Better killed than homeless: The struggle of forest dwellers in Indian controlled Kashmir

In this essay, Adil Hussain documents the challenges facing the tribal communities who live in the forests of Indian controlled Kashmir. A new resolution of the Indian government declared them illegal occupants, putting them at risk of eviction and homelessness after depending on these lands for generations.

Fear gripped Kani Dajjan village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district on 4 December 2020 as it swarmed with Indian government officials armed with axes. By the time they left, 10,000 trees were slashed. For Muhammad Ahsan, however, “officials did not cut trees, but uprooted families.”

Fear gripped Kani Dajjan village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district on 4 December 2020 as it swarmed with Indian government officials armed with axes. By the time they left, 10,000 trees were slashed. For Muhammad Ahsan, however, “officials did not cut trees, but uprooted families.”

For people like Ahsan, the 75 years old village head of Kani Dajjan, the world has ended and “homelessness is the new reality.”

The Indian government’s decision to evict forest dwellers has jeopardized the life and livelihoods of the communities who have been living on the mountains of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) for centuries. Authorities claim that those living in the forests are illegal occupants while the forest dwellers, who are currently facing the State’s wrath, told me that they have been there even when “India was yet to come into existence.” The government’s decision is not to be seen in isolation, but as part of a larger plan of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government to drive demographic change in Jammu and Kashmir, the only state in the Indian union whose population is for the majority Muslim.

The fear of homelessness has now become real after forest dwellers of Zilsidara and Kani Dajjan in central Kashmir’s Budgam district and tribal villagers of Pahalgam in south Kashmir have been issued eviction notices.

