Billionaires are being produced at the same time that people are actually dying from lack of food – A conversation with Balmurli Natrajan

As the world’s largest democracy goes to the polls with 900 million voters getting ready to decide the future of the Republic, The Polis Project is speaking to scholars, writers, artists and activists about some of the most critical issues affecting India today. In this Podcast, Suchitra Vijayan speaks to Prof Balmurli Natrajan about the political and cultural history of Hindutva, it’s a relationship to fascism, how caste and violence are deployed by Hindutva and what awaits the country in the aftermath of the elections.

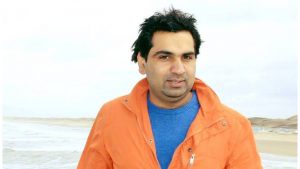

Balmurli Natrajan is Professor of Anthropology at William Paterson University of New Jersey, USA. An anthropologist and engineer by training, Murli’s research and teaching interests are on caste, class and gender, globalization & development, and nationalism and fascism. He has published in scholarly journals, books, and in popular media. His books include Culturalization of Caste in India: Identity and Inequality in a Multicultural Age based on artisanal labor and caste, and a co-edited volume with Paul Greenough Against Stigma: Studies in Caste, Race and Justice Since Durban. Recently he co-authored a study on food habits and politics in India, which demolished many myths about vegetarianism and beef eating. His popular writing has been on Hindutva, Hinduism, vigilante culture, and myths about caste. His current research is on explanations of toilet behaviour (Chhattisgarh, India), and collectivization of domestic workers (Bengaluru, India). Murli has also been active in solidarity work around South Asia in the USA focusing on issues of secularism, human rights, and neoliberalism.

The text has been edited for style and clarity.

Suchitra Vijayan: We keep hearing the word ‘Hindutva’ often. It has become normalized in the last four or five years. But before we go into the question of elections, can you tell us what Hindutva is and place it in the broader context of India’s history? Hindutva was not a recent phenomenon, it’s been ongoing for a long time.

Balmurli Natrajan: You’re right. Glad you’re starting it off not with the elections because Hindutva goes far beyond electoral politics. Hindutva, I believe, is a form of ethnoultra-nationalism that is transforming very very quickly into what Thomas Blom Hansen, an anthropologist who studied Hindutva, calls “Swadeshi fascism” and the way it does that is through a mode of authoritative populism. These are all big names, so let’s kind of unpack it. The way I thought we could do it is by taking an example. By now everybody has heard of the “cow vigilantes” or the “gau rakshaks” and, over the last several years, especially over the last about six or eight years, a number of cow vigilante groups roam around the countryside and attack people, intimidate, threaten and from time to time lynch, or kill people in public, and some of those videos go viral, and you have a large number of people watching. In fact, many times the cow vigilantes themselves use police jeeps, and the police themselves are by and large mute spectators by many accounts. By many accounts, and I know that your group has also done some work on this, about 95% of these attacks have come after 2014, which was when the current political regime came into power.

Here are some of the things that we now know for sure. Almost all of the cow vigilantes are either members of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) the World Hindu Council, or its paramilitary affiliate the Bajrang Dal, which translates roughly to Strong Squad, or any number of other smaller affiliates. Almost all of them have, in one way or another, been associated with this. Let’s actually take the BJP, the Bharatiya Janata Party which is the Indian ruling political party. Prime Minister Modi took about 11 months before he made a very muted statement after the first Muslim person was lynched. His name was Mohammed Akhlaq. It took another year for the prime minister to actually make another statement, and this time only after a very huge protest movement under the hashtag #NotinMyName came about. We ought not to also be surprised that Prime Minister Modi in the electoral campaigns of 2014 actually enabled some of this by using the word “गुलाबी क्रांति” which translates to Pink Revolution, pink referring to the colour of meat, and very clearly talking about cow slaughter and eating of beef. We also shouldn’t forget that this has had a long history. Even in the late 19th century onwards there have been serious movements around rallying around the cow. Let’s actually take a couple of more events.

