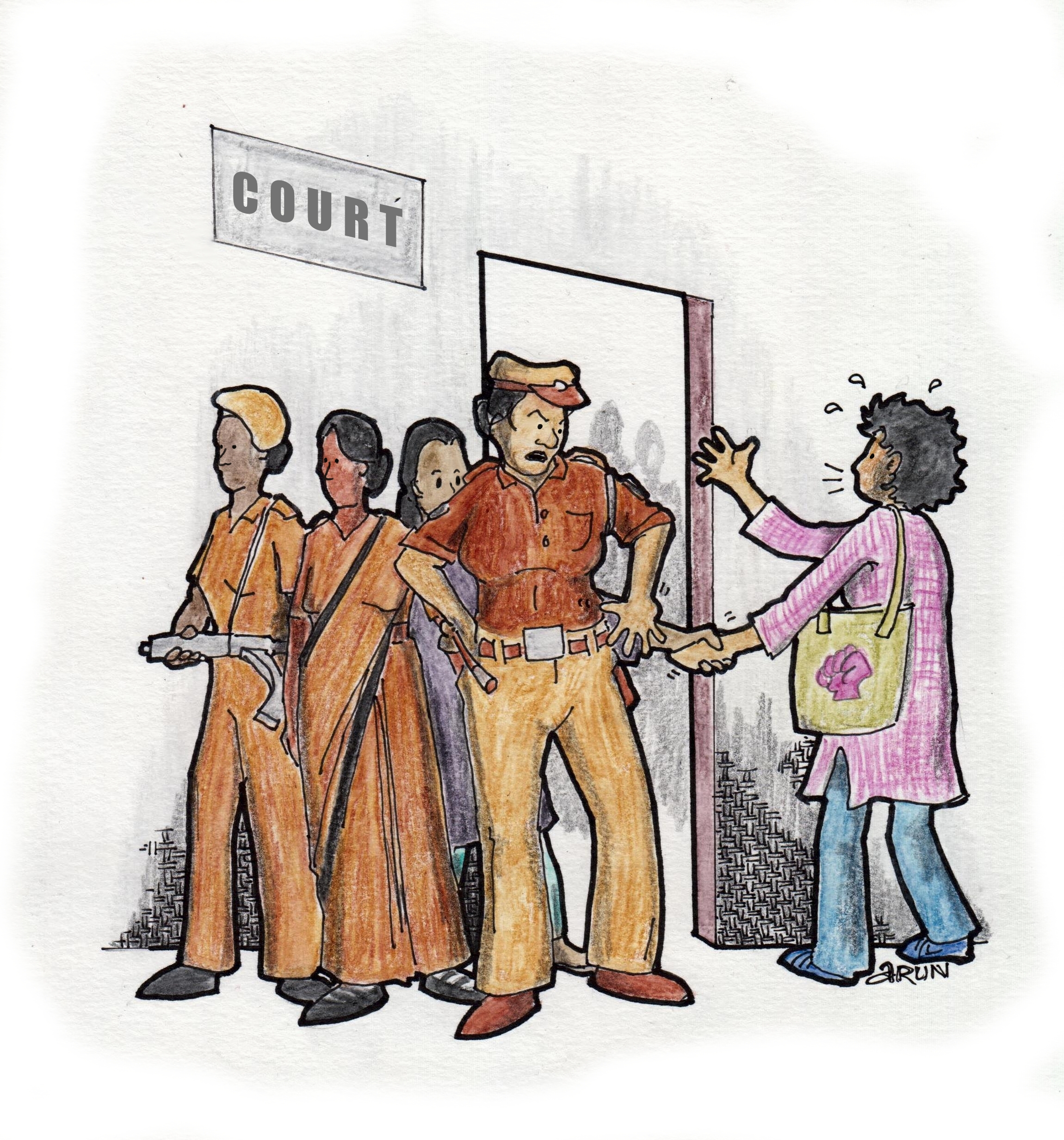

On the 3rd, almost all the cars and trains were delayed due to the election. When we got off the train and boarded a taxi, we received a message from the lawyer saying, “Jyoti has arrived at the court.” Five minutes later, another text followed: “You need to come as soon as possible because they are taking Jyoti away.” We wondered how it was possible that they could take her away in just ten minutes. These kinds of questions often run through our minds. That day, we somehow managed to get to the court, shook hands with her, and asked about her well-being. Then, within ten minutes, the police took her away. Despite many requests from us, the lawyers, and Jyoti herself, the police did not budge at all.