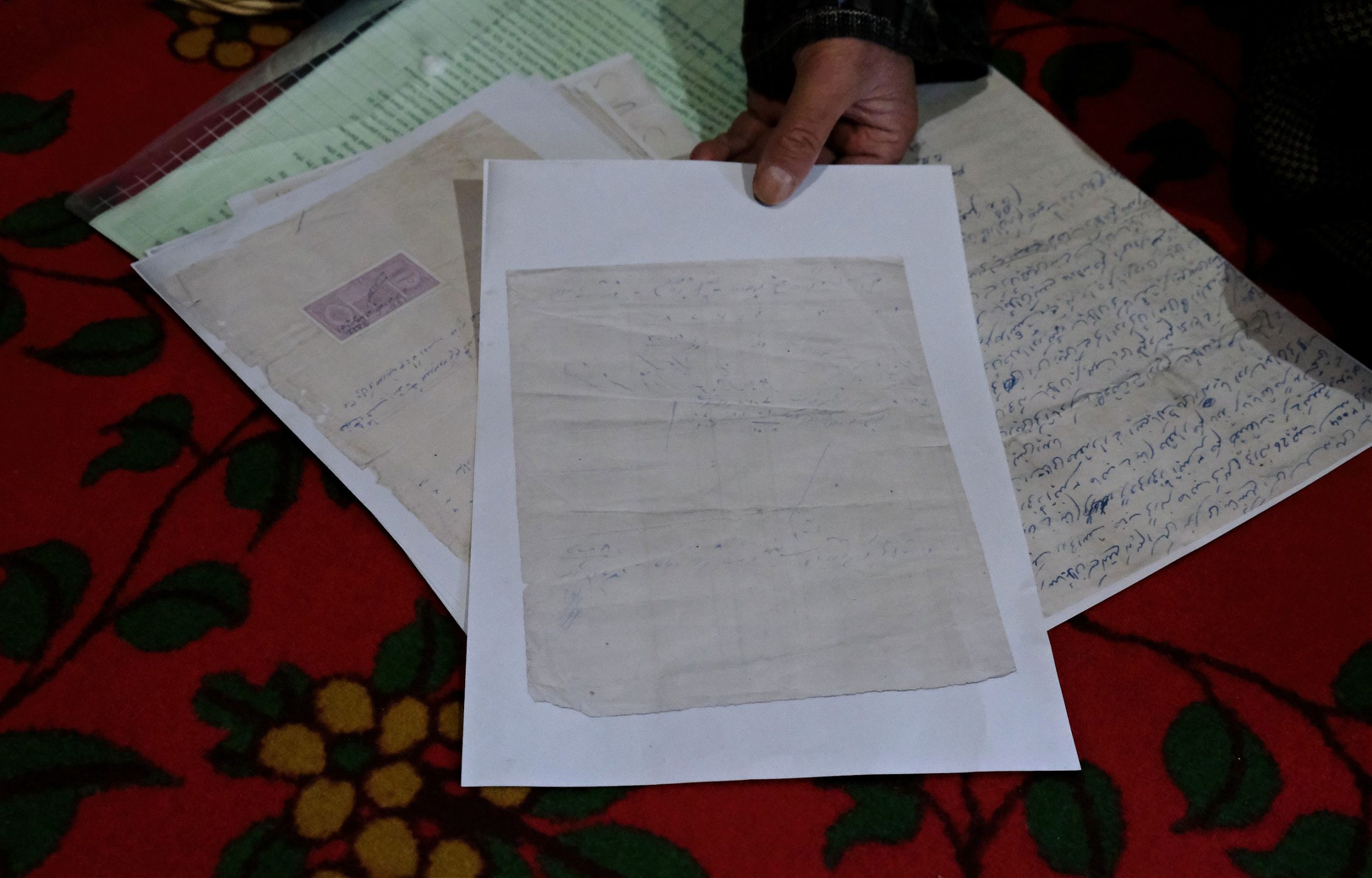

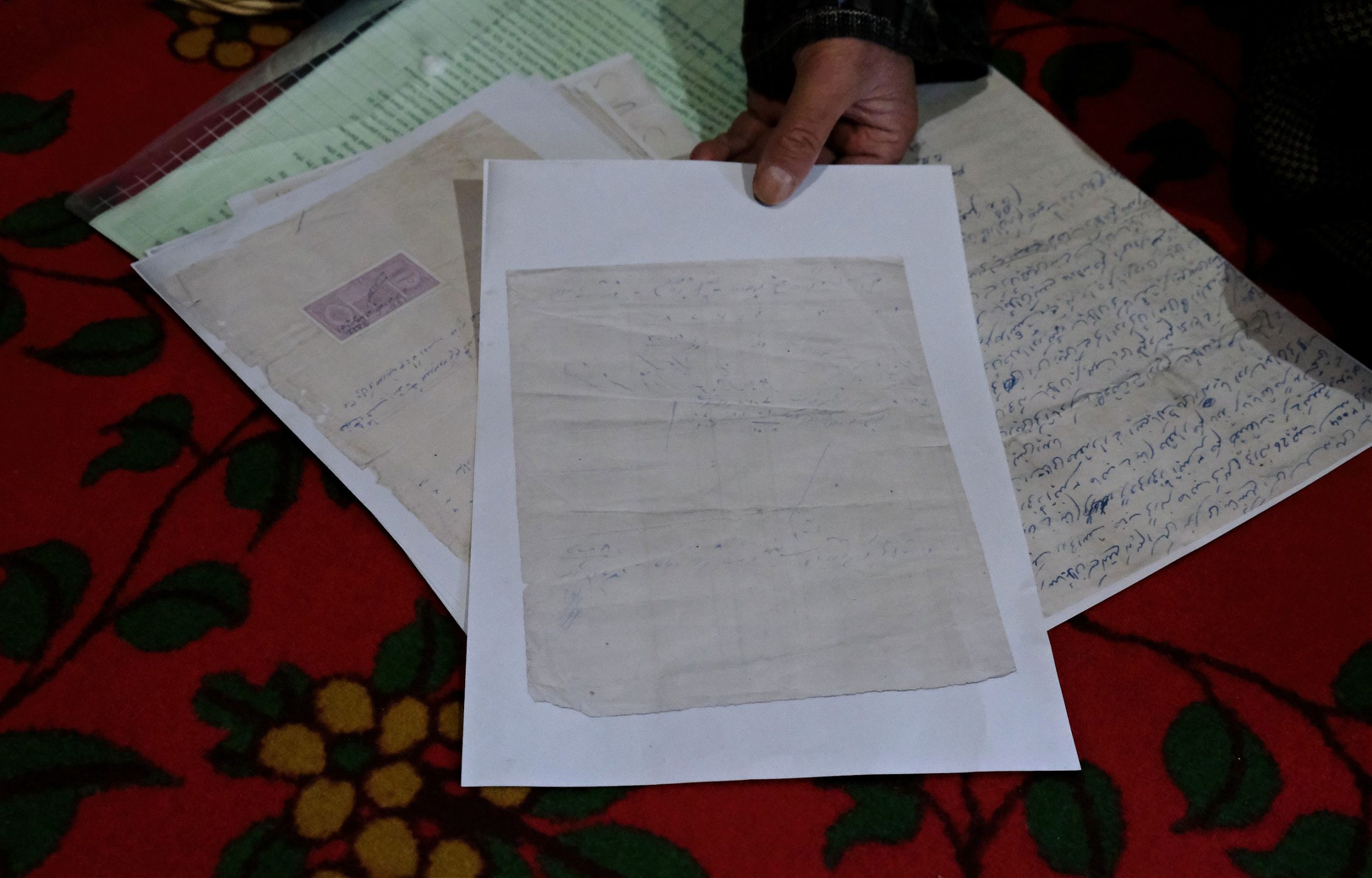

According to Ahsan, indigenous people were provided land holdings by the government in the early 1970s. “The land was provided under the Grow More Food scheme to empower the indigenous people of the region.”

According to the 2011 census, about 1.5 million tribal people live in Jammu and Kashmir – 12% of the total population. They depend on the forests for livelihoods and shelter and most of them do not own land or property. The Bakarwal community primarily rears goats and sheep while the Gujjars rear cattle – all activities that can partially or completely stop if these communities are evicted from forest lands.

Villagers told me that “the earth shook” for them when the government termed indigenous people as encroachers of forests and illegal occupants of the land. The government claims that 64,000 people have encroached 44,000 hectares of land illegally. According to official estimates, there are 2,017 hectares in Ramban, 1,974 in Rajouri, 1,473 in Poonch, 1,496 in Anantnag, 1,027 in Shopian, 655 in Pir Panjal, 578 hectares in Kamraj and 500 hectares Jammu respectively that would have to be cleared from forest encroachments.

“We lived here when India was still under the British Rule and today we are told we are the illegal occupants?” Zooni Begum, 108, questioned the logic behind the government’s actions. “Why don’t they kill us all? Better than being homeless.”

Environmental activist Dr Raja Muzaffar believes that the government seems inclined to implement only dreaded laws and not the laws that protect the rights of the people. Dr Muzaffar says that the Forest Rights Act (FRA) has been implemented in Jammu and Kashmir months after government officials damaged the orchards and sent eviction notice to the forest dwellers. Under the FRA, in fact, traditional forest dwellers are protected against forced displacements and have the right to grazing, access to water resources and access to forest products other than timber.

In August 2019 the Narendra Modi government deprived the region of its semi-autonomous constitutional guarantee. Soon afterwards the government started the implementation of a new domicile law that grants to non-local residents of Kashmir citizenship and government jobs. This has been interpreted on many fronts as an attempt to bring demographic change in India’s only Muslim-majority region.

