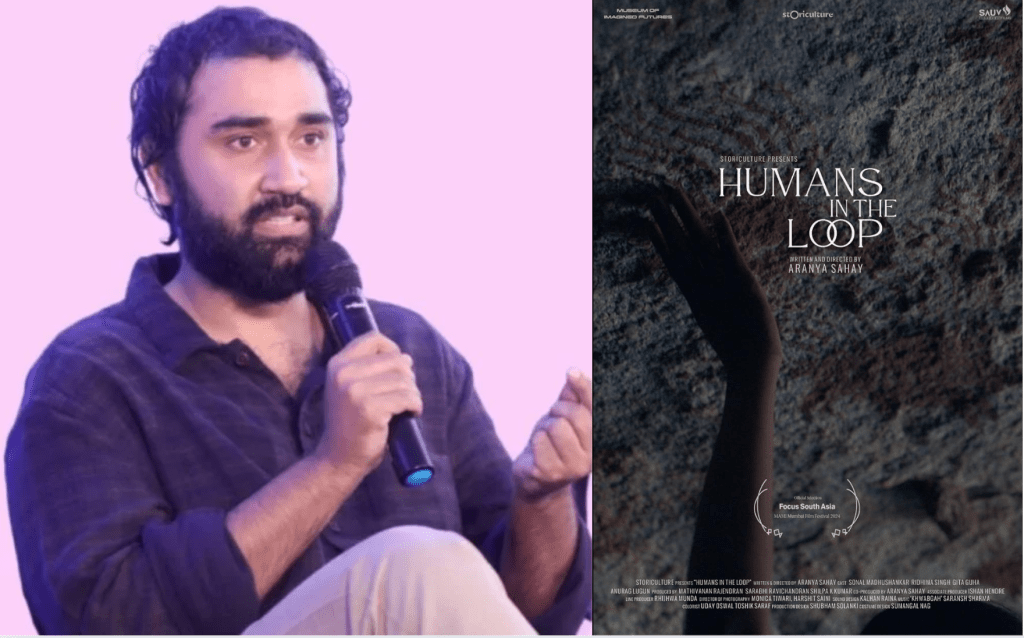

“Could We See AI as a Child?”: Aranya Sahay on His Debut Film, Humans in the Loop

In Aranya Sahay’s gentle, meditative debut feature Humans In The Loop, training an AI is deftly contrasted against raising a child. Input the right data into one, and it’ll give you the right answers; with the other, however, you can’t help but feel like you’re getting it all wrong.

Oraon tribal woman Nehma (Sonal Madhushankar) finds this out the hard way, having moved back to her ancestral village in Jharkhand after separating from her husband Ritesh (Vikas Gupta). To secure custody of their young daughter, Dhaanu (Ridhima Singh), and infant son, Guntu, she begins working at a data labeling centre, training AI for an American tech firm.

Sahay juxtaposes Jharkhand’s sun-dappled fields and fog-shrouded hills against the artifice of what’s onscreen, work punctuated by clicks and typing. But that’s not the only radical change in the environment Nehma must contend with. In one scene, she’s directed to label caterpillars as pests so that an AI-powered farming machine can target and destroy them. Instead, she refuses, knowing that since caterpillars only eat away at the rotting parts of a plant, they’re actually salvaging it. The tech firm doesn’t care for Nehma’s insight, only her ability to follow instructions. They complain of faulty and mislabeled data, and she’s eventually berated.

Humans In The Loop critiques how international tech companies rely on indigenous labor while suppressing marginalized voices. To build up artificial intelligence, Nehma must shrink her own. To programme a robot, she must think robotically too. Even new technology is gradually tainted by ingrained stereotypes and prejudices. When Nehma’s supervisor looks up photos of AI-generated tribal women, based on data she was working on, it still envisions her as fair-skinned with light hair. It used her input, but erased her presence.

If Nehma’s voice is silenced at work, her daughter’s isn’t heard at home. Dhaanu is shunned at school and is having a hard time adjusting to village life, but Nehma assumes she’s parroting Ritesh’s words, refusing to believe her complaints are borne out of her own experiences. With a delicate hand, Sahay examines the difficulties of nurturing, whether an AI or a child.

