Beyond Farm Laws: How Punjab’s farmers are building a new agricultural resistance

“Would India recognise the struggles and sacrifices of the Punjab farmers to make a decisive stand against the World Trade Organization’s agenda?” asked Sukhwinder Kaur, a veteran farm union leader. The question hung in the crisp morning air at the Punjab-Haryana border, where a two-kilometre convoy of tractors and trailers has stood parked for nearly a year, transforming the roads into a site of agrarian resistance.

The Haryana government continues to block the agitating farmers at the Punjab-Haryana border, since February 2024, ostensibly to prevent a replay of the historic, 15-month-long protest in 2020-21 at the doors of New Delhi. Now, the fate of what has come to be called the farmers’ movement 2.0, seems to be hanging in the delicate balance of a crucial, life-threatening fast resorted to by one of its leaders.

In November 2021, the first phase of the farmers’ protests ended after the Narendra Modi-led central government rolled back the three contested farm laws. Approximately a year ago, various factions within and outside the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM), the umbrella organisation that coordinated the first protest, initiated a new wave of demonstrations due to the centre being unwilling to fulfil its assurances.

The subsequent developments have led multiple SKM factions to pursue a broader coalition of farmers and labourers nationwide, to counter what they describe as the government’s alignment with global corporate interests. “The WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) caters only to the interests of imperialist monopolies, while depriving India of its economic sovereignty, and ensnaring us, farmers, to lose our autonomy as agricultural producers,” according to Sukhwinder Kaur, state general secretary of BKU (Krantikari).

As the farmers movement continued through 2024, Kaur’s village home in Rampur Phul, Bathinda, was raided in August by the National Investigation Agency (NIA). This happened while she was playing a leading role at a protest at one of the interstate borders points to enter Haryana, across the river Ghaggar, en route to Delhi. The NIA squad faced protests from a group of local BKU (Krantikari) cadres with “Go back!” slogans. Subsequently, public meetings were held in other parts of Punjab where such “diversionary tactics” of the central agency were flayed. Speakers at the gatherings called it the centre’s ploy to shield itself from the ongoing farmers movement. They said the tactic was comparable to the state’s previous attempts to portray the agitating farmers in Delhi, three years ago, as Khalistan supporters, and efforts to raise allegations connecting the SKM leadership to banned Maoist groups.