Mohammad Akbar, a 55-year-old resident of Zilsidara village, is one of those who was served eviction notice. He told me that his community fears that their fate will be same as that of the neighboring forest community in Kani Dajjan, where members of the Armed Forces along the government officials axed their orchards and uprooted the trees in early December 2020. “The government can do anything with the support of guns,” Akbar said.

For tribal activist Zahid Parwaz Choudhary, it is a “reign of terror that has been unleashed against poor Gujjar and Bakerwals across Jammu and Kashmir.” The two main pro-India political leaders from the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party also contested the government’s move to evict tribal people, claiming that these tribes have been living in the forests for 200 years. There is, however, no relief for these tribal communities and no one has come forward to save them from eviction. As anti-encroachment orders are being implemented, becoming homeless seems the only future for these communities.

The forest dwellers fear that government wants to settle outsiders on the land after cutting their trees, Akbar told me after an online media report on 16 December 2020 stated that the Jammu and Kashmir government has marked land for the Sainik Colony in Budgam district. According to a senior government officer, this colony is primarily set up to provide housing facilities to retired armed forces personnel and their families. The colony will also cater to widows and families of deceased armed forces personnel, suggests the same media report.

These evictions will not only leave a large portion of the population homeless, but they will also add to the growing fear that the BJP government is all out to change the demography of Jammu and Kashmir.

Related Posts

How Green Laws and Carbon Markets Being Used to Prosecute Indigenous Land Defenders in Global South

Better killed than homeless: The struggle of forest dwellers in Indian controlled Kashmir

Fear gripped Kani Dajjan village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district on 4 December 2020 as it swarmed with Indian government officials armed with axes. By the time they left, 10,000 trees were slashed. For Muhammad Ahsan, however, “officials did not cut trees, but uprooted families.”

