The Unfinished Revolution of Black Artists in Post-BLM London

The year 2020 will go down in history for many reasons, the most obvious being the global pandemic that fundamentally changed life as we know it, but also the explosion of the Black Lives Matter Movement, fueled by the murder of George Floyd. The tragedy sparked months of global protests against not only the injustice but also the years of police brutality, discrimination, and systemic racism faced by members of the Black community.

Many considered it an international awakening to the struggles faced by African American people for centuries. But its global impact extended its reach far beyond both its place and subject matter of origin.

Protests took place in 60 countries and across every continent except Antarctica. In Nigeria, it inspired thousands of people to take a stand against the longstanding police brutality through the #EndSARS movement, and in Belgium, people set fire to a statue of King Leopold II as the movement reminded people of the violence he had committed against the Congolese during the colonial era.

Like these countries, the UK had to reckon with its history of police brutality and systemic racism. George Floyd’s murder particularly struck a chord as the country was still reeling from the largest civil unrest it had seen for a generation after police shot and killed 29-year-old Mark Duggan in 2011.

That was just one example of the many incidents of racially motivated police violence in the UK. 2023 research from the UK government found that the Metropolitan Police, which refers to the police force in London, was 3.2 times more likely to use force on Black people than white people.

A mirror was held up to the nation, so workplace diversity and inclusion initiatives skyrocketed across sectors. The Multicultural Britain survey, conducted by market research company Opinium and advocacy organisation Reboot, discovered a 40% increase in workplace action to solve diversity issues in 2020.

London’s visual art world was no exception to this widespread change. Institutions such as the Tate Britain and the Victoria and Albert Museum made public commitments to becoming more inclusive organizations and rolled out initiatives to improve diversity. Both institutions established dedicated anti-racism task forces focused on diversifying their collections, workforce, and audiences. The V&A committed to embedding global narratives through exhibitions and programming while creating mechanisms for reporting behaviors that don’t reflect their values. The Tate implemented mandatory anti-racism training, worked to amplify the voices of artists of color, and published regular progress reports on its website.

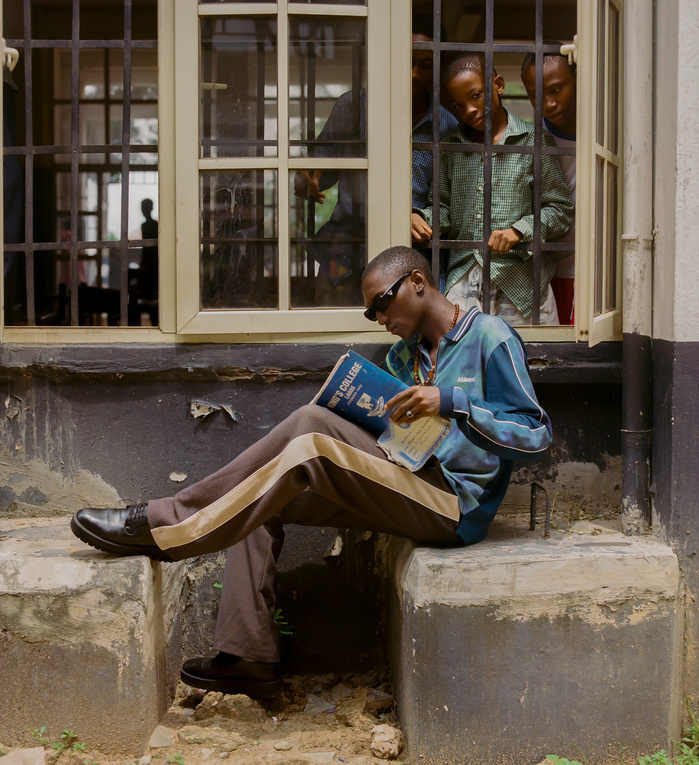

Nearly five years from this “tectonic shift”, as London and Lagos-based photographer Kemka Ajoku described it to me, we can ask: how much tangible progress has been made for Black artists in London? And what progress remains to be seen?

An Institutional Shift in London’s Art Scene

When the world began to reopen after the pandemic in 2021, the most visible change was in exhibitions. War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truth and Rights (7 July–26 September 2021) broke attendance records at the Institute for Contemporary Art in London. The show was originally scheduled to open in May 2020. But it was delayed due to the pandemic, and that turned out to be a blessing as it directly confronted the issues of state violence and institutional racism that people sought to address.

