Nostalgia and Reflection: Revisiting Veer Zaara Amid Bollywood Re-Releases

It is 2004. A new central government has just been formed in India, the Indian National Congress seems to have regained its strength after eight years out of power. Manmohan Singh has been named the Prime Minister of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, the first Sikh and non-Hindu to be so.

In November, Veer Zaara, a cross-border romance involving an Indian man and a Pakistani woman, hits theatres. In the mix of single screens and the fast-growing world of multiplexes, the Yash Chopra-directed film makes a box-office collection of over Rs. 98 crores worldwide, nearly five times its budget. In today’s terms, this collection would translate to over 300 crore rupees.

Veer Zaara opens with the voice of Chopra himself, reciting a poem, and to the visuals of a rising sun behind a mountain range, deep yellow mustard fields, a misty stretch of forest, and a sprawling sunflower field. Soon, Shah Rukh Khan, the lead actor, appears on screen to lip-sync the verses of Kyun Hawa Aaj Yun Gaa Rahi Hai (Why Is The Wind Singing Today).

He stretches his arms in his trademark fashion, walks, and runs across rich fields that the audience can easily recognize as Switzerland but will pretend is their dear India. Around the actor’s neck, a chain with a pendant—unmistakably, the Khanda icon, an important symbol for the Sikhs. In an instant, the magic of the open, endless outdoors breaks as the lead actor wakes up from his dream in his prison cell in Lahore, Pakistan.

Today, movie dialogues have moved from poetic verses in bookish Hindi to realistic dialects from where the stories are based. They have also mostly moved out of the studio that we encounter throughout films like Veer Zaara, and into real locations. We are now used to a new kind of storytelling. Yet, the poetic dialogues and orchestra-like music of old films evoke a deep sense of longing.

Nostalgia In The Time Of Hindu Nationalism

In 2024, when Veer Zaara was re-released on its twentieth anniversary, a common refrain among audiences was that such a film could never be made today—referring to the now pervasive religious nationalism in the country and increasingly, on screen. Following the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party’s ascend to power in 2014, Hindi cinema audiences have seen a string of mainstream releases—from Uri to Fighter to Singham Again—that depict acts of “terrorism,” against the state or its citizens, often “inspired” by real events concerning border conflicts.

The villain, we are taught in these narratives, is the ruthless Muslim, overcome with passion whether for power and land or simply a jihad that seems to require no other further explanation.

In the face of this propaganda, is the phenomenon of an increased number of old films being re-released on the big screen—Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Rockstar (2011), Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein (2001), Tumbbad (2018). Even while all these films are readily available for streaming, the experience of arriving at the cinema hall, watching the familiar images on the big screen, and singing along to the songs we now know by heart are all packaged—with the help of social media—as nostalgic, a worthy expenditure.

The idea of nostalgia, we are told, underpins this desire to watch older stories in the cinema. As the stories return to us, we are forced to make sense of this nostalgia—in this case, for a supposedly secular and harmonious past. In her 2001 book, The Future of Nostalgia, artist and cultural theorist Svetlana Boym examines how Russian classical literature in the nineteenth century became the nation’s repository of nostalgic myths, and how popular culture in the US became the medium to spread the American way of life.

But first, she breaks down the terms—nostos (return home) and algia (longing)—as a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Boym points out that nostalgia is not experienced as a longing for a place but a yearning for a different time better or slower, that can be revisited like space. She also reminds us that historians often considered nostalgia to carry a negative connotation—a history without guilt, an abdication of personal responsibility.

When we celebrate the fact that two decades ago the climax of Veer Zaara was able to overturn what its protagonist laments early in the film: Veer aur Zaara ke naam kabhi saath mein nahi liya jaa sakta (Veer—a Hindu man’s name—and Zaara—a Muslim woman’s name—can never be said together), we may be missing the finer details that make up the film. Unpacking these details lets us assess whether a celebration of and a longing for the old times are well-founded.

This is perhaps why, while some Indian intellectuals mourn the end of an era that represented religious tolerance and harmony—the defeat of Hinduism against Hindutva, others point out the fallacy of this difference.

Nostalgia is Thriving With Veer Zaara

In terms of numbers, while new films are quick to reach the “300 crore club,” re-releases only average around Rs 7 crore (except for Tumbbad’s Rs 32 crore). Veer-Zaara is reported to have finally crossed the 100 crore mark through its various re-releases, the September 2024 one being the latest.

