Marked, Detained, Pushed Back: Inside India’s New Deportation Regime

Every June 30, Ruksar Khan and her sisters celebrate their father’s birthday with chocolate cake. This year, the cake remained on one side of a video call in Mumbai. Their father, Dadamiya Khan, marked his 48th birthday 2,000 kilometers away in Bangladesh, the country he had left as a child.

On the call, his three daughters, Ruksar (18), Rehana (16), and Ayesha (8), pleaded with him to come home. “But Papa told us that he would come back only when he was allowed to return. He did not want to risk returning illegally,” said Rehana.

Dadamiya is among nearly 1,900 people pushed across the border into Bangladesh by Indian authorities after being detained in Maharashtra this year. The deportations are part of an intensified nationwide drive that followed both the political upheaval in Bangladesh and the April 22 militant attack on Indian tourists in Jammu and Kashmir.

As ethnic Bengali Muslims and Bengali-speaking migrant workers are rounded up under suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals, families are being torn apart. Media reports have also documented cases of Bengali-speaking Muslim Indians being wrongfully deported. Human rights groups and legal experts say the speed and opaqueness of the exercise, launched a national security response, raise grave concerns about violations of people’s right to due process.

Detention and Separation

Four decades back, Dadamiya’s parents had come to India and left him in the care of an uncle in West Bengal, Ruksar said. The uncle took young Dadamiya to Mumbai, where he grew up and made a living as a driver until he was deported, at age 47.

The police came for Dadamiya Khan on the night of May 15. He had come home late for dinner. He was taken along with his wife Mariyam, who was running a high fever, and his daughters to a police station in Mumbai’s eastern suburbs, according to the family.

The police allowed Mariyam to leave after ascertaining that both her parents were Indian citizens. Ruksar was detained in a counselling room for women on the first floor of the station. Downstairs, Rehana and eight-year-old Ayesha allegedly heard their father’s cries as policemen took turns beating him in the next room.

“They kept saying that we are all Bangladeshis and that we would be sent back,” Ruksar told The Polis Project. Rehana said she saw police personnel examine their school records, photo identification cards, and her father’s salary slips.

When contacted, a senior Mumbai Police official denied that Rehana and Ayesha were detained at the police station or that Dadamiya was assaulted in custody.

Over the next few days, the fate of Dadamiya and his daughters was decided by a quasi-judicial officer designated as the nodal authority by the Mumbai Police to hear deportation cases of Bangladeshi nationals.

On May 17, just two days after their detention, the Foreigners Registration Office in Mumbai issued a restriction order to Dadamiya and Ayesha. The order noted that neither possessed a passport or visa.

Over the next few days, the fate of Dadamiya and his daughters was decided by a quasi-judicial officer designated as the nodal authority by the Mumbai Police to hear deportation cases of Bangladeshi nationals.

The order confined them to the police station till they were to be deported, “as there is all likelihood that you may go untraceable and/or indulge in undesirable activities in India,” it stated. It also noted that Dadamiya was a native of Jessore district in Bangladesh.

On the third night of their detention, Rehana made a pretext to use the phone and called Neela Limaye, who heads a local unit of Jawahar Bal Manch, an affiliate of the Indian National Congress party. The organization educates children aged 7 to 18, and all three girls regularly attend classes there.

Limaye and her colleagues rushed to the police station. “We were shocked to see that the police had illegally detained minor girls,” she said. She filed a complaint at the Maharashtra Child Welfare Committee. Following an urgent hearing, the committee ordered the police to release Rehana and Ayesha, Limaye said.

Limaye also found a lawyer, Prabha Sontakke, who specializes in familial disputes. “During the hearing, Ayesha kept clinging to me, asking when she would be able to go home,” Sontakke said.

Another lawyer, Raj Dani, then moved a habeas corpus petition before the Bombay High Court to free Ruksar from unlawful detention. The police had still not filed a first information report against Ruksar and Dadamiya to formally charge them with committing a crime, Dani informed.

On June 3, the court ordered the police to release Ruksar immediately. By then, Ruksar had been detained at the police station for over a fortnight.

Without Limaye’s intervention, Ruksar said, she and her sisters would surely have been sent to Bangladesh. The lawyers said they also attempted to prove that Dadamiya was an Indian citizen by producing a photocopy of one page of his passport. But it was too late.

On May 31, he was put on a train bound for West Bengal at Mumbai’s Lokmanya Tilak Terminus along with several dozen other deportees. Before departing, Mariyam had packed her husband a bag filled with clothes, food, and medicines. She would next hear from him only after he was on the other side.

Dadamiya told his family that after arriving in West Bengal, police personnel who had accompanied the deportees from Mumbai handed them over to the BSF, who then drove the group to a camp on the international border.

“Papa said that once night fell, the group was marched into a forest. The BSF men threatened to shoot anyone who turned back,” Ruksar narrated.

The BSF, Ruksar alleged, forced the deportees to swim across a river in darkness. “Papa’s bag, which also had his phone and sim card, got washed away. But he survived because he knew how to swim. Many others did not.”

Once in Bangladesh, Dadamiya searched for his parents’ house and reached there after a half-day’s walk. He has remained there since.

A New Deportation Regime

Following the attack in Pahalgam in April, the home ministry issued a new standard operating procedure on May 2. In a distinct move, it waived the requirement for police departments to communicate with the government of Bangladesh before deporting its nationals.

Instead, the police now simply hand over a person they suspect is an undocumented Bangladeshi national to the Border Security Force (BSF), which secures India’s border with Bangladesh, or to the Assam Rifles, which patrols the Myanmar border. The BSF has allegedly forced deportees to walk into Bangladesh in an exercise termed “pushbacks”.

