Astria Suparak On The Role Of Sports In Upholding Empires And Systems Of Power

Astria Suparak is a Thai multidisciplinary artist, writer, and curator based in Oakland, California. With a bent for exploring science, politics, and community activism through pop culture and mainstream headlines, the interdisciplinary artist first came to my attention for her 2020 project Asian Futures, without Asians, a multipart research project comprising videos, installations, and other visual mediums. It analyzes American science fiction cinema and draws from the histories of art, architecture, design, fashion, film, food, and weaponry to reveal the racist tropes deeply ingrained in Western visual culture.

Suparak’s most recent curatorial work explores the political flows of the globalized sports-media complex. Created in collaboration with Brett Kashmere, The Game is Not the Thing: Sport and the Moving Image has been displayed at Walker Center in Minneapolis, MN. After the Summer Olympics, sports media and brands spent millions of dollars investing in heroic portrayals of athletes and sportswashing campaigns that position sports as the great unifier. Watching these hagiographic stories in the face of continued genocides felt egregious, especially as the International Olympic Committee maintains that the mega-event is not a place for politics nor resistance.

Sports have always been political. In the last 5 years alone, major U.S. outlets flocked to cover historic moments at the intersection of sports and power, such as President Barack Obama intervening to end an NBA wildcat strike in the wake of the murder of Jacob Blake, or the Justice Department settling the over 100 claims by women who endured sexual abuse committed by USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar.

In their curatorial essay that accompanies their exhibition, Suparak and Kashmere go deeper into the politics behind sports:

“Who gets to play? Who is penalized for what? Where are stadiums built? And with whose money? Eminent domain, drug and gender testing, antitrust exemptions, corporate sponsorships, tax breaks, bribery, and abuse scandals are just some of the ways power is flexed daily within what has been called a secular religion and a proxy for war.”

There are more mega-events to come. With the FIFA World Cup in 2026 and the Olympics in 2028, we will continue to be inundated by sportswashing campaigns. Amid the gaining momentum for unchecked celebrations, Suparak and Kashmere explore the paradoxical nature of sport—as a site of biopolitical control, collective struggle, and individualized fantasy—and its role as a vessel for such utopic narratives.

The Game is Not the Thing: Sport and the Moving Image exhibits an important breadth of work, from experimental media to nontheatrical cinema, that offers a counternarrative to sports as a wholesale celebration. Take The Nation’s Finest by Keith Piper, a short video mimicking the look of state propaganda to critique the way predominantly white countries use Black bodies to embrace national pride while simultaneously disenfranchising their Black residents. Suparak and Kashmere also bring older films to the surface, such as Charles Dekeukeleire’s 1927 cinematic poem Combat de Boxe, which uses negative images to share a raw perspective of the aesthetics of boxing.

In this regard, sports and arts have much in common: they are both sites of pleasure, passion, and resistance. Suparak and Kashmere show sport’s potential to transcend the shortsighted zero-sum narrative of losers and winners and as a refuge from the world’s troubles.

I spoke to Suparak about the counter-narratives from artists she’s found through her curation work, the Western fascination for utopian narratives, and how sports and the arts are not mutually exclusive sources of inquiry and criticism of our political and cultural spheres. What follows is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

Lisa Kwon: Did you grow up playing any sports?

Astria Suparak: I do not have an athletic background but have made sports-related work for a couple of decades, mostly from an anthropological angle by looking at the political and social aspects of sports. This includes curating the exhibition, “Whatever It Takes: Steelers Fan Collections, Rituals, and Obsessions” in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, creating various artist projects and wearables, and organizing sports-themed screenings, discussions, and other events. Many sports-related projects are with my co-curator Brett Kashmere, including an abstract installation overlaying various sports goals, which we’re currently revisiting for an upcoming exhibition in Ontario, Canada.

LK: What initially inspired this curation work around sports media?

AS: In 2018, Brett and I co-edited a special issue of INCITE Journal of Experimental Media on sports, looking at various intersections between sports, media, art, performance, and popular culture. We made the case that there has been a shift in the way that sports have been taken up as a subject of inquiry in recent decades, both in academia with the rise of critical sports studies and in the art world. Art historian Jennifer Doyle has termed this “the athletic turn in contemporary art.” In the years since, we’ve witnessed an explosion of sports-related content in art spaces.

