Onus on Indian state for peace talks with Maoist party: Civil Society to President

Over 300 signatories from the civil society and prominent individuals have, in a memorandum to Indian President Draupadi Murmu, raised alarm over escalating counter-insurgency operations targeting the banned Maoist party, warning that these actions put Adivasi lives “under immediate and unprecedented threat.”

They asked the president, who is herself an Adivasi woman, to urgently initiate a shift “from conflict to dialogue” in regions where such operations are concentrated—Bastar in Chhattisgarh, Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, West Singhbhum in Jharkhand, and their adjoining areas.

No less than 400 individuals, including children and unarmed women and men, have lost their lives to police bullets and shrapnel over the last 16 months, in just the Bastar division of south Chhattisgarh, the memorandum said.

The operations intensified even as multiple Maoist party spokespersons have, of late, expressed their desire to engage in a peaceful dialogue, so that government forces may stop Operation Kagaar. The memorandum calls upon the President of India to advise her government to take a reflective break in its war on the people of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

The memorandum stated: “Most recently, Maoist representative Rupesh gave an interview stating that their cadres have been unilaterally instructed to observe a ceasefire. While the government has claimed openness to ‘unconditional’ dialogue, in practice, it has imposed preconditions—demanding surrender and return to the mainstream. These are not terms of negotiation; they are ultimatums.”

The signatories include retired professor of law G Haragopal, indigenous activist Soni Sori, advocate of incarcerated indigenous youth Bela Bhatia, rights activists Kavita Srivastava, Kranthi Chaitanya and Parminder Singh, among others.

On Friday, soon after news of the civil society appeal to President Murmu was out, a press release signed by the same spokesperson Rupesh, on a Maoist party letterhead, came into the public domain. It specifically asked for a month-long state ceasefire, ostensibly in response to the party’s earlier declaration of a unilateral ceasefire–except in the event of an adversary attack. “In spite of the likelihood of a resolution to the problem through peace talks, the government continues to attempt to resolve it through repression and violence,” the press note stated, referring to the military campaign over Karregutta, near the interstate border of Chhattisgarh and Telangana. However, the authenticity of this–the third printed statement of the party this month–remains to be ascertained.

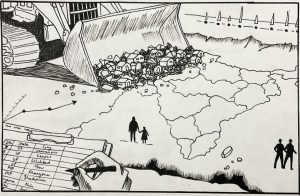

Operation Kagaar was launched at the turn of 2024, the monicker signalling the government’s intent to drive the Maoist cadres in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and neighbouring districts to the tipping point of either accepting a surrender out of a sense of despair or desperation caused by varied strongarm tactics, or extra-judicial killing in obscure counter-insurgent manoeuvres. No less than 400 individuals, including children and unarmed women and men, have lost their lives to police bullets and shrapnel over the last 16 months, in just the Bastar division of south Chhattisgarh, the civil society letter underlined.

What began as a hushed-up paramilitary operation at Karregutta–a range of hills at the southern edge of Bastar, bordering Telangana’s Mulugu district–has reportedly escalated over the past two days. An as-yet undetermined number of Maoist cadres are reported to have been encircled by as many as 10,000 to 20,000 counter-insurgency troops. This development has been corroborated by Inspector General (Bastar) P. Sundarraj’s recent statement and multiple media reports.

Aerial manoeuvres are also part of the operation, and bombing is not entirely ruled out. Drones are monitoring any possible Maoist attempt to break through the encirclement. The technology is also facilitating logistics for the state forces against the odds posed by guerrilla mobility within the forested hilly terrain, despite the green cover depleting in the summer months. The battle has fuelled human rights concerns even as state sources project it as a crushing blow to an insurgent battalion that could raise the pitch of the Maoist guerrilla war, from mere hit-and-run type of attacks to the level of mobile warfare, which involves greater manoeuvrability against adversary military attacks, particularly encirclements.

Intermittent firing was reported by sources for the fourth consecutive day on April 23, but the casualties are far too difficult to estimate at the moment, given the secretive conduct of the operations. Official sources put the body count at less than ten at the time of publishing this report. Actual losses suffered by the Maoists beyond their frontline are left to the imagination of state officials and the mainstream media.

