BK-16 Prison Diaries: Ramesh Gaichor on the Elgar prisoners’ defiance of the neo-Peshwai prison system

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork. (This piece has been translated into English by Vernon Gonsalves, read the original in Marathi here, and the Hindi translation by Prashant Rahi here.)

Jinhe naaz hai Hind par unko lao

Jinhe naaz hai Hind par woh kahaan hain?

(Bring those who are proud of this land

Where are they who are proud of this land?)

These lines of Sahir Ludhianvi, written shortly after the country gained independence, still strike a deep chord. But today, in what way will the neo-Peshwai government of this country receive these words, and what will it do to poets and song-writers like Sahir?

Perhaps it will put them behind towering impenetrable walls, erected over segregated acres of land, under the watchful eye of 24-hour security guards, armed with firearms, lathis, and belts. In this country, where things like the constitution, human rights, equality and humanity once held sway, these walls create a calculated and oppressive aura of awe around the khaki uniform that symbolises the police’s reign of terror. It is a site of state-sponsored trampling of basic rights; of inhuman treatment of humans; of crushing the self-respect of the innocent at every step; of depriving a person of the minimum requirements of a human existence; of forcing an animal existence on humans; and of repressive games designed to ensure that not a whisper of this unconstitutional, illegal, dictatorial system escapes beyond those gigantic walls.

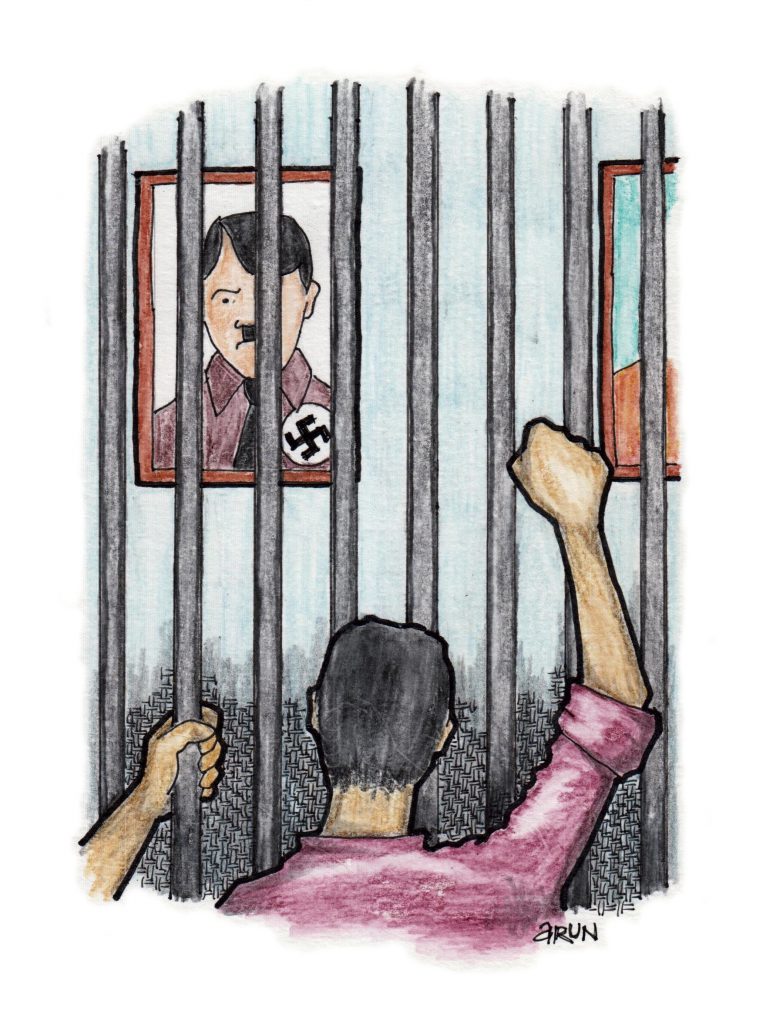

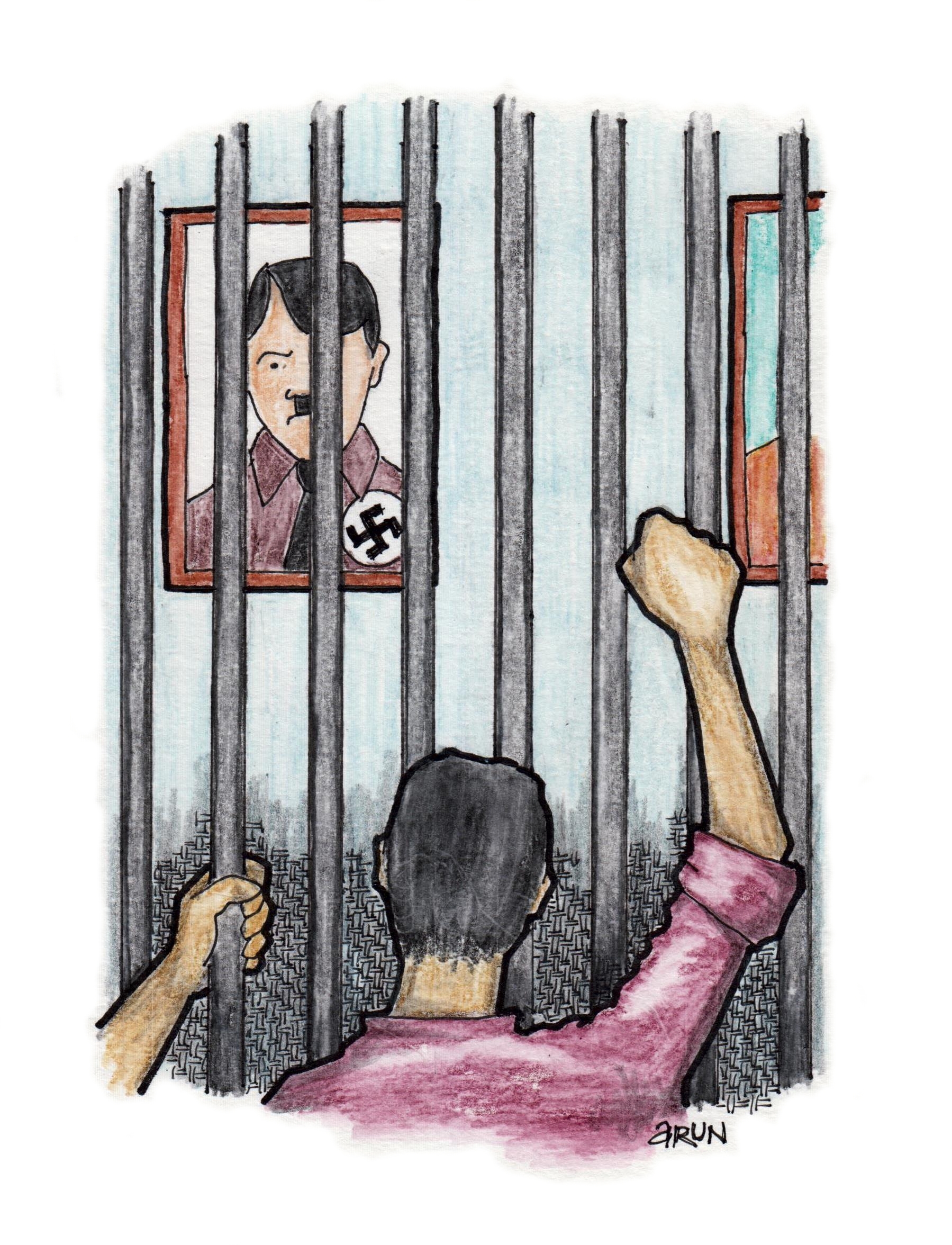

I am not speaking of Hitler’s fascist Germany, but of the prison where I have been lodged as an undertrial for the last four years. The prison takes great precautions to make sure that its true nature remains under wraps, hidden behind those lofty stone walls. Those who speak highly of the prison management are praised; those who tell the truth are punished, suppressed. In this way, the prison is a reflection of today’s neo-Peshwai system in the country—the system that brought us here because we refused to bow before it.