The numbers do not suggest that the re-releases are a highly profitable business model, but they certainly hint at a cultural success. In that, they not only keep the audience coming back to the cinema hall but also bring into popular circulation the stories, themes, and characters of the past. Revisiting Veer Zaara helps us see why.

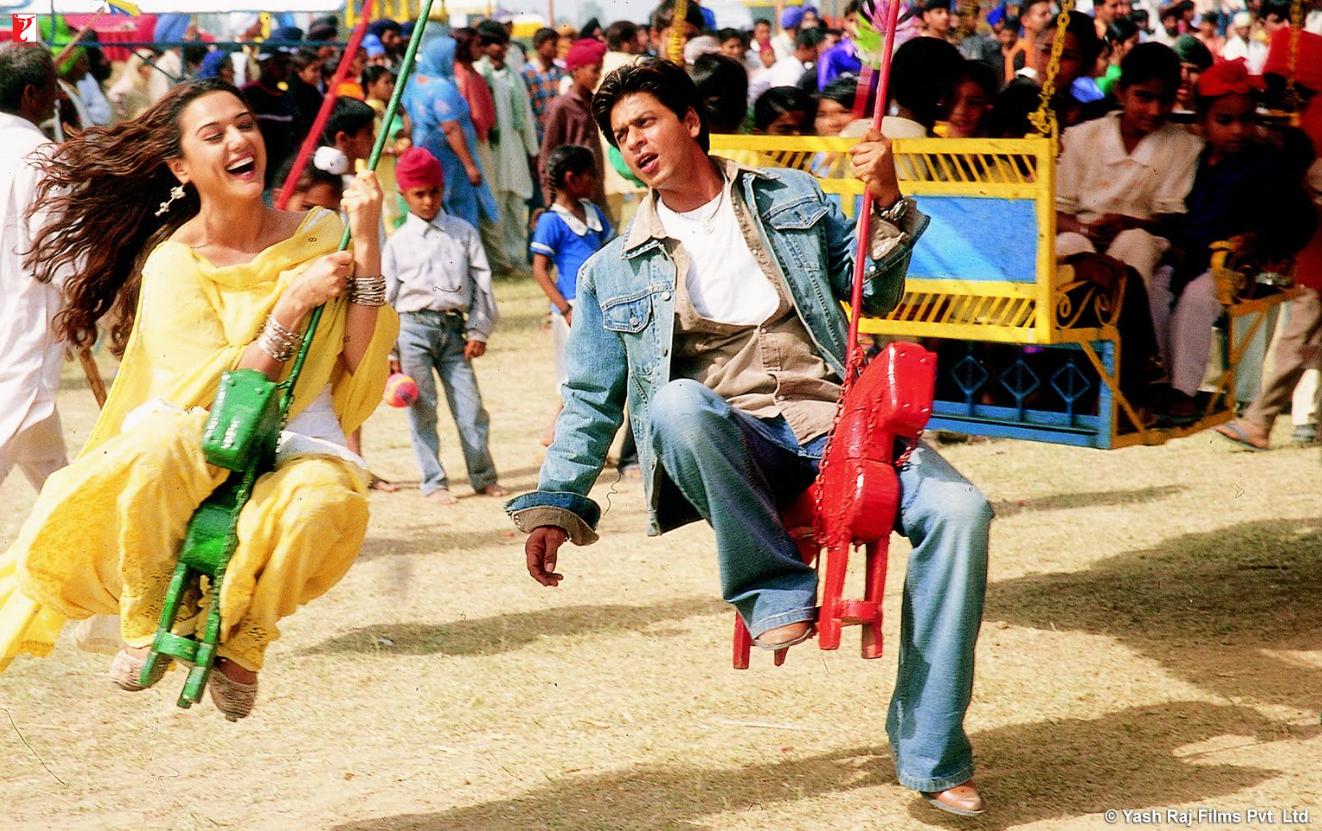

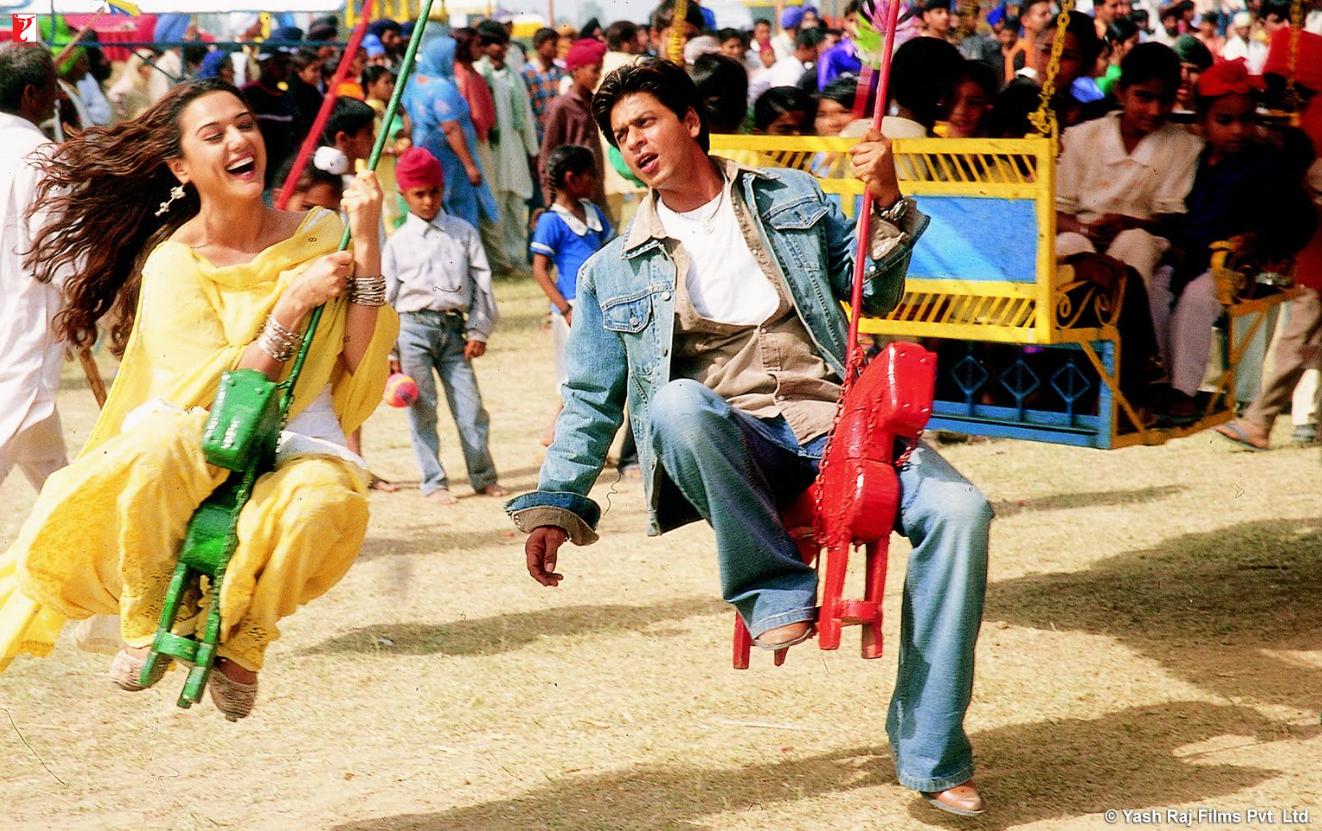

As squadron leader Veer Pratap Singh (SRK) on a mission to rescue the passengers of a bus accident, saves Zaara Hayaat Khan (Preity Zinta), the young woman from Pakistan, the piano chimes in with the famous tune of Tere Liye (For You). The audience already knows the song and sings along. Whistles and hoots fill the air.

Here on, we are told repeatedly that this young man is Hindustani, with little to no reference to his religion, other than as a cultural or regional identity—in that, he seems to celebrate Lohri.

We are introduced to his land, the land of Punjab—lush green, with brimming ponds, women carrying water in their matkas, or simply running along mustard fields, and swaying on swings suspended from trees, their colorful dupattas fluttering in the wind. We even see a Radha Krishna reference with a young man playing a flute under a tree while a young woman listens in awe.

This is India, we are told, united and thriving: Dharti Sunehri, Ambar Neela (where the earth is golden and the skies are blue). This is rural India, with no sight of poverty or hunger, but where familial values keep everyone content.