The ongoing secretive operation appears to have been launched by central paramilitary forces, along with Chhattisgarh forces, with unverified reports suggesting that the Telangana Police was not fully briefed. Chhattisgarh Police handouts have also not confirmed key operational details. Likely, with a Congress-ruled Telangana government, the centrally ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which also administers Bastar, appears to have engaged local contingents only from the Chhattisgarh Police–STF, Bastar Fighters, and District Reserve Guards, in addition to the CRPF’s COBRA battalions, specialised in jungle warfare.

Several of these local contingents are known to have been constituted from among adivasis who surrendered to the state after years of volunteering with the Maoist People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army. The Indian state has used the Chhattisgarh policy of militarily organising adivasis against themselves, despite Supreme Court orders against the same. But the impact also spills over to sections of the civil society; the Bastariya Raj Morcha, floated less than a year ago by former communist leader Manish Kunjam, snatched the opportunity to lambast the Maoist party, politically, even when the latter had already begun executing a de facto ceasefire vis-à-vis its adversaries.

The operations at Karregutta come at a time when dissent against the paramilitary operations has spiked across Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, and multiple leaders of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) have come out with fresh statements suggesting they had already initiated a unilateral ceasefire, as a clear indication of their willingness to pursue peace talks. Conventions and mini demonstrations have been staged from Hyderabad to Visakhapatnam over the last few days to highlight the misuse of the armed might of the state on its indigenous citizens, and emphasise civilian deaths.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah, however, remains upbeat about his resolve to “wipe out” the Maoists by March 31, 2026, ringing alarm bells among a section of the critical intelligentsia and rights activists. After month-long deliberations among diverse civil society collectives from Telangana to Punjab, Kolkata to Delhi, and Chennai to Raipur, a campaign was launched on April 24 to press the authorities for a comprehensive ceasefire in the mineral-rich central and eastern states. Ceasefire is proposed as a confidence-building measure, and a necessary conducive environment, to pave the way for peace talks between the Indian government and the Maoist party.

Earlier this week, Rupesh, a second-rank spokesman of the proscribed party, speaking Hindi with a Telangana accent to Bastar Talkies, a local video channel, said his party had thoughtfully shelved its TCOC—Tactical Counter-Offensive Campaign—even in the face of a massive offensive under Operation Kagaar. Not resorting to a TCOC, at a time when the rebels’ adversary is at its aggressive zenith, clearly indicates a unilateral ceasefire. In the back-to-camera interview, the spokesman stressed that his call was an attempt to convey a vital decision, taken at the highest level of the party, to the larger public.

Following this, the rebels were permitted to resort to arms or explosives only when encircled or fired upon by state forces. This meant that the onus of achieving peace, through a reciprocative ceasefire, lay on Amit Shah’s armed forces, bound as they ought to be by the tenets of the Indian constitution and the rule of law. The civil society letter to the country’s President reflects this situation.

Rupesh’s call for peace was circulated in Hindi and Telugu. Following his oral and textual calls, the People’s Liberation Guerilla Army, a military formation of the Maoist party, formed two decades ago and overwhelmingly comprising indigenous people hailing from Bastar, Kolhan and the Chhota Nagpur Plateau–would, by and large, have silenced its guns, rifles, and IEDs. The second-rank spokesman’s first appeal for a ceasefire to facilitate peace talks came a week after Abhay, a Maoist central committee spokesman, published a statement, in Telugu, lauding civil society initiatives for peace talks between his party and government representatives.

The state forces in both Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh have, nevertheless, continued killing people. They also killed unarmed Maoists, like the middle-aged writer Renuka; she was reportedly killed in cold blood earlier in April while she was resting all alone in a hut. Previously, Chelapathy, a veteran organiser, was killed along with his accompanying comrades while recovering from an illness.

Soni Sori, Bela Bhatia, and roving activists like Himanshu Kumar have repeatedly foregrounded and condemned the atrocities committed by government forces on the indigenous local populace in Bastar under the guise of combatting Maoist rebels. The rebels, however, seemed to have integrated themselves and identified with the deprived and dispossessed in their struggle for land, forests, water and dignity (jal, jungle, zameen aur izzat). Concerted attempts through multi-pronged strategies to wean away the local populace from the Maoist cadre may have, over the last decade and a half of intensive counter-insurgency operations, created a tangible dent in their bonds. Nonetheless, Rupesh was categorical in his allusion to the hyperbolic assertions of the Union Home Minister, who set a specific date for ending the insurgency.

Amidst the concerning extent of the casualties and the utter disarray in the lives of the local inhabitants, as widely reported, the civil society initiative for peace talks could offer the promise of a timely resolution of the fundamental issues that may have triggered the rebellious movement led by the CPI (Maoist).

