“In this wide, wide world, man is not alone;

Beasts and birds, flowers and trees are there.”

— Umashankar Joshi (Tr. Dushyant Pandya) / from Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt.

Some of the earliest recorded art in the world, like the cave paintings of Chauvet and Lascaux in southwestern France, Egyptian frescoes and hieroglyphs, and sculptural remnants from the Indus Valley Civilization, are also perhaps the first-ever glimmers of the innate human need to express ourselves through art. These prehistoric artworks on cave interiors and clay moldings, which allow us to peek into our ancestors’ minds as primitive artists, are akin to modern journaling methods.

For all artists, encounters with the world—its people and nature—are sources of great inspiration and learning. And it is in the journal, the notebooks, and the diaries where these varied experiences collide and find expression. In holding space for the deepest or the most transient thoughts, the artist’s diaries are also the most private artworks.

Part journals, part sketchbooks, artist diaries—unless displayed at exhibitions or reproduced in new formats like published matter or films—remain unseen, unheard of, and stowed away in private collections. Or worse, lost to oblivion.

From Leonardo Da Vinci to Frida Kahlo to Keith Haring, artists across generations and geographies remain connected via their tradition of keeping notebooks. Many of these have recently been digitized and can now be accessed online.

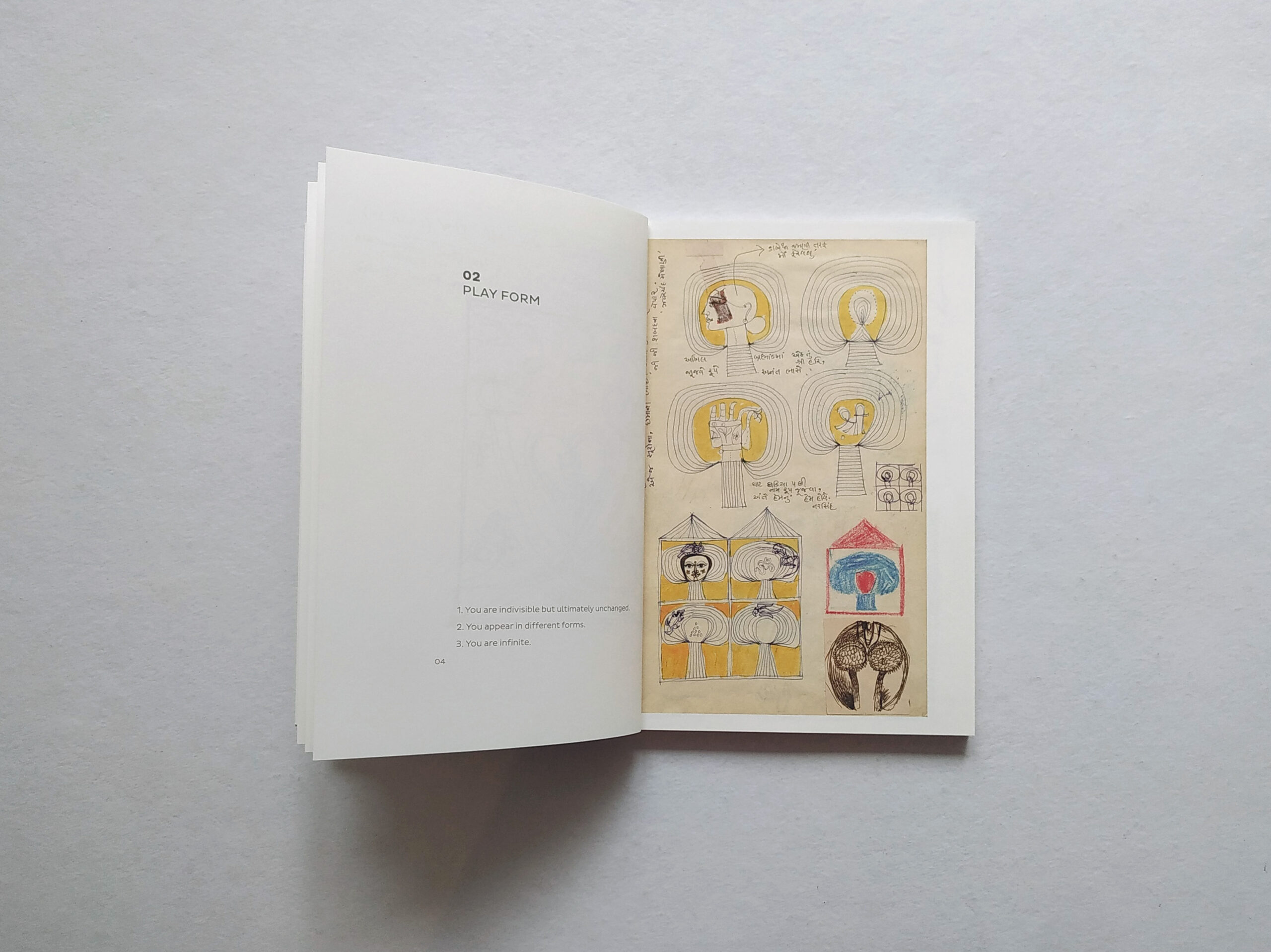

With this intention of preserving and reviving what the artist’s notebooks hold, visual artist Vishwa Shroff and writer-curator Veeranganakumari Solanki first approached the expansive archive of multidisciplinary artist and educator Jyoti Bhatt, who turned 90 last year. Known primarily for his photographs, Bhatt also has among his collections notebooks—or “sketchbooks,” as he refers to them—carefully preserved over five decades between the 1950s and 2000.

“It is believed in our country that if a person leaves this world without completing his or her wishes, his soul does not get peace,” Bhatt wrote to me over a text message. “I have a fairly large number of ideas for paintings and graphic prints, which are incomplete.”