A Mumbai-based filmmaker, he’d wanted to center Adivasi stories since his days at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 2018. The longform 2022 Fifty Two article, “Human Touch,” had him hooked with the picture it conjured from the outset: A tribal woman begins interacting with AI. Unlike Nehma, the women interviewed for the piece were largely uninterested in the impact of their work, instead focusing on how the dull, repetitive task of labelling had helped them escape otherwise stifling lives involving patriarchal families or abusive husbands.

What made its way into the film was how their work was often invisibilized. To understand Jharkhand’s culture better, Sahay moved to the state for a year in 2023, simultaneously continuing to research AI models.

Humans in the Loop premiered at the 2024 MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and later screened at the International Film Festival Kerala. Sahay, who shot the film in 12 days, spoke about his novel approach to AI and the fallibilities of tech. What follows is an edited excerpt of my conversation with him.

Gayle Sequeira: What about the article on Fifty Two struck you and made you realize its cinematic potential?

Aranya Sahay: The fact that this work was happening in Jharkhand really struck me. I wanted to explore what it meant to come from an indigenous background and begin interacting with the technology of the future. My mother is a sociologist and wrote her thesis on indigenous communities in North-East India. When she was researching, she was pregnant with me. The tribals had even given me a name, Lalsiyama, which is now my middle name.

I realized the job of data labeling—in which, for example, a human being labels a chair and a table so the algorithm recognizes the difference between them—mirrors the act of parenting. When our children are growing up, we teach them to differentiate between colors and objects. We force our morality onto them. Could we then see AI like a child? That let me explore a plethora of ideas. So the premise of Humans in the Loop became: an Adivasi mother tries to raise an AI child. The conflict is that she’s having to raise it primarily through first-world data. So the algorithm will never see the world through her eyes.

GS: Your approach to AI is novel. Tell me about framing it not as a looming threat, but as a child that you can mould.

AS: Most films draw a doomsday parallel; they look at the consequences of AI. None of them are really looking at AI’s development, its origins, what forms an algorithm, or what biases might seep into an algorithm. The question then is: are we at a place where we can change it and make AI a significant ally? Or are we past that? I’d like to believe we’re on the cusp of that. AI could actually be an asset to humanity and can solve many problems.

But at the same time, it’s being used in warfare, policing, governance, and is controlled by business interests. I wanted to explore how an algorithm learns to differentiate between various things and what the implications of those are. Tomorrow, if an algorithm has to identify a criminal, it will have been trained on biased data because a lot of our policing and judgments have also been from a skewed lens—just take the Black community in the West, which has been disproportionately profiled.

What also stood out to me about data labeling was how we have been doing it since cave paintings—those have been the first markers of what animals exist in a particular area, for example. In Humans in the Loop, we jump from a cave painting to a CAPTCHA, which is also a kind of data labeling. It dawned on me: wow, we’ve been doing this for millennia.

GS: You’ve spoken about how, during your FTII days, you were inspired by a reporter covering Jharkhand’s mining politics, but at the same time, you weren’t clued into the state’s culture or environment enough. What was your research into the area like?

AS: Back then, I was going through a process of discovering how liberating a camera could be, and a reporter [covering mining politics] had spoken about the same thing. I wanted to explore an idea I had, but I didn’t understand Jharkhand at all. If I had to make a fiction film, then I would’ve had to shoot it in Pune with only a bit of knowledge about Jharkhand, so I didn’t even attempt it. I went to the state in January 2023. I reached out to Adivasi filmmakers because filmmakers open up the world in an authentic way—it’s not pure nuts and bolts, facts and figures. It’s not jaded.

These filmmakers really held my hand through the process. They helped me connect with writers, Adivasi art conversationists, and singers. I met bureaucrats, academicians, journalists, and data labelers.

GS: How did those interactions shape Humans in the Loop?

AS: Much of the film’s philosophy comes from my interactions with Adivasi women. Bulu Imam, one of the art conservationists that [filmmaker] Biju Toppo put me in touch with, had not only preserved cave paintings but had also discovered 70 Neolithic and Paleolithic rock art sites. I took the premise to his wife, Philomina, and we would talk about it for five or six hours at a stretch. Two conversations seeped into the film. She said, “When you walk on grass as a non-Adivasi person, then you think you’re entitled to it. There’s no connection between you and the grass. But when we walk on it, we thank it, and that’s the fundamental difference in the way we look at life.”