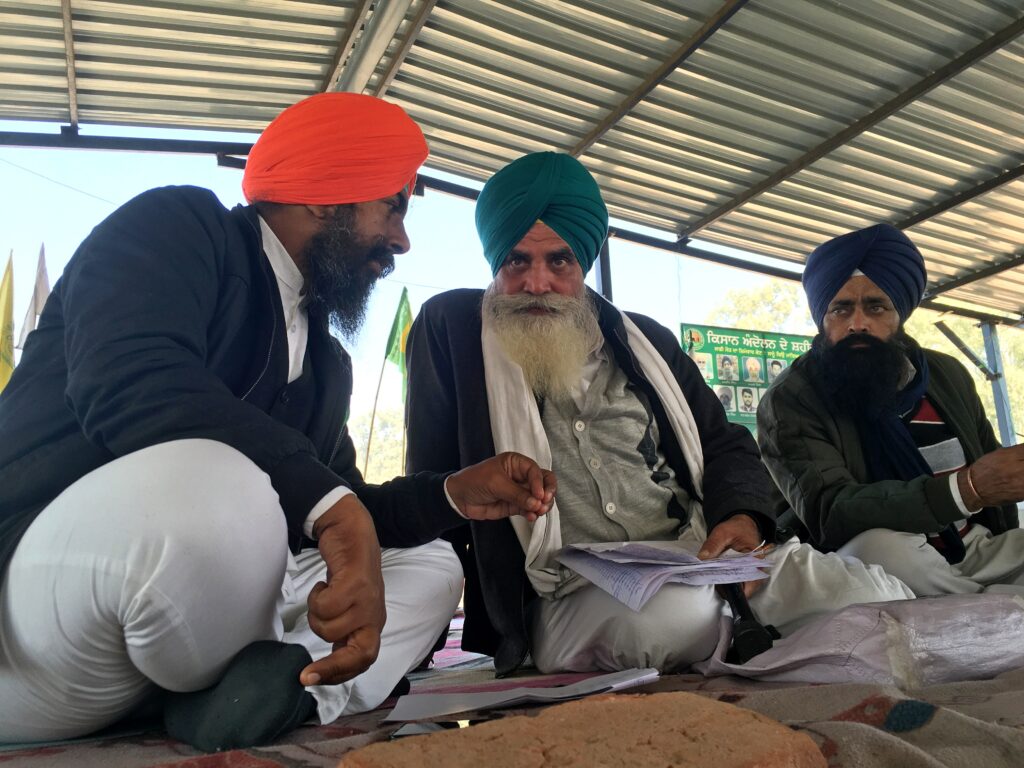

On the wintry night before Kaur spoke to The Polis Project, farmer leaders from the Shambhu and Khanauri borders, where the protesters are stationed, had conferred on the need to widen the scope of the protests. They discussed strategies beyond physical attempts at crossing the barriers created by the Haryana government to keep the farmers from getting closer to Delhi. Contingents of farmers have made multiples attempts to break through the huge metal and concrete barriers erected at Shambhu and Khanuari and backed with police and paramilitary equipped with teargas shells, water cannon and drones.

The new turn of events in the ongoing movement emerged when Jagjit Singh Dallewal, a senior peasant leader from Punjab, developed critical health indications on December 13, the 18th day of his fast-unto-death. He still keeps all medical aid at an arm’s length—even oral rehydration salts and saline drips—well into the second month of the voluntary self-sacrifice he chose to begin on November 26, 2024. The nearly 70-year-old farmer leader’s worsening condition has fuelled passions already simmering among farmers and their unions across multiple states, till Karnataka down south, regardless of differences of opinion over tactical preferences and priorities. To start his hunger strike, Dallewal chose a day, exactly nine months after a “Quit WTO” demonstration was held by his faction of the SKM, called SKM (non-political), and a sister front named Kisan Mazdoor Morcha (KMM), on the arterial roads across the north-western countryside.

Farmers’ Opposition to WTO

The farmers’ resistance to global trade pressures has deep roots in India’s complex relationship with the World Trade Organization (WTO), particularly regarding agricultural policy. The WTO has pushed its nearly 30-page Agreement of Agriculture (AoA), established at the 1995 Uruguay Round of the global General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), through its networks since the early 2000s. Over the past two decades, regardless of India’s governing party at the centre, agricultural trade policy is known to have been significantly influenced by corporate consortiums. For instance, the Australia-led Cairns Group advocates for trade liberalisation in India through WTO channels and pushes for complete AoA implementation.India’s current Minimum Support Price (MSP) system and public grain-procurement policies have faced consistent scrutiny from international trade partners. While the MSP framework nominally covers 22 crops, it is effective in Punjab primarily for wheat and paddy procurement. The government’s procurement system has historically served dual purposes: providing a buffer against crop failures and sustaining the Public Distribution System (PDS). Despite systemic failures in the PDS, it has, off and on, helped incumbents earn goodwill among the electorate during polling season. However, once the politicians are in power, such welfare schemes take a backseat as they create conflict with India’s WTO commitments under the AoA, which currently binds 166 member nations.

Farmer unions argue that the MSP regime supports autonomous crop producers, to an extent, by declaring in advance a guaranteed minimum price for a select set of crops, while the PDS subsidises food costs, particularly for the economically marginalised populace. Farm activists, especially those who participated in the 2020-2021 protests around Delhi, have now now begun to assess the intricate political economy of their countryside struggles, on the basis of their lived experiences, as well as from reports of multiple negotiations between their leaders and the centre. A common refrain at their protest sites is that as long as the centre remains tied to WTO, there would be no hope of restoring India’s national economic sovereignty with regards to agricultural policies. The protesters contend that the three farm laws, withdrawn at the end of 2021, were aligned with WTO’s push for AoA implementation and would have primarily benefited large corporate interests keen on exploiting Indian agriculture.

The battle for MSP guarantee

The demand for an MSP law has itself risen out of the sporadic and unsatisfactory implementation of a policy dating back to the early Green Revolution period, in the late 1960s. Back then, the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), under the centre’s aegis, began recommending procurement prices for crops to ensure a minimum profitability for agricultural enterprise. Subsequently, an expert committee led by agricultural scientist M S Swaminathan recommended MSPs for crops at 50% over and above all the farmers’ accountable input costs, including the costs of hired labour and family labour, depreciation of capital assets, and all rentals. The farmers have since demanded the implementation of this recommendation, abbreviated to the formula “C2+50%.”