Under the new SOP, police no longer need to file FIRs. Instead, a quasi-judicial nodal authority determines nationality and issues deportation orders. In “emergency situations,” the BSF or Assam Rifles can directly deport individuals from holding centres.

This intensified deportation regime also follows the introduction of a new immigration legislation. Tabling the Immigration and Foreigners Bill, 2025, in March, Home Minister Amit Shah had framed undocumented migration as a national security threat, declaring in Parliament that India was not a “dharamshala (guest house) where anyone can come and stay for any purpose”. The bill was passed, and the law was enacted in April. Under this, the Union government has directed every state and Union Territory to set up holding centres or detention camps to restrict the movement of illegal foreigners till they are deported.

The Procedure of ‘Pushback’

The new SOP was put in place soon after protests in Bangladesh forced then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to flee and seek asylum in India, according to a senior police official in Maharashtra.

“Relations between the two countries have soured since the regime change. Since then, central government agencies have repeatedly apprehended Bangladeshi nationals staying in India without valid documents, saying they could pose a security threat,” the official told The Polis Project.

A near-fatal attack on Bollywood actor Saif Ali Khan also set off a fresh round of surveillance and detention of Bangladeshi nationals in Mumbai and its neighbouring cities, said another senior police official. The alleged attacker was Shariful Islam Shehzad, a 30-year-old Bangladeshi and restaurant employee who had illegally entered India.

Under the new SOP, the police are no longer required to file FIRs against foreigners suspected of staying illegally. An arrest means that a suspected undocumented foreigner is protected from deportation unless convicted or if they enter a guilty plea during the trial.

The new procedure that deputes a quai-judicial authority to hear deportation cases replaces a criminal trial.

The fate of the apprehended individual is usually decided over three to four sessions spread out over several days. The nodal authority weighs the evidence submitted by the police and, if satisfied, issues a deportation order. The police official added that individuals detained on suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals are produced before the nodal authority and given a chance to defend themselves, with the choice of being represented by a lawyer.

As in a trial, the official added, the detainee’s Bangladeshi nationality has to be proved beyond doubt. “The only way to do that is to obtain identity documents issued by the government of Bangladesh. Simply admitting to being a Bangladeshi national or calling phone numbers in Bangladesh is not enough,” said the official.

For suspected Bangladeshi nationals who claim Indian citizenship, the SOP directs states to verify their residential addresses from states where they claim domicile, within 30 days. Till then, the suspects are to be held in detention centres. The Maharashtra government last year approved the establishment of two detention centres with a capacity for 293 detainees. If no report is received from those states after 30 days, the detaining states are directed to deport the suspects.

In the case of people like Dadamiya Khan, the SOP directs the police to deport suspects once they are determined to be Bangladeshi nationals after capturing their photos and fingerprints.

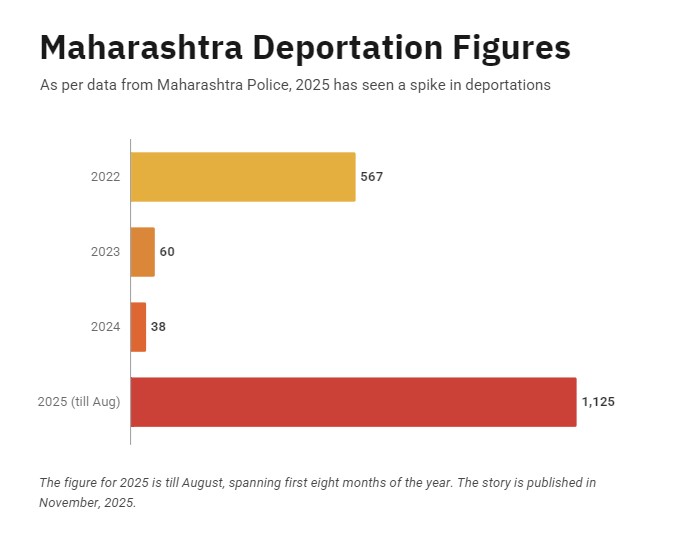

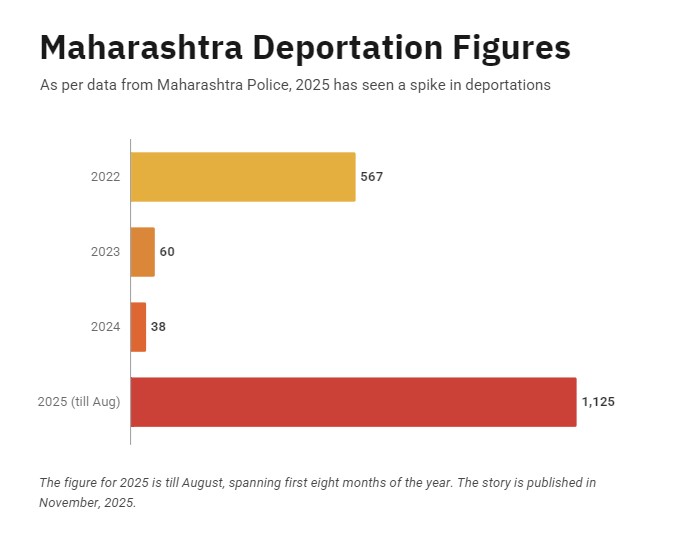

Maharashtra has recorded a sharp spike in deportations in 2025. According to data available with the Maharashtra Police, 567 individuals were deported in 2022, followed by another 60 in 2023. In 2024, the deportations dipped to 38. As of August 2025, the police had deported 1,125 individuals. The current year began slowly – 42 individuals were deported in the first five months. After the new SOP was issued, 544 individuals were deported in June, 328 in July, and 201 in August.

The Mumbai Police, which maintains its own records, also reported a sharp increase in deportations: from 65 in 2023, to 156 in 2024, and rising sixfold to 1001 as of November 17, 2025.