In September 2017 the Supreme Court here took a bold move and condemned cow vigilantes and ordered the centre as well as state governments to get adequate compensation and to find a way to stop the killings. A few days after the Supreme Court ruling, the Sarsanghchalak or the supreme leader of the RSS, which stands for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh which translates to National Service Corps, said the following. He said, “cow protectors and promoters who are piously involved in the activity should not worry or get distracted with well-intentioned statements by highly placed persons in the government or remarks made by the Supreme Court.” So here you have a set of organisations, the VHP, the Bajarang Dal, the BJP, the RSS and their affiliates. All of them seem to have made some kind of an attempt to either enable or to erase or to pretend that cow vigilantism doesn’t exist, or to actively strongly encourage and to actually participate as cow vigilantes themselves.

What if each of these organisations were actually part of a more extensive network? And indeed, we see that they are. And this network therefore then needs to be recognized for what it is. The name of this network is the Sangh Parivar or the “Collective Family”. The Sangh Parivar is then made up of the RSS as it’s ideological and muscular fountainhead. RSS started off in 1925, so it’s close to a hundred years. It then has the Vishnu Hindu Parishad which is from 1964 I believe, and that’s the religious and ideological part of the organisation. The Bajrang Dal from 1984 is the lumpen paramilitary element which is very much part of it, and then the BJP which actually comes into existence only in 1980 but has an earlier form of existence in the 1950s as the Jana Sangh. Along with these, there are numerous other affiliates and here are three or four functions they fill for the Sangh Parivar. The Sangh Parivar is, then, ideological and organisational condensation of Hinduvta. All these organizations, the big four or five and a number of others, they also end up organizing students and labour. For example, they also have a variety of other paramilitary organizations and most recently a cache of arms in 2006 was found and linked to an organization called Abhinav Bharat which is linked to a series of bomb blasts and terror outfits.

You also have a large-scale network of humanitarian organisations linked to the Sangh Parivar that actually do development work, especially relief work, under humanitarian aid camouflaged in a way. And, they also have an extensive network of educational, media, and cultural communicational organisations. So, media houses, printing presses, a wide range of dissemination of culture. What does all this mean then? The reason I have insisted on laying it out in this kind of a way is because Hindutva, how it operates through the Sangh Parivar and its affiliates, is really part of a larger public culture of India. And this has been in the formation for at least a century, maybe a little bit more. In characterising what Hindutva is and what it means, its implications for us today and therefore what we can do, we need to understand that it’s very clearly not simply the capture of electoral power, which is right now happening through the BJP. There’s a revolving door with all kind of personnel who are part of the RSS, are also heading the VHP, they’re also very much heading the BJP with all its functionaries at the top having some RSS dyed in the wool colour. And for a long time, these linkages in the network was denied, but today it is boldly emphasised and very clear for anyone to see.

So let’s now take Hindutva as an ideology. If you take two of its founding texts, one is by Savarkar, the founders of Hindutva along with the supreme leader, his name was Golwalkar, known as Guruji. He wrote the book Bunch of Thoughts and Savarkar’s book titled [Essentials of] Hindutva. Between these two, the core ideology of Hindutva comes out to be some form of ethnonationalism. By this, we mean that, and to take their own terms, “Hindu, Hindi and Hindustan.” This is the core motto. When we hear the word Hindu we tend to think of religion, but interestingly, and I don’t know how many people know about this, but those who follow the Sangh’s activities know it very clearly. The founders of the Sangh were non-believers, they were atheists. So when they speak of the word Hindu it’s really not a restrictive religious identity. It’s actually a racial identity. Hindu, in a sense as a racial stock, and they go back to very dubious theories of origins, autochthonous theories of the origin of Hindus as Aryans and things like that. The linguistic identity of Hindi is a hegemonic identity.

SV: When you say the Hindu identity is racial, what does it exclude?