Fear gripped Kani Dajjan village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district on 4 December 2020 as it swarmed with Indian government officials armed with axes. By the time they left, 10,000 trees were slashed. For Muhammad Ahsan, however, “officials did not cut trees, but uprooted families.”

For people like Ahsan, the 75 years old village head of Kani Dajjan, the world has ended and “homelessness is the new reality.”

The Indian government’s decision to evict forest dwellers has jeopardized the life and livelihoods of the communities who have been living on the mountains of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) for centuries. Authorities claim that those living in the forests are illegal occupants while the forest dwellers, who are currently facing the State’s wrath, told me that they have been there even when “India was yet to come into existence.” The government’s decision is not to be seen in isolation, but as part of a larger plan of the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government to drive demographic change in Jammu and Kashmir, the only state in the Indian union whose population is for the majority Muslim.

The fear of homelessness has now become real after forest dwellers of Zilsidara and Kani Dajjan in central Kashmir’s Budgam district and tribal villagers of Pahalgam in south Kashmir have been issued eviction notices.

According to Ahsan, indigenous people were provided land holdings by the government in the early 1970s. “The land was provided under the Grow More Food scheme to empower the indigenous people of the region.”

According to the 2011 census, about 1.5 million tribal people live in Jammu and Kashmir – 12% of the total population. They depend on the forests for livelihoods and shelter and most of them do not own land or property. The Bakarwal community primarily rears goats and sheep while the Gujjars rear cattle – all activities that can partially or completely stop if these communities are evicted from forest lands.

Villagers told me that “the earth shook” for them when the government termed indigenous people as encroachers of forests and illegal occupants of the land. The government claims that 64,000 people have encroached 44,000 hectares of land illegally. According to official estimates, there are 2,017 hectares in Ramban, 1,974 in Rajouri, 1,473 in Poonch, 1,496 in Anantnag, 1,027 in Shopian, 655 in Pir Panjal, 578 hectares in Kamraj and 500 hectares Jammu respectively that would have to be cleared from forest encroachments.

“We lived here when India was still under the British Rule and today we are told we are the illegal occupants?” Zooni Begum, 108, questioned the logic behind the government’s actions. “Why don’t they kill us all? Better than being homeless.”

Environmental activist Dr Raja Muzaffar believes that the government seems inclined to implement only dreaded laws and not the laws that protect the rights of the people. Dr Muzaffar says that the Forest Rights Act (FRA) has been implemented in Jammu and Kashmir months after government officials damaged the orchards and sent eviction notice to the forest dwellers. Under the FRA, in fact, traditional forest dwellers are protected against forced displacements and have the right to grazing, access to water resources and access to forest products other than timber.

In August 2019 the Narendra Modi government deprived the region of its semi-autonomous constitutional guarantee. Soon afterwards the government started the implementation of a new domicile law that grants to non-local residents of Kashmir citizenship and government jobs. This has been interpreted on many fronts as an attempt to bring demographic change in India’s only Muslim-majority region.

Mohammad Akbar, a 55-year-old resident of Zilsidara village, is one of those who was served eviction notice. He told me that his community fears that their fate will be same as that of the neighboring forest community in Kani Dajjan, where members of the Armed Forces along the government officials axed their orchards and uprooted the trees in early December 2020. “The government can do anything with the support of guns,” Akbar said.

For tribal activist Zahid Parwaz Choudhary, it is a “reign of terror that has been unleashed against poor Gujjar and Bakerwals across Jammu and Kashmir.” The two main pro-India political leaders from the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party also contested the government’s move to evict tribal people, claiming that these tribes have been living in the forests for 200 years. There is, however, no relief for these tribal communities and no one has come forward to save them from eviction. As anti-encroachment orders are being implemented, becoming homeless seems the only future for these communities.

The forest dwellers fear that government wants to settle outsiders on the land after cutting their trees, Akbar told me after an online media report on 16 December 2020 stated that the Jammu and Kashmir government has marked land for the Sainik Colony in Budgam district. According to a senior government officer, this colony is primarily set up to provide housing facilities to retired armed forces personnel and their families. The colony will also cater to widows and families of deceased armed forces personnel, suggests the same media report.

These evictions will not only leave a large portion of the population homeless, but they will also add to the growing fear that the BJP government is all out to change the demography of Jammu and Kashmir.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.