Two senior police officials in Mumbai and the neighboring city of Thane said on the condition of anonymity that the new SOP has made the deportation process “easy and effective.”

“Earlier, we deported illegal Bangladeshi nationals only at the end of a trial. Now, we do not file FIRs. We check a person’s documents, establish their nationality, issue a deportation order, book seats on a flight or train and hand the deportee over to the BSF,” one official said.

The second official said that flight services for deportees have relieved the police of having to send an escort party. “Earlier, if we sent 50 deportees to the border by train, we would have to send an escort party of 20-30 police personnel along with them.” Further, the SOP says the union government will reimburse the states for costs incurred in transporting deportees to the border.

There is a glaring contradiction between SOP directions and practice on the ground with regard to the First Information Report (FIR), and the arrests it enables. Despite the SOP waiving away the requirement of FIRs, arrests of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in Maharashtra continue to rise, from 198 in 2023 to 490 as of August, 2025. The Mumbai Police registered 401 offences between January 1 and November 17, 2025. An analysis of police records of Mumbai and its neighbouring towns shows that between May and August 1, the police had filed 102 FIRs against Bangladeshi immigrants, accusing them of illegally staying in Mumbai.

The FIRs reveal how the police verify the nationality of a suspected Bangladeshi national: cops scan their phones for audio and video calls made to Bangladesh and by order relatives of the detainees to send their national identity cards. Nearly all the FIRs are identical in alleging that the accused persons crossed illegally into India due to the lack of economic opportunities in Bangladesh.

Another common feature of these FIRs is the use of IMO, an application used to send messages and make video and audio calls in areas with weak mobile signal strength. The use of IMO, along with a dozen other apps, was prohibited in 2023 after the Indian government claimed these were being used by terror groups active in Jammu and Kashmir.

A third police official, who asked to remain anonymous, explained that FIRs were being registered in cases where the police were confident that the suspect was staying illegally in India. “In some cases, there are also other offences involved, like human trafficking or obtaining national identification documents through fraudulent means. In cases where we are sure that the evidence will hold up during trial, we are registering FIRs,” the official said.

On this, Darshana Mitra, assistant professor of law at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru, said that when an FIR is filed, it can be contested. “An FIR is only registered if you are definitely a foreigner and there is some material (evidence) against you,” she said.

Concerns Over Due Process and Human Rights

In the same month the SOP was issued, reports emerged about the Union Home Ministry directing all states and union territories to constitute district-level Special Task Forces to identify and deport suspected illegal Bangladeshi and Rohingya migrants within 30 days. Framed as a security response, the directive effectively gives state governments a free hand to carry out expansive surveillance, detention, and expulsion exercises in coordination with central agencies.

The order mandates the collection of detailed personal data, physical verification, confinement in holding centres, and the recording of biometric information on the Foreigners’ Identification Portal, and requires Indian citizenship claims to be resolved within a month. By compressing timelines and devolving sweeping discretionary powers to states, the policy could deepen precarity for migrant and minority communities while eroding procedural safeguards under the guise of national security.

Mitra said that India’s ongoing deportation of alleged Bangladeshi nationals bypasses nationality verification processes. Ordinarily, a deportation request would go from the Union Home Ministry to the Ministry of External Affairs to the Bangladesh government.

“If Bangladesh confirms that the person is its national, it will issue a travel permit if the national does not have a passport,” she said.

Mitra, who has challenging deportations in courts in Delhi, is finding it hard to understand what the process is now. Only courts can determine foreign citizenship, or the Foreigners Tribunal in the case of Assam, or it can be ascertained by an individual’s own admission, she said. “The May 2 SOP makes things unclear,” she added.

Since the Pahalgam attack, Mitra has observed an “executive pressure to remove” illegal Bangladeshi immigrants and “to strike fear within the community.” “This is more of a Pahalgam reaction. We respond to a terror attack through immigration control even though there is no correlation between the two,” the law professor said.

US-based watchdog group Human Rights Watch, which conducted its own investigation into the deportations in June, called on the Indian government to “stop unlawfully deporting people without due process.”

The report quoted Elaine Pearson, the organization’s Asia director, as saying, “India’s ruling BJP is fueling discrimination by arbitrarily expelling Bengali Muslims from the country, including Indian citizens. The authorities’ claims that they are managing irregular immigration are unconvincing given their disregard for due process rights, domestic guarantees, and international human rights standards.”

Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), a Mumbai-based civil society organisation, found that the detentions and deportations were launched in a “co-ordinated manner” following the Pahalgam terror attack and the military engagement between India and Pakistan. This exercise “squarely plays into public sentiment that remains silent or ‘allows’ such unlawful actions,” it said.

CJP has been documenting and challenging deportations in BJP-ruled Assam, a state where the chief minister, Himanta Biswa Sarma, posts on his X account pictures of individuals pushed back into Bangladesh. CJP has accused Sarma’s government of committing a “stealth administrative purge targeting a vulnerable minority community”.

In May, CJP had submitted a memorandum containing evidence that the Assam police had conducted night raids and detained at least 300 people, most of them Bengali-speaking Muslims. Of those detained between May 23 and 31, as many as 145 people were feared to have been “disappeared under highly suspicious and unlawful circumstances.” The individuals had been picked up from their homes without being served warrants or an explanation. The reasons for their detention were not explained to their families, as required by law, the memorandum said.

“No legal counsel was allowed. Families were left in the dark about their whereabouts or safety,” the memorandum stated.

Writing on October 2, after his government pushed back 22 people, Sarma said, “illegal infiltrators” were “modern-day evils”. Alongside, he shared a photo showing a group of children, men, and women, some holding toddlers, standing in the dark; their faces were blurred.