After this quick summary of an entire nation that we receive through the eyes of Zaara, it is time for her to head back home. Just as Zaara is to board the train to Lahore with her fiancée, Raza, Veer confesses his love for her, leaving her confused and yearning for him. When the audience returns from the interval, Veer, who hears of Zaara’s suffering, resigns from the Indian Air Force to travel to Pakistan and fetch her.

On reaching Lahore, however, he is confronted with Zaara’s family and their desperation to protect the family honor, and her fiancée Raza’s polite rage that falsely charges him of being a spy for the Indian state. We watch as Veer, in the attempt to protect Zaara’s honor, dramatically accepts this false identity, and thus, his fate of being held in Pakistan as a political prisoner.

Veer chooses the path of quiet sacrifice that is often only attributed to women. He chooses unconditional love in the face of a vengeful Pakistani man. In this act of subversion, he tugs at the hearts of audiences. As we listen to the melancholic Do pal ruka khwabon ka karwan (This caravan of dreams stopped for just a couple of moments) when the two protagonists separate ways, we crave them to come together again.

The Language of Love, Friendship, and Peace

When Veer Zaara released in 2004, the ecosystem seemed to have allowed films to speak this language—of love, friendship, and peace between India and Pakistan. It was then possible for a man in uniform to appear in a film without wielding a single weapon and still become a hero. The ecosystem seems to have remained somewhat similar till 2010 when the Times of India and The Jang Group of Pakistan established a joint campaign named Aman ki Aasha (Hope for Peace) for diplomatic and cultural relations between the two nations.

Earlier in 2004, SRK starred in Main Hoon Na which had, in its background, Project Milaap, a fictional program of truce and reparation between the two nation-states. This time, however, the story was replete with guns, combat, and grenades, all to save the nation from its own terrorist—a Hindu man with misplaced anger. Today, these characters only come back through re-releases, as the newer big-screen releases are interested only in Pakistan-bashing.

Other elements too are unlikely to find space on the big screen today. The figure of the mother is brought up to convey that the two nations, and thus, two religions have more in common. When Veer is reminded of his mother’s cooking while eating the food his lawyer Saamia’s mother prepares, she tells him that the food prepared by mothers everywhere tastes the same. In another instance, Veer assures Zaara’s mother that he empathizes with her because “all mothers in his own country are exactly like her.”

However, critically examining the good old past is more useful than simply celebrating it. Throughout his endeavor, Veer’s identity as Sikh remains a cultural symbol, superseded by his identity as Hindustani but Zaara’s Muslim identity becomes a religious and indeed political one as her family’s electoral success hinges on her marriage. The Khanda around Veer’s neck, however, is a symbol to be reckoned with.

Today, as political tensions rise around the question of Khalistan, and global forces get deeply intertwined, how are we to read the reiteration of Veer’s identity as primarily Hindustani?

Is The Nostalgia Warranted?

In his 1998 book, Ideology of the Hindi Film, scholar Madhava Prasad stresses the significance of Film Studies and how it has been useful in defining culture as an object of study. He builds on the French philosopher Louis Althusser’s theory of ideological state apparatuses, distinguishing between direct domination and ideology.

In Marxist terms, ideology can be understood as the universalization of the particular interests of a class. It can also be understood as individuals being constituted as subjects of a social structure. This theory helps us see the state and apparatuses such as family, schools, products, and spaces of culture embodying a prevailing consensus. These apparatuses put ideologies into circulation among people.

Prasad, thus, places cultural production within the political and economic framework of the Indian nation-state. He proposes a critical reading of Indian cinema, especially popular or mainstream cinema, as a site of ideological production and reproduction of the state form. By analyzing films across decades in this framework, he demonstrates how Indian cinema, throughout its history, is related to the specificity of the socio-political formation of the Indian nation-state. Here, we witness the contestations within India over the form and character of the state.

But in the epic Indian love story that Veer Zaara is made out to be, the specific experiences of the Sikh population are ignored, and Veer’s character is incessantly called upon to represent Hindustan. In his 2021 book, Sikh Nationalism, Guharpal Singh argues that the narrative of a minority is shaped by the world around it—in this case, the world or context around the Sikh community is the rise of majority nationalism and nation-state formation.