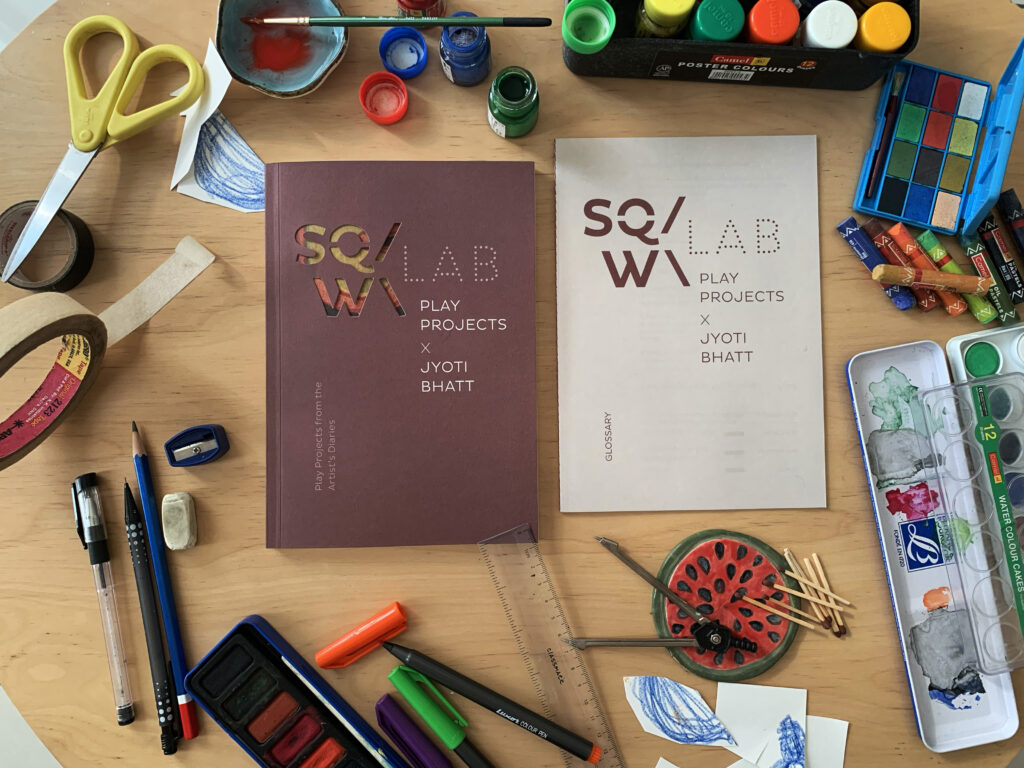

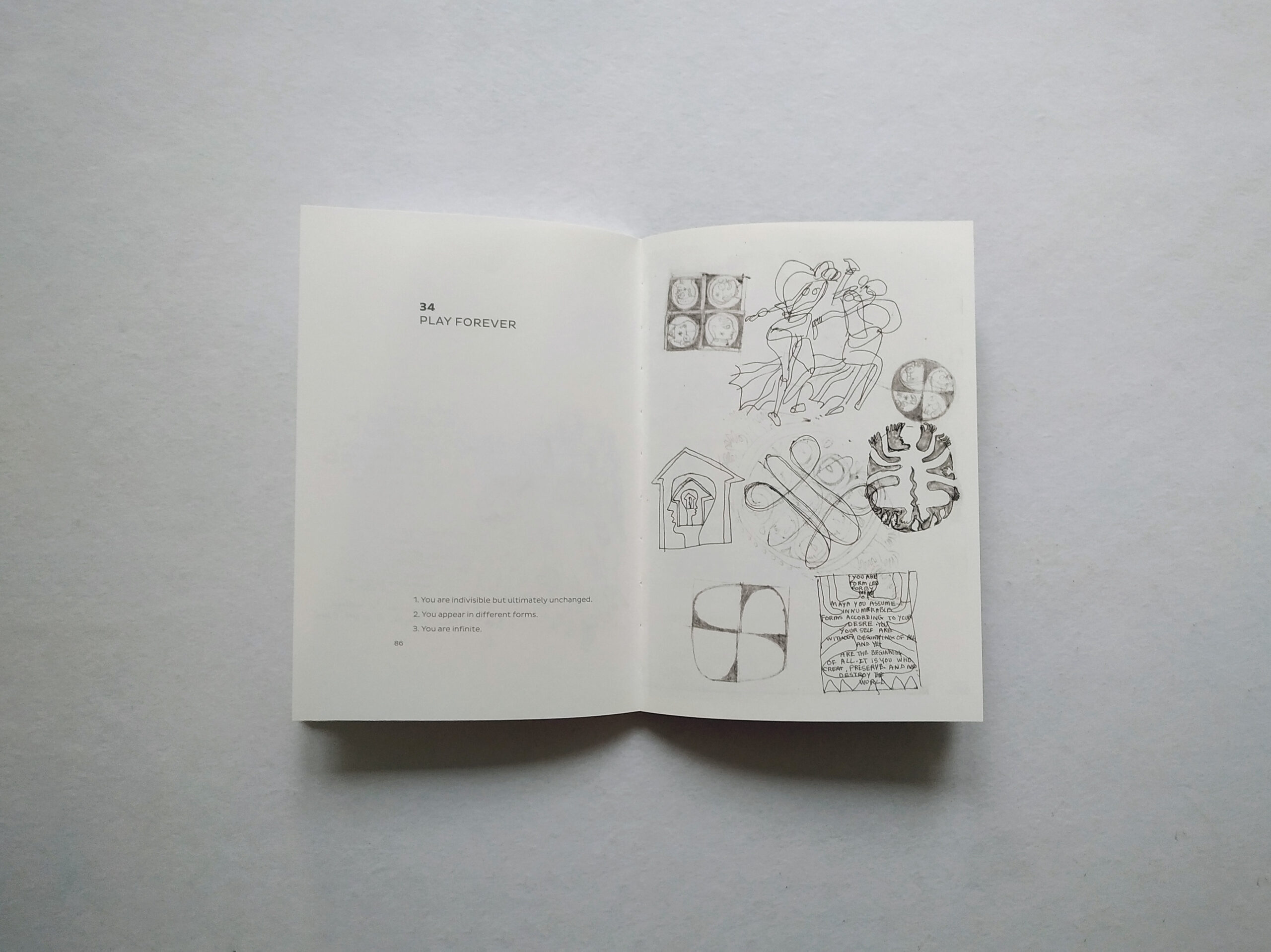

Shroff and Solanki took 48 of these ideas—drawings, poems, puzzles, and thoughts from his sketchbooks, shortlisted by Bhatt—and further edited them to 35. These eventually became Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt, the book that launched in August 2024 in Mumbai and Bhatt’s hometown of Vadodara in September of that year.

It is a premier publication by SqW: Lab, Mumbai, a cultural fellowship program founded by Shroff, her partner architect Katsushi Goto, and curator Charlie Levine for art practitioners worldwide. Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt is thoughtfully designed by Studio Anugraha as a set of two slim volumes: one, a main book, and the second, a glossary, held together with a paper band.