Assam occupies a distinctive position within India’s new deportation regime because the state has a long history of political mobilisation over alleged “Bangladeshi” migration as a threat to land, language, and political power. This legacy was institutionalized through the National Register of Citizens and Foreigners’ Tribunals, making Assam the only state where citizenship determination functioned outside regular criminal courts. While the new SOP marks a procedural break for other states, Assam reflects a continuity when it comes to executive discretion rooted in long-standing suspicion of Bengali Muslims.

In a later report, the CJP said that detentions and deportations in BJP-ruled states had taken place with “no public disclosures on procedures and documents to legally and constitutionally justify the process.”

Soon after the SOP announcement, Samirul Islam, a member of the Upper House of the Parliament from the opposition party Trinamool Congress, wrote a letter to the home minister. He asked for “thorough verification procedures before initiating any action against individuals claiming origin from West Bengal” and to “enforce mandatory coordination with the West Bengal government in cases where any Bengali-speaking person is found to be in distress.”

Politics, Policy, and Bengali Migrant Workers

The deportation exercise has disproportionately affected Bengali-speaking migrant workers from West Bengal, which shares borders with Bangladesh. Samirul Islam, who hails from West Bengal, had noted in his letter an escalation in “targeted hostility” against Bengali-speaking migrant workers. “Alarmingly, a majority of these incidents have been reported from BJP-governed states, including Odisha, Maharashtra, and Gujarat,” he had said.

Islam, the Chairman of the West Bengal Migrant Workers’ Welfare Board, estimates that 22 lakh people from his state currently work in various formal and informal sectors across India. He said that even before the Pahalgam attack, he had received complaints of Bengali migrant workers being harassed by locals in other states and detained by police, but not of deportations.

“Since the Pahalgam attack, the police in BJP-ruled states have been breaking shop signboards written in Bengali. They are accusing Bengali citizens of being Bangladeshi nationals. Our own people are being beaten up and sent to Bangladesh. This did not happen before April,” he said.

Gujarat was the “first off the blocks”, accounting for almost half of more than 2,000 individuals deported to Bangladesh in the first three weeks after the outbreak of the military conflict between India and Pakistan on May 7.

In the same week as the Pahalgam attack, police in Ahmedabad and Surat, cities in Gujarat, detained more than 1,000 people, including children, suspected of being illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The detentions were followed by the state bringing in bulldozers to demolish nearly 10,000 homes built around Chandola, an encroached lake in Ahmedabad. An Economic Times report in May said that of the 250 illegal Bangladeshi nationals detained in the city then, 207 were from Chandola.

Delhi also saw similar crackdowns. In the first half of 2025, the Delhi police detained and deported 770 people accused of being Bangladeshi nationals. Of these, more than 500 people were deported just a month after the Pahalgam attack.

A few of these were wrongful deportations. The Delhi police detained six members of two families in its search for illegal Bangladeshis. In June, the BSF pushed these two families hailing from West Bengal’s Birbhum across the border into Bangladesh. The group comprised Sunali Khatun, who was eight months pregnant at the time, her husband Danish, and their eight-year-old son; Sweety Bibi and her two young sons.

Islam helped the parents of Sunali and Sweety to approach the Calcutta High Court, which ordered the Indian government in September to bring the group back. Then a court in Bangladesh, where the group was charged with straying into the country, recognized them as Indian citizens and directed the Indian High Commission in Dhaka to repatriate them to India.

Mehbub Sheikh, a 36-year-old Bengali migrant worker living in Thane near Mumbai, was deported to Bangladesh despite his family submitting documents establishing his Indian citizenship. He was among five men who, like Dadamiya, were pushed across the border at night by the BSF. Sheikh’s brother Mujibur told The Indian Express that police moved him to a BSF camp in West Bengal a day after the family sent his voter ID, Aadhaar, and ration card, but officials dismissed these, citing the absence of a birth certificate.

Sheikh was eventually brought back after his family approached Islam, who intervened with the central government and the BSF, leading to coordination with Bangladeshi authorities for his return.

Since then, the BJP in Maharashtra has intensified allegations that Bangladeshi nationals have illegally obtained birth certificates. Kirit Somaiya, a former MP from Mumbai’s eastern suburbs, sought data on birth certificate approvals in 2024 under the Right to Information act. He argued that Aadhaar cards tied to “fraudulently acquired” certificates should be cancelled. On October 13, he led a protest over an alleged “Bangladeshi birth certificate scam” near the police station where Dadamiya’s family was detained and called for a “combing operation” in Mumbai’s eastern suburbs.

Similar claims had surfaced during Delhi’s state election campaign earlier this year. BJP leaders had accused the then-ruling Aam Aadmi Party of facilitating Aadhaar cards for Bangladeshi immigrants and manipulating the city’s demography. Eventually, the BJP returned to power in Delhi after 25 years.

However, this pitch was cited as one of the reasons it failed to wrest control of Jharkhand state in last year’s elections. The election campaign for the eastern Indian state also featured claims from senior BJP leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who made “illegal Bangladeshi immigration and infiltration” a major poll plank.

In campaign rallies, the chief ministers of Assam and Uttar Pradesh states, and Modi, all had accused the ruling Jharkhand Mukti Morcha party of “patronising infiltrators”. “If this continues, the tribal population in Jharkhand will shrink. This is a threat to tribal society and the country,” Modi had claimed. The Polis Project investigated and debunked these claims.

How a Broken Family Struggles to Survive

Since Dadamiya’s deportation, his wife Mariyam has taken on a second job sorting nuts for packaging at a small facility near her home, in addition to laboring as a domestic worker.

Even so, the family’s finances are precarious. They have to pay back a loan given by Dadamiya’s employer to admit Rehana to her preferred college to pursue higher studies. Hence, Mariyam can no longer afford to send Ayesha to after-school coaching classes.

