Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story: Transforming Taboo Into Reflection and Resistance

On September 16, 2022, the film Matto Ki Cycle was released in Indian cinemas under the banner of Prakash Jha Productions. It was based on Matto (Jha), who supports his wife and two young daughters by cycling daily to the city as a construction laborer. It was written and directed by M. Gani, who hails from Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Before it hit screens, however, Matto Ki Cycle‘s story was first staged at the auditorium of Hybrid Public School in Mathura, under the title “Cycle” and directed by Sanif Madar.

For Gani, staging a story is the first crucial step in his storytelling process. He feels that the lack of quality plays in contemporary Hindi literature has motivated him to present film scripts on stage first. Gani’s latest story, which he aspires to turn into a film, is subtly political. It has Muslim protagonists and deals with a taboo theme like male infertility.

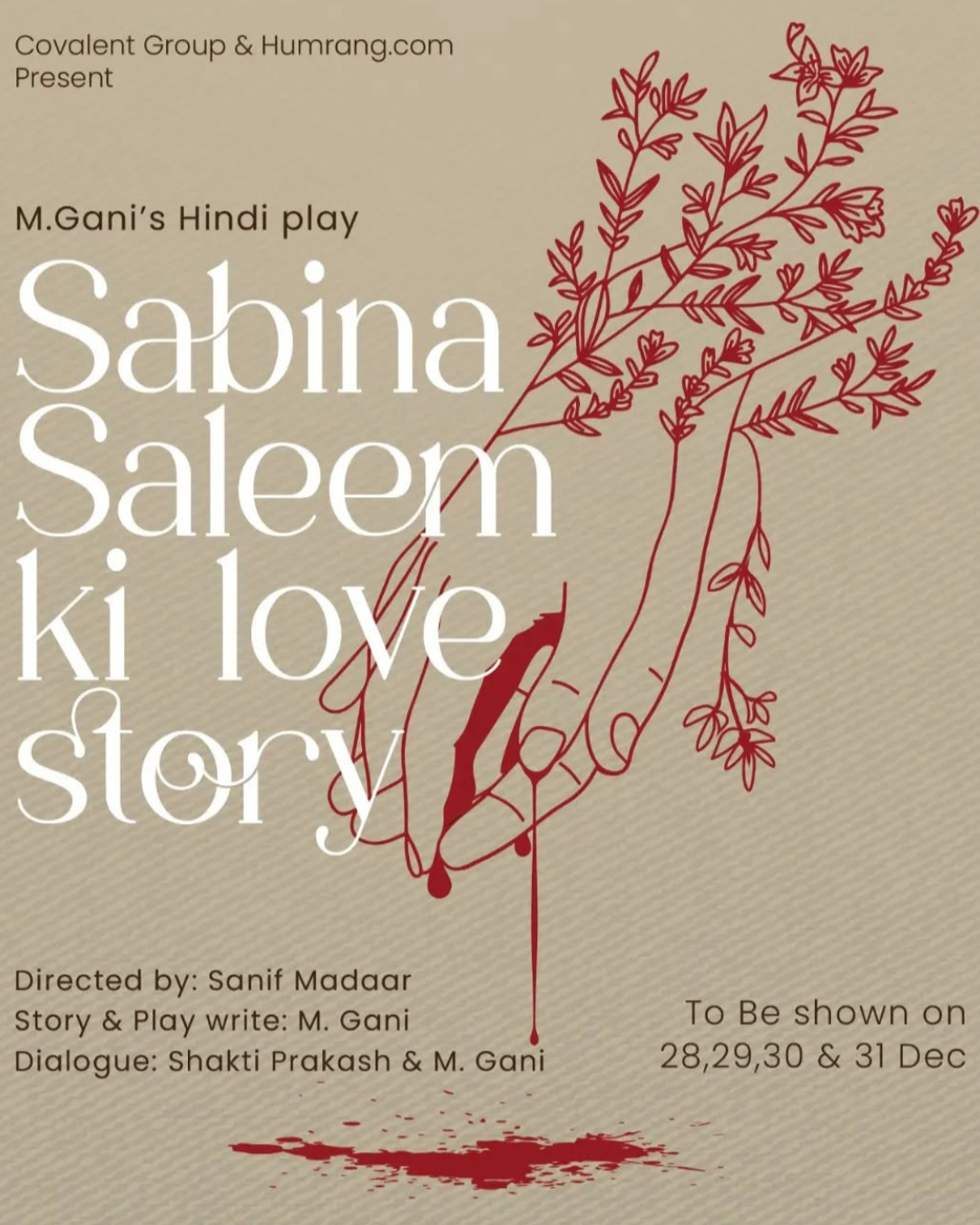

This narrative, combined with concerns of commercial viability, has made it difficult to find a producer. In the meantime, however, it was staged from December 28 to 31, 2024, at the studio auditorium of Hybrid Public School under Madar’s direction, as a play titled Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story.

The play is a poignant drama, centered on a couple. While Sabina has long been blamed for not conceiving, it is eventually revealed that Saleem is infertile, a truth he neither accepts nor shares. Their lives unfold through a series of dramatic moments, each offering a layered reflection of society.

Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story is a powerful exploration of gender and patriarchy, foregrounding the denial of autonomy to women, the weight of societal expectations, and the struggle for individual identity. The story also touches upon class and religious identity, communal tensions, and how love endures, transforms, and transcends in restrictive social structures.

Contemporary India has witnessed a catastrophic escalation in targeted violence against Muslims. According to a 2024 report by the India Hate Lab, an alarming 98.5% of documented hate speech incidents were directed at the Muslim community. This entrenched majoritarianism fosters a climate of fear, engendering widespread self-censorship and curtailing the exercise of constitutional freedoms.