The Making and Function of Play Projects

Resisting the urge to create yet another book that simply catalogs Bhatt’s work, Play Projects’ philosophy was based on artist Hans Ulrich Obrist’s “Do It!” series. Here, artists are invited to explore ideas through prompts and set rules, creating work in new collaborative ways. As the artist’s niece and guardian of his archive, Shroff had a free hand to work on the book. The team built on what emerged, with the main book evolving as an interactive exercise format.

The index-as-word-play was inspired by novelist and filmmaker Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. Within Bhatt’s work sits one page and a set of instructions and rules on the other, encouraging readers to create their own art while retaining the core idea of play.

The glossary pushes the boundaries of definition, containing more than just references and translations supporting the main booklet. “We felt it needed an extra intervention to become a trigger for someone else to think about their own work, rather than it remaining Jyoti Bhai’s,” Shroff asserted.

Piyush Thakkar, translator of Bhatt’s richly layered notes written in Gujarati, advised the team to cite Bhatt’s original sources, “completing it” in a way that helps the glossary become something hinged to the book, while also holding its own. This extra intervention ensures that the glossary not only translates but also cites the original source of a few lines that Bhatt might have jotted down in his notebook. This way, the reader understands the lines but is also led to the source, the entire poem, and the author.

Shroff fondly recalled how her childhood interactions with Bhatt were always about learning, be it an introduction to classical music, books, or solving puzzles. For Shroff, as for the scores of students Bhatt taught during his extensive tenure as faculty at the Fine Arts Department at the Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU), Baroda, he will always be, “more than anything else, a teacher.”

Solanki’s initial interactions were similar. “I still remember that once I was at his studio and he had a student upstairs making drawings inspired by one of Bhatt’s diaries,” she reminisced. “In the meantime, he [Bhatt] was trying to crack another math puzzle downstairs on his table, which he was also looking at from one of his own diaries.”

Artist journals also become wonderful sources of knowledge and education, often for other artists, since what goes into making the final artwork is rarely accessible. Speaking of Play Projects, Bhatt echoed this sentiment. “This book allows other art practitioners to use my sketches as inspiration for their own work,” he said, “which is very rewarding for me to see.”

Jerry Pinto and The Notebook As A Reflection of Chaos

Someone who journaled as prolifically and dedicatedly is the abstractionist Mehlli Gobhai, whose diaries became a part of his treasured art estate on his passing in 2018. For the poet, writer, and translator Jerry Pinto, those diaries were special, as “they were nets that Mehlli cast into the sea around him, the sea of thought, the sea of imagination, the sea of inspiration, the sea of motivation.”

From noting down lines gleaned from books and magazines on art so they became a part of his zehn (subconcious) to sketches of the hijras (transgenders) he observed en route to his orchard home in Gholvad to his thoughts and sketches for future works, Gobhai’s notebooks are a boundless confluence of richness and depth. “The function of the notebook is to indicate to us that what we actually are is chaos,” Pinto expressed. “But the chanchal (whimsical/meandering) mind often happens upon jewels, happens upon pearls of wisdom, and then it is time to stop and actually grasp at that pearl.”

Pinto viewed the making and keeping of the notebook as the way that “the pearl has to be grasped at that moment, because it is part of your journey into a self and past, the self into the many multiple selves that are waiting for you,” he said. “And those notebooks, each page of the notebook, are like the logbook, or the archive, or the black box of a journey.”

These journeys often lead to other journeys, ones only a few might be privy to.