She also told me that an Adivasi child learns the ways of the jungle by age 12. But my question was: if there’s a child whose mother is indigenous, but she’s grown up in the city, would the ways of the jungle come back to her if she returned to the village? She said, “No, I don’t think that would happen.” But I wanted to explore it, so she gave me examples. She said there was a boy who’d studied in Delhi but had returned here with his mother, and in no time, he was able to identify things like plant roots.

GS: Tell me about your choice of an Adivasi woman as your protagonist. She’s ‘othered’ on two levels—Nehma’s voice is not only minimized by the Americans who don’t value her insight, but within her own community too, where Dhaanu is shunned by her classmates.

AS: With Dhaanu, I wanted to show how bias exists even in a community as progressive as an Adivasi community. There’s this ostracization of a child born from a Dhuku marriage [a kind of tribal marriage in which a couple begins living together without a formal ceremony]. You have to give your protagonist an emotional wound, right? So Nehma is being rejected by her husband and his family, but for Dhaanu, apart from her being forced to move to the village, it’s also that she’s ostracized. I could then draw parallels between the bias against Dhaanu and the bias Nehma faces at work.

Data labeling companies ensure they hire marginalized women because there is an aspect of meeting quotas, and it looks like a nice thing to do on paper. But women are also shamed for working. A woman takes up a job, but also has to cater to her family and in-laws. That idea made its way into the film. Nehma leaves the house, and her husband guilt-trips her because of it.

GS: You also point out how fallible tech is, through the scenes of GPS getting Dhaanu lost in the forest, or the stereotypes that AI propagates.

AS: If you look at the earliest Google AI algorithms, you’ll see their fallibility. For example, Google had developed an algorithm for recruitment. It inadvertently began to recruit only men, because the 10 years of data it had been trained on were mainly the CVs of male candidates. So it’s an ever-evolving entity, and it needs to be course-corrected. Humans will always be in the loop. Otherwise, it will depict the hegemonic systems that seep into it.

In Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel Dune (1965), all thinking machines are banned, and so humans have to enlarge their own potential—in navigation, mathematics, and computing. So they begin to develop certain abilities. Some folks become mentats [people who can organize and calculate vast amounts of data], some become guild navigators [clairvoyants who can plot safe routes through interstellar and intergalactic space]. There’s something so strong about human ability—when I had to trek through Jharkhand’s jungles, my ability to navigate them got better each day. The map would just not work.

There was this idea of human potential vs our excessive reliance on technology, and whether human potential could be enhanced via our interactions with the natural world. So when Dhaanu gets lost, a porcupine shows her the way out. In the last shot, when she comes back to the jungle, she lands in the right place. That happens because she’s remembered the path from when the porcupine led her out.

GS: Tell me about your visual approach to Humans in the Loop. There’s such a contrast between the lush landscapes and the artifice on the screens they’re working with.

AS: Everything came from the state of mind of the characters and the spaces they were inhabiting. Our visual approach was to segregate colours—so in the data-labeling space, even though the walls are green, the colours on-screen are very binary. The images are predominantly white. The square-ish 1.55:1 aspect ratio we chose enabled us to showcase not just the landscapes, but also the landscapes of the face, beautifully.

In Aranya Sahay’s gentle, meditative debut feature Humans In The Loop, training an AI is deftly contrasted against raising a child. Input the right data into one, and it’ll give you the right answers; with the other, however, you can’t help but feel like you’re getting it all wrong.

Oraon tribal woman Nehma (Sonal Madhushankar) finds this out the hard way, having moved back to her ancestral village in Jharkhand after separating from her husband Ritesh (Vikas Gupta). To secure custody of their young daughter, Dhaanu (Ridhima Singh), and infant son, Guntu, she begins working at a data labeling centre, training AI for an American tech firm.

Sahay juxtaposes Jharkhand’s sun-dappled fields and fog-shrouded hills against the artifice of what’s onscreen, work punctuated by clicks and typing. But that’s not the only radical change in the environment Nehma must contend with. In one scene, she’s directed to label caterpillars as pests so that an AI-powered farming machine can target and destroy them. Instead, she refuses, knowing that since caterpillars only eat away at the rotting parts of a plant, they’re actually salvaging it. The tech firm doesn’t care for Nehma’s insight, only her ability to follow instructions. They complain of faulty and mislabeled data, and she’s eventually berated.