Related Posts

Onus on Indian state for peace talks with Maoist party: Civil Society to President

Over 300 signatories from the civil society and prominent individuals have, in a memorandum to Indian President Draupadi Murmu, raised alarm over escalating counter-insurgency operations targeting the banned Maoist party, warning that these actions put Adivasi lives “under immediate and unprecedented threat.”

They asked the president, who is herself an Adivasi woman, to urgently initiate a shift “from conflict to dialogue” in regions where such operations are concentrated—Bastar in Chhattisgarh, Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, West Singhbhum in Jharkhand, and their adjoining areas.

No less than 400 individuals, including children and unarmed women and men, have lost their lives to police bullets and shrapnel over the last 16 months, in just the Bastar division of south Chhattisgarh, the memorandum said.

The operations intensified even as multiple Maoist party spokespersons have, of late, expressed their desire to engage in a peaceful dialogue, so that government forces may stop Operation Kagaar. The memorandum calls upon the President of India to advise her government to take a reflective break in its war on the people of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh.

The memorandum stated: “Most recently, Maoist representative Rupesh gave an interview stating that their cadres have been unilaterally instructed to observe a ceasefire. While the government has claimed openness to ‘unconditional’ dialogue, in practice, it has imposed preconditions—demanding surrender and return to the mainstream. These are not terms of negotiation; they are ultimatums.”

The signatories include retired professor of law G Haragopal, indigenous activist Soni Sori, advocate of incarcerated indigenous youth Bela Bhatia, rights activists Kavita Srivastava, Kranthi Chaitanya and Parminder Singh, among others.

On Friday, soon after news of the civil society appeal to President Murmu was out, a press release signed by the same spokesperson Rupesh, on a Maoist party letterhead, came into the public domain. It specifically asked for a month-long state ceasefire, ostensibly in response to the party’s earlier declaration of a unilateral ceasefire–except in the event of an adversary attack. “In spite of the likelihood of a resolution to the problem through peace talks, the government continues to attempt to resolve it through repression and violence,” the press note stated, referring to the military campaign over Karregutta, near the interstate border of Chhattisgarh and Telangana. However, the authenticity of this–the third printed statement of the party this month–remains to be ascertained.

Operation Kagaar was launched at the turn of 2024, the monicker signalling the government’s intent to drive the Maoist cadres in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and neighbouring districts to the tipping point of either accepting a surrender out of a sense of despair or desperation caused by varied strongarm tactics, or extra-judicial killing in obscure counter-insurgent manoeuvres. No less than 400 individuals, including children and unarmed women and men, have lost their lives to police bullets and shrapnel over the last 16 months, in just the Bastar division of south Chhattisgarh, the civil society letter underlined.

What began as a hushed-up paramilitary operation at Karregutta–a range of hills at the southern edge of Bastar, bordering Telangana’s Mulugu district–has reportedly escalated over the past two days. An as-yet undetermined number of Maoist cadres are reported to have been encircled by as many as 10,000 to 20,000 counter-insurgency troops. This development has been corroborated by Inspector General (Bastar) P. Sundarraj’s recent statement and multiple media reports.

Aerial manoeuvres are also part of the operation, and bombing is not entirely ruled out. Drones are monitoring any possible Maoist attempt to break through the encirclement. The technology is also facilitating logistics for the state forces against the odds posed by guerrilla mobility within the forested hilly terrain, despite the green cover depleting in the summer months. The battle has fuelled human rights concerns even as state sources project it as a crushing blow to an insurgent battalion that could raise the pitch of the Maoist guerrilla war, from mere hit-and-run type of attacks to the level of mobile warfare, which involves greater manoeuvrability against adversary military attacks, particularly encirclements.

Intermittent firing was reported by sources for the fourth consecutive day on April 23, but the casualties are far too difficult to estimate at the moment, given the secretive conduct of the operations. Official sources put the body count at less than ten at the time of publishing this report. Actual losses suffered by the Maoists beyond their frontline are left to the imagination of state officials and the mainstream media.

The ongoing secretive operation appears to have been launched by central paramilitary forces, along with Chhattisgarh forces, with unverified reports suggesting that the Telangana Police was not fully briefed. Chhattisgarh Police handouts have also not confirmed key operational details. Likely, with a Congress-ruled Telangana government, the centrally ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which also administers Bastar, appears to have engaged local contingents only from the Chhattisgarh Police–STF, Bastar Fighters, and District Reserve Guards, in addition to the CRPF’s COBRA battalions, specialised in jungle warfare.