Performed in Mathura—a city imbued with Hindu religious symbolism as the birthplace of Lord Krishna, and marked by limited functional infrastructural support for the arts, and minimal access to institutionalized cultural capital—the play challenges the dominant narratives of exclusion. It becomes a form of cultural resistance and subaltern expression, reclaiming public space to assert the principles of secularism, constitutional rights, and equal citizenship in an increasingly polarized society.

Within this socio-political milieu characterized by Islamophobia, structural violence, and hegemonic patriarchy, thought-provoking theater that ignites dialogue around subjects buried under silence and shame, transforms taboo into reflection and resistance. The staging of Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story is, without a doubt, a radical cultural act.

Muslim Identity, Masculinity, and Margins

The stage is lit, revealing a room with a bed, a window, and a kitchen. From behind the audience, Saleem (Saurabh Khare) runs onto the stage and begins dancing with Sabina (Ashiya Madar). Interrupting the dancing, Sabina calls, “Zakir ke chacha… O Zakir ke chacha” (Zakir’s uncle..O Zakir’s Uncle). Startled, Saleem wakes up to realize that the dance was just a dream. In reality, he lacks the courage to express his desire to dance with Sabina.

Saleem is a factory worker by profession and a Muslim by faith. He is physically slight, shy, soft-spoken, unfailingly gentle, and never raises his voice. He does not fit into the conventional patriarchal definition of masculinity, making him a reserved person for others, but he deeply loves his wife, Sabina.

To bring such an unconventional character to life, Khare had to distance himself from familiar representations of masculinity. Saleem’s softness and emotional vulnerability required a different approach. Saurabh adjusted his physicality to appear less confident, adopting a subdued presence on stage to express Saleem authentically.

“I drew inspiration for this character from the protagonist Eeda in Hanif Madar’s story Eeda,” Gani told me, referring to a figure often dismissed by society as naive because they aren’t “masculine” enough. “In society, people often perceive individuals like Saleem as foolish, but to me, such people are pure, gentle, and lovable. Through films, plays, and stories, I express what I feel and what I wish to see in society.”

Saleem’s gender identity is overshadowed when others perceive him primarily through his religious identity. His image as a gentle, non-threatening man collapses the moment his Muslim identity comes to the fore during Hindu-Muslim riots. His Hindu friend, Mukhiya (Harshit Kashyap), once a brotherly figure to Saleem, loses his son Gaurav (Hariom Chautala) in the riots. When Saleem offers condolences at the cremation ground, Mukhiya silently turns away. That unreturned gaze denies Saleem the space to grieve, his identity outweighing his sorrow.