From the time before 1947, the community became the principal “other” in the efforts of both the Congress and the Muslim League. This created a reactive minority response to autonomy and self-determination.

Singh brings attention to the official narratives by subsequent governments of India which persistently portray the regional autonomy movement in Punjab and the diaspora as “Pakistan-led,” completely neglecting the legitimacy of the demand. The co-optation of Veer as primarily and indeed only Hindustani speaks volumes of how Congress has politically managed the religious minority.

Further, as Veer performs his role as the Hindustani fighting to regain his true identity, Veer Zaara calls upon Veer’s young and yet uncorrupted lawyer, Saamia Siddiqui, to take on the male-dominant field of law in Pakistan by proving her mettle in the courtroom in her very first case. The act of highlighting patriarchy operating in the capital city, no less, of a Muslim state is cleverly juxtapositioned with a similar patriarchy only in rural Punjab 22 years in the past where the girls do not yet have a school. Painting this picture of Pakistan only reinforces the stereotype of a patriarchal public sphere in a regressive Muslim state that resists modernization.

Besides, the resolution in Veer Zaara is not just that Zaara, a Muslim woman, is claimed and brought back home by her Hindustani husband, but that the justice system in Pakistan apologizes on behalf of the state for the 22 years that it has taken away from a Hindustani. Suffice it to say the wishful thinking of the state unravels quite clearly in the court judgment.

Why Veer Zaara Still Cannot Be Made Today

Even if these observations, stacked upon one another, make it seem like the wishful thinking of a nationalist Indian government, there is some truth in the refrain that such a film cannot be made today under the current regime. Despite our critical understanding that films may have always spoken the language of the state, the feeling of loss and longing that the audience experiences has to be reconciled.

Perhaps the story of Veer and Zaara, itself premised on their longing for a lost time (with each other) is not one that the current dispensation or its ally Bollywood is interested in telling—focusing rather on exaggerated and unrealistic portrayals of the apparently unending war between the Muslim state and the Indian (Hindu) nation-state.

A cross-border love story that its makers call non-political may well be a thing of the past; an Anupam Kher may never again be forced to speak the language of peace, let alone truth and justice, between the two nations. But is there a way to make sense of the tears we still spill for this and other melodramatic tales of the 2000s?

One answer may lie in Boym’s suggestion of differentiating between restorative and reflective nostalgia. Restorative nostalgia insists it is the absolute truth and tradition, attempting to re-establish and reconstruct the lost home. According to Boym, this is the kind of nostalgia that has been at the core of national and religious revivals. This brings to mind the idea of the Ram Janmabhoomi or even the myth of Akhand Bharat, which claims that various South Asian countries are all part of a “greater India.”

Conversely, the nostalgia of the reflective kind allows thinking about the ambivalences of human longing and belonging. While restorative nostalgia protects the myth of an absolute truth, reflective nostalgia questions and presents an ethical challenge. Reflection here hints at flexibility, not the re-establishment of stasis.

“Restorative nostalgia takes itself dead seriously,” Boym writes. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, can be ironic and humorous. It reveals that longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgment, or critical reflection.”

This reflection is necessary. As Gurharpal Singh points out, Hindu nationalism has easily replaced Congress’ idea of nationalism. This compels us to rethink how the supposed secular state since 1947, and the institutional structures it created to manage religious diversity, perhaps only reinforce domination over religious minorities. This finds reflection in films too.

Perhaps, then, we can find a way to remember and reflect on the past, beyond simplistic celebration of a supposedly long-lost time. This does not mean a straight rejection of all affective responses to the old storytelling that we were once fond of, but remembering and reflecting to make important demands of the future.

Related Posts

Nostalgia and Reflection: Revisiting Veer Zaara Amid Bollywood Re-Releases

It is 2004. A new central government has just been formed in India, the Indian National Congress seems to have regained its strength after eight years out of power. Manmohan Singh has been named the Prime Minister of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, the first Sikh and non-Hindu to be so.

In November, Veer Zaara, a cross-border romance involving an Indian man and a Pakistani woman, hits theatres. In the mix of single screens and the fast-growing world of multiplexes, the Yash Chopra-directed film makes a box-office collection of over Rs. 98 crores worldwide, nearly five times its budget. In today’s terms, this collection would translate to over 300 crore rupees.

