‘If we stop, the Taliban wins’: Afghan women resist education ban

In August 2021, the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan marked the beginning of a dark chapter for the country’s women and girls. Overnight, many classrooms fell silent, universities emptied and dreams of education were destroyed. For millions of Afghan girls and young women, the right to learn became a forbidden aspiration. Yet, in the face of oppression, a quiet resistance has emerged. Afghan women have been finding ways, such as underground schools and online classrooms, to reclaim their access to education.

After seizing power, the Taliban prohibited girl students from attending secondary schools, and by 2022, they extended the ban to universities. Currently, Afghanistan is the sole country in the world that prohibits secondary and higher education for girls and women; they can continue education only till sixth grade. According to the latest UNESCO data, as many as 1.4 million Afghan girls have been forced to stay out of school.

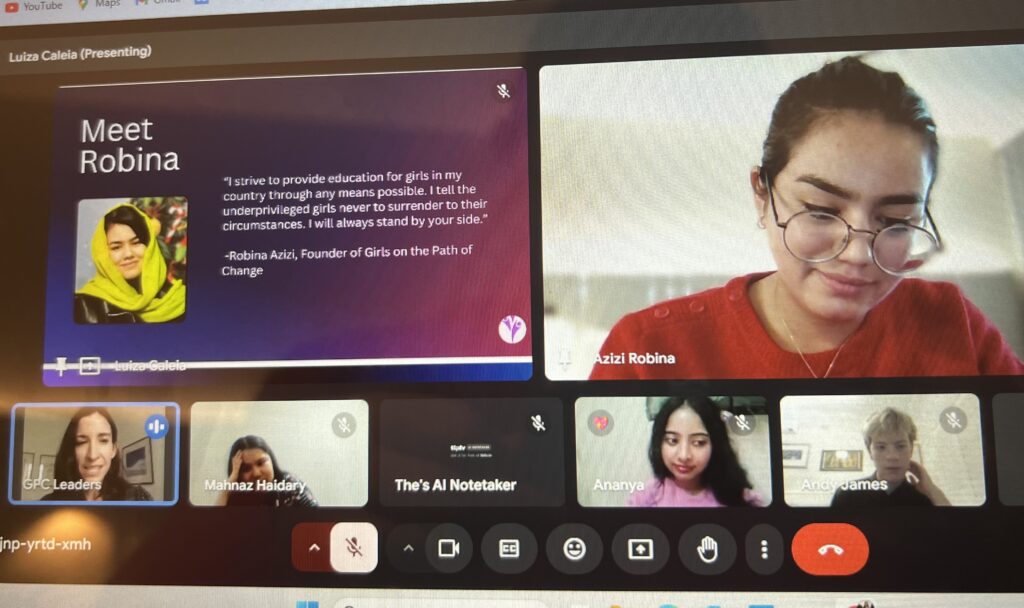

Against this backdrop, Robina Azizi, founder of Girls on the Path of Change (GPC), has become a symbol of the education movement for Afghan girls, and she is far from alone. Across Afghanistan and its global diaspora, several individuals and organisations are working towards facilitating access to education for half of the country’s population.

Robina Azizi: A voice for the voiceless

Azizi was 16 years old when she was forced to flee her home in Balkh province in 2021, when the Taliban took over the area. She unwillingly left behind her books, her school and the life she had known. “I sat in the corner of the room, filled with sadness and regret, shedding tears,” she recalled. “I kept saying, ‘What will become of my school? I cannot leave; I have an exam tomorrow.’ But I had to go.” After she arrived in Kabul with her family, she continued her education in secret. Eventually, following the Taliban’s tightening grip on women’s rights, Azizi had to leave Afghanistan in 2021.

Today, Azizi heads the GPC, an online platform that provides education to thousands of Afghan girls. “I promised myself that one day, I would prove that no door can prevent a girl from reaching her dreams,” she told us.

“We are not just fighting for ourselves,” Azizi said. “We are fighting for the future of our country. Because an educated girl is a powerful girl. And a powerful girl can change the world.”

Her organisation offers English classes, leadership training and even TOEFL preparation, helping girls like Farzana, a 19-year-old aspiring computer scientist, continue their studies despite Taliban-imposed restrictions.

Azizi points out that her work is just one piece in a larger puzzle. “This is not about me,” she said. “It is about all the girls who refuse to give up. It is about the teachers who risk their lives to teach, the families who support their daughters, and the global community that stands with us.”

Alternative learning

Technology has become a crucial tool in the fight for education. Platforms such as Zoom and Google Classroom have enabled organisations like GPC to reach students across Afghanistan, while social media has amplified their voices on the global stage. Yet, for many, access remains a challenge as not all Afghan girls have internet connectivity or digital devices. “The internet is a major issue,” said Farzana, a GPC student. “Sometimes the connection is so slow that I can’t join my classes. And not everyone has a smartphone or a laptop.”

Despite these challenges, technology has opened doors that seemed closed as the Taliban took over the country and started cracking down on women’s rights. “Online learning is not perfect,” Azizi admitted. “But it’s better than nothing. It’s giving girls a chance to dream again.”