Rehana has taken to pleading with people whom Dadamiya had lent money, like friends and neighbours, to pay them back. The family does not have the finances to challenge Dadamiya’s deportation legally.

“They had taken a loan of Rs. 45,000, of which Rs. 25,000 is still to be repaid. Until they do that, they cannot afford to go to court for Dadamiya,” said Limaye, who helped arrange for the loan.

Dadamiya’s daughters speak to him every day. Speaking about his condition, Ruksar said, “Papa is unable to find work there. No one will hire him there because he has no documents to show that he is Bangladeshi. He got work one day at a farm. At the end of the day, he was paid 200 taka.”

The girls have now applied for age, domicile, and nationality certificates from their local municipal corporation. They are eligible since Mariyam’s Indian citizenship is not in doubt. Mariyam had submitted her Aadhaar and PAN cards, as well as records of the land owned by her family in their native village, to the police. The land records, said a police official privy to the case, showed that Mariyam’s family had been living in India for several generations.

Dadamiya, however, had attempted to get a certificate for himself late last year when the police were rounding up other Bangladeshi nationals around him.

“Father thought that once he got the certificate he would be safe from deportation. But the lawyer he had approached said his birth certificate was not genuine so he gave up trying to get the document,” Rehana said.

Ruksar is hopeful the nationality certificates will enable her to see her father again. Until then, he is only a face on the screen.

Every June 30, Ruksar Khan and her sisters celebrate their father’s birthday with chocolate cake. This year, the cake remained on one side of a video call in Mumbai. Their father, Dadamiya Khan, marked his 48th birthday 2,000 kilometers away in Bangladesh, the country he had left as a child.

On the call, his three daughters, Ruksar (18), Rehana (16), and Ayesha (8), pleaded with him to come home. “But Papa told us that he would come back only when he was allowed to return. He did not want to risk returning illegally,” said Rehana.

Dadamiya is among nearly 1,900 people pushed across the border into Bangladesh by Indian authorities after being detained in Maharashtra this year. The deportations are part of an intensified nationwide drive that followed both the political upheaval in Bangladesh and the April 22 militant attack on Indian tourists in Jammu and Kashmir.

As ethnic Bengali Muslims and Bengali-speaking migrant workers are rounded up under suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals, families are being torn apart. Media reports have also documented cases of Bengali-speaking Muslim Indians being wrongfully deported. Human rights groups and legal experts say the speed and opaqueness of the exercise, launched a national security response, raise grave concerns about violations of people’s right to due process.

Detention and Separation

Four decades back, Dadamiya’s parents had come to India and left him in the care of an uncle in West Bengal, Ruksar said. The uncle took young Dadamiya to Mumbai, where he grew up and made a living as a driver until he was deported, at age 47.

The police came for Dadamiya Khan on the night of May 15. He had come home late for dinner. He was taken along with his wife Mariyam, who was running a high fever, and his daughters to a police station in Mumbai’s eastern suburbs, according to the family.

The police allowed Mariyam to leave after ascertaining that both her parents were Indian citizens. Ruksar was detained in a counselling room for women on the first floor of the station. Downstairs, Rehana and eight-year-old Ayesha allegedly heard their father’s cries as policemen took turns beating him in the next room.

“They kept saying that we are all Bangladeshis and that we would be sent back,” Ruksar told The Polis Project. Rehana said she saw police personnel examine their school records, photo identification cards, and her father’s salary slips.

When contacted, a senior Mumbai Police official denied that Rehana and Ayesha were detained at the police station or that Dadamiya was assaulted in custody.

Over the next few days, the fate of Dadamiya and his daughters was decided by a quasi-judicial officer designated as the nodal authority by the Mumbai Police to hear deportation cases of Bangladeshi nationals.

On May 17, just two days after their detention, the Foreigners Registration Office in Mumbai issued a restriction order to Dadamiya and Ayesha. The order noted that neither possessed a passport or visa.

Over the next few days, the fate of Dadamiya and his daughters was decided by a quasi-judicial officer designated as the nodal authority by the Mumbai Police to hear deportation cases of Bangladeshi nationals.

The order confined them to the police station till they were to be deported, “as there is all likelihood that you may go untraceable and/or indulge in undesirable activities in India,” it stated. It also noted that Dadamiya was a native of Jessore district in Bangladesh.

On the third night of their detention, Rehana made a pretext to use the phone and called Neela Limaye, who heads a local unit of Jawahar Bal Manch, an affiliate of the Indian National Congress party. The organization educates children aged 7 to 18, and all three girls regularly attend classes there.

Limaye and her colleagues rushed to the police station. “We were shocked to see that the police had illegally detained minor girls,” she said. She filed a complaint at the Maharashtra Child Welfare Committee. Following an urgent hearing, the committee ordered the police to release Rehana and Ayesha, Limaye said.

Limaye also found a lawyer, Prabha Sontakke, who specializes in familial disputes. “During the hearing, Ayesha kept clinging to me, asking when she would be able to go home,” Sontakke said.

Another lawyer, Raj Dani, then moved a habeas corpus petition before the Bombay High Court to free Ruksar from unlawful detention. The police had still not filed a first information report against Ruksar and Dadamiya to formally charge them with committing a crime, Dani informed.

On June 3, the court ordered the police to release Ruksar immediately. By then, Ruksar had been detained at the police station for over a fortnight.

Without Limaye’s intervention, Ruksar said, she and her sisters would surely have been sent to Bangladesh. The lawyers said they also attempted to prove that Dadamiya was an Indian citizen by producing a photocopy of one page of his passport. But it was too late.

On May 31, he was put on a train bound for West Bengal at Mumbai’s Lokmanya Tilak Terminus along with several dozen other deportees. Before departing, Mariyam had packed her husband a bag filled with clothes, food, and medicines. She would next hear from him only after he was on the other side.