Sometime before the arrest that was made to happen, on 7 September 2020, I wrote the following lines:

Fascist Sattene malaa don paryay dile

Azaadi kivha turung

Mi turung nivadlay

Kaaran,

Bhik mahnun padraat padlelya Azaadipeksha

Majha man turungaat samadhanana jagu shakel

(The fascist state offered me two alternatives

Freedom or prison…

I chose prison

Because,

Rather than take the freedom dropped as alms

My heart would be able to live happier in jail)

These lines didn’t dawn on me during some serene, secluded, pleasant, electrifying thought moment. These lines are symbolic of a see-saw struggle. These lines came when facing up to the fake conspiracies and pressures of this country’s National Investigation Agency.

“Accept the story that the Maoists were behind the organizing of the Elgar Parishad; and it is us who’ll tell you how, and who all were in it, you have just to sign. That’s all! We will not arrest you, and if you don’t do this, then take it for granted that you’ve gone to jail for a long spell. Don’t decide in a hurry. Go home. Think calmly. Discuss with your folks at home, those close to you, and take your time and decide. Go home. Come tomorrow.”

These were the words of a senior NIA officer. These words were not in any loud voice. They were not grabbing our collars and yelling. They weren’t being abusive and insulting. It was not like the pattern of normal police remands. They were sophisticated words in a peaceful and gentle tone, explaining it in the tone of someone telling you something that is in your interest, to your advantage.

These words took us—Sagar and me—to the precipice. This was not our first experience of a police investigation. During our earlier prison spell, we had come to know the remand and the judicial processes quite well. So we knew what they were asking for, and under what section, and what would happen if we did not give. We knew all this too well.

But there was no need for any discussion or deliberations with anyone. Perhaps it was us who did not leave any space for such discussions. We decided and left the next day, with a sack over our shoulders, prepared to go to jail—somewhat laughing, somewhat crying, and a mighty storm whirling within. I bid farewell to the activists of our cultural group and other activists of the movement. I spoke a few words over the phone with those at home.

My life-partner, Harshali, and I understood the intensity of the storm. The whole idea of political commitment is deeply imbibed within her, yet she could not hold back her tears streaming down. With this teary farewell, and cherishing her words—“I am proud of your decision to face up to this repression”—I went in and got arrested.

Sagar and I spent the ten days of police remand in a windowless, iron-barred room, reading books and speaking with each other. The light was switched on 24 hours. It felt as if it was always day—a sense of it never becoming night, with a 24-hour watch at the door. I got good, quiet time to read Balchandra Nemade’s novel Hindu and collections of stories by Balaji Sutar, Jayant Pawar and Neerja.

There was no real investigation. They were not getting what they wanted from us, and so, without any other inquiry, they used the old false case in which we had already obtained bail to send us to prison as accused in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case. In court, the advocates Nihalsingh Rathod and Barun Kumar argued well, but we were sent to judicial custody. And once again, we landed in the same Taloja Central Jail from where we had been released on bail in 2017.

This is Sagar and my second spell in prison, after our first stint from 2013 to 2017, and now, from 2020 to 2024, almost four years and counting. Such a long period in prison, under the deceptive, hypothetical, fabricated accusations of “urban naxal,” and under the provisions of the Hitlerite law called UAPA.

Why? For what? The answers to these questions lie in the life-struggles of all those known and unknown revolutionaries whose ideals brought us to devote ourselves to the fight for equality. It was because we were continuously raising our voices against the inegalitarian social system that we were arrested in 2013. What was the medium through which we raised our voices? Songs, poems, street-plays, ballads. The Brahminical-Capitalist rulers feel that the creative expressions of art and culture are guns and bombs.

Then we remember the revolutionary litterateurs who have risen from this soil like Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh, who says, “Abh abhivyakti ke saare khatre uthaane hi honge, todne honge hi math aur gadh sab!” (Now all those threats to expression will have to confronted, all monasteries and fortresses will have to be broken!)

And what about the people’s balladeer, Wamandada Kardak, who bluntly questioned the system: “Sangaa amhaala Birla, Bata, Tata, kutha haay ho? An sangaa dhanaacha saatha na amchaa vaata kutha haay ho?” (Tell us where are Birla, Bata, Tata, oh? And tell where is our share of that hoard of wealth oh?)

If we, through his ballads, cannot inculcate his life into ourselves, then they are mere entertainment. Art is not just for art’s sake, it is for making life beautiful, and life can only become beautiful when there is equality in society; there can only be equality when this inegalitarian system is no more, and then struggle becomes inevitable for this inegalitarian system to be no more. This has been going on from time immemorial and we have been working to this day following this principle.

This is why, in September 2017, when the former Supreme Court judge, the late respected Justice PB Sawant sir, and the former High Court judge, Justice BG Kolse Patil sir, gave a call to all Ambedkarite, democratic-constitutionalist organisations to come together against today’s neo-Peshwai system, we joined as our cultural group.

To this day, I remember the presidential speech of Justice PB Sawant at the preparatory meeting for the Elgar Parishad at Pune’s Sane Guruji Smarak, in October 2017: “Bhima Koregaon is our identity; that is why we have to hold it high and fight against this Manuvadi system.” All the organisations gathered together under his convenorship and guidance, and the people as a whole, gave shape to the Elgar Parishad. Elgar Parishad became the voice of the joint battle of the people against the neo-Peshwai.

The songs, poems, ballads, street-plays, speeches were a clear rebellion against the RSS- affiliated Bharatiya Janata Party government. It was a rebellion, not a “conspiracy,” as they have sought to make out in their case against us. A conspiracy is when the planning is done in secret, without openly saying anything—like the attacks on Dalits and Bahujans at Bhima Koregaon on 1 January 2018, organised by Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote. Every aim and action-programme of the Elgar Parishad was announced openly from the start. Right from naming the BJP as a neo-Peshwai government, to taking a pledge never to vote for the RSS-affiliated party—all was done keeping democracy and the Constitution as the standard, in which there was nothing devious. The slogan of the Elgar Parishad was “Save the Constitution, Save Democracy, Save the Country!” The Elgar Parishad was conducted peacefully. Then how did this case come about?