At this point in the play, communal riots are not loud disruptions alone: they linger as quiet distances, reshaping the emotional geographies between people. M. Gani experienced in his own life, “a silence [that] fell between our family and a family friend.” He was not simply recounting an incident, but revealing how riots seep into the unsaid, turning once-familiar bonds into unfamiliar silences, where affection hesitates and familiarity recoils. The play resonates with this ache, showing how relationships, once grounded in trust, begin to falter under the weight of communal fault lines.

Everyday Feminism in Narrow Rooms

The major women in Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story are the titular protagonist, Sabina, her husband’s sister, Agre Wali Aapa (Anita Chaudhary), a woman in her 40s, spends most of her time at Saleem’s house, as her own adult children do not treat her well and often find her presence bothersome. She frequently taunts Sabina about not having children. Meanwhile, Shalu (Lalitesh Prajapati), an 18-year-old senior secondary school student from the neighborhood, is Sabina’s best friend. Each of them embodies a powerful expression of feminist rage while revealing the deep vulnerabilities imposed by patriarchy. Their journeys not only shape the narrative but also highlight diverse experiences of womanhood and resistance.

Sabina is fiercer, more pragmatic, and more straightforward than her husband. Sabina never wanted to marry Saleem, and consequently never reciprocated his love, maintaining an emotional distance from him. It’s her way of resistance in a marriage she never chose for herself. In several key moments, she upholds her autonomy, whether standing up to Shalu’s parents’ anger, confronting local goons, or deciding to stop cooking on days she didn’t want to. To bring her character to life, Aashiya engaged in practices such as writing a biography for Sabina. Sabina earns her own money by stitching men’s clothes, asserting her financial independence.

In a society quick to blame women for infertility and punish them for speaking, Sabina bears the brunt of that stigma. Her vulnerability, shaped by patriarchy and lower-class status, forced her into a life with Saleem, and later into carrying the label of baanjh (infertile woman).

The play keenly highlights the linguistic violence inflicted upon women. Agra Wali Aapa, Sabina’s sister-in-law, is a woman in her 40s who spends much of her time at Saleem’s house. She is never called by her real name, only called “Agra Wali Aapa.”

This casual erasure reflects a deeper societal disregard for women’s identities. The refusal to acknowledge her by name symbolizes how her individuality is deemed insignificant. Like Sabina, she too was married against her will, another reminder of the many ways in which women’s choices and identities are suppressed.

Eighteen-year-old Shalu wanted to marry the man she loved, but her family disapproved. In defiance, she eloped, an act that provoked an attempted honour killing by her own kin. According to the latest data from the National Crime Records Bureau, India reported 25 cases of honour killings in both 2019 and 2020, and 33 in 2021. However, many cases go unreported.

Despite leading different lives, crimes against women reveal how women’s autonomy is constantly suppressed first within the family, then by larger forces like gender stereotypes, community discrimination, and social biases. Yet these three characters establish their own version of feminism with the smallest acts of defiance—be it earning a livelihood, rejecting forced love, or eloping—which become powerful assertions of selfhood.

These everyday resistances form a grounded, lived feminism shaped by constraint and courage.

Love, Art, and Politics

Sabina, unable to conceive, endures taunts and resorts to taking all kinds of medicines from doctors and traditional healers. However, the central turning point in the play occurs when Saleem discovers that he is the infertile one.

Even after learning about his low sperm count, Saleem initially cannot bring himself to tell Sabina. When he finally does, his reaction is completely unlike his usual personality; he takes an extreme step of hitting her in a way that leaves the audience in shock.

Male infertility is a common medical condition, yet discussions around it are absent from both education and everyday conversations. Saleem’s reaction effectively highlights how patriarchy also impacts men. It calls for a space where men’s vulnerabilities and difficult experiences, such as with infertility, can be acknowledged and processed with empathy and openness.

However, in reality, the burden of infertility is unfairly placed on women even in cases where medical evidence suggests otherwise. According to a report from the National Library of Medicine, “Since male and female factors often coexist, it is essential that both partners are evaluated and managed together. Overall, male factors significantly contribute to approximately 50% of all infertility cases.” Lack of sex education and open dialogue about male reproductive health leads to male ego bruising, avoidance of proper treatment, and increased control over one’s wife.

The play also explores the many shades of love, romance, and vulnerability. Saleem finds joy in simply loving Sabina, even when his feelings go unreciprocated. But after a turning point in their relationship when Saleem fears losing her, Sabina slowly begins to reciprocate. His quiet devotion and vulnerability awaken her feelings, drawing them closer in an emotional connection.