The past few years have also seen countless shows in mainstream art institutions emphasizing Black culture. The V&A’s Africa Fashion (2 July 2022–16 April 2023), the Hayward Gallery’s In the Black Fantastic (19 June–18 September 2022), and Tate Britain’s Hew Locke: The Procession (22 March 2022–22 January 2023) are just a few examples.

These exhibitions collectively reveal a change in curatorial focus towards challenging the historical centering of white, Western perspectives and spotlighting alternative approaches. Africa Fashion celebrated the continent’s fashion as a self-defining art form; In the Black Fantastic employed fantasy and Afrofuturism as tools for creative liberation and confronting social injustice; Hew Locke’s The Procession engaged with colonial legacies and financial power structures.

The shift in shows was coupled with the increased acquisition of work by Black artists from major institutions, according to London-based curator and contemporary artist Abigail Fakoya. Nigerian-born and raised in Grenada, 28-year-old Fakoya works as a gallery assistant at Gallery 1957 in Kensington, London. “It was an uncovering of contemporary and historical Black artists,” she told me. “Those institutions said, ‘Let’s do some research and bring them forward.’”

Many organizations also looked inward at the lack of diversity in their staff. London art galleries made commitments and rolled out action plans to create a more representative workforce. Tate Britain, for example, set out to recruit 50 paid apprentices to attract diverse talent, while The Barbican reviewed its recruitment process to reduce bias.

Fakoya, who recently curated an exhibition featuring the work of seventeen contemporary artists and creatives who share the intersectional identity of ‘Black Woman’ titled Radiant (28 November–1 December 2024), also highlighted an upswing in the value of work by Black artists, due to increased interest from established collectors trying to diversify their collections, as well as new collection primarily focused on purchasing Black art.

In November 2021, Black British painter Hurvin Anderson sold his painting Audition at Christie’s 20th/21st Century Evening Sale for over five times what it was estimated at, over $10 million, becoming one of the most expensive artworks by a living Black artist and tripling his previous benchmark. Paintings by Black artists were the top two sales of that evening, with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Because It Hurts The Lungs selling for more than $11 million and dominating the auction.