In rural areas, where connectivity is scarce and the Taliban’s presence is strong, underground schools have become a vital alternative. One such school operates in a small village in Parwan province. Run by a former teacher who requested to be identified as Zahra, the school has 30 girls aged between 10 to 16. Classes are held in a hidden basement, with students arriving in small groups to avoid suspicion. “We don’t have textbooks or proper supplies,” Zahra explained. “But we have determination. These girls know that education is their only way out.”

However, this work brings great risks with it. In October 2023, another underground school in Kabul was raided by the Taliban forces. The teacher was arrested, and students were warned never to return. Yet, these covert schools continue to operate. “We have no choice,” Zahra said, “If we stop, the Taliban wins.”

Global efforts for Afghan girls’ education

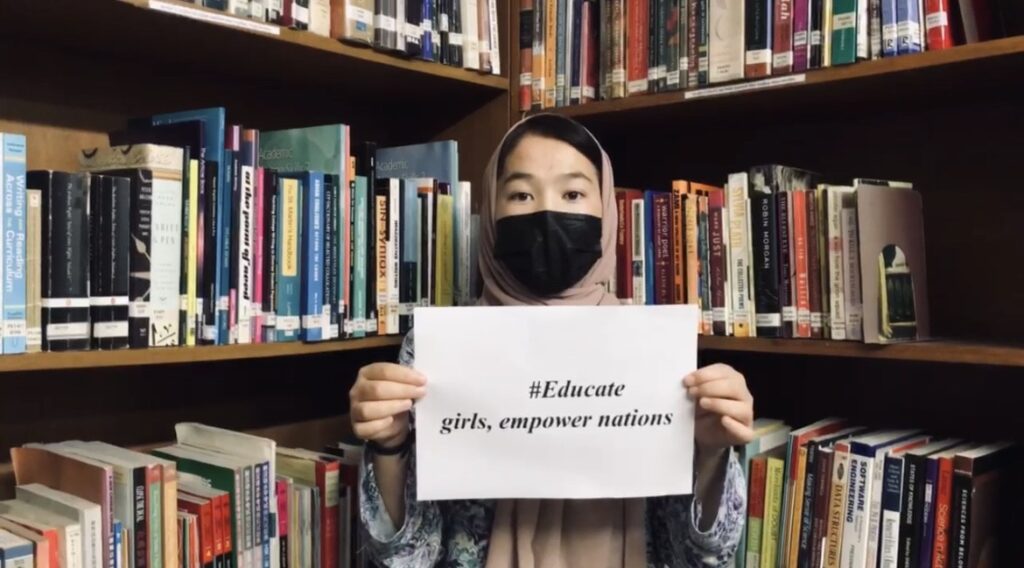

For women and girls who have fled Afghanistan, the fight for education has found a new dimension. From Pakistan to Germany to the United States, members of the Afghan diaspora are using their platforms to advocate for those who continue to live in their suppressed homeland.

In Pakistan’s capital Islamabad, 22-year-old Mariam Noori runs a small learning centre for Afghan refugee girls. “Many of these girls have never been to school,” she said. “They don’t know how to read or write. But they are eager to learn.” Noori’s centre offers basic literacy classes, as well as vocational training in sewing and embroidery. “Education is not just about books,” she added. “It’s about giving these girls the skills they need to survive.”

Meanwhile, in Germany, a group of Afghan women launched an online campaign called “#LetAfghanGirlsLearn” in April 2023. The campaign, which has garnered international attention, calls on global leaders to pressure the Taliban to reopen schools and universities. “We cannot let the world forget about Afghan girls,” said the campaign organiser Laila Ahmed, adding, “Their future depends on us.” What began as a solo effort has now grown into a bigger team of ten volunteers, with more than 600 students graduating from GPC classes in 2023. The community is now expanding to include more teachers and students.

4th year of Afghan girls barred from school! a crime against humanity. Education, our most precious right, is stolen from them. The world’s silence is deafening. Taliban fear their minds, but we must fight for their future. #LetAfghanGirlsLearn #EveryHomeASchool#NoToTaliban pic.twitter.com/IhOf4MLgjX

— Horizon (@Horizon0707070) March 20, 2025

The fight for Afghan girls’ education is not just an Afghan issue—it is a global one. Organisations like UNICEF and UNESCO have condemned the Taliban’s education ban, while governments around the world have pledged support for Afghan women and girls. Yet, many activists argue that more needs to be done.

“The international community must not look away,” says Luiza Caleia, a 17-year-old Brazilian volunteer with the GPC. “Afghan girls have dreams, and it’s our responsibility to help them achieve those dreams.” Caleia, who leads the GPC’s international ambassadors’ team, has been instrumental in raising awareness about the issue. “Every small action counts,” she said. “Whether it’s sharing a post on social media or donating to an organisation, we can all make a difference.”