Veer Zaara opens with the voice of Chopra himself, reciting a poem, and to the visuals of a rising sun behind a mountain range, deep yellow mustard fields, a misty stretch of forest, and a sprawling sunflower field. Soon, Shah Rukh Khan, the lead actor, appears on screen to lip-sync the verses of Kyun Hawa Aaj Yun Gaa Rahi Hai (Why Is The Wind Singing Today).

He stretches his arms in his trademark fashion, walks, and runs across rich fields that the audience can easily recognize as Switzerland but will pretend is their dear India. Around the actor’s neck, a chain with a pendant—unmistakably, the Khanda icon, an important symbol for the Sikhs. In an instant, the magic of the open, endless outdoors breaks as the lead actor wakes up from his dream in his prison cell in Lahore, Pakistan.

Today, movie dialogues have moved from poetic verses in bookish Hindi to realistic dialects from where the stories are based. They have also mostly moved out of the studio that we encounter throughout films like Veer Zaara, and into real locations. We are now used to a new kind of storytelling. Yet, the poetic dialogues and orchestra-like music of old films evoke a deep sense of longing.

Nostalgia In The Time Of Hindu Nationalism

In 2024, when Veer Zaara was re-released on its twentieth anniversary, a common refrain among audiences was that such a film could never be made today—referring to the now pervasive religious nationalism in the country and increasingly, on screen. Following the Hindu right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party’s ascend to power in 2014, Hindi cinema audiences have seen a string of mainstream releases—from Uri to Fighter to Singham Again—that depict acts of “terrorism,” against the state or its citizens, often “inspired” by real events concerning border conflicts.

The villain, we are taught in these narratives, is the ruthless Muslim, overcome with passion whether for power and land or simply a jihad that seems to require no other further explanation.

In the face of this propaganda, is the phenomenon of an increased number of old films being re-released on the big screen—Maine Pyar Kiya (1989), Rockstar (2011), Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein (2001), Tumbbad (2018). Even while all these films are readily available for streaming, the experience of arriving at the cinema hall, watching the familiar images on the big screen, and singing along to the songs we now know by heart are all packaged—with the help of social media—as nostalgic, a worthy expenditure.

The idea of nostalgia, we are told, underpins this desire to watch older stories in the cinema. As the stories return to us, we are forced to make sense of this nostalgia—in this case, for a supposedly secular and harmonious past. In her 2001 book, The Future of Nostalgia, artist and cultural theorist Svetlana Boym examines how Russian classical literature in the nineteenth century became the nation’s repository of nostalgic myths, and how popular culture in the US became the medium to spread the American way of life.

But first, she breaks down the terms—nostos (return home) and algia (longing)—as a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed. Boym points out that nostalgia is not experienced as a longing for a place but a yearning for a different time better or slower, that can be revisited like space. She also reminds us that historians often considered nostalgia to carry a negative connotation—a history without guilt, an abdication of personal responsibility.

When we celebrate the fact that two decades ago the climax of Veer Zaara was able to overturn what its protagonist laments early in the film: Veer aur Zaara ke naam kabhi saath mein nahi liya jaa sakta (Veer—a Hindu man’s name—and Zaara—a Muslim woman’s name—can never be said together), we may be missing the finer details that make up the film. Unpacking these details lets us assess whether a celebration of and a longing for the old times are well-founded.

This is perhaps why, while some Indian intellectuals mourn the end of an era that represented religious tolerance and harmony—the defeat of Hinduism against Hindutva, others point out the fallacy of this difference.

Nostalgia is Thriving With Veer Zaara

In terms of numbers, while new films are quick to reach the “300 crore club,” re-releases only average around Rs 7 crore (except for Tumbbad’s Rs 32 crore). Veer-Zaara is reported to have finally crossed the 100 crore mark through its various re-releases, the September 2024 one being the latest.

The numbers do not suggest that the re-releases are a highly profitable business model, but they certainly hint at a cultural success. In that, they not only keep the audience coming back to the cinema hall but also bring into popular circulation the stories, themes, and characters of the past. Revisiting Veer Zaara helps us see why.

As squadron leader Veer Pratap Singh (SRK) on a mission to rescue the passengers of a bus accident, saves Zaara Hayaat Khan (Preity Zinta), the young woman from Pakistan, the piano chimes in with the famous tune of Tere Liye (For You). The audience already knows the song and sings along. Whistles and hoots fill the air.