Dadamiya told his family that after arriving in West Bengal, police personnel who had accompanied the deportees from Mumbai handed them over to the BSF, who then drove the group to a camp on the international border.

“Papa said that once night fell, the group was marched into a forest. The BSF men threatened to shoot anyone who turned back,” Ruksar narrated.

The BSF, Ruksar alleged, forced the deportees to swim across a river in darkness. “Papa’s bag, which also had his phone and sim card, got washed away. But he survived because he knew how to swim. Many others did not.”

Once in Bangladesh, Dadamiya searched for his parents’ house and reached there after a half-day’s walk. He has remained there since.

A New Deportation Regime

Following the attack in Pahalgam in April, the home ministry issued a new standard operating procedure on May 2. In a distinct move, it waived the requirement for police departments to communicate with the government of Bangladesh before deporting its nationals.

Instead, the police now simply hand over a person they suspect is an undocumented Bangladeshi national to the Border Security Force (BSF), which secures India’s border with Bangladesh, or to the Assam Rifles, which patrols the Myanmar border. The BSF has allegedly forced deportees to walk into Bangladesh in an exercise termed “pushbacks”.

Under the new SOP, police no longer need to file FIRs. Instead, a quasi-judicial nodal authority determines nationality and issues deportation orders. In “emergency situations,” the BSF or Assam Rifles can directly deport individuals from holding centres.

This intensified deportation regime also follows the introduction of a new immigration legislation. Tabling the Immigration and Foreigners Bill, 2025, in March, Home Minister Amit Shah had framed undocumented migration as a national security threat, declaring in Parliament that India was not a “dharamshala (guest house) where anyone can come and stay for any purpose”. The bill was passed, and the law was enacted in April. Under this, the Union government has directed every state and Union Territory to set up holding centres or detention camps to restrict the movement of illegal foreigners till they are deported.

The Procedure of ‘Pushback’

The new SOP was put in place soon after protests in Bangladesh forced then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to flee and seek asylum in India, according to a senior police official in Maharashtra.

“Relations between the two countries have soured since the regime change. Since then, central government agencies have repeatedly apprehended Bangladeshi nationals staying in India without valid documents, saying they could pose a security threat,” the official told The Polis Project.

A near-fatal attack on Bollywood actor Saif Ali Khan also set off a fresh round of surveillance and detention of Bangladeshi nationals in Mumbai and its neighbouring cities, said another senior police official. The alleged attacker was Shariful Islam Shehzad, a 30-year-old Bangladeshi and restaurant employee who had illegally entered India.

Under the new SOP, the police are no longer required to file FIRs against foreigners suspected of staying illegally. An arrest means that a suspected undocumented foreigner is protected from deportation unless convicted or if they enter a guilty plea during the trial.

The new procedure that deputes a quai-judicial authority to hear deportation cases replaces a criminal trial.

The fate of the apprehended individual is usually decided over three to four sessions spread out over several days. The nodal authority weighs the evidence submitted by the police and, if satisfied, issues a deportation order. The police official added that individuals detained on suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals are produced before the nodal authority and given a chance to defend themselves, with the choice of being represented by a lawyer.

As in a trial, the official added, the detainee’s Bangladeshi nationality has to be proved beyond doubt. “The only way to do that is to obtain identity documents issued by the government of Bangladesh. Simply admitting to being a Bangladeshi national or calling phone numbers in Bangladesh is not enough,” said the official.

For suspected Bangladeshi nationals who claim Indian citizenship, the SOP directs states to verify their residential addresses from states where they claim domicile, within 30 days. Till then, the suspects are to be held in detention centres. The Maharashtra government last year approved the establishment of two detention centres with a capacity for 293 detainees. If no report is received from those states after 30 days, the detaining states are directed to deport the suspects.

In the case of people like Dadamiya Khan, the SOP directs the police to deport suspects once they are determined to be Bangladeshi nationals after capturing their photos and fingerprints.

Maharashtra has recorded a sharp spike in deportations in 2025. According to data available with the Maharashtra Police, 567 individuals were deported in 2022, followed by another 60 in 2023. In 2024, the deportations dipped to 38. As of August 2025, the police had deported 1,125 individuals. The current year began slowly – 42 individuals were deported in the first five months. After the new SOP was issued, 544 individuals were deported in June, 328 in July, and 201 in August.

The Mumbai Police, which maintains its own records, also reported a sharp increase in deportations: from 65 in 2023, to 156 in 2024, and rising sixfold to 1001 as of November 17, 2025.

Two senior police officials in Mumbai and the neighboring city of Thane said on the condition of anonymity that the new SOP has made the deportation process “easy and effective.”

“Earlier, we deported illegal Bangladeshi nationals only at the end of a trial. Now, we do not file FIRs. We check a person’s documents, establish their nationality, issue a deportation order, book seats on a flight or train and hand the deportee over to the BSF,” one official said.

The second official said that flight services for deportees have relieved the police of having to send an escort party. “Earlier, if we sent 50 deportees to the border by train, we would have to send an escort party of 20-30 police personnel along with them.” Further, the SOP says the union government will reimburse the states for costs incurred in transporting deportees to the border.

There is a glaring contradiction between SOP directions and practice on the ground with regard to the First Information Report (FIR), and the arrests it enables. Despite the SOP waiving away the requirement of FIRs, arrests of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in Maharashtra continue to rise, from 198 in 2023 to 490 as of August, 2025. The Mumbai Police registered 401 offences between January 1 and November 17, 2025. An analysis of police records of Mumbai and its neighbouring towns shows that between May and August 1, the police had filed 102 FIRs against Bangladeshi immigrants, accusing them of illegally staying in Mumbai.

The FIRs reveal how the police verify the nationality of a suspected Bangladeshi national: cops scan their phones for audio and video calls made to Bangladesh and by order relatives of the detainees to send their national identity cards. Nearly all the FIRs are identical in alleging that the accused persons crossed illegally into India due to the lack of economic opportunities in Bangladesh.