BN: For Hindutva, the Hindu identity is racial. So it seeks to exclude those who they see as not part of the territory. That’s the third aspect, so Hindu, Hindi, and Hindustan. Hindustan is a territorial aspect. Who are then not original to the land of Hindus are the racial other. And this comes down basically to Muslims and Christians. In fact, the racialisation also is looked at in this way.

Who’s a Hindu? Well, for Hindutva at least, for its founding and core ideology, everybody in India is a Hindu, and this means anyone who is a Muslim has actually converted, and they have a way in which to convert them back, that’s the way of making them belong. Now Hindi then is a language of one part of the population of India. It’s one language within one of the larger language families of India. But the idea is to kind of make it stand for the whole. So that’s where you get the ethnic identity, the cultural identity. So the mixing then of race, culture, language and territory – this makes the core of Hindutva ideology. Christophe Jaffrelot, who is a very widely published student of Hindutva, calls this ‘ethnonationalism’. I prefer the term, as a start, as ‘ethnoultra-nationalism’. The difference is that Hindutva doesn’t just connote majoritarian nationalism. It demands from everybody, who is on that soil, to actually transform or be forever subjugated as a second or third class citizen or be done away with.

But even ethnoultra-nationalism is not really enough to capture it. Let me say a little bit about another founding text. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) had a 40-point Hindu agenda in 1998. I’m just quoting the first point, “Hindutva is synonymous with nationality, and Hindu society is indisputably the mainstream of Bharat [this is the name that Hindutva prefers for India]. Hindu interest is the national interest. Hence the honour of Hindutva and Hindu interests should be protected at all costs.” This is in short an ideology of Hindu supremacy clothed as nationalism, for as you see, then an ethnic and a racialised category that flows very clearly into Savarkar’s and Golwalkar’s ideas. I feel that even calling this ethnoultra-nationalism is not enough. And we need actually to look at some of the other contesting terms.

Along with ethnonationalism, the other term is fascism. A lot of scholars use that, it’s not something people can just brush away as being alarmist. There are scholarly tomes looking not just at fascism but looking at Hindutva as fascism. Let me then make a little bit of an inroad in there. Thomas Blom Hansen introduces the word “swadeshi fascism” but he actually steers away from there, and he prefers to call Hindutva as a ‘conservative revolution’. I want to see how, for example, this kind of ethnoultra nationalism transforms to swadeshi fascism. For that, we have to give up an idea of fascism being either linked to Mussolini, or to Hitler. These are but the most recent forms that fascism took in Europe. But fascism as a mass phenomenon, as a cultural phenomenon, starts off in the late 19th century.

Like Arthur Rosenberg, who was a teacher actually in Brooklyn and for a very long time, also a student of fascism. Using some of his writings, I think there are five core elements of Hindutva, which allows us to see how it is closer to fascism. The first one, of course, is some form of ethnoultra-nationalism. But it’s also important for us to ask the question why did it come to be and how does it sustain itself. So one of the core elements of Hindutva is a staunch anti-liberalism. Anything that has something to do with the broad philosophy of liberalism that has kind of been with us in a very cogent way since the French Revolution, and when I say ‘us’ it means humanity. But a staunch anti-liberalism is very much part of the mass culture of Hindutva which is a fascistic culture. The third point is that it is very clearly counter-revolutionary capital. This, of course, means that there is some form of a revolutionary capitalist, and maybe its time is gone, but compared to what it was setting out to destroy, there were certain parts of capitalism that we could think of as revolutionary.