Our personal histories with sports also inform and frame this curatorial project. Brett’s research and artmaking reframe dominant narratives about sports, such as hockey violence and Canadians’ self-image as peaceful; the intertwined and mutually influencing histories of basketball and hip hop; and American football, race, and identity. He was a child athlete in Canada, playing hockey for over a decade then switching to basketball as a teenager. Later he coached girl’s basketball.

Part of our shared interest in sports is its persistent misrepresentation as benign, apolitical, and a refuge from the real world.

LK: Did you go into this work with Brett knowing that you would find something larger about sports media’s role in furthering imperialism and upholding hierarchies and hegemonies?

AS: Sports are constantly being used to uphold empires and systems of power. We take sports media’s role in furthering imperialism and upholding hierarchies, classifications, and hegemonies as a given. This recognition comes out of our own research and experiences with sports and by looking at artists’ work and other forms of critical analysis and commentary.

There is a lot of good scholarship on this topic. For instance, Varda Burstyn writes about the “sports nexus”—a web of lucrative “interdependent relationships between the athletic, industrial, and media sectors” that combines cultural and economic influence to assert an elitist, hypermasculine account of power and social order. There are a lot of great podcasts that bring expansive political, feminist, and cultural perspectives to the subject of sport and society, including Dave Zirin’s Edge of Sports, Derek Silva, Johanna Mellis, and Nathan Kalman-Lamb’s The End of Sport, and Burn It All Down, which is hosted by Shireen Ahmed, Lindsay Gibbs, Brenda Elsey, Amira Rose Davis, and Jessica Luther.

LK: What common themes did you unearth while engaging with these scholarly works and popular texts?

AS: Our series for the Walker includes themes such as the confluence of nationalism, militarism, spectacle, and sport; activist resistance to sport’s hegemonic tendencies; the complex imbrications of sports, race, gender, and representation; the fetishized spectacle of the ideal athletic body; the ways in which regional sporting events and traditions—like Senegalese wrestling—serve as occasions for collective catharsis and cultural expression; and formalist interventions into sports media imagery.

LK: What insights have you gained from finding artists who use nontraditional mediums to say something about sports?

AS: Some of today’s most powerful and insightful critiques on sport and its media exist within experimental film, artists’ cinema, video art, and moving image installation. I’m thinking of works like Harun Farocki’s Deep Play (2007) and Sondra Perry’s IT’S IN THE GAME ’17 (2017), to name a few examples. These projects bring new formal, poetic, and strategic approaches to analyzing mediated sports while opening the work to new audiences and potential for exchange between theory and practice.

LK: How would you describe sport’s relationship with the arts?

AS: There is a longstanding idea that the worlds of sport and art are mutually exclusive, but there have always been artists interested in the political and aesthetic valences of sport. These artists approach the subject from a position immersed in sports culture and critically aware fandom, rather than cynicism. I think the combination of deep investment with a willingness to raise questions and challenge commonplace assumptions distinguishes this work from mainstream sports documentaries and fiction films, which are ultimately produced to serve corporate interests and generate money.

On the other hand, artists can also bring forward the creative, communal, and utopian potentials of sport. Play for the sake of play and non-zero-sum games. Reimagining what sports can do and be, and who they can serve. Some of the works in our No Goal program demonstrate this tendency.

LK: Who are some artists that you’d like to uplift from your curation work that share interesting perspectives on the paradoxical nature of sports?

AS: Haig Aivazian’s work is critical to understanding the complex interplay of nationalism, militarism, spectacle, and sport. His 2019 video collage essay, Prometheus, juxtaposes archival footage and sound from the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 1991 and the 1992 Olympic games, which prominently featured the American “Dream Team” to expose the various ways the U.S. employs hard and soft power, including sports, in the geopolitical sphere.

Haig’s lecture performance World/AntiWorld: On Seeing Double, our second program in The Game is Not the Thing series, examines how professional sports, public space, and the law converge with the history and future of surveillance and weapons systems. One example is the ball and player tracking systems that revolutionized sports management, coaching, and training practices, contributing to the rise of data-driven analysis and strategy. It was adapted by former IDF soldiers from an Israeli missile tracking technology.