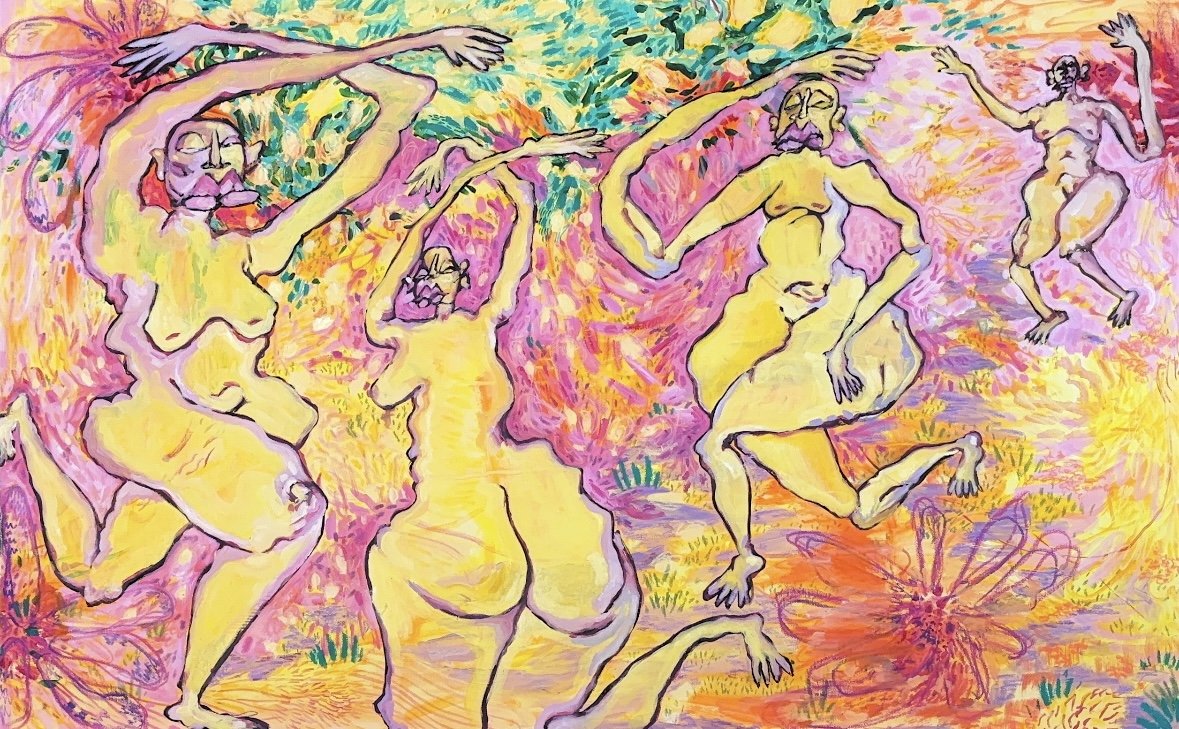

London-based artists personally felt and witnessed this transformation, whether in the benefits for their careers or those around them. British Congolese visual artist Joy Yamusangie shared that they experienced increased commissioned work and art sales. “It generally seemed like there was more interest from galleries, potential buyers, and people on social media in supporting my work,” they told me. They specialize in illustration and use drawing, film, painting, and collaging to create mixed-media pieces.

Multidisciplinary artist and community coordinator Kandre Hassan felt she finally had a voice. “After 2020, I was more comfortable identifying as an artist and mobilizing change,” she shared. “That time was definitely a catalyst for a lot of artists to finally step out of their shells and start expressing themselves.” 23-year-old Hassan delivers introspective art workshops and is drawn to the metaphysical, often drawing from West African spirituality in her paintings as an ode to her Nigerian heritage.

However, there was widespread concern about how sustainable these changes would be and whether the benefits would fade over time.

“It was being questioned whether it was a fad,” explained London-based visual artist, curator, and writer Bunmi Agusto. “It was always worrying when people were referring to this rising attention as a trend, as opposed to a correction.”

The Double-Edged Sword of Representation

Unfortunately, Agusto’s assessment was accurate in many ways.

Yamusangie shared that the increased interest they witnessed only lasted a year and a half, and the dream commission they received in 2020 to illustrate the cover for the 2021 Penguin edition of C. L. R. James’s Minty Alley was the first and only of its kind.

Ajoku, who has photographed public figures such as Bukayo Saka, Ambika Mod, and Ncuti Gatwa, echoed Yamusangie’s sentiment, highlighting that many Black artist-focused initiatives have tapered out in the past two years.

However, some artists made the most of it. “You could tell that a lot of initiatives were made and put into industries where they had to give back, and it was a box they had to tick,” reasoned 26-year-old Ajoku. “At first, I thought they were playing the game, we should too, and shouldn’t pass up on the opportunities. But at some point, it became really obvious.”

For Hassan, who also creates poetry and illustrations, this shift might facilitate a natural evolution. Now that the increased visibility is normalized, she said, there might be space for Black artists to explore their expression outside of institutional constraints that pigeonhole Black artists to certain forms of expression.

“Because you’re Black, you had to talk about Black identity and align your practice with certain topics, or forfeit commercial success,” Fakoya elaborated. “It might not be an overt thing that galleries were saying, but I think the process of getting representation or access to opportunities definitely implied that you needed to lean one way.”

Hassan, who has collaborated on social change projects with Greenpeace, Evolutionary Arts Hackney, and The Africa Centre during her career, added that this pressure typically took shape via an overemphasis on figurative Black portraiture, emphasizing suffering in some way, which sidelined other art styles.

Many of the London exhibitions highlighting Black artists often center work that depicts Black bodies in the figurative style. Looking at Tate’s “Black identities and art” section, for example, which is dedicated to discovering Black art and artists in its collection, five out of the seven Black artists spotlighted focus on Black figuration, from Zanele Muholi’s self-portraits to Lubaina Himid’s figurative paintings.

Hassan’s perception of inferred suffering is likely linked to the politicization of Black figurative art in exhibition materials, with galleries often emphasizing the cultural aspects of the artist’s identity and experiences even when the work makes no direct reference to it.

For example, gallery descriptions of London-based figurative artist Kudzanai-Violet Hwami consistently emphasise her upbringing in Zimbabwe and South Africa before moving to the UK as a core inspiration for her work, but she has previously stated in 2019 interview with Studio International that while her upbringing is a major influence, her work isn’t created solely through that lens. She tells Jessica Draper, “Making work about being a lesbian or a Zimbabwean woman, for example, isn’t enough for me to make paintings. These facts are unavoidable hardware subjects.”