But counter-revolutionary capital is a very clear project of entrenchment of neoliberal policies and very clearly anti-labour, heaped with contempt and banishing them into what I would now say as a fourth core, which is some form of demagogic national renewal. Hindutva constantly needs to talk about the nation in need of being renewed. A new India, a new Bharat, a new Hindu, a new everything from their point of view to be renewed, and therefore it constantly creates ‘enemies’. Actual bodies are deemed to be capable of being a threat and seen as ‘enemies’. All of these bodies are political dissidents, but there’s a difference. I would say that Muslim and Christian bodies are racialised although they appear to be simply religious. They’re also racialised. Those bodies along with left secular rationalist public intellectuals or any civil liberties human rights activists that we increasingly see today, these are bodies that can be disposed of, that can be excised. That kind of difference will not be tolerated. On the other hand, Dalits, Adivasis, women, sexual minorities, students, and youth, all of these are also folks who don’t quite fit into a Hindutva ideology. But Hindutva can’t afford to get rid of them completely. There would be nobody else left. And in that sense, they start to get domesticated, disciplined, kept in place, from time to time repressed in significant ways, but not sought to be totally eliminated with caste.

SV: Can you lay out Hindutva as a part of a larger continuum of fascism, in relationship to caste, and also how violence, then, plays out as a kind of disciplining force?

BN: Before I get into that, let me just remind ourselves that, and the word is communalism, so in the Indian context or the South Asian context, communalism refers to some kind of religious communitarian conflicts. But here is where Nehru had famously quoted in the 1930s or 40s, I forget, and the quote is, “Muslim communalism cannot dominate Indian society and introduce fascism. That, only Hindu communalism can do.” Let’s actually think about the cow vigilantes again. The fifth core of Hindutva, followed by ethnoultra-nationalism, along with the anti-liberalism, counter-revolutionary capitalism, and constant national renewal, is the storm-trooper like methods. There are stormtroopers roaming around with the full impunity that they are able to get because nothing seemingly seems to be done against them. Three years ago four Dalit youth who were stripped and beaten for about four hours in public. Again this is part of the gau rakshak or the cow vigilantes. Interestingly, about a month after that the prime minister said that nobody should beat my Dalit brothers, they should beat me instead.

So I want to just place this out there as to what we think about what Dalit and caste mean to Hindutva. Hindutva has a significant problem on its hands. It is now very clearly seen that it is anti-Constitutional. I think 1998 manifesto of the BJP was very clear that it wants to make radical changes to India’s constitution. Dalits hold the Constitution very dear. Everybody should hold the Constitutional very dear. It is probably the single document that prevents India from even more quickly transforming into a fascist society and state. In a way, Ambedkar, who was one of the chief drafters of the Constitution, said, I can only paraphrase, but he said that in a way the political equality that the Constitution talks about is based on social and economic inequality. It’s like building a house on a dung heap and it will be blown apart by rising masses, in a sense, if things weren’t taken care of. Many decades later we are still, actually, we are worse off in some sense.

Anti-Constitution is a big way in which Dalits view Hindutva increasingly. The ban on cow slaughter has impacted huge numbers of farmers who all depend on selling their decrepit cows at the end of whatever ten or fifteen years, then they’re not able to sell it so this has impacted farmers who are out in a very massive way in protest against the present regime. But it has also affected the leather industry in which many Dalits are employed. At the same time Una, which is the place in Gujarat where the four Dalit youth were flogged in public by the cow vigilantes, showed what Dalits are capable of when they rise up with a very clear cut understanding of what they’re facing. There was a way in which many of the Dalits, who were forced to through the caste system carry the dead bodies of cows and to skin them, they went back and threw the dead bodies in public and refused to pick them up and said from then on they would not do their traditional work. And this was a very big moment in caste resistance where you see how the ‘normal’ workings of caste could not go on anymore.

The beef festivals, the open beef festivals that are being held in India by many youth on campuses led by Dalits, but also with large participation of a number of others, that’s another way in which the Dalits are rising up. Most recently, there is the Bhima Koregaon case, slightly more than a year ago. There’s a cultural celebration of a battle in the 19th century done by Dalits, and the government has come down very harshly on all the celebrations and started attacking Dalits and putting more than 200 Dalits in some way, arrested as being anti-nationalists. So to kind of sum some of these things up, Hindutva is at its core casteist, Brahmanical and patriarchal. I want also to emphasize that intersectionality – that it needs to discipline women and men because it is operating from a kind of a mysophobic culture. In the studies of the ‘new right’ in France, for example, there’s a way in which we learn that multiculturalism can very much be viewed as a good thing by the right wing.