The Elgar Parisha-Bhima Koregaon case: The biggest government conspiracy in the world

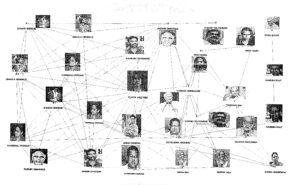

I, we, and the people of our country have been saying this, but it is not just us—it was even said three years ago by the world’s best forensic analysis company, Arsenal Consultancy. Why was the Elgar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case created? How did the police plant evidence in a strategic manner? How was a big conspiracy hatched to arrest activists from different states across the country? How was the attack at Bhima Koregaon on 1 January 2018 orchestrated, and how was it portrayed as a clash between two groups? What impact did this have on the socio-political atmosphere throughout the state? How were the perpetrators of the assault, Bhide and Ekbote, saved by accusing the Elgar Parishad?

Over the last six years, through the writings of professors, writers, thinkers, artists, and activists, the answers to all these questions have been placed concretely before the people. The BJP government has continuously made attempts, by concealing the truth and using its entire propaganda machinery, to propagate itself; but yet they have not been able to stop people from exposing the true picture of this conspiracy before the masses.

Many eminent personalities from the country and various parts had conducted a campaign of “MeToo Urban Naxal” to protest the arrest of the BK-16. The BJP in power spread falsehoods and tried to polarise the public, particularly the Ambedkarite masses, but the people defeated this game of polarisation. The fight over the case continues at all levels.

In fact, while the case has been sub-judice, seven of the BK-16 prisoners are out on bail. Father Stan Swamy was martyred during imprisonment. We, the remaining eight, are still in prison. The possibility of bail or of acquittal upon completion of the case is not the least in sight, it does not even come in our dreams. Everything is scarily uncertain. This uncertainty is like some respiratory disease enveloping every breath.

But what really is this earthquake that has entered our lives in the name of imprisonment? What are its reasons? The mind has grown alert enough in the fellowship of the movement to understand this clearly. The movement has taught us to analyse the causes behind this political repression brought on by the system.

Elgar-waale machaandis (The Elgar protesters)

I can unequivocally say that my experience of eight years of prison life—the previous four and the present four—is that of systemic violence. This institution projects a motto and aim of “reform and rehabilitation,” yet does not do the slightest work in this direction. In fact, there is no one here who has the slightest understanding about its basic objective. Instead, you see a prison administration that is highly insensitive about humaneness. Here, everyone who has been appointed is visibly involved in everything but what should be their fundamental duties and responsibilities.

At every step one encounters a rotten system steeped in corruption, and there begins our struggle against this inhuman system that is sometimes sharp, sometimes gentle, sometimes extreme, and sometimes creative. We have largely been recognized here as “Elgar-waale”—the Elgar ones. To some extent, we have been able to put pressure on the system, and to some extent, this system has been able to put pressure on us. The struggle against the prison is a daily occurrence here. Every day, the system creates new obstacles, new rules, new problems, and stories of these conflicts within jail are always told, from some corner or the other.

Thus, this ongoing battle is composed of several varied struggles. This includes the struggle of Sudhir, Sagar and Gautam against the illegal feudal custom of removing footwear when standing before the prison superintendent or other senior officers; the struggle in the video conferencing court against the superintendent’s arbitrary, revengeful, wrongful use of his post to arbitrarily decide against sending us to court despite the judicial order for production in court; and the court complaint by Surendra Gadling against the superintendent and prison medical officer against their decision to stop life-saving drugs at the gate for two or three months, ultimately making them disappear. It includes the complaint application by Surendra, Sagar and me that “the death of Father Stan Swamy, a co-accused in this case is not natural, but an institutional murder.”

There were never any alternatives but to struggle. Surendra, Sudhir, Sagar and me launched a struggle in the anda cell when Vernon Gonsalves was not sent to the hospital outside despite being severely ill with dengue; and Sudhir, Arun and me led a struggle against the superintendent for unlawfully holding back our outgoing letters and also sending them to NIA and ANO. Sagar had to go on a hunger strike for adequate water for the prisoners, against the lack of any facilities for relatives of prisoners who came for prison visits, to start the system of phone calls, and against the absence of necessary medical treatment.

The prison system displayed petty authoritarianism and corruption in all matters. Mosquito nets were forcibly taken away. In response, I filed a court complaint against the superintendent and the medical superintendent, and Sagar filed a police complaint of theft at the local police station, against the narrow and dictatorial practice of the jail authorities. Rona, Mahesh and Hany led an important struggle against the increasing rates for the canteen’s special bhaji. One had to struggle against corrupt practices such as giving 600-gram broth and 400-gram chicken, which one has to buy from the prisoners’ own money, for the chicken supplied once a week.

When the truth is buried and corruption is rampant, it becomes necessary to expose it using the Right to Information Act. These days, the struggle against corrupt officers of the canteen is ongoing. These struggles are not new for us Elgar prisoners. They have been going on since we came into prison and will go in the future too.

These things are called “machaand” in prison. We Elgar prisoners have led many a machaand—it is why we were branded as “machaandis” and kept in the Anda Cell. The Anda Cell is now being demolished, so we have been sent back into the General Circle. This Anda Cell, which was built just twenty years ago from government expenditure, has reached a stage of collapse already. Poor construction, adulterated building materials and corruption in government funds are among the several reasons for this. We are trying to expose this scam.

Outside prison, the people are fighting hard against the neo-Peshwai system and the energy from these struggles is the basis on which we, the Elgar prisoners here in prison, are trying to live by continuing to fight against the system here. Though this struggle we are waging inside may not be that tough, we have been successful enough to force the prison administration to give in to our demands regarding our rights, justice and self-respect.

The Prison Complex: Systemic violence under the guise of reformation

Why has this system created prisons? One does not realize this clearly unless one goes into prison. Some so-called social workers and intellectuals consider prisons to be universities; but I consider them only torture chambers and nothing else. Even if one gets quiet time for reading and writing, there is never any positive space or mental state for reading and writing.

The prison’s nature and structure are designed to emasculate every type of activist within you. That this emasculation does not take place in reality could be a question of research. But it is true that the prison always influences the activist in you and has a negative impact on you.

The prison sows fear. The prison troubles you. In the name of self-examination, of life-analysis, the prison throws you on the back-foot. The prison tells you to cut down the revolutionary participation of your earlier days—to shift it, to change it.

The prison isolates you a great deal from everything that you value in life; which is yours by right, which you like and which is close to your thinking. The prison gives you a sharp realisation of how great a sorrow it is to have your liberty snatched away from you. Every form of liberty is denied to you here.

The Jail Manual, the directives of the Human Rights Act, and the judgments of the Supreme Court and high courts are all thrown to the winds by the jail administration. The jail continues to do whatever pleases its corrupt and dictatorial mindset. The arbitrariness of the prison is extremely annoying. It seems as if it is the routine of the prison system to keep the prisoner in a permanent state of tension.

The inhuman behavior begins as soon as one steps into prison, with the assumption that every person who has entered the prison is a criminal, and that one who utters a syllable against this inhuman behavior has to bear strict punishment and insults. All of us went through this inhuman behavior. We have, through our struggle, from the very beginning, compelled the system to behave with us humanely and in accordance with law. We have proven to be a great nuisance to the system, leading the administration to harbour great animus towards us, but we have also earned a position of respect among the hearts of many of the prisoners.