Humans In The Loop critiques how international tech companies rely on indigenous labor while suppressing marginalized voices. To build up artificial intelligence, Nehma must shrink her own. To programme a robot, she must think robotically too. Even new technology is gradually tainted by ingrained stereotypes and prejudices. When Nehma’s supervisor looks up photos of AI-generated tribal women, based on data she was working on, it still envisions her as fair-skinned with light hair. It used her input, but erased her presence.

If Nehma’s voice is silenced at work, her daughter’s isn’t heard at home. Dhaanu is shunned at school and is having a hard time adjusting to village life, but Nehma assumes she’s parroting Ritesh’s words, refusing to believe her complaints are borne out of her own experiences. With a delicate hand, Sahay examines the difficulties of nurturing, whether an AI or a child.

A Mumbai-based filmmaker, he’d wanted to center Adivasi stories since his days at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in 2018. The longform 2022 Fifty Two article, “Human Touch,” had him hooked with the picture it conjured from the outset: A tribal woman begins interacting with AI. Unlike Nehma, the women interviewed for the piece were largely uninterested in the impact of their work, instead focusing on how the dull, repetitive task of labelling had helped them escape otherwise stifling lives involving patriarchal families or abusive husbands.

What made its way into the film was how their work was often invisibilized. To understand Jharkhand’s culture better, Sahay moved to the state for a year in 2023, simultaneously continuing to research AI models.

Humans in the Loop premiered at the 2024 MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and later screened at the International Film Festival Kerala. Sahay, who shot the film in 12 days, spoke about his novel approach to AI and the fallibilities of tech. What follows is an edited excerpt of my conversation with him.

Gayle Sequeira: What about the article on Fifty Two struck you and made you realize its cinematic potential?

Aranya Sahay: The fact that this work was happening in Jharkhand really struck me. I wanted to explore what it meant to come from an indigenous background and begin interacting with the technology of the future. My mother is a sociologist and wrote her thesis on indigenous communities in North-East India. When she was researching, she was pregnant with me. The tribals had even given me a name, Lalsiyama, which is now my middle name.

I realized the job of data labeling—in which, for example, a human being labels a chair and a table so the algorithm recognizes the difference between them—mirrors the act of parenting. When our children are growing up, we teach them to differentiate between colors and objects. We force our morality onto them. Could we then see AI like a child? That let me explore a plethora of ideas. So the premise of Humans in the Loop became: an Adivasi mother tries to raise an AI child. The conflict is that she’s having to raise it primarily through first-world data. So the algorithm will never see the world through her eyes.

GS: Your approach to AI is novel. Tell me about framing it not as a looming threat, but as a child that you can mould.

AS: Most films draw a doomsday parallel; they look at the consequences of AI. None of them are really looking at AI’s development, its origins, what forms an algorithm, or what biases might seep into an algorithm. The question then is: are we at a place where we can change it and make AI a significant ally? Or are we past that? I’d like to believe we’re on the cusp of that. AI could actually be an asset to humanity and can solve many problems.

But at the same time, it’s being used in warfare, policing, governance, and is controlled by business interests. I wanted to explore how an algorithm learns to differentiate between various things and what the implications of those are. Tomorrow, if an algorithm has to identify a criminal, it will have been trained on biased data because a lot of our policing and judgments have also been from a skewed lens—just take the Black community in the West, which has been disproportionately profiled.

What also stood out to me about data labeling was how we have been doing it since cave paintings—those have been the first markers of what animals exist in a particular area, for example. In Humans in the Loop, we jump from a cave painting to a CAPTCHA, which is also a kind of data labeling. It dawned on me: wow, we’ve been doing this for millennia.

GS: You’ve spoken about how, during your FTII days, you were inspired by a reporter covering Jharkhand’s mining politics, but at the same time, you weren’t clued into the state’s culture or environment enough. What was your research into the area like?

AS: Back then, I was going through a process of discovering how liberating a camera could be, and a reporter [covering mining politics] had spoken about the same thing. I wanted to explore an idea I had, but I didn’t understand Jharkhand at all. If I had to make a fiction film, then I would’ve had to shoot it in Pune with only a bit of knowledge about Jharkhand, so I didn’t even attempt it. I went to the state in January 2023. I reached out to Adivasi filmmakers because filmmakers open up the world in an authentic way—it’s not pure nuts and bolts, facts and figures. It’s not jaded.