Writer John-Baptiste Oduor has previously identified this approach of highlighting cultural backgrounds as an “anti-critical disposition” in discussions of Black artists’ work.

“I would love to see new, emergent forms of art, which I think is slowly being introduced,” expressed Hassan, a previous leader of art workshops for Tate Britain, London Fashion Week, and The Whitworth Gallery. “It’s just not every day that we should have to see realistic, figurative art focused on Black suffering.”

British Nigerian abstract painter Jade Fadojutimi’s success illustrates this gradual change. In October 2021, two of her paintings were bought at auction for more than £1m each, with one called Myths of Pleasure going for 15 times its estimate. In an interview with The Guardian, she said, “There’s been a lot of people who look at my work and say it doesn’t look like I’m Black. And I think, ‘Well, question that statement.’ My practice rejects labels and celebrates individuality without contextualizing someone into a category.”

This boxing-in includes how artists were described within the media and encouraged to describe their work in artist statements, according to University of Oxford MFA graduate Agusto. She recalled the press describing her as a “Nigerian-born British” artist, despite growing up in Lagos and only moving to the UK at 16. “When my work is written about, it’s often conflated to Britishness or reduced to certain buzzwords,” she noted. This is challenging for artists like Agusto because it sacrifices the individuality of her experience to favor a more marketable identity.

Agusto, whose work has been exhibited in Saatchi Gallery, Dada Gallery, and Copeland Gallery, also argued that the limited space afforded to Black artists led some of her peers who had also grown up in Nigeria—and didn’t have the same experience of race identity that was commercially successful—to project experiences that weren’t entirely authentic to gain the international acclaim that many Africans are made to feel is the pinnacle of success.

“There is an important distinction between Blackness and Africanness, and people need to be true to their experiences because there is danger in a single story,” she explained. “Some African artists co-opted African-American issues because many collectors trying to diversify their collections leaned towards the more political Black portraiture.”

Black portraiture rose to popularity with the Black Lives Matter movement due to the historical erasure of Black identity from British portraiture, making the mere existence of Black figures in paintings inherently political, and its emergence in the past ten years wildly popular. The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure (22 February–19 May 2024) was one example of an exhibition speaking to this, as it examined the absence of historical portraiture in Western art history by reclaiming it.

A Case for Artist-Led Transformation

Looking ahead at the substantive changes needed to create truly equitable space for Black artists in London, many of my interviewees encouraged looking away from the responsibility of existing institutions and reframing the entire landscape with an artist-focused approach.

According to 25-year-old Agusto, Black creatives must create more “for us, by us” spaces. For instance, she cited examples in Lagos, such as The Treehouse, an experimental art space, and Padà, a guesthouse that frequently hosts exhibitions and community-building activities. “I’m more interested in Black people creating our own systems of power,” she said. Both spaces seek to encourage creative expression and experimentation by allowing artists to host their own exhibitions without backing from art institutions, shifting the power from the gatekeepers to the creators.

Hassan concurred, using the “white cube” gallery space as an example, where art is engaged outside the Western context far more accessibly and immersively, encouraging Black artists to lean into more alternative aspects of their creative expression. One example of Kandre’s suggestion can be seen in the debut solo show of Nigerian British artist Teoni, which was held in a warehouse-style studio apartment complete with a kitchen and living room. The figurative artist also employed a “no guest list” policy for her private view, creating accessibility for fans who weren’t art professionals.

Ajoku suggested that having interdisciplinary Black creative communities could also be helpful for Black artists looking to break free of the creative box they’ve been placed in. “Iron sharpens iron, but not in the typical sense,” he said. “If I’m in a room with another photographer, they may not inspire me as much as if I’m in the room with a musician or a writer. Being able to express what we go through as creatives helps people.”

The Black Lives Matter movement served as an instrumental reckoning for the world. It accelerated progress for Black artists in London while inspiring a new generation. However, it also made many Black artists believe their work could only be successful if it looked like the commercially successful portraiture that emphasized their racial experience or cultural identities.

Nearly five years later, many Black artists welcome the tapering out of diversity initiatives and look to the community to uplift and improve itself. The space has been made for them; now, they want to determine how it’s filled.