This is because the movement for equality has sown the concepts of “self and society” and “individualism and collectivism.” It is therefore necessary to underline the import of the collectiveness, of the unity and of the preparedness of these struggles of the Elgar prisoners. This, I would say, is because the reality here is more intense, more serious, more extreme and more challenging.

People here die due to lack of treatment and the system here does not even experience a scratch. Many here rot for days on end because court hearings do not take place, and due to lack of proper legal aid. The system here does not in the least care about human lives rotting and dying away. Everything is suppressed in a planned manner. It is repressed. There is a massive administrative net of a commonality of interests from the bottom to the top, from inside to outside that is ever ready to support the prison system. Many things are managed, many things are settled.

The screen of the impenetrable walls comes in handy to cover up the injustices and illegalities. This system does not allow any organised resistance to take shape against the injustices here. The prison is ever alert about this. The 24-hour watch, the net of CCTV cameras, the unofficial network of informers is all used very efficiently. Any possibility of resistance is halted. The prison immediately becomes very ferocious against any voice of resistance rising in opposition.

Punishment is meted out arbitrarily for this. The prison imposes punishments such as naalbandhi—the practice of directing prisoners to wedge their feet between the iron bars of a gate or barrack, and then beating them on their soles with batons; beating with a thick canvas belt; solitary confinement for an indefinite period; stopping of visits, letter correspondence and court dates; mental torture; externment from a circle; changing of circle; confiscation of books; and so on.

Here, hurting the ego of the jail is also a major crime. The ego of the prison administration is of a police-like nature—the ego of the khaki uniform, the ego of being on a police officer’s post. With this ego, the prison uses whatever means it can to force every prisoner to succumb and survive by prostrating himself. Here, you have to obey what the officer says, do as the officer orders. This is the way of the police. No asking for any clarifications: Why? For what? Such questions must not be asked. And never say, “I will not accept this order.” Any such action hurts the ego of prison administration; and if the ego of the prison is hurt, they will become all the more inhuman with you.

You become a target of the prison and the prison uses its power to keep an eye on you, in order to suppress you. It becomes active and alert, to give you trouble and mental tension at every stage. For example, when you return to jail from court and your body search is done at the Lal Gate—the main entry gate—you are made to remove all your clothes and stand in your underwear, and the guard there pulls open your underwear to see if there is anything there. He starts examining, he gropes your private parts with his hands, and sometimes he puts his finger into your anus and feels around thoroughly. You have to endure all this. The CCTV cameras at the gate, the female staff at the gate, the bright lights at the gate, meaning everything is totally open and in the midst of all this, you have to stand naked—even if it does not accord with any rules, yet you have to follow it. For if you do not, the ego of the prison is hurt.

The prison very casually perpetrates this assault on one’s self-esteem and self-respect, and easily digests such unlawful activity. This act of stripping off a prisoner’s clothes with a casual “how did it go” is actually a salve to the prison’s ego. These forceful acts to assuage the prison’s ego are practiced elsewhere too—such as squatting half-naked in the checking hall in front of the superintendent; waiting without footwear in front of a senior officer or outside his office; witnessing all your belongings being thrown around here and there, upside down, during barrack searches; not saying a word about the falling standards of the daily tea and breakfast; eating without any complaint the half cooked chapattis and tasteless bhaji and dal; keeping quiet regarding the adulteration of the milk; tolerating the corrupt practices going on in the prison canteen being run on a no-profit, no-loss basis. All in all, tolerating all the corrupt and illegal practices and treatment of the prison is caressing the ego of the prison. It is a serious crime to hurt the ego of the prison. We have committed this serious crime several times, and have been targeted by the prison for it, vengefully sent here and there.

Imprisonment carries with it another painful hideousness—separation. The reality of separation, of an existence of enduring the torture of staying apart from one’s life-partner, wife, lover, pierces like a thorn at every step inside prison. Only twenty minutes of a countdown-like meeting. What exactly to say? And what to listen to? How much should one see? How much to store in the mind’s eye? It all flies past in a flurry. The twenty minutes go by in the chaos of somehow stitching together the points about court issues, other necessities, and conveying messages of various others. The prison employees and officers at the meetings sharply cut off your phone. The dialogue building up in your heart is broken off in a moment, and you are left speechless and helpless, looking through the glass before you, at the face of your loved one.

There is only the glass of a window between the two, but it becomes impossible to cross that tiny distance and even give a hug to your dearest. You silently say bye with your eyes and hands, and leaves, and then remembers that in all that hurry, you forgot to even ask “how are you?”

A calmness takes over the soul. The heart eats itself out. A great anger of the self on the self surges and takes over. Light tears spill out. Separation becomes dreadful, like the pricks of thousands of thorns. It is the same for everyone. The burden of separation has to be borne by the accused facing trial—the undertrial prisoner who, despite being innocent, has to tolerate this—and also by the life-partner, who despite not being an accused, despite not having any offence, has to live the torment of separation. The prison, the court, no machinery spares a humane thought about this.

Letters are read line by line by the officers here, so there is a watch on writing too. The suffocation and restlessness of the mind of the prisoner is not seen in the open, but the scale of this restlessness is immense. But this restlessness is like some incurable disease that keeps on growing its disfiguring presence within the soul. A person laughing from the outside is internally troubled, sad and drifting at a loose end. He does not get a space, a refuge that can bring him peace of mind. Nights are desolate and agitated, days are blank and empty, somewhat like Gulzar’s song: “Din khaali khaali bartan hain, raat hai jaisa andhaa kua”—Days pass like empty vessels, nights are like dark wells.

Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi (That dawn will eventually break)

So, all in all, there is no reason to have any misunderstanding or lack of clarity regarding this repression. Who are the enemies? And who are the friends? This has been brought forth clearly by these times. It was not that this was not so earlier; but this period, particularly prison, has given a good space for thought and that thought has given a good opportunity for making one’s own political and emotional analysis. My words may suggest that everything is very negative. Indeed, the situation is filled with negativity, but the torch of positivity and hope in one’s mind also remains burning in these dark times. The energy for keeping that flame alive has been provided by the movement.

Despite this suffocating, enclosed, inhuman atmosphere, I have been able to creatively preserve myself as an artist activist. I have received very valuable assistance from the family of the movement outside prison and of the family of Elgar prisoners within it. I have been able to write about this prison, to write poems about this phase of repression, to read a lot, and to discuss things calmly with experienced senior persons of the movement.

I have learnt many new things from such discussions—concepts became much clearer, I got the answers to unanswered questions, and I now understand the past of the egalitarian movement closely and somewhat deeply. I have been able to grasp every feeling on my mind peacefully and calmly, in a very beneficial manner, and to delve deeper into understanding the concept of living together.

By this I mean to say that I have not been able to do much and yet I have, even in this captivity, been able to do quite a bit. Prison injures a lot of your things. It keeps a constant watch on your every expression. Yet our expression could pierce past these walls and reach the people outside. It was a source of great inspiration to us that our words, our poems, our calls to struggle could cross these massive stone walls and reach the people, and that the people paid heed to and embraced our expression. That the people did not allow us to be cut off from them and that our links with the people remain strong till today is something that gives us a strong basis to persevere.