The recent Israeli attacks on Lebanon, where Haig lives, and Palestine underline how resonant his work is and illuminates how countries like Israel use surveillance technology for both war and civilians.

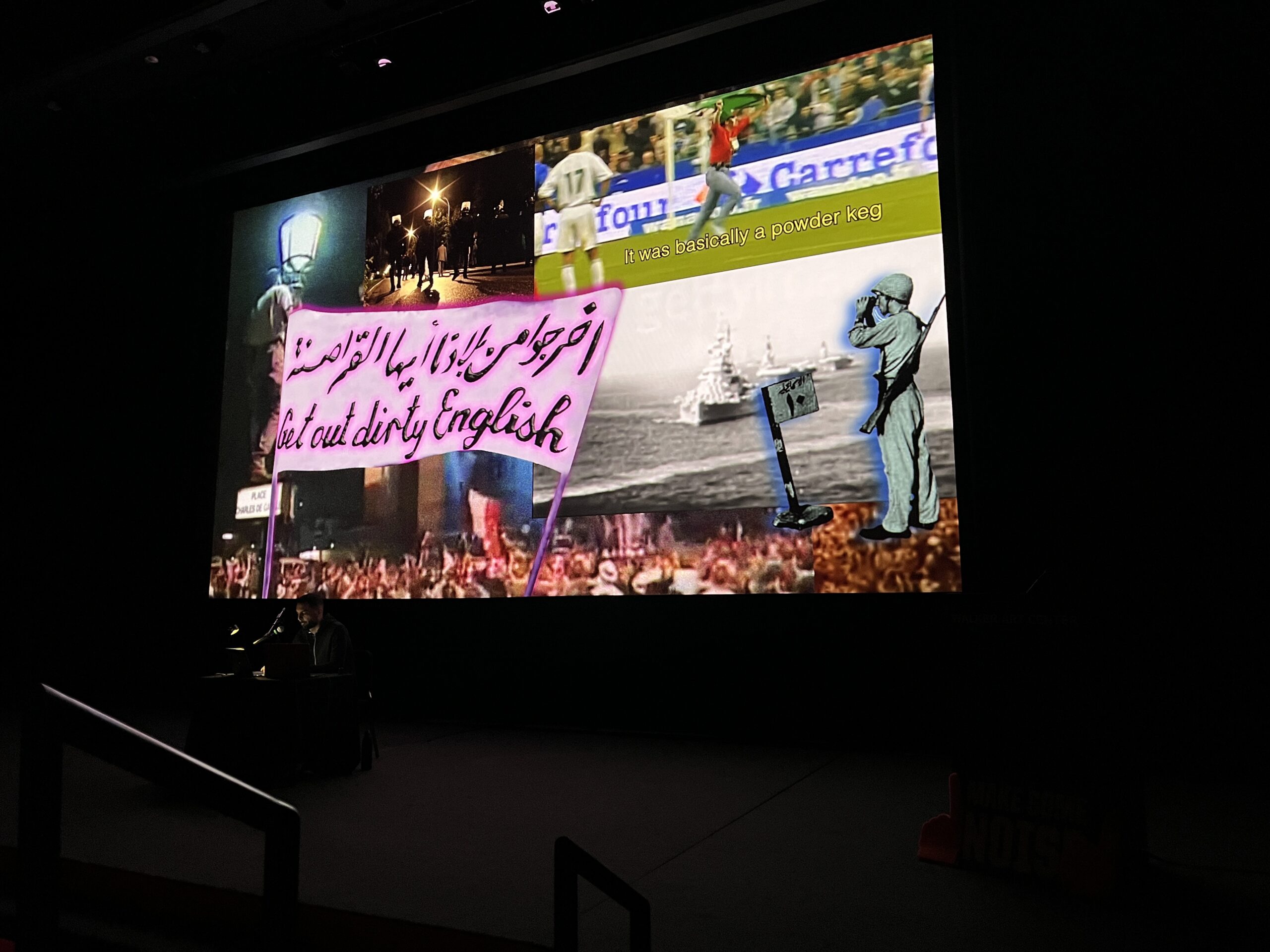

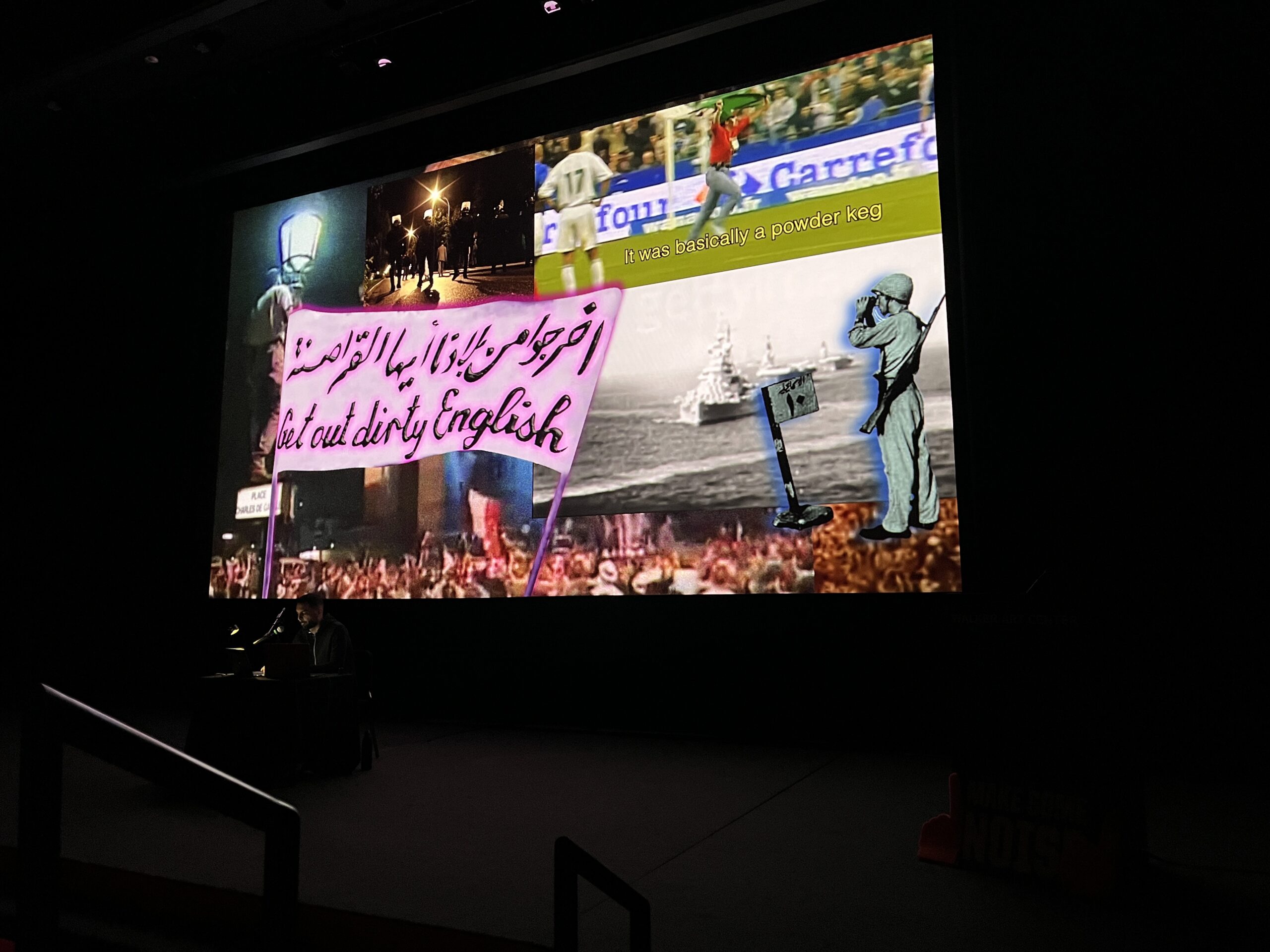

I also point to the artists in the Power Plays program, which interrogates how sports function as a site for control, struggle, and collective fantasy. The Nation’s Finest (1990) by Keith Piper mimics the look and tone of state propaganda with a silky, biting critique of the way predominantly white countries use black bodies in the service of national pride while simultaneously disenfranchising their black residents. Youthupia: an Algerian Tale (2020) by Fethi Sahraoui shows how sports fans in Algeria participated in the largest popular uprising against a president and how those fans created political protests based on soccer cheers. Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s The Same Track (2022) considers how British colonies and commonwealth states are used and manipulated by the British Empire.

