In “post-conflict” Punjab, state violence has left a maze of collective memories that refuses to die

But India’s meta-archive has no space to preserve the labour of Sikh women who navigated dangerous, masculine spaces from torture centres to the courts for their disappeared loved ones.

Two years ago I traveled about ten villages of Gurdaspur in Punjab for my fieldwork. I also helped in documenting and recording testimonies of families whose near and dear ones were extrajudicially killed or subjected to enforced disappearance by the counterinsurgency grid in the state between 1984 and 1995. These would later be taken up for litigation by the Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project, the group involved in the documentation. It’s been more than two decades since the Indian establishment committed such mass atrocities in Punjab. Even so, there remains a sense of painful yet profound attachment to a collective past, a comradery, and a frail hope for closure. In every village I went, residues of violence were palpable and remained uncomfortably inscribed on bodies and space.

One day, we had to cross the Batala-Amritsar road to reach a family I had promised to visit and record their testimony. I knew that somewhere along that route I would find “Beeco,” the infamous interrogation centre referred to by a number of Sikh families during my documentation. Beeco was a factory for making iron plates and rods before it was taken over and occupied by the police for the purpose of “interrogation” of alleged Sikh militants and their sympathisers. It is now an abandoned piece of land, lined by trucks and construction material. A large square-shaped, rusted metal gate lies gutted in weed, garbage, and soil. It is situated in contiguity to the city, enmeshed with the everydayness of a busy crossroads that is home to shops, banks, eating joints, and general stores. I knew I had to spend long days around the abandoned place, to foreground the centrality of the effects of terror that linger in the memories of hundreds of Sikh men. But, some other day.

A bag on the wall

On our way, my local guide and I were helped by villagers old and young to reach the home of Bibi Rani Kaur. In the countryside, people remembered homes through a history of ruptures and absences. “Do you know the house of the person who was killed by the police,” we would ask. And they gave us directions or accompanied us to lanes, farms, and homes.

Kaur, 80, lost her son Jyot Singh in the early 1990s. Singh was killed in the custody of the Punjab police. However, he remained undocumented and Bibi Kaur had agreed to record her testimony. Most key witnesses in cases of extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances in Punjab are aged parents and relatives. To document state violence is therefore a matter of urgency.

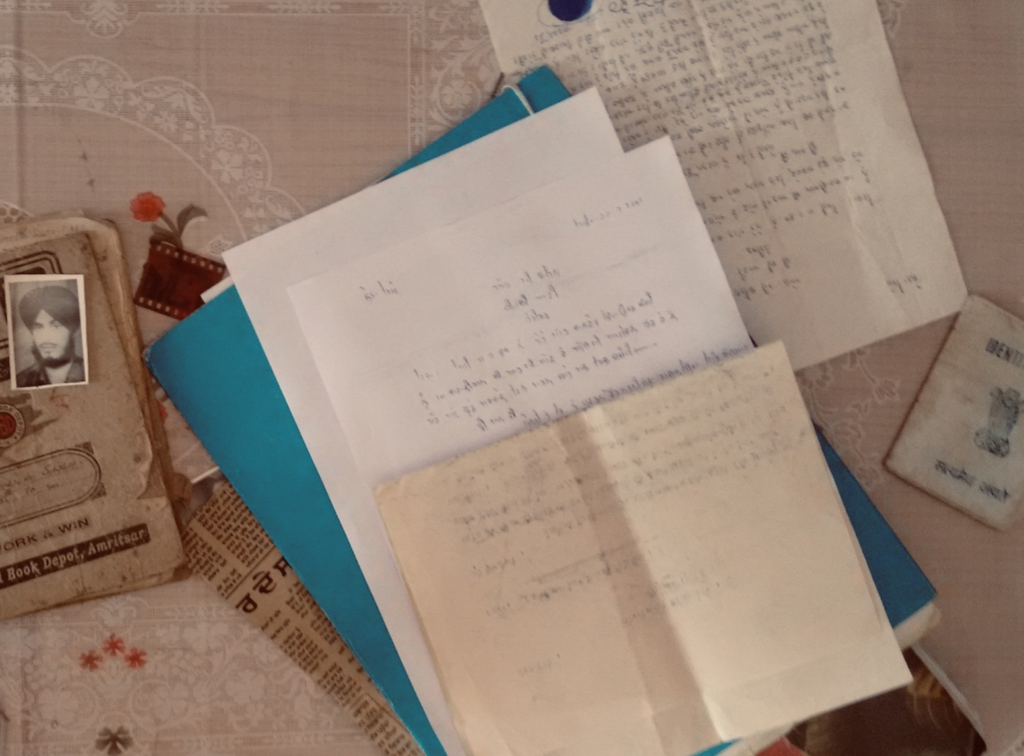

She asked her elder son to hand over a green bag hanging on the wall. Personal memorabilia embodied the materiality of absence in every household which has endured state violence in Punjab. These were kept in a folder or a plastic bag and had documents, photographs, telegrams to authorities, habeas corpus petitions, newspaper clippings, and sometimes police FIRs (first information reports).

The creases of Kaur’s hands foretold the burden of memory of the kaala daur—dark times—as the people of Punjab describe the period. Decades have passed but the documents that she preserved—case files, letter sent by her son from jail, letters written to lawyers—are testament to an erased life.

The letter written by Singh from prison was laminated, its last words preserved with more care. It had reached the family through another villager who had gone to meet a relative in the same prison. Written in Punjabi, it contained spine-chilling details of the torture inflicted by the police on him. Singh writes that he couldn’t stand on his feet and urges his father to arrange for a lawyer so he could be produced in a court. I remembered advocate Brijinder Singh Sodhi’s words during the Independent People’s Tribunal in Amritsar in 2017 detailing how undertrials would be carried by another person in their arms so that they could appear for court hearings. Such was the pervasive use of torture.