The second phase of the farmers’ movement, which had been on the edge of erupting once again from Punjab, has drawn the centre’s disdain since the 2023 biennial meeting of WTO decision-makers. This is evident from the records of four rounds of talks held between the farmers and the centre in February 2024. The dialogue seemed prescient while it lasted, according to members of the KMM and the SKM (non-political) who spoke to The Polis Project.

However, the dialogues collapsed on February 21, when the protestors’ representatives began presenting their case to the ministerial delegation. Their topmost demand was for a legally guaranteed MSP regime for all crops—including pulses, oilseeds, cotton, along with vegetables and fruit. This demand was supported by a consistent line of rational arguments, developed from facts and figures, the members of the two unions said. The dialogue could have helped generate a fresh policy perspective, as an alternative to the “free-trade” model advanced by many experts.

During the talks with farmers, the union commerce minister Piyush Goyal proposed a scheme of five-year contracts for MSPs to procure certain pulses—lentils (masoor), black gram (urad) and pigeon peas (arhar)—along with cotton. The contracts would be administered through cooperative organisations like the National Cooperative Consumers’ Federation of India (NCCF) and the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED), but would only be available to farmers who agree to shift away from traditional paddy and wheat cultivation.

Farmer representatives rejected this conditional approach, arguing that it did not provide a framework for an MSP regime. Instead, they advocated for an unconditional MSP system that would establish transparent pricing from farm to retail, which they believe would naturally encourage a voluntary, peasant-led diversification of the cropping pattern.

The farmers’ alternative proposal to the government went against the very grain of the WTO regime. But at the same time, they proposed that universal MSP would push forward the much-mooted crop diversification, leading to the restoration of the drastically depleted ground water levels and soil quality. The farming community of Punjab has in yesteryears been led along the course of the erstwhile Green revolution policies, practised in the most intense manner in those parts than anywhere else in the country. But, as Ashok Danoda, a young activist at Khanauri, from a village in Haryana’s neighbouring Narwana sub-division, said, “The commercial gains made by farmers in these parts, through the otherwise detrimental Green Revolution policies, have accorded them the ability to comprehend, and critique the current economic practices and policies. It is one big reason why they are better qualified to propose viable alternatives, which might benefit agricultural practices and also commerce, all over the country.”

The protesting farmers made a public statement, on February 26, 2024, staging a political demonstration with the “Quit WTO” slogan, even as the 13th WTO Ministerial Conference got off to a start in Abu Dhabi. Hundreds of tractors occupied the highways in and around Punjab. Meanwhile, in Abu Dhabi, 166 governments participating in WTO failed to make any “progress” on the implementation of its agriculture agenda, much to the disappointment of the global majors.

13 demands and 3 deaths

Through two successive winters, the Haryana government has had no qualms about resorting to the use of drones and ground forces, equipped with pellet guns and tear gas shells, apart from cold water cannons, to deter farmer contingents from Shambhu or Khanauri trying to reach Delhi. During a protest on February 21, 2024, the police had resorted to such violent methods of repression, including the use of rubber bullets. On that day, a 21-year-old protestor, Shubhkaran Singh, died from a bullet wound inflicted on the Haryana side of the border at Khanauri. The postmortem report noted that Shubhkaran had died from a “firearm injury” and recorded the presence of “foreign bodies (metal pellets)” found inside his skull.

In March, the Punjab and Haryana High Court said the death appeared to be a case of excess police force. It pulled up the Punjab Police for a seven-day delay in lodging an FIR on the death of the protestor and ordered a judicial inquiry into the matter. However, the Haryana government appealed against the judicial probe, which the Supreme Court declined to stay. In September, the apex court entrusted the mediation with protesters to an empowered committee, whose effectiveness is yet to be tested.

In terms of human loss, the year-long protests have so far witnessed three deaths, including Subhkaran’s. On January 12, Joga Singh, a septuagenarian farm labourer, who was hospitalised after complaints of chest pain, passed away; he was protesting for a long time at Khanauri. In another incident, Resham Singh, a 55-year-old farmer from Punjab’s Tarn Taran district, died at a hospital in Patiala on January 9 after consuming poison at the Shambhu protest site on December 14. On the same day, a 101-strong contingent of protestors tried to cross the barricades in the last attempt to overcome the police blockade. During the confrontation, about 30 others were allegedly injured by pellet shots and tear gas shells, two of them sustaining grave eye and ear injuries.