“We have come from Pune,” I said. “Just give us a few more minutes.” But they refused. So even after a five-hour journey to get there and another five-hour journey back, you can’t be sure of a meeting. We also have to take a whole day off for a court date, which includes the cost of travel and food. We have been through this so many times that we now understand how the system always dictates what we should and shouldn’t do. It’s tough to decide whether to feel happy about meeting our sathis or sad about meeting them for just ten minutes after a ten-hour journey.

Once, I asked Jyoti about her daily routine in jail. She told me that she reads books, exercises, is learning English, and also counsels other women. She helps them as much as possible with their legal processes. Last time, she asked me to find out about the organisations that help women rebuild their lives after completing their prison term. Jyoti’s activism continues even inside the jail, because there are people who need help both inside and outside.

Jyoti is now allowed to make video calls to her family, so we don’t usually talk about her parents or family anymore, since she can speak to them directly. Occasionally, I speak to Jyoti’s mother on the phone. She always asks me what wrong Jyoti committed, and when will she get bail. I know I have answered this question a hundred times before, but still, I explain everything to her each time. I try to help her understand, from her perspective, the concept of satta (power), desh (country), deshdroh (treason), the issues of jal-jungle-jameen (water-forest-land), and what it means to be an activist and an artist.

We are all political activists, so we mostly talk about politics, the outside environment, organisations, rallies, movements, and the struggles of other activists. Jyoti has applied for bail. There is a chance that she might get it. We discussed that if she gets bail, we’ll need two people and all their documents ready in time for her surety. I told her that I am continuously trying to find such people. I assured her that I am looking for the people who can help her lead a better life once she gets out and support her counselling centre as well. I told her that if there is a change in the government, there is a possibility that she and all the BK-16 might get bail.

We talked about all these things as we walked. The police were taking her away. A barricade ahead stopped us. From there, the police put Jyoti into a vehicle parked a short distance away and took her back to jail.

Related Posts

BK-16 Prison Diaries: Rupali Jadhav travels ten hours for fleeting exchanges with Jyoti Jagtap

This is the story of that day, when Jyoti was supposed to meet us, but did not show up. Two other members of Kabir Kala Manch, Ramesh and Sagar, had already been arrested in connection with the Bhima Koregaon case, and the NIA had summoned Jyoti to Mumbai for questioning for the third time. The next day, on 8 September 2020, Jyoti was supposed to meet me and some of our sathis, or friends, at Sarasbaug in Pune. We waited for her for a long time. Her phone was unreachable. I became anxious because she is usually very punctual and disciplined, and I told the others that she never takes this long. Only after I started searching for her did I receive the call. “We are calling from Pune ATS. Jyoti Jagtap has been arrested. You can come here to collect her keys and belongings.”

After making us wait for a long time outside the Anti-Terrorism Squad’s office, in Shivajinagar, they called me inside. “What happened?” I asked Jyoti, as soon as I met her. She was on her way to meet us, Jyoti said. As soon as she left the house, she noticed some suspicious people standing nearby who started following her vehicle. At the next signal, a female police officer got out of a police van, stopped her two-wheeler, and said, “You are under arrest.” Hearing this, all I could think was how dramatic it was!

Even though Jyoti had responded by email to everything the police asked, she was still arrested as if she was some notorious criminal or gangster. I smiled and told Jyoti, “Don’t stress too much. Take care of yourself in jail. Stay strong mentally and physically. Continue your studies. I’ll send all your counselling books. We’ll arrange money orders for you from time to time.” We could only talk briefly. Her belongings were handed over to me, and we smiled and hugged each other. I assured her that I would see her again soon and left. A female officer from the ATS was watching us with surprise. Her expression suggested that she was wondering why there was no fear on our faces.