Mira Nair On Her Films’ Look-Books

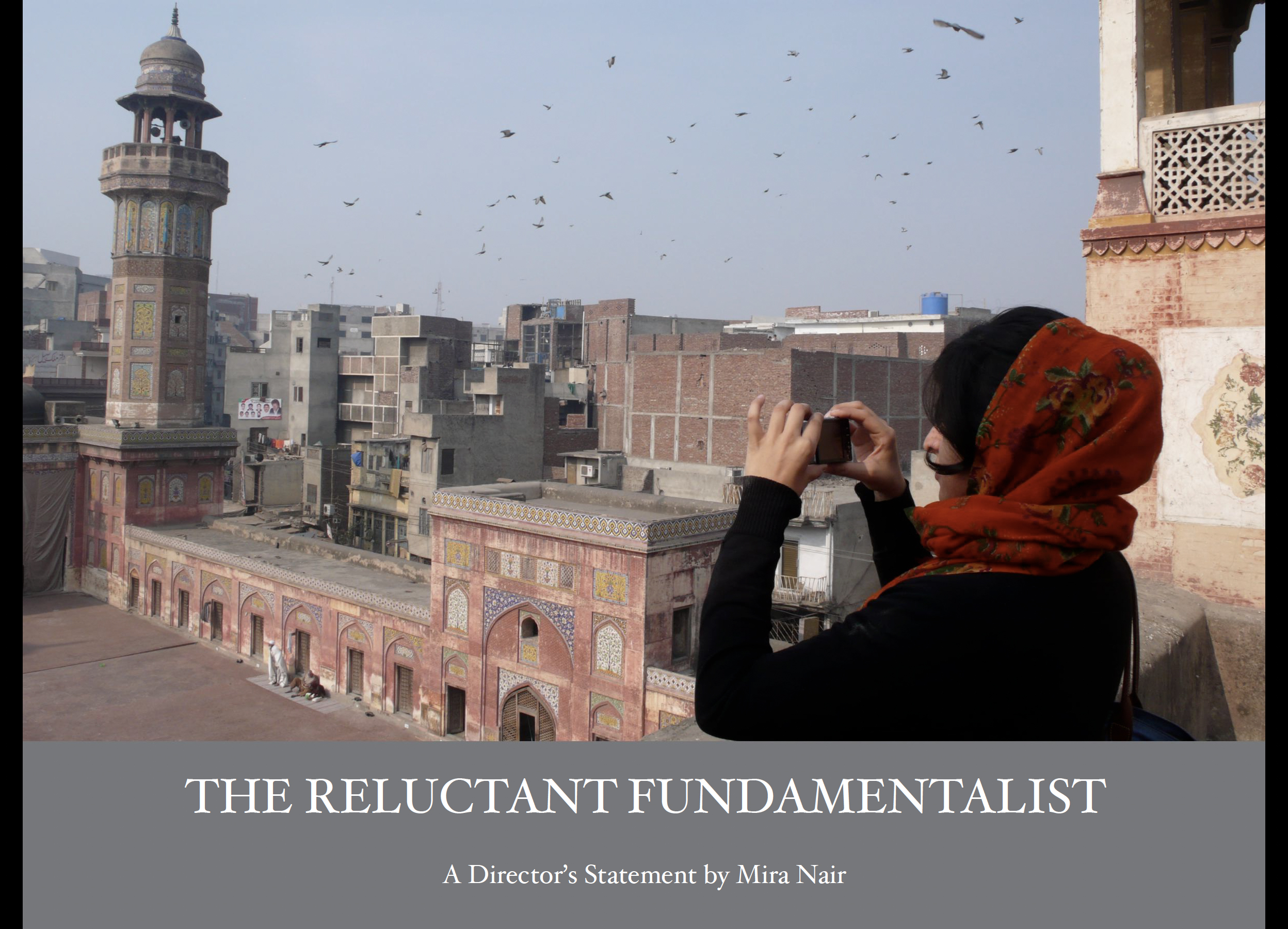

When filmmaker Mira Nair first traveled to Lahore—“the land of my father,” as she shared—she felt deeply stirred. So much so that when her friend, musician Ali Sethi, brought her the manuscript of Mohsin Hamid’s 2007 novel The Reluctant Fundamentalist, she knew immediately that she had to adapt it cinematically.

As a practice, Nair makes a look-book with references from different visual arts for all her films, “so that the aesthetic and philosophy of the film is understood by all making it with me,” she shared. For The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Nair kept a journal to record her thoughts and process. “I believe I have been put on this earth to tell stories of living between worlds,” she said.

Akin to visual journals, Nair’s lookbooks direct the feel and the sense one experiences when viewing her movies. “My visual influences are vast and eclectic,” she explained, “from the jewel colors of the great painter Amrita Sher-gil to the graphic geometry of urban landscapes photographed by Andreas Gursky to the avant-garde architectural vision of my dear friends Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio. I am interested in creating a new visual language for the phenomenon of globalization, which forces the energy of order and chaos to be viewed in the same frame.”