Here on, we are told repeatedly that this young man is Hindustani, with little to no reference to his religion, other than as a cultural or regional identity—in that, he seems to celebrate Lohri.

We are introduced to his land, the land of Punjab—lush green, with brimming ponds, women carrying water in their matkas, or simply running along mustard fields, and swaying on swings suspended from trees, their colorful dupattas fluttering in the wind. We even see a Radha Krishna reference with a young man playing a flute under a tree while a young woman listens in awe.

This is India, we are told, united and thriving: Dharti Sunehri, Ambar Neela (where the earth is golden and the skies are blue). This is rural India, with no sight of poverty or hunger, but where familial values keep everyone content.

After this quick summary of an entire nation that we receive through the eyes of Zaara, it is time for her to head back home. Just as Zaara is to board the train to Lahore with her fiancée, Raza, Veer confesses his love for her, leaving her confused and yearning for him. When the audience returns from the interval, Veer, who hears of Zaara’s suffering, resigns from the Indian Air Force to travel to Pakistan and fetch her.

On reaching Lahore, however, he is confronted with Zaara’s family and their desperation to protect the family honor, and her fiancée Raza’s polite rage that falsely charges him of being a spy for the Indian state. We watch as Veer, in the attempt to protect Zaara’s honor, dramatically accepts this false identity, and thus, his fate of being held in Pakistan as a political prisoner.

Veer chooses the path of quiet sacrifice that is often only attributed to women. He chooses unconditional love in the face of a vengeful Pakistani man. In this act of subversion, he tugs at the hearts of audiences. As we listen to the melancholic Do pal ruka khwabon ka karwan (This caravan of dreams stopped for just a couple of moments) when the two protagonists separate ways, we crave them to come together again.

The Language of Love, Friendship, and Peace

When Veer Zaara released in 2004, the ecosystem seemed to have allowed films to speak this language—of love, friendship, and peace between India and Pakistan. It was then possible for a man in uniform to appear in a film without wielding a single weapon and still become a hero. The ecosystem seems to have remained somewhat similar till 2010 when the Times of India and The Jang Group of Pakistan established a joint campaign named Aman ki Aasha (Hope for Peace) for diplomatic and cultural relations between the two nations.

Earlier in 2004, SRK starred in Main Hoon Na which had, in its background, Project Milaap, a fictional program of truce and reparation between the two nation-states. This time, however, the story was replete with guns, combat, and grenades, all to save the nation from its own terrorist—a Hindu man with misplaced anger. Today, these characters only come back through re-releases, as the newer big-screen releases are interested only in Pakistan-bashing.

Other elements too are unlikely to find space on the big screen today. The figure of the mother is brought up to convey that the two nations, and thus, two religions have more in common. When Veer is reminded of his mother’s cooking while eating the food his lawyer Saamia’s mother prepares, she tells him that the food prepared by mothers everywhere tastes the same. In another instance, Veer assures Zaara’s mother that he empathizes with her because “all mothers in his own country are exactly like her.”

However, critically examining the good old past is more useful than simply celebrating it. Throughout his endeavor, Veer’s identity as Sikh remains a cultural symbol, superseded by his identity as Hindustani but Zaara’s Muslim identity becomes a religious and indeed political one as her family’s electoral success hinges on her marriage. The Khanda around Veer’s neck, however, is a symbol to be reckoned with.

Today, as political tensions rise around the question of Khalistan, and global forces get deeply intertwined, how are we to read the reiteration of Veer’s identity as primarily Hindustani?

Is The Nostalgia Warranted?

In his 1998 book, Ideology of the Hindi Film, scholar Madhava Prasad stresses the significance of Film Studies and how it has been useful in defining culture as an object of study. He builds on the French philosopher Louis Althusser’s theory of ideological state apparatuses, distinguishing between direct domination and ideology.

In Marxist terms, ideology can be understood as the universalization of the particular interests of a class. It can also be understood as individuals being constituted as subjects of a social structure. This theory helps us see the state and apparatuses such as family, schools, products, and spaces of culture embodying a prevailing consensus. These apparatuses put ideologies into circulation among people.