LK: Why do you think the world has opted for a hagiographic approach to sports narratives over more experimental or honest portrayals of them?

AS: Comfort is one major factor. For many, sports provide a temporary haven from political, social, and economic concerns and the stresses of everyday life. This aligns with a tradition of writing about sports, mainly from the left, that has considered sport “an opiate of the masses” and a distraction from the more significant aspects of life. A prevailing attitude among sports fans and commentators entails that athletes should “shut up and play,” and that sports should be maintained and treasured as a refuge from politics. This attitude ignores the fact that sports are always already political. Sports are used for political purposes and offer an important site of struggle that often goes unrecognized or underreported. But it’s easier to focus on the stories of exceptional individuals, coaches, and teams, rather than on the messy contextual, structural, and intersectional forces that enable such popular narratives.

We discuss one such narrative in our curatorial essay for the Walker, with the ESPN Films—Netflix hagiography The Last Dance (2020), which chronicles Michael Jordan’s rise to superstardom as a member of the 1990s Chicago Bulls. The viewer is shepherded through this recent history by Jordan’s indignant responses to trivial and imagined infractions and in the process, reinscribes the supremacy of his mythology and brand. If the goal is to make a self-serving, celebratory portrait of oneself that furthers one’s own power and financial interests, it’s an effective approach.

Related Posts

Astria Suparak On The Role Of Sports In Upholding Empires And Systems Of Power

Astria Suparak is a Thai multidisciplinary artist, writer, and curator based in Oakland, California. With a bent for exploring science, politics, and community activism through pop culture and mainstream headlines, the interdisciplinary artist first came to my attention for her 2020 project Asian Futures, without Asians, a multipart research project comprising videos, installations, and other visual mediums. It analyzes American science fiction cinema and draws from the histories of art, architecture, design, fashion, film, food, and weaponry to reveal the racist tropes deeply ingrained in Western visual culture.

Suparak’s most recent curatorial work explores the political flows of the globalized sports-media complex. Created in collaboration with Brett Kashmere, The Game is Not the Thing: Sport and the Moving Image has been displayed at Walker Center in Minneapolis, MN. After the Summer Olympics, sports media and brands spent millions of dollars investing in heroic portrayals of athletes and sportswashing campaigns that position sports as the great unifier. Watching these hagiographic stories in the face of continued genocides felt egregious, especially as the International Olympic Committee maintains that the mega-event is not a place for politics nor resistance.

Sports have always been political. In the last 5 years alone, major U.S. outlets flocked to cover historic moments at the intersection of sports and power, such as President Barack Obama intervening to end an NBA wildcat strike in the wake of the murder of Jacob Blake, or the Justice Department settling the over 100 claims by women who endured sexual abuse committed by USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar.

In their curatorial essay that accompanies their exhibition, Suparak and Kashmere go deeper into the politics behind sports:

“Who gets to play? Who is penalized for what? Where are stadiums built? And with whose money? Eminent domain, drug and gender testing, antitrust exemptions, corporate sponsorships, tax breaks, bribery, and abuse scandals are just some of the ways power is flexed daily within what has been called a secular religion and a proxy for war.”

There are more mega-events to come. With the FIFA World Cup in 2026 and the Olympics in 2028, we will continue to be inundated by sportswashing campaigns. Amid the gaining momentum for unchecked celebrations, Suparak and Kashmere explore the paradoxical nature of sport—as a site of biopolitical control, collective struggle, and individualized fantasy—and its role as a vessel for such utopic narratives.