These filmmakers really held my hand through the process. They helped me connect with writers, Adivasi art conversationists, and singers. I met bureaucrats, academicians, journalists, and data labelers.

GS: How did those interactions shape Humans in the Loop?

AS: Much of the film’s philosophy comes from my interactions with Adivasi women. Bulu Imam, one of the art conservationists that [filmmaker] Biju Toppo put me in touch with, had not only preserved cave paintings but had also discovered 70 Neolithic and Paleolithic rock art sites. I took the premise to his wife, Philomina, and we would talk about it for five or six hours at a stretch. Two conversations seeped into the film. She said, “When you walk on grass as a non-Adivasi person, then you think you’re entitled to it. There’s no connection between you and the grass. But when we walk on it, we thank it, and that’s the fundamental difference in the way we look at life.”

She also told me that an Adivasi child learns the ways of the jungle by age 12. But my question was: if there’s a child whose mother is indigenous, but she’s grown up in the city, would the ways of the jungle come back to her if she returned to the village? She said, “No, I don’t think that would happen.” But I wanted to explore it, so she gave me examples. She said there was a boy who’d studied in Delhi but had returned here with his mother, and in no time, he was able to identify things like plant roots.

GS: Tell me about your choice of an Adivasi woman as your protagonist. She’s ‘othered’ on two levels—Nehma’s voice is not only minimized by the Americans who don’t value her insight, but within her own community too, where Dhaanu is shunned by her classmates.

AS: With Dhaanu, I wanted to show how bias exists even in a community as progressive as an Adivasi community. There’s this ostracization of a child born from a Dhuku marriage [a kind of tribal marriage in which a couple begins living together without a formal ceremony]. You have to give your protagonist an emotional wound, right? So Nehma is being rejected by her husband and his family, but for Dhaanu, apart from her being forced to move to the village, it’s also that she’s ostracized. I could then draw parallels between the bias against Dhaanu and the bias Nehma faces at work.

Data labeling companies ensure they hire marginalized women because there is an aspect of meeting quotas, and it looks like a nice thing to do on paper. But women are also shamed for working. A woman takes up a job, but also has to cater to her family and in-laws. That idea made its way into the film. Nehma leaves the house, and her husband guilt-trips her because of it.

GS: You also point out how fallible tech is, through the scenes of GPS getting Dhaanu lost in the forest, or the stereotypes that AI propagates.

AS: If you look at the earliest Google AI algorithms, you’ll see their fallibility. For example, Google had developed an algorithm for recruitment. It inadvertently began to recruit only men, because the 10 years of data it had been trained on were mainly the CVs of male candidates. So it’s an ever-evolving entity, and it needs to be course-corrected. Humans will always be in the loop. Otherwise, it will depict the hegemonic systems that seep into it.

In Frank Herbert’s sci-fi novel Dune (1965), all thinking machines are banned, and so humans have to enlarge their own potential—in navigation, mathematics, and computing. So they begin to develop certain abilities. Some folks become mentats [people who can organize and calculate vast amounts of data], some become guild navigators [clairvoyants who can plot safe routes through interstellar and intergalactic space]. There’s something so strong about human ability—when I had to trek through Jharkhand’s jungles, my ability to navigate them got better each day. The map would just not work.

There was this idea of human potential vs our excessive reliance on technology, and whether human potential could be enhanced via our interactions with the natural world. So when Dhaanu gets lost, a porcupine shows her the way out. In the last shot, when she comes back to the jungle, she lands in the right place. That happens because she’s remembered the path from when the porcupine led her out.

GS: Tell me about your visual approach to Humans in the Loop. There’s such a contrast between the lush landscapes and the artifice on the screens they’re working with.

AS: Everything came from the state of mind of the characters and the spaces they were inhabiting. Our visual approach was to segregate colours—so in the data-labeling space, even though the walls are green, the colours on-screen are very binary. The images are predominantly white. The square-ish 1.55:1 aspect ratio we chose enabled us to showcase not just the landscapes, but also the landscapes of the face, beautifully.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.