Another common feature of these FIRs is the use of IMO, an application used to send messages and make video and audio calls in areas with weak mobile signal strength. The use of IMO, along with a dozen other apps, was prohibited in 2023 after the Indian government claimed these were being used by terror groups active in Jammu and Kashmir.

A third police official, who asked to remain anonymous, explained that FIRs were being registered in cases where the police were confident that the suspect was staying illegally in India. “In some cases, there are also other offences involved, like human trafficking or obtaining national identification documents through fraudulent means. In cases where we are sure that the evidence will hold up during trial, we are registering FIRs,” the official said.

On this, Darshana Mitra, assistant professor of law at the National Law School of India University, Bengaluru, said that when an FIR is filed, it can be contested. “An FIR is only registered if you are definitely a foreigner and there is some material (evidence) against you,” she said.

Concerns Over Due Process and Human Rights

In the same month the SOP was issued, reports emerged about the Union Home Ministry directing all states and union territories to constitute district-level Special Task Forces to identify and deport suspected illegal Bangladeshi and Rohingya migrants within 30 days. Framed as a security response, the directive effectively gives state governments a free hand to carry out expansive surveillance, detention, and expulsion exercises in coordination with central agencies.

The order mandates the collection of detailed personal data, physical verification, confinement in holding centres, and the recording of biometric information on the Foreigners’ Identification Portal, and requires Indian citizenship claims to be resolved within a month. By compressing timelines and devolving sweeping discretionary powers to states, the policy could deepen precarity for migrant and minority communities while eroding procedural safeguards under the guise of national security.

Mitra said that India’s ongoing deportation of alleged Bangladeshi nationals bypasses nationality verification processes. Ordinarily, a deportation request would go from the Union Home Ministry to the Ministry of External Affairs to the Bangladesh government.

“If Bangladesh confirms that the person is its national, it will issue a travel permit if the national does not have a passport,” she said.

Mitra, who has challenging deportations in courts in Delhi, is finding it hard to understand what the process is now. Only courts can determine foreign citizenship, or the Foreigners Tribunal in the case of Assam, or it can be ascertained by an individual’s own admission, she said. “The May 2 SOP makes things unclear,” she added.

Since the Pahalgam attack, Mitra has observed an “executive pressure to remove” illegal Bangladeshi immigrants and “to strike fear within the community.” “This is more of a Pahalgam reaction. We respond to a terror attack through immigration control even though there is no correlation between the two,” the law professor said.

US-based watchdog group Human Rights Watch, which conducted its own investigation into the deportations in June, called on the Indian government to “stop unlawfully deporting people without due process.”

The report quoted Elaine Pearson, the organization’s Asia director, as saying, “India’s ruling BJP is fueling discrimination by arbitrarily expelling Bengali Muslims from the country, including Indian citizens. The authorities’ claims that they are managing irregular immigration are unconvincing given their disregard for due process rights, domestic guarantees, and international human rights standards.”

Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), a Mumbai-based civil society organisation, found that the detentions and deportations were launched in a “co-ordinated manner” following the Pahalgam terror attack and the military engagement between India and Pakistan. This exercise “squarely plays into public sentiment that remains silent or ‘allows’ such unlawful actions,” it said.

CJP has been documenting and challenging deportations in BJP-ruled Assam, a state where the chief minister, Himanta Biswa Sarma, posts on his X account pictures of individuals pushed back into Bangladesh. CJP has accused Sarma’s government of committing a “stealth administrative purge targeting a vulnerable minority community”.

In May, CJP had submitted a memorandum containing evidence that the Assam police had conducted night raids and detained at least 300 people, most of them Bengali-speaking Muslims. Of those detained between May 23 and 31, as many as 145 people were feared to have been “disappeared under highly suspicious and unlawful circumstances.” The individuals had been picked up from their homes without being served warrants or an explanation. The reasons for their detention were not explained to their families, as required by law, the memorandum said.

“No legal counsel was allowed. Families were left in the dark about their whereabouts or safety,” the memorandum stated.

Writing on October 2, after his government pushed back 22 people, Sarma said, “illegal infiltrators” were “modern-day evils”. Alongside, he shared a photo showing a group of children, men, and women, some holding toddlers, standing in the dark; their faces were blurred.

Assam occupies a distinctive position within India’s new deportation regime because the state has a long history of political mobilisation over alleged “Bangladeshi” migration as a threat to land, language, and political power. This legacy was institutionalized through the National Register of Citizens and Foreigners’ Tribunals, making Assam the only state where citizenship determination functioned outside regular criminal courts. While the new SOP marks a procedural break for other states, Assam reflects a continuity when it comes to executive discretion rooted in long-standing suspicion of Bengali Muslims.

In a later report, the CJP said that detentions and deportations in BJP-ruled states had taken place with “no public disclosures on procedures and documents to legally and constitutionally justify the process.”

Soon after the SOP announcement, Samirul Islam, a member of the Upper House of the Parliament from the opposition party Trinamool Congress, wrote a letter to the home minister. He asked for “thorough verification procedures before initiating any action against individuals claiming origin from West Bengal” and to “enforce mandatory coordination with the West Bengal government in cases where any Bengali-speaking person is found to be in distress.”

Politics, Policy, and Bengali Migrant Workers

The deportation exercise has disproportionately affected Bengali-speaking migrant workers from West Bengal, which shares borders with Bangladesh. Samirul Islam, who hails from West Bengal, had noted in his letter an escalation in “targeted hostility” against Bengali-speaking migrant workers. “Alarmingly, a majority of these incidents have been reported from BJP-governed states, including Odisha, Maharashtra, and Gujarat,” he had said.