Though this repression has isolated us from the broad people’s movement and kept us alone in jail, I do not look at this repression at a personal level at all. I look at this repression as a part of the wide-ranging repression being carried out in the country by this fascist state. Thousands of people’s agitations have taken place since 2014 against the neo-Peshwai in central cities like Delhi, Mumbai and in various corners of the country.

The people throughout the country have raised the call for struggles against hundreds of injustices and repressive acts, against displacement, against anti-people laws, against illegal encounters and torture, against the commercialisation and Brahmanisation of education, against the anti-constitutional cultural politics of the Manuvaadi forces, and against the government-backed conspiracies of the central investigative agencies. Every such call has been met by state repression—in these circumstances, one clearly feels that the repression meted out to the Elgar prisoners is but a part of this broader repression.

I am not despondent because my estimations and my understanding of the movement carry the mature intent of the history of many thousand years of revolutionary struggles. This understanding reminds me continuously, over and over, of the revolutionary stories of people’s struggles fought firmly against repression, and of the ideals of those leading them.

This historical fighting aim does not allow the agitating, struggling artist-activist in me to die. It helps me hold out against the suffocating besieged prison atmosphere. And I am proud that this is the mental state of all of us BK-16 Elgar prisoners.

Sometime in the Anda Cell of the Taloja Central Jail, the electricity would go out suddenly at seven or eight at night, and the already uncertain atmosphere would become frightfully silent. In such quiet surroundings, one feels terribly alone. In that deep darkness, only the iron bars can be seen. Normally nothing can be done on such frightful nights. A momentary utopia struggles to achieve domination over existence. With flitting eyes, one starts fumbling with thoughts that start helplessly churning.

The prison starts dominating in a dreadful manner. In such an oppressive setting of solitude, my inner mind goes blank and I become forced to sit with my head tucked in. I would start sinking into my own cocoon, but just then, the high-pitched tone of Sudhir would tear apart that frightful darkness and reach out, carrying a beacon of light to me.

The song would be of Sahir: “Sar jhukane se kuch nahin hota hai, Sar uthao tho koi baat banein”—(Nothing has comes from bowing your head; Something can come from holding your head high). The song would lift the spirits of the whole Anda Cell listening to him.

Then, Sagar would start: “Ye dastoor ko, subah be-noor ko, mai nahin maanta, main nahin jaanta”—(Such a norm, this lightless morn; I do not respect, I do not accept). Then Gadling sir would begin his recitation of Kabir’s couplet: “Nadiya naav mein doob jaaye re”—(The river is drowning in the boat). Gautam would then elevate the mood with “Woh subah kabhi to aayegi”—(That dawn will eventually break). Then I would sing the song, “Mera rang de basanti chola”—(Give my robe the colour of spring).

Song would join song and person would link up with person. The feeling of loneliness would be hurled far away; because song, with its sublime scent of the collective spirit would pervade. For those in the Anda Cell hearing a song for the first time, it would carry something new, for those who had heard it before, the old would be rediscovered anew. The dark empty night of the Anda Cell would, with these meaningful songs, grow intense with intent. And on such a night, some lines would blossom from the heart…

Mashaali vizhlya nahit ajunhi

Damanamagun daman zari

Dhag uraauraat ajunhi

Turung punha punha zari

(The torches have not yet dimmed

though repression follows repression

The flame is alive in every part

though imprisonment follows imprisonment)

Related Posts

BK-16 Prison Diaries: Ramesh Gaichor on the Elgar prisoners’ defiance of the neo-Peshwai prison system

Jinhe naaz hai Hind par unko lao

Jinhe naaz hai Hind par woh kahaan hain?

(Bring those who are proud of this land

Where are they who are proud of this land?)

These lines of Sahir Ludhianvi, written shortly after the country gained independence, still strike a deep chord. But today, in what way will the neo-Peshwai government of this country receive these words, and what will it do to poets and song-writers like Sahir?

Perhaps it will put them behind towering impenetrable walls, erected over segregated acres of land, under the watchful eye of 24-hour security guards, armed with firearms, lathis, and belts. In this country, where things like the constitution, human rights, equality and humanity once held sway, these walls create a calculated and oppressive aura of awe around the khaki uniform that symbolises the police’s reign of terror. It is a site of state-sponsored trampling of basic rights; of inhuman treatment of humans; of crushing the self-respect of the innocent at every step; of depriving a person of the minimum requirements of a human existence; of forcing an animal existence on humans; and of repressive games designed to ensure that not a whisper of this unconstitutional, illegal, dictatorial system escapes beyond those gigantic walls.

I am not speaking of Hitler’s fascist Germany, but of the prison where I have been lodged as an undertrial for the last four years. The prison takes great precautions to make sure that its true nature remains under wraps, hidden behind those lofty stone walls. Those who speak highly of the prison management are praised; those who tell the truth are punished, suppressed. In this way, the prison is a reflection of today’s neo-Peshwai system in the country—the system that brought us here because we refused to bow before it.

Sometime before the arrest that was made to happen, on 7 September 2020, I wrote the following lines:

Fascist Sattene malaa don paryay dile

Azaadi kivha turung

Mi turung nivadlay

Kaaran,

Bhik mahnun padraat padlelya Azaadipeksha

Majha man turungaat samadhanana jagu shakel

(The fascist state offered me two alternatives

Freedom or prison…

I chose prison

Because,

Rather than take the freedom dropped as alms

My heart would be able to live happier in jail)

These lines didn’t dawn on me during some serene, secluded, pleasant, electrifying thought moment. These lines are symbolic of a see-saw struggle. These lines came when facing up to the fake conspiracies and pressures of this country’s National Investigation Agency.

“Accept the story that the Maoists were behind the organizing of the Elgar Parishad; and it is us who’ll tell you how, and who all were in it, you have just to sign. That’s all! We will not arrest you, and if you don’t do this, then take it for granted that you’ve gone to jail for a long spell. Don’t decide in a hurry. Go home. Think calmly. Discuss with your folks at home, those close to you, and take your time and decide. Go home. Come tomorrow.”

These were the words of a senior NIA officer. These words were not in any loud voice. They were not grabbing our collars and yelling. They weren’t being abusive and insulting. It was not like the pattern of normal police remands. They were sophisticated words in a peaceful and gentle tone, explaining it in the tone of someone telling you something that is in your interest, to your advantage.

These words took us—Sagar and me—to the precipice. This was not our first experience of a police investigation. During our earlier prison spell, we had come to know the remand and the judicial processes quite well. So we knew what they were asking for, and under what section, and what would happen if we did not give. We knew all this too well.

But there was no need for any discussion or deliberations with anyone. Perhaps it was us who did not leave any space for such discussions. We decided and left the next day, with a sack over our shoulders, prepared to go to jail—somewhat laughing, somewhat crying, and a mighty storm whirling within. I bid farewell to the activists of our cultural group and other activists of the movement. I spoke a few words over the phone with those at home.

My life-partner, Harshali, and I understood the intensity of the storm. The whole idea of political commitment is deeply imbibed within her, yet she could not hold back her tears streaming down. With this teary farewell, and cherishing her words—“I am proud of your decision to face up to this repression”—I went in and got arrested.