Prasad, thus, places cultural production within the political and economic framework of the Indian nation-state. He proposes a critical reading of Indian cinema, especially popular or mainstream cinema, as a site of ideological production and reproduction of the state form. By analyzing films across decades in this framework, he demonstrates how Indian cinema, throughout its history, is related to the specificity of the socio-political formation of the Indian nation-state. Here, we witness the contestations within India over the form and character of the state.

But in the epic Indian love story that Veer Zaara is made out to be, the specific experiences of the Sikh population are ignored, and Veer’s character is incessantly called upon to represent Hindustan. In his 2021 book, Sikh Nationalism, Guharpal Singh argues that the narrative of a minority is shaped by the world around it—in this case, the world or context around the Sikh community is the rise of majority nationalism and nation-state formation.

From the time before 1947, the community became the principal “other” in the efforts of both the Congress and the Muslim League. This created a reactive minority response to autonomy and self-determination.

Singh brings attention to the official narratives by subsequent governments of India which persistently portray the regional autonomy movement in Punjab and the diaspora as “Pakistan-led,” completely neglecting the legitimacy of the demand. The co-optation of Veer as primarily and indeed only Hindustani speaks volumes of how Congress has politically managed the religious minority.

Further, as Veer performs his role as the Hindustani fighting to regain his true identity, Veer Zaara calls upon Veer’s young and yet uncorrupted lawyer, Saamia Siddiqui, to take on the male-dominant field of law in Pakistan by proving her mettle in the courtroom in her very first case. The act of highlighting patriarchy operating in the capital city, no less, of a Muslim state is cleverly juxtapositioned with a similar patriarchy only in rural Punjab 22 years in the past where the girls do not yet have a school. Painting this picture of Pakistan only reinforces the stereotype of a patriarchal public sphere in a regressive Muslim state that resists modernization.

Besides, the resolution in Veer Zaara is not just that Zaara, a Muslim woman, is claimed and brought back home by her Hindustani husband, but that the justice system in Pakistan apologizes on behalf of the state for the 22 years that it has taken away from a Hindustani. Suffice it to say the wishful thinking of the state unravels quite clearly in the court judgment.

Why Veer Zaara Still Cannot Be Made Today

Even if these observations, stacked upon one another, make it seem like the wishful thinking of a nationalist Indian government, there is some truth in the refrain that such a film cannot be made today under the current regime. Despite our critical understanding that films may have always spoken the language of the state, the feeling of loss and longing that the audience experiences has to be reconciled.

Perhaps the story of Veer and Zaara, itself premised on their longing for a lost time (with each other) is not one that the current dispensation or its ally Bollywood is interested in telling—focusing rather on exaggerated and unrealistic portrayals of the apparently unending war between the Muslim state and the Indian (Hindu) nation-state.

A cross-border love story that its makers call non-political may well be a thing of the past; an Anupam Kher may never again be forced to speak the language of peace, let alone truth and justice, between the two nations. But is there a way to make sense of the tears we still spill for this and other melodramatic tales of the 2000s?

One answer may lie in Boym’s suggestion of differentiating between restorative and reflective nostalgia. Restorative nostalgia insists it is the absolute truth and tradition, attempting to re-establish and reconstruct the lost home. According to Boym, this is the kind of nostalgia that has been at the core of national and religious revivals. This brings to mind the idea of the Ram Janmabhoomi or even the myth of Akhand Bharat, which claims that various South Asian countries are all part of a “greater India.”

Conversely, the nostalgia of the reflective kind allows thinking about the ambivalences of human longing and belonging. While restorative nostalgia protects the myth of an absolute truth, reflective nostalgia questions and presents an ethical challenge. Reflection here hints at flexibility, not the re-establishment of stasis.

“Restorative nostalgia takes itself dead seriously,” Boym writes. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, can be ironic and humorous. It reveals that longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgment, or critical reflection.”

This reflection is necessary. As Gurharpal Singh points out, Hindu nationalism has easily replaced Congress’ idea of nationalism. This compels us to rethink how the supposed secular state since 1947, and the institutional structures it created to manage religious diversity, perhaps only reinforce domination over religious minorities. This finds reflection in films too.

Perhaps, then, we can find a way to remember and reflect on the past, beyond simplistic celebration of a supposedly long-lost time. This does not mean a straight rejection of all affective responses to the old storytelling that we were once fond of, but remembering and reflecting to make important demands of the future.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.