Islam, the Chairman of the West Bengal Migrant Workers’ Welfare Board, estimates that 22 lakh people from his state currently work in various formal and informal sectors across India. He said that even before the Pahalgam attack, he had received complaints of Bengali migrant workers being harassed by locals in other states and detained by police, but not of deportations.

“Since the Pahalgam attack, the police in BJP-ruled states have been breaking shop signboards written in Bengali. They are accusing Bengali citizens of being Bangladeshi nationals. Our own people are being beaten up and sent to Bangladesh. This did not happen before April,” he said.

Gujarat was the “first off the blocks”, accounting for almost half of more than 2,000 individuals deported to Bangladesh in the first three weeks after the outbreak of the military conflict between India and Pakistan on May 7.

In the same week as the Pahalgam attack, police in Ahmedabad and Surat, cities in Gujarat, detained more than 1,000 people, including children, suspected of being illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The detentions were followed by the state bringing in bulldozers to demolish nearly 10,000 homes built around Chandola, an encroached lake in Ahmedabad. An Economic Times report in May said that of the 250 illegal Bangladeshi nationals detained in the city then, 207 were from Chandola.

Delhi also saw similar crackdowns. In the first half of 2025, the Delhi police detained and deported 770 people accused of being Bangladeshi nationals. Of these, more than 500 people were deported just a month after the Pahalgam attack.

A few of these were wrongful deportations. The Delhi police detained six members of two families in its search for illegal Bangladeshis. In June, the BSF pushed these two families hailing from West Bengal’s Birbhum across the border into Bangladesh. The group comprised Sunali Khatun, who was eight months pregnant at the time, her husband Danish, and their eight-year-old son; Sweety Bibi and her two young sons.

Islam helped the parents of Sunali and Sweety to approach the Calcutta High Court, which ordered the Indian government in September to bring the group back. Then a court in Bangladesh, where the group was charged with straying into the country, recognized them as Indian citizens and directed the Indian High Commission in Dhaka to repatriate them to India.

Mehbub Sheikh, a 36-year-old Bengali migrant worker living in Thane near Mumbai, was deported to Bangladesh despite his family submitting documents establishing his Indian citizenship. He was among five men who, like Dadamiya, were pushed across the border at night by the BSF. Sheikh’s brother Mujibur told The Indian Express that police moved him to a BSF camp in West Bengal a day after the family sent his voter ID, Aadhaar, and ration card, but officials dismissed these, citing the absence of a birth certificate.

Sheikh was eventually brought back after his family approached Islam, who intervened with the central government and the BSF, leading to coordination with Bangladeshi authorities for his return.

Since then, the BJP in Maharashtra has intensified allegations that Bangladeshi nationals have illegally obtained birth certificates. Kirit Somaiya, a former MP from Mumbai’s eastern suburbs, sought data on birth certificate approvals in 2024 under the Right to Information act. He argued that Aadhaar cards tied to “fraudulently acquired” certificates should be cancelled. On October 13, he led a protest over an alleged “Bangladeshi birth certificate scam” near the police station where Dadamiya’s family was detained and called for a “combing operation” in Mumbai’s eastern suburbs.

Similar claims had surfaced during Delhi’s state election campaign earlier this year. BJP leaders had accused the then-ruling Aam Aadmi Party of facilitating Aadhaar cards for Bangladeshi immigrants and manipulating the city’s demography. Eventually, the BJP returned to power in Delhi after 25 years.

However, this pitch was cited as one of the reasons it failed to wrest control of Jharkhand state in last year’s elections. The election campaign for the eastern Indian state also featured claims from senior BJP leaders, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who made “illegal Bangladeshi immigration and infiltration” a major poll plank.

In campaign rallies, the chief ministers of Assam and Uttar Pradesh states, and Modi, all had accused the ruling Jharkhand Mukti Morcha party of “patronising infiltrators”. “If this continues, the tribal population in Jharkhand will shrink. This is a threat to tribal society and the country,” Modi had claimed. The Polis Project investigated and debunked these claims.

How a Broken Family Struggles to Survive

Since Dadamiya’s deportation, his wife Mariyam has taken on a second job sorting nuts for packaging at a small facility near her home, in addition to laboring as a domestic worker.

Even so, the family’s finances are precarious. They have to pay back a loan given by Dadamiya’s employer to admit Rehana to her preferred college to pursue higher studies. Hence, Mariyam can no longer afford to send Ayesha to after-school coaching classes.

Rehana has taken to pleading with people whom Dadamiya had lent money, like friends and neighbours, to pay them back. The family does not have the finances to challenge Dadamiya’s deportation legally.

“They had taken a loan of Rs. 45,000, of which Rs. 25,000 is still to be repaid. Until they do that, they cannot afford to go to court for Dadamiya,” said Limaye, who helped arrange for the loan.

Dadamiya’s daughters speak to him every day. Speaking about his condition, Ruksar said, “Papa is unable to find work there. No one will hire him there because he has no documents to show that he is Bangladeshi. He got work one day at a farm. At the end of the day, he was paid 200 taka.”

The girls have now applied for age, domicile, and nationality certificates from their local municipal corporation. They are eligible since Mariyam’s Indian citizenship is not in doubt. Mariyam had submitted her Aadhaar and PAN cards, as well as records of the land owned by her family in their native village, to the police. The land records, said a police official privy to the case, showed that Mariyam’s family had been living in India for several generations.

Dadamiya, however, had attempted to get a certificate for himself late last year when the police were rounding up other Bangladeshi nationals around him.

“Father thought that once he got the certificate he would be safe from deportation. But the lawyer he had approached said his birth certificate was not genuine so he gave up trying to get the document,” Rehana said.

Ruksar is hopeful the nationality certificates will enable her to see her father again. Until then, he is only a face on the screen.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.