Sagar and I spent the ten days of police remand in a windowless, iron-barred room, reading books and speaking with each other. The light was switched on 24 hours. It felt as if it was always day—a sense of it never becoming night, with a 24-hour watch at the door. I got good, quiet time to read Balchandra Nemade’s novel Hindu and collections of stories by Balaji Sutar, Jayant Pawar and Neerja.

There was no real investigation. They were not getting what they wanted from us, and so, without any other inquiry, they used the old false case in which we had already obtained bail to send us to prison as accused in the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case. In court, the advocates Nihalsingh Rathod and Barun Kumar argued well, but we were sent to judicial custody. And once again, we landed in the same Taloja Central Jail from where we had been released on bail in 2017.

This is Sagar and my second spell in prison, after our first stint from 2013 to 2017, and now, from 2020 to 2024, almost four years and counting. Such a long period in prison, under the deceptive, hypothetical, fabricated accusations of “urban naxal,” and under the provisions of the Hitlerite law called UAPA.

Why? For what? The answers to these questions lie in the life-struggles of all those known and unknown revolutionaries whose ideals brought us to devote ourselves to the fight for equality. It was because we were continuously raising our voices against the inegalitarian social system that we were arrested in 2013. What was the medium through which we raised our voices? Songs, poems, street-plays, ballads. The Brahminical-Capitalist rulers feel that the creative expressions of art and culture are guns and bombs.

Then we remember the revolutionary litterateurs who have risen from this soil like Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh, who says, “Abh abhivyakti ke saare khatre uthaane hi honge, todne honge hi math aur gadh sab!” (Now all those threats to expression will have to confronted, all monasteries and fortresses will have to be broken!)

And what about the people’s balladeer, Wamandada Kardak, who bluntly questioned the system: “Sangaa amhaala Birla, Bata, Tata, kutha haay ho? An sangaa dhanaacha saatha na amchaa vaata kutha haay ho?” (Tell us where are Birla, Bata, Tata, oh? And tell where is our share of that hoard of wealth oh?)

If we, through his ballads, cannot inculcate his life into ourselves, then they are mere entertainment. Art is not just for art’s sake, it is for making life beautiful, and life can only become beautiful when there is equality in society; there can only be equality when this inegalitarian system is no more, and then struggle becomes inevitable for this inegalitarian system to be no more. This has been going on from time immemorial and we have been working to this day following this principle.

This is why, in September 2017, when the former Supreme Court judge, the late respected Justice PB Sawant sir, and the former High Court judge, Justice BG Kolse Patil sir, gave a call to all Ambedkarite, democratic-constitutionalist organisations to come together against today’s neo-Peshwai system, we joined as our cultural group.

To this day, I remember the presidential speech of Justice PB Sawant at the preparatory meeting for the Elgar Parishad at Pune’s Sane Guruji Smarak, in October 2017: “Bhima Koregaon is our identity; that is why we have to hold it high and fight against this Manuvadi system.” All the organisations gathered together under his convenorship and guidance, and the people as a whole, gave shape to the Elgar Parishad. Elgar Parishad became the voice of the joint battle of the people against the neo-Peshwai.

The songs, poems, ballads, street-plays, speeches were a clear rebellion against the RSS- affiliated Bharatiya Janata Party government. It was a rebellion, not a “conspiracy,” as they have sought to make out in their case against us. A conspiracy is when the planning is done in secret, without openly saying anything—like the attacks on Dalits and Bahujans at Bhima Koregaon on 1 January 2018, organised by Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote. Every aim and action-programme of the Elgar Parishad was announced openly from the start. Right from naming the BJP as a neo-Peshwai government, to taking a pledge never to vote for the RSS-affiliated party—all was done keeping democracy and the Constitution as the standard, in which there was nothing devious. The slogan of the Elgar Parishad was “Save the Constitution, Save Democracy, Save the Country!” The Elgar Parishad was conducted peacefully. Then how did this case come about?

The Elgar Parisha-Bhima Koregaon case: The biggest government conspiracy in the world

I, we, and the people of our country have been saying this, but it is not just us—it was even said three years ago by the world’s best forensic analysis company, Arsenal Consultancy. Why was the Elgar Parishad-Bhima Koregaon case created? How did the police plant evidence in a strategic manner? How was a big conspiracy hatched to arrest activists from different states across the country? How was the attack at Bhima Koregaon on 1 January 2018 orchestrated, and how was it portrayed as a clash between two groups? What impact did this have on the socio-political atmosphere throughout the state? How were the perpetrators of the assault, Bhide and Ekbote, saved by accusing the Elgar Parishad?

Over the last six years, through the writings of professors, writers, thinkers, artists, and activists, the answers to all these questions have been placed concretely before the people. The BJP government has continuously made attempts, by concealing the truth and using its entire propaganda machinery, to propagate itself; but yet they have not been able to stop people from exposing the true picture of this conspiracy before the masses.

Many eminent personalities from the country and various parts had conducted a campaign of “MeToo Urban Naxal” to protest the arrest of the BK-16. The BJP in power spread falsehoods and tried to polarise the public, particularly the Ambedkarite masses, but the people defeated this game of polarisation. The fight over the case continues at all levels.

In fact, while the case has been sub-judice, seven of the BK-16 prisoners are out on bail. Father Stan Swamy was martyred during imprisonment. We, the remaining eight, are still in prison. The possibility of bail or of acquittal upon completion of the case is not the least in sight, it does not even come in our dreams. Everything is scarily uncertain. This uncertainty is like some respiratory disease enveloping every breath.

But what really is this earthquake that has entered our lives in the name of imprisonment? What are its reasons? The mind has grown alert enough in the fellowship of the movement to understand this clearly. The movement has taught us to analyse the causes behind this political repression brought on by the system.

Elgar-waale machaandis (The Elgar protesters)

I can unequivocally say that my experience of eight years of prison life—the previous four and the present four—is that of systemic violence. This institution projects a motto and aim of “reform and rehabilitation,” yet does not do the slightest work in this direction. In fact, there is no one here who has the slightest understanding about its basic objective. Instead, you see a prison administration that is highly insensitive about humaneness. Here, everyone who has been appointed is visibly involved in everything but what should be their fundamental duties and responsibilities.

At every step one encounters a rotten system steeped in corruption, and there begins our struggle against this inhuman system that is sometimes sharp, sometimes gentle, sometimes extreme, and sometimes creative. We have largely been recognized here as “Elgar-waale”—the Elgar ones. To some extent, we have been able to put pressure on the system, and to some extent, this system has been able to put pressure on us. The struggle against the prison is a daily occurrence here. Every day, the system creates new obstacles, new rules, new problems, and stories of these conflicts within jail are always told, from some corner or the other.

Thus, this ongoing battle is composed of several varied struggles. This includes the struggle of Sudhir, Sagar and Gautam against the illegal feudal custom of removing footwear when standing before the prison superintendent or other senior officers; the struggle in the video conferencing court against the superintendent’s arbitrary, revengeful, wrongful use of his post to arbitrarily decide against sending us to court despite the judicial order for production in court; and the court complaint by Surendra Gadling against the superintendent and prison medical officer against their decision to stop life-saving drugs at the gate for two or three months, ultimately making them disappear. It includes the complaint application by Surendra, Sagar and me that “the death of Father Stan Swamy, a co-accused in this case is not natural, but an institutional murder.”