How is that so? Part of that is because we tend to think of ‘heterophobia’ as the main metaphor by which bigotry takes place, but there’s also ‘heterophilia’. I would actually like you for your difference, just don’t marry my daughter. Keep your culture to yourself, and in that sense, heterophilia also operates and include things like honour killings (I don’t like that term at all. There’s honour in killing?). But the victims are entirely almost Dalits. Dalit men, or Dalit women, and occasionally the people that they fall in love with. Along with this cow vigilantism many other cultural rituals have been invented by Hindutva. And one of them is ‘love jihad’, they are the vigilante groups that go around, and anybody who is having any kind of an inter-caste or inter-religious relationship is pounced upon. And it seems that the boundaries of caste and religion have to be protected on the bodies of young boys and girls. There’s another thing called ghar vapsi meaning coming back home. This operates through the racial imagination of Hindutva wherein anybody who is a Muslim or a Christian, and many of the Adivasis in India are having indigenous religions or have converted to Christianity especially, but also Islam, they are sought to be reconverted because it is assumed that anyone here is racially a Hindu in that sense. And when they’re doing this most of the conversions are actually of either low caste or Dalit people, who may have converted many years ago. So one can’t think of Christians only being converted, they’re mostly Dalits too. So caste is everywhere in these kinds of things.

The National Crime Records Bureau, for example, says that between 2013-2015 there was 176% rise in crimes against Dalits. Now, this goes under the Anti-Atrocity Act [The Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989]. The ruling regime has tried to very clearly dilute the Anti-Atrocity Act. That’s another anti-Dalit thing. They’ve also done – in some really absurd ways – they’re against the reservations, which is the Indian equal of affirmative action, without which we would not be seeing even the few Dalits or Adivasis that we see in universities as students as well as faculty. They have definitely tried to make a mockery of that. So there are also a number of ways in which the anti-labour legislations are on the plate. Every labour legislation, be it with minimum wages or under the Factory Act, or the right to unionise, all of that are actually systemically being broken down and, Dalits face the brunt of it. You must remember that most of India’s Dalits are overwhelmingly landless, factory workers if they have a job, but they’re mostly in the informal sector.

SV: You have studied Hindutva for a very long time, would you say that there’s a sudden infatuation to this idea of Hindutva that has spread throughout the country, or, is it something that has always been in the works. You hear this word called the ‘bhakt’ which is the equivalent of saying someone who blindly follows Modi or the BJP, or the RSS, or the entire Sangh family. Do you see this as mass hysteria in the last few years? Why is there a sudden, public outpouring of this great love for the Dear Leader?

BN: Wow, fascinating question. Multiculturalism is cool, right, I don’t want to lay the blame on multiculturalism, but, I always laugh when I hear some of India’s leaders, even some who you think are a little more erudite, when they say, India is a very diverse society, look at the number of castes we have. Well, caste should not be celebrated and glorified as adding to our diversity. One should be very clear, caste is a form of violence. It is a form of structural violence. Why do Indians flirt at the very least or embrace this idea of Hindutva totally? We need to understand that you don’t have to be part of the BJP or the RSS or the VHP actually to believe in Hindutva. This is the tragedy, but also entirely an opportunity for those of us who will be struggling against it. Some ordinary people, they may be bureaucrats, they may be teachers, they may be your colleagues or bosses, they may be just about anybody with no party affiliation and they actually have a certain sense of some of the core tenets of Hindutva. They may not articulate it as such.