The Game is Not the Thing: Sport and the Moving Image exhibits an important breadth of work, from experimental media to nontheatrical cinema, that offers a counternarrative to sports as a wholesale celebration. Take The Nation’s Finest by Keith Piper, a short video mimicking the look of state propaganda to critique the way predominantly white countries use Black bodies to embrace national pride while simultaneously disenfranchising their Black residents. Suparak and Kashmere also bring older films to the surface, such as Charles Dekeukeleire’s 1927 cinematic poem Combat de Boxe, which uses negative images to share a raw perspective of the aesthetics of boxing.

In this regard, sports and arts have much in common: they are both sites of pleasure, passion, and resistance. Suparak and Kashmere show sport’s potential to transcend the shortsighted zero-sum narrative of losers and winners and as a refuge from the world’s troubles.

I spoke to Suparak about the counter-narratives from artists she’s found through her curation work, the Western fascination for utopian narratives, and how sports and the arts are not mutually exclusive sources of inquiry and criticism of our political and cultural spheres. What follows is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

Lisa Kwon: Did you grow up playing any sports?

Astria Suparak: I do not have an athletic background but have made sports-related work for a couple of decades, mostly from an anthropological angle by looking at the political and social aspects of sports. This includes curating the exhibition, “Whatever It Takes: Steelers Fan Collections, Rituals, and Obsessions” in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, creating various artist projects and wearables, and organizing sports-themed screenings, discussions, and other events. Many sports-related projects are with my co-curator Brett Kashmere, including an abstract installation overlaying various sports goals, which we’re currently revisiting for an upcoming exhibition in Ontario, Canada.

LK: What initially inspired this curation work around sports media?

AS: In 2018, Brett and I co-edited a special issue of INCITE Journal of Experimental Media on sports, looking at various intersections between sports, media, art, performance, and popular culture. We made the case that there has been a shift in the way that sports have been taken up as a subject of inquiry in recent decades, both in academia with the rise of critical sports studies and in the art world. Art historian Jennifer Doyle has termed this “the athletic turn in contemporary art.” In the years since, we’ve witnessed an explosion of sports-related content in art spaces.

Our personal histories with sports also inform and frame this curatorial project. Brett’s research and artmaking reframe dominant narratives about sports, such as hockey violence and Canadians’ self-image as peaceful; the intertwined and mutually influencing histories of basketball and hip hop; and American football, race, and identity. He was a child athlete in Canada, playing hockey for over a decade then switching to basketball as a teenager. Later he coached girl’s basketball.

Part of our shared interest in sports is its persistent misrepresentation as benign, apolitical, and a refuge from the real world.

LK: Did you go into this work with Brett knowing that you would find something larger about sports media’s role in furthering imperialism and upholding hierarchies and hegemonies?

AS: Sports are constantly being used to uphold empires and systems of power. We take sports media’s role in furthering imperialism and upholding hierarchies, classifications, and hegemonies as a given. This recognition comes out of our own research and experiences with sports and by looking at artists’ work and other forms of critical analysis and commentary.

There is a lot of good scholarship on this topic. For instance, Varda Burstyn writes about the “sports nexus”—a web of lucrative “interdependent relationships between the athletic, industrial, and media sectors” that combines cultural and economic influence to assert an elitist, hypermasculine account of power and social order. There are a lot of great podcasts that bring expansive political, feminist, and cultural perspectives to the subject of sport and society, including Dave Zirin’s Edge of Sports, Derek Silva, Johanna Mellis, and Nathan Kalman-Lamb’s The End of Sport, and Burn It All Down, which is hosted by Shireen Ahmed, Lindsay Gibbs, Brenda Elsey, Amira Rose Davis, and Jessica Luther.

LK: What common themes did you unearth while engaging with these scholarly works and popular texts?

AS: Our series for the Walker includes themes such as the confluence of nationalism, militarism, spectacle, and sport; activist resistance to sport’s hegemonic tendencies; the complex imbrications of sports, race, gender, and representation; the fetishized spectacle of the ideal athletic body; the ways in which regional sporting events and traditions—like Senegalese wrestling—serve as occasions for collective catharsis and cultural expression; and formalist interventions into sports media imagery.