There were never any alternatives but to struggle. Surendra, Sudhir, Sagar and me launched a struggle in the anda cell when Vernon Gonsalves was not sent to the hospital outside despite being severely ill with dengue; and Sudhir, Arun and me led a struggle against the superintendent for unlawfully holding back our outgoing letters and also sending them to NIA and ANO. Sagar had to go on a hunger strike for adequate water for the prisoners, against the lack of any facilities for relatives of prisoners who came for prison visits, to start the system of phone calls, and against the absence of necessary medical treatment.

The prison system displayed petty authoritarianism and corruption in all matters. Mosquito nets were forcibly taken away. In response, I filed a court complaint against the superintendent and the medical superintendent, and Sagar filed a police complaint of theft at the local police station, against the narrow and dictatorial practice of the jail authorities. Rona, Mahesh and Hany led an important struggle against the increasing rates for the canteen’s special bhaji. One had to struggle against corrupt practices such as giving 600-gram broth and 400-gram chicken, which one has to buy from the prisoners’ own money, for the chicken supplied once a week.

When the truth is buried and corruption is rampant, it becomes necessary to expose it using the Right to Information Act. These days, the struggle against corrupt officers of the canteen is ongoing. These struggles are not new for us Elgar prisoners. They have been going on since we came into prison and will go in the future too.

These things are called “machaand” in prison. We Elgar prisoners have led many a machaand—it is why we were branded as “machaandis” and kept in the Anda Cell. The Anda Cell is now being demolished, so we have been sent back into the General Circle. This Anda Cell, which was built just twenty years ago from government expenditure, has reached a stage of collapse already. Poor construction, adulterated building materials and corruption in government funds are among the several reasons for this. We are trying to expose this scam.

Outside prison, the people are fighting hard against the neo-Peshwai system and the energy from these struggles is the basis on which we, the Elgar prisoners here in prison, are trying to live by continuing to fight against the system here. Though this struggle we are waging inside may not be that tough, we have been successful enough to force the prison administration to give in to our demands regarding our rights, justice and self-respect.

The Prison Complex: Systemic violence under the guise of reformation

Why has this system created prisons? One does not realize this clearly unless one goes into prison. Some so-called social workers and intellectuals consider prisons to be universities; but I consider them only torture chambers and nothing else. Even if one gets quiet time for reading and writing, there is never any positive space or mental state for reading and writing.

The prison’s nature and structure are designed to emasculate every type of activist within you. That this emasculation does not take place in reality could be a question of research. But it is true that the prison always influences the activist in you and has a negative impact on you.

The prison sows fear. The prison troubles you. In the name of self-examination, of life-analysis, the prison throws you on the back-foot. The prison tells you to cut down the revolutionary participation of your earlier days—to shift it, to change it.

The prison isolates you a great deal from everything that you value in life; which is yours by right, which you like and which is close to your thinking. The prison gives you a sharp realisation of how great a sorrow it is to have your liberty snatched away from you. Every form of liberty is denied to you here.

The Jail Manual, the directives of the Human Rights Act, and the judgments of the Supreme Court and high courts are all thrown to the winds by the jail administration. The jail continues to do whatever pleases its corrupt and dictatorial mindset. The arbitrariness of the prison is extremely annoying. It seems as if it is the routine of the prison system to keep the prisoner in a permanent state of tension.

The inhuman behavior begins as soon as one steps into prison, with the assumption that every person who has entered the prison is a criminal, and that one who utters a syllable against this inhuman behavior has to bear strict punishment and insults. All of us went through this inhuman behavior. We have, through our struggle, from the very beginning, compelled the system to behave with us humanely and in accordance with law. We have proven to be a great nuisance to the system, leading the administration to harbour great animus towards us, but we have also earned a position of respect among the hearts of many of the prisoners.

This is because the movement for equality has sown the concepts of “self and society” and “individualism and collectivism.” It is therefore necessary to underline the import of the collectiveness, of the unity and of the preparedness of these struggles of the Elgar prisoners. This, I would say, is because the reality here is more intense, more serious, more extreme and more challenging.

People here die due to lack of treatment and the system here does not even experience a scratch. Many here rot for days on end because court hearings do not take place, and due to lack of proper legal aid. The system here does not in the least care about human lives rotting and dying away. Everything is suppressed in a planned manner. It is repressed. There is a massive administrative net of a commonality of interests from the bottom to the top, from inside to outside that is ever ready to support the prison system. Many things are managed, many things are settled.

The screen of the impenetrable walls comes in handy to cover up the injustices and illegalities. This system does not allow any organised resistance to take shape against the injustices here. The prison is ever alert about this. The 24-hour watch, the net of CCTV cameras, the unofficial network of informers is all used very efficiently. Any possibility of resistance is halted. The prison immediately becomes very ferocious against any voice of resistance rising in opposition.

Punishment is meted out arbitrarily for this. The prison imposes punishments such as naalbandhi—the practice of directing prisoners to wedge their feet between the iron bars of a gate or barrack, and then beating them on their soles with batons; beating with a thick canvas belt; solitary confinement for an indefinite period; stopping of visits, letter correspondence and court dates; mental torture; externment from a circle; changing of circle; confiscation of books; and so on.

Here, hurting the ego of the jail is also a major crime. The ego of the prison administration is of a police-like nature—the ego of the khaki uniform, the ego of being on a police officer’s post. With this ego, the prison uses whatever means it can to force every prisoner to succumb and survive by prostrating himself. Here, you have to obey what the officer says, do as the officer orders. This is the way of the police. No asking for any clarifications: Why? For what? Such questions must not be asked. And never say, “I will not accept this order.” Any such action hurts the ego of prison administration; and if the ego of the prison is hurt, they will become all the more inhuman with you.

You become a target of the prison and the prison uses its power to keep an eye on you, in order to suppress you. It becomes active and alert, to give you trouble and mental tension at every stage. For example, when you return to jail from court and your body search is done at the Lal Gate—the main entry gate—you are made to remove all your clothes and stand in your underwear, and the guard there pulls open your underwear to see if there is anything there. He starts examining, he gropes your private parts with his hands, and sometimes he puts his finger into your anus and feels around thoroughly. You have to endure all this. The CCTV cameras at the gate, the female staff at the gate, the bright lights at the gate, meaning everything is totally open and in the midst of all this, you have to stand naked—even if it does not accord with any rules, yet you have to follow it. For if you do not, the ego of the prison is hurt.

The prison very casually perpetrates this assault on one’s self-esteem and self-respect, and easily digests such unlawful activity. This act of stripping off a prisoner’s clothes with a casual “how did it go” is actually a salve to the prison’s ego. These forceful acts to assuage the prison’s ego are practiced elsewhere too—such as squatting half-naked in the checking hall in front of the superintendent; waiting without footwear in front of a senior officer or outside his office; witnessing all your belongings being thrown around here and there, upside down, during barrack searches; not saying a word about the falling standards of the daily tea and breakfast; eating without any complaint the half cooked chapattis and tasteless bhaji and dal; keeping quiet regarding the adulteration of the milk; tolerating the corrupt practices going on in the prison canteen being run on a no-profit, no-loss basis. All in all, tolerating all the corrupt and illegal practices and treatment of the prison is caressing the ego of the prison. It is a serious crime to hurt the ego of the prison. We have committed this serious crime several times, and have been targeted by the prison for it, vengefully sent here and there.