B.S. Moonje, From The Hindu Archives

What has happened then, is this kind of a build up. I think we are seeing this in dramatic ways, partly because of the proliferation of social media, mediated forms of information bombardment in a sense. But it’s been building up. Make no mistake, nobody has worked as hard as the Hindutva brigade, in a way, as the Sangh Parivar from day one. They have learned from the left on how to unionise, and they have their own unions, right to unions. They learned from the Christians on also how to do congregational work. They have learned from just about everybody. Their early students, there was a person called Dr Moonje, I don’t know what he was a doctor of, but he was in—I mean he actually travelled and met Mussolini, and for two decades in Maharashtra there were publications that talked very positively about fascism and Nazism. He went, and he wanted to learn about the youth organisation, the Balilla and the Avanguardisti in Italy. And so this has been going on for a while. Maharashtra has been a cauldron, but it’s no longer restricted to Maharashtra.

The idea of Hindu and the idea of Hindutva ought to be kept separate, for anybody struggling against Hindutva. However, Hindutva has by and large succeeded in equating the two. It actually depends on this – and I do want to throw that in the mix – that what is happening is that ordinary gurus, people who head sampradayas, mutts – I consider myself a student of Hinduism too. I actually grew up in a devout family, still do, and I’m a non-believer. But one cannot be a non-believer in these ethnicized times, one can say. And one has to understand the role that people, who are heading these religious units, play. They are clearly articulating an exclusionary form of a view of India, and the scapegoating has reached its kind of crescendo, where I think Jaffrelot has very clearly said that India is already probably like Israel, it’s an ethnic democracy, where you have a significant population that is condemned to perpetual second classness. And, I think it’s even worse, but that’s some of the attraction of it.

Nationalism, one could probably say, is the last part of authoritative populism. Authoritative populism is the mode by which swadeshi fascism comes to be, Hindutva comes to be swadeshi fascism. And what populism does is that it constantly creates a ‘frontier’. It creates a boundary in a population and says this is the ‘people’ and those are the ‘enemies’. So that boundary has been very clearly done time and time and time again in everyday practices of saying who’s the other, who’s the less than human, so sharing of food, showing any form of compassion whatsoever to the poor, but also to somebody else may be in the same class but from a different religion, is now seen as a zero-sum game. So in that sense, it’s time to take back a sense of what it means to be a Hindu. And I have a feeling that anybody who believes in any religion is fighting this fight. Muslims have to take back a sense of who is a Muslim from the political Islamists, or the jihadists, Christians have to take that back from the tea party or Christian fundamentalists or the Aryan nationalists/white supremacists, Jewish folks have to take it back from the hardcore Zionists and whoever else. So this is in a way the burden that anyone, who is a believer, carries.

But I believe it’s also a burden of secular non-believers like me to constantly say that we have to keep the distinction between Hindu and Hindutva clear as an indeterminate, always intentioned, be vigilant about it and not give in. Because that’s what Hindutva wants to speak for all Hindus, but they’re not able to do that easily, so they constantly have to keep these kinds of things coming out.

SV- Now that we have laid out both the history and the cultural phenomenon of Hindutva, I want to come to the big elephant in the room. Modi, and the rise of Modi, and what Modi has meant for India in the last four years. Can you break it down for us?

BM: A brief note on the Indian media, recently one of the best newscasters in India, Ravish Kumar, actually asked people not to listen to any media in this month, or two months, and I think most of the mainstream Indian media has capitulated. There are notable exceptions; anyone who wants to get some sober analysis and things like that has to depend on alternative media, non-corporate media and social media. And so there is thankfully a bunch of intrepid guerilla media folks who have come, and this includes people on Twitter, this includes people who are stand-up comedians, and we learn a lot from this kind of digital non-corporate media. And that kind of digital non-corporate media has put out regular report cards on the Modi regime. It doesn’t exist? It exists. Do people see it? Probably an increasing number are seeing it. Here is what is happening in the last four years, and this gets to hopefully a deeper understanding of why we are in the time that we are.