Meanwhile, Mukhiya, who had distanced himself from Saleem, reconciles with him by the play’s end.

Theater artist M. Sanif Madar has long been staging plays in Mathura, such as Sukhiya Mar Gaya Bhookh Se (2018), B-Three (2019), and Cycle (2016), all centered on social issues. With Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story, he has, for the first time, ventured into the world of romance. Staging and watching romantic plays may be common in metropolitan cities like Delhi and Mumbai. However, in a city like Mathura, it is a bold and risky endeavor, as audience reactions or even those from outsiders could turn violent.

In her 1999 book All About Love: New Visions, author bell hooks posits that lovelessness is a “wound” that needs to be addressed, not just as a personal problem but as a collective societal issue. She also mentions how lovelessness fuels various types of negativity, including violence. To counteract this and remind people of love’s transformative power, art must demonstrate its beauty.

Sanif Madar chose Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story over well-known romantic plays because he was seeking something that moved beyond traditional narratives. In Mathura, he observed that most love stories staged for audiences tend to feel crude or superficial, lacking emotional depth. “I wanted to bring a love story that truly touches people’s hearts,” he shared.

This play was staged not only to evoke that beautiful emotion, but also to reflect on how love itself is often strained and impacted by the harsh realities of society: a truth that must be equally acknowledged.

The play is layered with characters who, like in real life, are neither entirely right nor entirely wrong. While it tells a love story on the surface, it also powerfully reveals how, in a patriarchal and heterosexual society, the ability to love and the right to be loved are unevenly distributed and met with certain statuses.

The play was attended by over 50 people each day, including writers, filmmakers, scientists, and professionals from the development sector. Among them was Dinesh Khanna, former director of NSD and Bhartendu Natya Academy, who noted that while the play’s montage-like structure made it complex, it reflected the layered nature of life itself. He found it deeply moving for its engagement with important issues.

State of Theater in Tier-3 Cities Like Mathura

Mathura has long been a hub of performing arts, known for its vibrant traditions of Raas, Nautanki, Bhagat styles and Rasleela. However, these art forms are mostly performed during specific occasions like Krishna Janmashtami, Radha Ashtami, or festivals such as Taj Mahotsav. While skits and performances can still be seen in Mathura-Vrindavan temples, or the private spaces of saints, regular performances or those that center social issues remain rare.

Despite its rich legacy, the city lacks the recognition and support needed to develop its performing arts, from infrastructure to access to knowledge. While some infrastructure has emerged in Mathura, it still falls short of the standards in more metropolitan centers. On off days, art spaces are often repurposed for alternative uses, like accommodating vegetable vendors, reflecting a lack of dedicated focus on the arts.

Theater artist and professor at BSA College, Mathura, Dr. Vijay, shared his insights, noting that in India, art forms like classical music, dance, instrumental performance, and theater often struggle for recognition because education is almost exclusively seen as a pathway to secure employment. Theater, in particular, is seldom considered a viable career option, leading to limited awareness and slow development, especially in smaller cities like Mathura.

Manisha Gupta, a Mumbai-based actress originally from Unnao, Uttar Pradesh, reflected on the state of theater in her hometown. She noted that children have little to no exposure to theater, and the few active groups seldom make efforts to involve or educate the youth.

Abhishek Kumar, an actor and theatrist from Mumbai, hailing from Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh, where theater began around 1914, shared, “At present, amateur theater continues, but there are neither sufficient resources nor adequate financial support available for artists to pursue it as a profession.” He also mentioned the lack of training schools or repertory companies to nurture and advance theater in these regions.

Despite the absence of institutional support, limited infrastructure, and the complex socio-political realities that define tier-3 cities, some artists still hold onto their art forms with fierce dedication. In places where performing arts often struggle to find space, time, and audiences, the unshakable passion of these theater-makers keeps the art form breathing.

Sabina Saleem Ki Love Story doesn’t just stage a play, it is the offering of those who, against all odds, continue to nurture justice, empathy, and dialogue through theater. In their commitment, the stage in these cities continues to pulse with life. Through them, theater breathes quietly, insistently, defiantly, even in places where it is expected to disappear.