Imprisonment carries with it another painful hideousness—separation. The reality of separation, of an existence of enduring the torture of staying apart from one’s life-partner, wife, lover, pierces like a thorn at every step inside prison. Only twenty minutes of a countdown-like meeting. What exactly to say? And what to listen to? How much should one see? How much to store in the mind’s eye? It all flies past in a flurry. The twenty minutes go by in the chaos of somehow stitching together the points about court issues, other necessities, and conveying messages of various others. The prison employees and officers at the meetings sharply cut off your phone. The dialogue building up in your heart is broken off in a moment, and you are left speechless and helpless, looking through the glass before you, at the face of your loved one.

There is only the glass of a window between the two, but it becomes impossible to cross that tiny distance and even give a hug to your dearest. You silently say bye with your eyes and hands, and leaves, and then remembers that in all that hurry, you forgot to even ask “how are you?”

A calmness takes over the soul. The heart eats itself out. A great anger of the self on the self surges and takes over. Light tears spill out. Separation becomes dreadful, like the pricks of thousands of thorns. It is the same for everyone. The burden of separation has to be borne by the accused facing trial—the undertrial prisoner who, despite being innocent, has to tolerate this—and also by the life-partner, who despite not being an accused, despite not having any offence, has to live the torment of separation. The prison, the court, no machinery spares a humane thought about this.

Letters are read line by line by the officers here, so there is a watch on writing too. The suffocation and restlessness of the mind of the prisoner is not seen in the open, but the scale of this restlessness is immense. But this restlessness is like some incurable disease that keeps on growing its disfiguring presence within the soul. A person laughing from the outside is internally troubled, sad and drifting at a loose end. He does not get a space, a refuge that can bring him peace of mind. Nights are desolate and agitated, days are blank and empty, somewhat like Gulzar’s song: “Din khaali khaali bartan hain, raat hai jaisa andhaa kua”—Days pass like empty vessels, nights are like dark wells.

Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi (That dawn will eventually break)

So, all in all, there is no reason to have any misunderstanding or lack of clarity regarding this repression. Who are the enemies? And who are the friends? This has been brought forth clearly by these times. It was not that this was not so earlier; but this period, particularly prison, has given a good space for thought and that thought has given a good opportunity for making one’s own political and emotional analysis. My words may suggest that everything is very negative. Indeed, the situation is filled with negativity, but the torch of positivity and hope in one’s mind also remains burning in these dark times. The energy for keeping that flame alive has been provided by the movement.

Despite this suffocating, enclosed, inhuman atmosphere, I have been able to creatively preserve myself as an artist activist. I have received very valuable assistance from the family of the movement outside prison and of the family of Elgar prisoners within it. I have been able to write about this prison, to write poems about this phase of repression, to read a lot, and to discuss things calmly with experienced senior persons of the movement.

I have learnt many new things from such discussions—concepts became much clearer, I got the answers to unanswered questions, and I now understand the past of the egalitarian movement closely and somewhat deeply. I have been able to grasp every feeling on my mind peacefully and calmly, in a very beneficial manner, and to delve deeper into understanding the concept of living together.

By this I mean to say that I have not been able to do much and yet I have, even in this captivity, been able to do quite a bit. Prison injures a lot of your things. It keeps a constant watch on your every expression. Yet our expression could pierce past these walls and reach the people outside. It was a source of great inspiration to us that our words, our poems, our calls to struggle could cross these massive stone walls and reach the people, and that the people paid heed to and embraced our expression. That the people did not allow us to be cut off from them and that our links with the people remain strong till today is something that gives us a strong basis to persevere.

Though this repression has isolated us from the broad people’s movement and kept us alone in jail, I do not look at this repression at a personal level at all. I look at this repression as a part of the wide-ranging repression being carried out in the country by this fascist state. Thousands of people’s agitations have taken place since 2014 against the neo-Peshwai in central cities like Delhi, Mumbai and in various corners of the country.

The people throughout the country have raised the call for struggles against hundreds of injustices and repressive acts, against displacement, against anti-people laws, against illegal encounters and torture, against the commercialisation and Brahmanisation of education, against the anti-constitutional cultural politics of the Manuvaadi forces, and against the government-backed conspiracies of the central investigative agencies. Every such call has been met by state repression—in these circumstances, one clearly feels that the repression meted out to the Elgar prisoners is but a part of this broader repression.

I am not despondent because my estimations and my understanding of the movement carry the mature intent of the history of many thousand years of revolutionary struggles. This understanding reminds me continuously, over and over, of the revolutionary stories of people’s struggles fought firmly against repression, and of the ideals of those leading them.

This historical fighting aim does not allow the agitating, struggling artist-activist in me to die. It helps me hold out against the suffocating besieged prison atmosphere. And I am proud that this is the mental state of all of us BK-16 Elgar prisoners.

Sometime in the Anda Cell of the Taloja Central Jail, the electricity would go out suddenly at seven or eight at night, and the already uncertain atmosphere would become frightfully silent. In such quiet surroundings, one feels terribly alone. In that deep darkness, only the iron bars can be seen. Normally nothing can be done on such frightful nights. A momentary utopia struggles to achieve domination over existence. With flitting eyes, one starts fumbling with thoughts that start helplessly churning.

The prison starts dominating in a dreadful manner. In such an oppressive setting of solitude, my inner mind goes blank and I become forced to sit with my head tucked in. I would start sinking into my own cocoon, but just then, the high-pitched tone of Sudhir would tear apart that frightful darkness and reach out, carrying a beacon of light to me.

The song would be of Sahir: “Sar jhukane se kuch nahin hota hai, Sar uthao tho koi baat banein”—(Nothing has comes from bowing your head; Something can come from holding your head high). The song would lift the spirits of the whole Anda Cell listening to him.

Then, Sagar would start: “Ye dastoor ko, subah be-noor ko, mai nahin maanta, main nahin jaanta”—(Such a norm, this lightless morn; I do not respect, I do not accept). Then Gadling sir would begin his recitation of Kabir’s couplet: “Nadiya naav mein doob jaaye re”—(The river is drowning in the boat). Gautam would then elevate the mood with “Woh subah kabhi to aayegi”—(That dawn will eventually break). Then I would sing the song, “Mera rang de basanti chola”—(Give my robe the colour of spring).

Song would join song and person would link up with person. The feeling of loneliness would be hurled far away; because song, with its sublime scent of the collective spirit would pervade. For those in the Anda Cell hearing a song for the first time, it would carry something new, for those who had heard it before, the old would be rediscovered anew. The dark empty night of the Anda Cell would, with these meaningful songs, grow intense with intent. And on such a night, some lines would blossom from the heart…

Mashaali vizhlya nahit ajunhi

Damanamagun daman zari

Dhag uraauraat ajunhi

Turung punha punha zari

(The torches have not yet dimmed

though repression follows repression

The flame is alive in every part

though imprisonment follows imprisonment)

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.