This is a historic time. India officially liberalised its economy in 1991. We are now in the third decade of that. The first decade was the only decade that saw not only a rise in the GDP, steady growth in the GDP but also some form of enjoyment of its benefits by a vast mass of people. New jobs were created, employment rose, wages rose to some extent. There was some promising note in that. This was also interestingly the time when the Indian state, this is the earlier, UPA 1 government, where many welfare rights were actually put in law. So you had the very famous NREGA, or the largest employment guarantee scheme in the world. And that was put into place then. There were a slew of other rights including Forests Rights Act, the PESA [Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996], for example, which allowed indigenous populations in India, the Adivasis, to actually have some kind of local community level control over the land that they had for very long, many generations. You had even the Right to Information Act, the Right to Education, a bunch of other things— broadly progressive acts, I would say with some form of welfare, security, food security, all kinds of things.

The next two decades saw the stagnation, for example, of the Indian economy, and in the last five years, which is of this regime, we’ve actually seen a crisis. This is an economic crisis. Most recently, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy actually placed India’s cumulative growth rate at about 1%. About 80-90% of India’s economy is in the informal sector, and that suffered a devastating decline, in large part due to the policy called the demonetization policy, which overnight, without even his finance minister knowing it, it was pushed through against all kinds of logic by top economists, including the Reserve Bank of India which is India’s central bank, and the chief of that. And contrary to the PR machinery, which is very huge in India for the ruling party, contrary to all their attempts to show it in a good light, there is nobody who is an economist of any worth who has anything good to say about it. Farmers are devastated, the small and medium scale industry, which is largely in the informal sector was totally devastated, traders lost things, all kinds of things happened, ok. So that is one thing which has kind of propelled a crisis.

The unemployment has actually grown in leaps and bounds, and both these things are very contrary and in stark contrast to the promises of the campaign in 2014, which brought absolute majority for the ruling party. So, they are having a hard time saying then that accepting that they’ve failed. But they’ve totally failed in generating employment, and in actually generating growth. Neither is the economy doing badly, nor-I mean, the economy is doing, and the people are also doing badly. At the same time, you have an incredible number of corruption charges that have now come out in the open light. No longer can the BJP say that it is the Congress that is corrupt. It’s actually beating them at their own game, and it’s actually beaten them in considerable ways because all the money after the demonetization is, largely in the hands of only one party today. If you look at the statistics thrown out by the electoral bonds, which is a new gimmick that was floated, about 80-90% of all the bonds are going to the BJP. What this then means is that billionaires are being produced at the same time that people are actually dying from lack of food. There is food insecurity, and at the same time, you have significant capital, crony capitalism, about 1% of India according to an Oxfam report that came out recently, about 1% of India owns about 70% of its wealth. It was always somewhere around 50%, but there’s been a jump too. And this is just in the last few years.

There’s an environmental crisis on top of it. Very recently, again in crony capitalist style, about 170,000 hectares, if I have my figures right, was just gifted away for open cast coal mining in Chhattisgarh, where I also do some work. And, there is a continuity with the previous government, and I want to emphasise that, and yet there is also a very clear rapaciousness that has really brought about an economic and environmental crisis. There is also a political crisis. The BJP has tasted absolute power, in a sense. So it constantly talks about wiping out the opposition. Not any kind of political engagement, it doesn’t want a coalition. It talks about making India Congress mukt. It actually has enough money to buy every politician out there. So if you see some politician who is not being bought, you must know that they have turned away a lot of money. I want to make it very clear— and these are not my words – but these are words from BJP politicians who on and off talk about the possibility that there may not be any more elections.

This comes from people holding some kind of an office, elected officials, or otherwise in the BJP. In their track record, for example, in Gujarat, and a bunch of other places where they’ve ruled for a very long time, it’s very common for them not to have any panchayat elections, for years on end. The Lok Pal elections were never held. So there’s a way in which politically also we’ve come to some kind of crisis. Can you have multi-party, democracy when you have one single party seeking to eliminate, wipe out, annihilate, anything else? And then there is, of course, this kind of cultural crisis. I’ve heard too many people who have long lived in India and fought every kind of repression. But they are all saying “well now we’re really afraid.” Electoral battle happening in a months time is critical for the very idea of India. These are stalwarts who’ve actually faced, hardcore oppression and they are in a way seeing these times as perilous times.