LK: What insights have you gained from finding artists who use nontraditional mediums to say something about sports?

AS: Some of today’s most powerful and insightful critiques on sport and its media exist within experimental film, artists’ cinema, video art, and moving image installation. I’m thinking of works like Harun Farocki’s Deep Play (2007) and Sondra Perry’s IT’S IN THE GAME ’17 (2017), to name a few examples. These projects bring new formal, poetic, and strategic approaches to analyzing mediated sports while opening the work to new audiences and potential for exchange between theory and practice.

LK: How would you describe sport’s relationship with the arts?

AS: There is a longstanding idea that the worlds of sport and art are mutually exclusive, but there have always been artists interested in the political and aesthetic valences of sport. These artists approach the subject from a position immersed in sports culture and critically aware fandom, rather than cynicism. I think the combination of deep investment with a willingness to raise questions and challenge commonplace assumptions distinguishes this work from mainstream sports documentaries and fiction films, which are ultimately produced to serve corporate interests and generate money.

On the other hand, artists can also bring forward the creative, communal, and utopian potentials of sport. Play for the sake of play and non-zero-sum games. Reimagining what sports can do and be, and who they can serve. Some of the works in our No Goal program demonstrate this tendency.

LK: Who are some artists that you’d like to uplift from your curation work that share interesting perspectives on the paradoxical nature of sports?

AS: Haig Aivazian’s work is critical to understanding the complex interplay of nationalism, militarism, spectacle, and sport. His 2019 video collage essay, Prometheus, juxtaposes archival footage and sound from the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 1991 and the 1992 Olympic games, which prominently featured the American “Dream Team” to expose the various ways the U.S. employs hard and soft power, including sports, in the geopolitical sphere.

Haig’s lecture performance World/AntiWorld: On Seeing Double, our second program in The Game is Not the Thing series, examines how professional sports, public space, and the law converge with the history and future of surveillance and weapons systems. One example is the ball and player tracking systems that revolutionized sports management, coaching, and training practices, contributing to the rise of data-driven analysis and strategy. It was adapted by former IDF soldiers from an Israeli missile tracking technology.

The recent Israeli attacks on Lebanon, where Haig lives, and Palestine underline how resonant his work is and illuminates how countries like Israel use surveillance technology for both war and civilians.

I also point to the artists in the Power Plays program, which interrogates how sports function as a site for control, struggle, and collective fantasy. The Nation’s Finest (1990) by Keith Piper mimics the look and tone of state propaganda with a silky, biting critique of the way predominantly white countries use black bodies in the service of national pride while simultaneously disenfranchising their black residents. Youthupia: an Algerian Tale (2020) by Fethi Sahraoui shows how sports fans in Algeria participated in the largest popular uprising against a president and how those fans created political protests based on soccer cheers. Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s The Same Track (2022) considers how British colonies and commonwealth states are used and manipulated by the British Empire.

LK: Why do you think the world has opted for a hagiographic approach to sports narratives over more experimental or honest portrayals of them?

AS: Comfort is one major factor. For many, sports provide a temporary haven from political, social, and economic concerns and the stresses of everyday life. This aligns with a tradition of writing about sports, mainly from the left, that has considered sport “an opiate of the masses” and a distraction from the more significant aspects of life. A prevailing attitude among sports fans and commentators entails that athletes should “shut up and play,” and that sports should be maintained and treasured as a refuge from politics. This attitude ignores the fact that sports are always already political. Sports are used for political purposes and offer an important site of struggle that often goes unrecognized or underreported. But it’s easier to focus on the stories of exceptional individuals, coaches, and teams, rather than on the messy contextual, structural, and intersectional forces that enable such popular narratives.

We discuss one such narrative in our curatorial essay for the Walker, with the ESPN Films—Netflix hagiography The Last Dance (2020), which chronicles Michael Jordan’s rise to superstardom as a member of the 1990s Chicago Bulls. The viewer is shepherded through this recent history by Jordan’s indignant responses to trivial and imagined infractions and in the process, reinscribes the supremacy of his mythology and brand. If the goal is to make a self-serving, celebratory portrait of oneself that furthers one’s own power and financial interests, it’s an effective approach.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.