Many women who fled Afghanistan and are living in neighbouring Pakistan, including those advocating for the education of girls, are now facing forced returns. Pakistan has bumped up efforts to deport Afghan refugees; its policy of “relocating” undocumented Afghans has expanded to include even those holding UNHCR-issued Afghan Citizen Cards. With relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan deteriorating, Islamabad is showing little humanitarian concern as it endangers female activists and human rights defenders, who would face near-certain persecution under Taliban rule.

Dreams deferred, but hopes preserved

For Afghan girls, the education ban is not just a denial of their rights—it is a crushing blow to their sense of self-worth and future. The psychological impact of being barred from schools and universities has been profound, leaving many girls to grapple with depression, anxiety, and a sense of despair.

“I used to dream of becoming a doctor,” said 17-year-old Amina, a former student in Herat. “Now, I spend my days at home, helping with chores. I feel like my life has no purpose.” Amina’s story is not unique; across Afghanistan, girls who once filled classrooms with laughter and ambition now describe feeling invisible, as if their dreams have been erased overnight.

Amid this situation, organisations like the GPC and others are not only providing education but also offering emotional support. “We hold regular sessions with psychologists and counselors,” Azizi explained to us. “Many of these girls have lost their sense of identity. We remind them that they are not alone, that their dreams still matter.”

The act of learning itself has become a form of therapy for some. “When I join my online classes, I forget about the Taliban,” said a 15-year-old girl from Kabul. “For those few hours, I feel like myself again. I feel like I have a future.”

Afghan men as allies

While the focus of the education resistance movement has rightly been on women and girls, men and boys are also playing a crucial role in it. In a society where patriarchal norms often dominate, their support is both unexpected and invaluable.

In Kandahar, 25-year-old Ahmad runs a secret study group for his younger sisters and their friends. “I know how important education is,” he told us. “I see how much my sisters want to learn, and I can’t stand by and do nothing.” Ahmad’s study group meets in a hidden room in his family’s home where a retired teacher conducts classes.

Similarly, in Mazar-i-Sharif, a group of young men has formed a collective to advocate for girls’ education. “We believe that an educated society benefits everyone,” said Farid, one of the group’s leaders. “We organise protests, write letters to the local authorities, and even help girls access online classes. This is not just a women’s issue—it’s a human issue.”

These efforts, though small, are significant. It is not easy for men, even those with power, to lend support to women and girls in the country. Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Taliban’s deputy foreign minister, was reportedly under threat after criticising the education ban, forcing him to flee to the United Arab Emirates. The support for women’s education from men challenges the Taliban’s narrative that the Afghan society supports the education ban and demonstrates that the fight for girls’ education is a collective struggle.

A lost generation

Since their return to power in 2021, the Taliban has systematically dismantled women’s rights, barring them from universities, government jobs, and even public spaces like parks and gyms. Beauty salons, once a source of income for thousands of women, have been shut down. The laws also forbid women from traveling or being in public without a male chaperone. Many are calling the situation a “gender apartheid”. By denying girls access to education, the Taliban is depriving Afghanistan of a generation of doctors, engineers, teachers, and leaders. The long-term consequences of this decision could be devastating.

“Afghanistan cannot afford to lose its women,” said a prominent Afghan human rights activist who wished to remain anonymous. “Women are the backbone of our society. They are the ones who nurture families, build communities, and drive progress. By denying them education, the Taliban is not just harming women—they are harming the entire country.”

The restrictions have also plunged countless families into economic despair. The impact is already being felt as many families who once relied upon their daughters’ education for a better future are now struggling to make ends meet. “My daughter was studying to become a teacher,” said a mother from Ghazni. “Now, she sits at home, and we have no income. The Taliban has taken away our hope and our future.”

In 2023, the United States Institute of Peace reported that the educational gains Afghanistan made from 2001 to 2021 stand in stark contrast to the current situation under the Taliban’s rule. During those two decades, the country’s education sector thrived, with girls accessing education across all 34 provinces at all levels—except in Taliban-controlled areas. From 2002 to 2021, nearly 3.8 million girls enrolled in grades one through twelve. By 2020-2021, Afghanistan had 18,765 public and private schools and over 200,000 teachers, including 80,554 women. Higher education also flourished, with more than 100,000 women enrolled in universities and 2,439 female lecturers contributing to academia.

These educational advancements translated into broader societal progress. Women held 63 seats in parliament, nine ministerial positions, and 280 judgeships, with over 500 female prosecutors. Additionally, more than 2,000 women-owned small and medium-sized businesses operated across the country. Women and girls not only accessed education but also actively shaped Afghanistan’s future through leadership, entrepreneurship, and justice.

The Taliban’s return in 2021 erased these hard-won achievements, plunging the country into a regressive era. Women were barred from public life, and opportunities for growth were dismantled. The contrast between the progress of the past two decades and the current reality underscores the devastating impact of the Taliban’s policies on Afghanistan’s future.

However, Afghan girls and women relentlessly continue to carve pathways to learning, refusing to let their futures be dictated by repression. Their determination, whether through secret classrooms, digital platforms, or global advocacy, is a testament to the unyielding hunger for knowledge and justice.