SV: I just want to discuss this idea of “this battle for India”. Just a week ago, one of India’s foremost constitutional lawyer, Menaka Guruswamy said that in this election if the BJP comes back to power, it’s the difference being a constitutional democracy, and it will cease being a constitutional democracy. And what happens if you lose the battle?

BM: Yes. These are dangerous times, no doubt. In 2014 the BJP came to power, not on the Hindutva agenda, which was always there, but they didn’t have to bring it out. They came largely on a developmental agenda. That developmental agenda is now dead. There is no segment of the population that is not on the streets. Students are on the streets, youth are on the streets, labourers are on the streets, women are on the streets, ethnic minorities are on the streets, all religious minorities are on the streets, the Dalits are on the streets, Adivasis on the streets. You name it, and they’re protesting something or the other. Things haven’t worked out. It’s a massive failure. So, this time, the elections are therefore not on the developmental agenda anymore. It’s also not on the anti-corruption agenda because the BJP has shown to be just as corrupt, if not worse. The agenda then is on hyper-nationalism, ultra-nationalism.

The Indo-Pak War that’s playing out in a big way, possibilities of that, and stories that are made of what to make of the muscle power of the BJP and how it can save India, that’s coming out in a big way. Ayodhya is coming out in a big way, this is a very clear battle for a symbolic victory for Hindutva, and they’ve been bringing it to the fore. This thing of branding anyone and everyone who is a political dissident as an anti-national that reached epic proportions, and I think the Bhima Koregaon case is the foremost symbol of that, but not just restricted to it, there are lots of others who are all being branded anti-national. The BJP has been very clear, in its 1998 manifesto, that it wants to make radical changes to the constitution. Our, constitution has enshrined in many ways and over different periods, an idea of secularism, as badly implemented as it is, it’s important to have that kind of a commitment in the single most important text on which our nation is built. It’s also had the commitment to socialism, and both of these are very clearly hated by the BJP and they want to tear it down in many ways. In some senses, everything depends on how and if the BJP comes to power.

For example, if it comes to power with an absolute majority, I would agree then with Menaka Guruswamy’s statement that constitutionalism would probably be the first victim. If it doesn’t come to power on an absolute majority but comes to power having to cobble together a bunch of other things, then it depends on how the coalition partners rein in the BJP. But regardless, if we are of the opinion that Hindutva is a 100-year mass public culture phenomenon, it sooner or later is going to get some sense of being very much in the hold of making its dream come true; of making India into a Hindu Rashtra. So I think the idea then is how do the rest of the population come together in a clear, common minimum program of being anti-Hindutva by understanding what Hindutva means? It’s not just being anti-BJP. I believe, Dalits, the Adivasis, all other kinds of minorities, and the left, and I mean not just the left parties, I mean the comprehensive understanding of left, secular, labor, all kinds of folks coming together and in the short run working to an electoral victory, but in the long run, doing the cultural work needed to actually take out the toxic poison that has just been there in India’s capillary for a very long time.

SV: Thank you so much for joining us today. And, thank you for laying out not just the historical but cultural aspects of Hindutva. As we finish this conversation, I just want to add that the list of Balmurli’s work will be in the links below. From The Polis Project, we urge all of the Indians who are of the eligible age to vote, to go and vote. And I know that a lot of diasporas are now going back to India to vote, so if that’s a possibility, please do. Thank you.

BM- Thank you very much, Suchitra and I do want to say that Hindutva is very much there in the diaspora and maybe we can have another discussion on that.

READING LIST

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.

Related Posts

- Conversations

Billionaires are being produced at the same time that people are actually dying from lack of food – A conversation with Balmurli Natrajan