Several of these local contingents are known to have been constituted from among adivasis who surrendered to the state after years of volunteering with the Maoist People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army. The Indian state has used the Chhattisgarh policy of militarily organising adivasis against themselves, despite Supreme Court orders against the same. But the impact also spills over to sections of the civil society; the Bastariya Raj Morcha, floated less than a year ago by former communist leader Manish Kunjam, snatched the opportunity to lambast the Maoist party, politically, even when the latter had already begun executing a de facto ceasefire vis-à-vis its adversaries.

The operations at Karregutta come at a time when dissent against the paramilitary operations has spiked across Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, and multiple leaders of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) have come out with fresh statements suggesting they had already initiated a unilateral ceasefire, as a clear indication of their willingness to pursue peace talks. Conventions and mini demonstrations have been staged from Hyderabad to Visakhapatnam over the last few days to highlight the misuse of the armed might of the state on its indigenous citizens, and emphasise civilian deaths.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah, however, remains upbeat about his resolve to “wipe out” the Maoists by March 31, 2026, ringing alarm bells among a section of the critical intelligentsia and rights activists. After month-long deliberations among diverse civil society collectives from Telangana to Punjab, Kolkata to Delhi, and Chennai to Raipur, a campaign was launched on April 24 to press the authorities for a comprehensive ceasefire in the mineral-rich central and eastern states. Ceasefire is proposed as a confidence-building measure, and a necessary conducive environment, to pave the way for peace talks between the Indian government and the Maoist party.

Earlier this week, Rupesh, a second-rank spokesman of the proscribed party, speaking Hindi with a Telangana accent to Bastar Talkies, a local video channel, said his party had thoughtfully shelved its TCOC—Tactical Counter-Offensive Campaign—even in the face of a massive offensive under Operation Kagaar. Not resorting to a TCOC, at a time when the rebels’ adversary is at its aggressive zenith, clearly indicates a unilateral ceasefire. In the back-to-camera interview, the spokesman stressed that his call was an attempt to convey a vital decision, taken at the highest level of the party, to the larger public.

Following this, the rebels were permitted to resort to arms or explosives only when encircled or fired upon by state forces. This meant that the onus of achieving peace, through a reciprocative ceasefire, lay on Amit Shah’s armed forces, bound as they ought to be by the tenets of the Indian constitution and the rule of law. The civil society letter to the country’s President reflects this situation.

Rupesh’s call for peace was circulated in Hindi and Telugu. Following his oral and textual calls, the People’s Liberation Guerilla Army, a military formation of the Maoist party, formed two decades ago and overwhelmingly comprising indigenous people hailing from Bastar, Kolhan and the Chhota Nagpur Plateau–would, by and large, have silenced its guns, rifles, and IEDs. The second-rank spokesman’s first appeal for a ceasefire to facilitate peace talks came a week after Abhay, a Maoist central committee spokesman, published a statement, in Telugu, lauding civil society initiatives for peace talks between his party and government representatives.

The state forces in both Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh have, nevertheless, continued killing people. They also killed unarmed Maoists, like the middle-aged writer Renuka; she was reportedly killed in cold blood earlier in April while she was resting all alone in a hut. Previously, Chelapathy, a veteran organiser, was killed along with his accompanying comrades while recovering from an illness.

Soni Sori, Bela Bhatia, and roving activists like Himanshu Kumar have repeatedly foregrounded and condemned the atrocities committed by government forces on the indigenous local populace in Bastar under the guise of combatting Maoist rebels. The rebels, however, seemed to have integrated themselves and identified with the deprived and dispossessed in their struggle for land, forests, water and dignity (jal, jungle, zameen aur izzat). Concerted attempts through multi-pronged strategies to wean away the local populace from the Maoist cadre may have, over the last decade and a half of intensive counter-insurgency operations, created a tangible dent in their bonds. Nonetheless, Rupesh was categorical in his allusion to the hyperbolic assertions of the Union Home Minister, who set a specific date for ending the insurgency.

Amidst the concerning extent of the casualties and the utter disarray in the lives of the local inhabitants, as widely reported, the civil society initiative for peace talks could offer the promise of a timely resolution of the fundamental issues that may have triggered the rebellious movement led by the CPI (Maoist).

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.