A tactile memory of silks and zardozi (gold embroidery) in marigold oranges and earthy reds from Nair’s Monsoon Wedding (2001) blooms in the recesses of one’s mind, morphing into the delicate translucence of jamdanis (fine hand-woven textiles) and tant cottons of her shifting worlds in The Namesake (2006). Quite like the holographic airport posters seen in the latter, which are a part of Travelogues, a permanent public artwork by design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro, installed at the international arrivals terminal at the John F. Kennedy Airport in New York.

Aradhana Seth: A Merchant of Images

The opposite of this—where a work of art created specifically for a film project is now treated as one—is production designer, filmmaker, and artist Aradhana Seth’s “The Merchant of Images” project. The studio was created primarily as a prop to make a wedding portrait of actors Om Puri and Ila Arun for the 2010 film West is West. The studio set up was such a hit with the film’s crew that they insisted on having their portraits taken in the studio too. This sparked the idea of turning the studio into a mobile artwork.

Today a public art initiative, the studio—first launched in 2015 at the Indian Summer Festival in Vancouver—has since traveled to festivals and art shows across the globe, including the Indian Art Fair in Delhi, the Format17 festival in Derby, and most recently Dublin in mid-March this year, revolutionizing the idea of the artist diary as an archive of infinite possibilities.

“In a sense, what you see onscreen is the final product,” Seth explained. “But all the architectural drawings, all the props, each action prop, the set dressing, the ideating and all the making… many forms of artwork go into it.” Designing a film set, she added, is all about “getting into the head of the person you’re designing on the script.” For Seth, this includes conceiving every little detail, from the character’s bookshelves to their bed to their grandfather’s portrait, which forms their world on screen.

Seth’s work expands the notion of the diary as a home for the artist’s research and records, where the process becomes the final artwork. Her 2017 show “Set Reset,” in collaboration with the Srishti School of Design, Bengaluru, displayed her years of research in creating, in great detail, the world of movies, which she infuses with life.

Similarly, her 2023 book Sadak, an ode to hand-painted sign boards on shops popular in 1990s India, derives from her extensive photographic archive built on decades of observation and documentation, complete with biographies of the painters who made these signs. By creating a book from her archive, Seth shifts the focus from the large scene to the tiny, often omissible details in a movie frame, that are generally lost to the backdrop. She subtly reminds the viewer that every bit of what makes the whole is a conscious effort, pulled together from piles of extensive notes.

As though bringing to life Seth’s words, Shroff shares an experience that truly felt like an intimate look into the artist’s mind. A Frederico Fellini retrospective she attended exhibited the Italian filmmaker’s sketchbooks. These books revealed that most of the set design drawings for his films were made by Fellini himself. These documents of process interest Shroff more than the finished work, addressing questions like, “Where is your research? Where is your source material? What are your trajectories of thinking?”

A Wellspring Of Citations

Last year, a workshop with the Mumbai launch of Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt at Tarq Art Gallery brought together artists, writers, designers, curators, and lawyers. Each was tasked with producing art from two play project exercises. While a sculptor cut up the book, molding it into something new, an actor recorded the conversations in the room, creating his version of audio art.

Similarly, the Education and Outreach arm of the Vadodara-based Ark Foundation for the Arts held a workshop in October 2024 titled “Artists at Play” for members of an NGO. Reinterpreting lines from a Priyakant Maniyar poem quoted in Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt, the participants were asked to paint something they had never seen before. The focus was on improvization, imagination, and freeing art from the stereotypes and constraints of being market–oriented.

“We are trying to present to them artists who have different premises,” explained Subha De, who heads the program at Ark. “And it’s not only about selling the works. It is also about research, it’s also a process. It’s also about love and conviction. And it is also about humanity, in a bigger way.”

Bhatt’s notebooks, an amalgam of myriad inspirations ranging from mythology and the folk arts to literature and poetry, reflect De’s words well. The workshop also featured a study of works by artists Nandalal Bose and Paul Klee, both also teachers. Here, one can’t help but think of artist Madhavi Parekh, who taught herself to paint using Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925) as a guide, invoking in her work a similar proclivity towards a primeval, native wonder that Klee’s works exude.

Shroff and Solanki view Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt as a wellspring of citations, with one source inevitably leading to another. But Solanki also hopes that the book becomes a first citation for some readers, as anything worth its salt must.

Play Projects x Jyoti Bhatt is available to purchase on Tarq’s website. You can find it here.