Singh goes on to say that it was better to be jailed in a false case—at least that could save his life. The terror of being killed in a fake encounter (extra-judicial killing by the police) loomed throughout his words.

Singh was killed a few days after he wrote this letter.

“Ajmer Singh died waiting for justice,” Kaur said of her husband. Ajmer passed away a few years ago. He ran from pillar to post, writing applications, meeting lawyers and police officers. Once, a police officer from Chandigarh approached the family and offered a job for Singh’s brother on the condition that they stopped all efforts to get a case registered against the police officers. Ajmer categorically refused and told the officer that he wanted justice, not jobs.

“Where do we get justice these days,” she asked me.

I informed her that she was entitled to a compensation of 250,000 Indian rupees, following the orders of the supreme court.

“Gareebi-ameeri kat jaundi hai, bandeya da ki kariye?” One lives through financial ups and downs, what do you do about a person (disappeared), she asked.

In the midst of sorrow, she held my hand as she sat on her bed looking towards the flowing golden fields of wheat. The silence that followed became a discomfort that I felt in my body through my journey after. Will my words ever convey the loss endured by these families? Provisions of law may decide on the quantum of compensation and punishment, but who can know the depths of injury and pain better than Kaur?

A running thread

Documentation was critical to resist erasure and initiate legal proceedings. I am always moved by these motivations which are a running thread that binds families in Punjab. Like what Baldev Singh’s family did that day has stayed with me to this day.

Testimonial account of Baldev’s family reveal that he was killed along with Mukhtar Singh by the Punjab police in a fake encounter in September 1989. Both were subjected to gruesome torture in different police stations but were killed together on the same day near a village that came under the jurisdiction of the Kathunangal Police station.

I listened to Joginder Singh, Baldev’s elder brother, trying my best to ensure his testimony was recorded accurately. He, in turn, made arduous efforts to ascertain the whereabouts of Mukhtar’s surviving family. One phone call led to another for about half an hour until we got in touch with Mukhtar’s son, Arjun Singh. Mukhtar was not listed in the record maintained by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in the Punjab Mass Illegal Cremations case. However, Joginder was certain that both were killed together and their bodies were cremated on the same funeral pyre. This clandestine method of disposing dead bodies was a common practice employed by the counterinsurgency apparatus in Punjab. It enabled concealment and obfuscation of death, both materially and statistically.

Joginder did not carry home the remains of his dead brother. The violations of human dignity persisted beyond deaths. Traditional and religious rituals of last rites made little sense. He also told me that Mukhtar’s father did not convey the news of his killing to Mukhtar’s wife, Baljeet Kaur, who had fallen seriously ill when the police picked him up from his home. The father was worried the news of his death would devastate her.

On the same day we managed to reach Mukhtar’s village. Baljeet sat with us while her daughter gave us a file. “I remember everything. I don’t need these documents to tell you my story,” Baljeet said. She gave us the date of her husband’s abduction, the names of the police officers who picked him up, and said that her mother-in-law (now deceased) went to the police station every day for eleven days with food for Mukhtar. But after that Mukhtar was never seen again. These were the exact details that I read in the photocopies of the petition to the NHRC.

Mukhtar’s whereabouts were thus stated to be unknown after the last day he was seen in police custody. He had “disappeared.” And, therefore, these were the only details his wife repeated a number of times as she played with her new-born grandson.

Mukhtar’s whereabouts remained ambiguous for his wife to this day. Her daughter told me that Baljeet had herself travelled all the way to Delhi to submit the petition to the NHRC. Suddenly, it was my responsibility to share devastating information with the family.

I asked for water.

I knew I had to tell Mukhtar’s children, who were now my age, that he in fact was killed. It had to be conveyed in as many words even when I was aware that the family in the deepest of their heart knew that he wasn’t alive.

I had teared up and as I composed myself, Arjun, Mukhtar’s son, looked at me and nodded a little. He didn’t want me to share details in the presence of his mother. “She is not okay,” he said. Later he told me that his mother’s mental health had deteriorated immensely over time: “She has forgotten her own struggle.”

Persistence of violence

Sikh women have largely been erased from the narrative of conflict in Punjab even though my research tells a different story. It was the women who navigated dangerous, masculine spaces like torture centres, police stations, and courts as theysearched for their loved ones after they were abducted by the police or paramilitary. The nation’s meta-archive of Punjab has no space for this labour to preserve memory.

I tried to make sense of the complex topography of collective memory that my journey unfolded. In ensuring that we reach out to Mukhtar’s family, Baldev’s brother affirmed the bonds of solidarity enmeshed in shared memory of loss and trauma. Mukhtar’s father’s concern for his daughter-in-law is now linked to the care of his grandchildren too. The securing and reproduction of traditional gender roles leads him to elide the knowledge of his son’s killing even from his wife and consequently to the petition submitted to the NHRC. The application refers only to the abduction of Mukhtar.

This meant that Mukhtar’s case was excluded from the list of deemed custody cases, a category devised by the NHRC where the police admitted custody of the victim wrongfully cremated but did not admit liability for the unlawful killing. Arbitrary judicial taxonomies and absence of investigations meant that even though Mukhtar’s family was entitled to a compensation of 500,000 Indian rupees—like that of Baldev since they were killed together—for the NHRC Mukhtar’s body did not even exist.

How could it when it was clandestinely reduced to ashes?