After Jyoti’s arrest, the COVID pandemic began. Our sathis were no longer presented in court, so we could not meet them. Since then, all my meetings with Jyoti have taken place at the Mumbai sessions court. I’ve always been curious about what happens inside the jail and about their daily routines. But there’s no time for such discussions on court dates. Our primary concern is to know about their well-being, their needs, whether they received the money order, their health issues, news from the outside world, and updates about home. Inmates are usually very interested in knowing what’s happening outside. It gives them a sense of belonging. Considering that these people, until recently, were free as birds and are now confined to a room, their desire to know about the world outside is utterly natural.

Whether it is the BK-16 case or the old UAPA case against the Kabir Kala Manch, I had grown quite irritated with the entire system of courts, police, lawyers, and judges, having dealt with it since 2013. The primary reason is that when we travel to another city, it feels different from our own—for instance, the intense heat in Mumbai and how it leads to dehydration and exhaustion. For three or four years, I couldn’t understand why I felt irritated as soon as I arrived in Mumbai. But now I realise that with the change in environment, we need to adapt not only mentally but physically as well. So now, I pay attention to issues like dehydration whenever I go to meet my sathis on court dates. Besides the heat, Mumbai has a crowded and hectic atmosphere, which is also evident in the court. It’s always swarmed with the prisoners, their relatives, police, military, and lawyers. Amid all the commotion, a tea vendor serves tea and water to everyone in the court premises.

Nothing is ever certain about court dates. Will our imprisoned sathis be produced in court or not? If they are, how long will they be in court? How many will be brought? On 3 June this year, when I went to Mumbai from Pune, not all our sathis were brought in due to a shortage of guards because of the elections. So, nothing is definite. We always have to check with the lawyer. Sometimes we find out upon arrival that they won’t be brought in that day. Even if they are brought in, there is no guarantee of how long they will be in the court. Sometimes they may be there for the entire day, and sometimes they might be around for just 10 minutes or half an hour.

On the 3rd, almost all the cars and trains were delayed due to the election. When we got off the train and boarded a taxi, we received a message from the lawyer saying, “Jyoti has arrived at the court.” Five minutes later, another text followed: “You need to come as soon as possible because they are taking Jyoti away.” We wondered how it was possible that they could take her away in just ten minutes. These kinds of questions often run through our minds. That day, we somehow managed to get to the court, shook hands with her, and asked about her well-being. Then, within ten minutes, the police took her away. Despite many requests from us, the lawyers, and Jyoti herself, the police did not budge at all.

“We have come from Pune,” I said. “Just give us a few more minutes.” But they refused. So even after a five-hour journey to get there and another five-hour journey back, you can’t be sure of a meeting. We also have to take a whole day off for a court date, which includes the cost of travel and food. We have been through this so many times that we now understand how the system always dictates what we should and shouldn’t do. It’s tough to decide whether to feel happy about meeting our sathis or sad about meeting them for just ten minutes after a ten-hour journey.

Once, I asked Jyoti about her daily routine in jail. She told me that she reads books, exercises, is learning English, and also counsels other women. She helps them as much as possible with their legal processes. Last time, she asked me to find out about the organisations that help women rebuild their lives after completing their prison term. Jyoti’s activism continues even inside the jail, because there are people who need help both inside and outside.

Jyoti is now allowed to make video calls to her family, so we don’t usually talk about her parents or family anymore, since she can speak to them directly. Occasionally, I speak to Jyoti’s mother on the phone. She always asks me what wrong Jyoti committed, and when will she get bail. I know I have answered this question a hundred times before, but still, I explain everything to her each time. I try to help her understand, from her perspective, the concept of satta (power), desh (country), deshdroh (treason), the issues of jal-jungle-jameen (water-forest-land), and what it means to be an activist and an artist.

We are all political activists, so we mostly talk about politics, the outside environment, organisations, rallies, movements, and the struggles of other activists. Jyoti has applied for bail. There is a chance that she might get it. We discussed that if she gets bail, we’ll need two people and all their documents ready in time for her surety. I told her that I am continuously trying to find such people. I assured her that I am looking for the people who can help her lead a better life once she gets out and support her counselling centre as well. I told her that if there is a change in the government, there is a possibility that she and all the BK-16 might get bail.

We talked about all these things as we walked. The police were taking her away. A barricade ahead stopped us. From there, the police put Jyoti into a vehicle parked a short distance away and took her back to jail.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.