On their part, the farmers’ unions have raised a 13-point charter of demands—the thirteenth being punitive action against the officials responsible for Shubhkaran’s death. Their other demands include the promised withdrawal of all cases registered against farmers in the course of their protests around Delhi between 2020 and 2021.

The farmer movement also seeks debt relief through loan waivers to prevent farmer suicides, while advocating for a monthly pension of Rs 10,000 for aging farmers, regardless of land ownership. Labour reforms feature prominently among the demands, with calls to increase MGNREGA wages to Rs 700 per day with 200 guaranteed workdays annually, and to integrate this rural employment programme with agricultural work to reduce farming costs. The movement also focuses on resource protection, demanding a strict enforcement of the Fifth Schedule provisions in Adivasi territories and mandatory gram sabha consent for commercial projects acquiring land and utilising local natural resources. The Fifth Schedule of the Constitution provides protective legal provisions for control over land rights as well as self-governance in predominantly Adivasi areas.

The farmers’ agenda also includes opposition to power sector privatisation through the repeal of the 2003 Electricity Act and its amendments. Additional demands focus on agricultural safeguards, including strict penalties for suppliers of counterfeit farming inputs and exemption of agricultural activities from anti-pollution regulations, arguing that industry and vehicles are the primary polluters.

However, the unions have made an MSP guarantee their primary demand as the debt crisis amid farmers and agricultural labourers has reached alarming proportions. Agrarian suicides are tied to this crisis; the National Crime Records Bureau data for 2022 indicates that at least one farmer died by suicide every hour in India.

In December 2021, following the first phase of the farmers protest, the union government had assured the SKM leadership that it would constitute a committee to consider a legislation to guarantee a universal MSP regime for all crops. The farmers now hope to contend, if given the opportunity to engage in a fresh round of talks, that such a legislation would introduce greater transparency in commerce and help stabilise erratic price fluctuations—far from fuelling inflationary trends. The farmers have cited the stable prices of rice and wheat flour despite their purchase year-after-year at government-determined MSPs. Meanwhile, market-determined, speculative commodity prices of vegetables, pulses and cooking oils have been spiralling, the representatives had pointed out in previous talks with the government.

Political nerve of the farmers’ protests

With no immediate political challenge to the current ruling dispensation, now in its third stint, the centre appears to have backtracked on the promises it made to stop the 2020-21 protests. This is precisely what led Jagjit Singh Dallewal to put his life at stake and sparked the growing unrest across farmer collectives. A mid-December letter, on behalf of Dallewal, signed with his own blood, was sent to the president of India from the Khanauri border, where the senior leader is protected by over thousand volunteers, 24-hours round the clock. The president has been urged to prevail upon the prime minister Narendra Modi to order the resumption of talks, failing which the responsibility of Dallewal’s imminent death would squarely lie on the present government. Amid this, the Supreme Court has demanded accountability from the Punjab government rather than from New Delhi.

Meanwhile, support for Dallewal’s hunger strike has deepened within Punjab, and may gradually widen across the subcontinent, according to available indications. Railway traffic has been disrupted twice across Punjab over the last month, with active support in the form of tractor marches from parts of Haryana, and an impactful, self-imposed shutdown (bandh) in the run up to the new year. Farmers’ unions—particularly Bharatiya Kisan Union (Ekta-Ugrahan), BKU (Ekta-Dakaunda), Krantikari Kisan Union, besides BKU (Krantikari), BKU (Ekta-Sidhupur), BKU (Ekta-Azad), BKU (Shahid Bhagat Singh) and Punjab Kisan Mazdoor Sangharsh Committee—have pooled in active support, each in their own respective ways, and increased coordination between factions and allies of both the SKMs.

On the occasion of Lodi and Makar Sankranti, the SKM has now also extended support to the call of KMM and SKM (non-political) to symbolically burn copies of a new agriculture marketing bill. The bill, drafted on the lines of the National Policy Framework on Agricultural Marketing, was formulated late last year by the Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare. According to SKM, the proposed reforms would bring in deregulation, allowing the private sector to dominate over production, processing. and marketing of crops.

Interestingly, the Dallewal-led faction of the Samyukt Kisan Morcha—the SKM (non-political)—was formed after one section of the original SKM, led by Balbir Singh Rajewal, broke ranks to participate in the 2022 assembly polls in Punjab, under the banner of Samyukt Samaj Morcha (SSM). The SSM drew an absolute cipher at the hustings. The original SKM, meanwhile, threw its might behind defeating the BJP, asking voters to punish it for repressing the farmers movement around Delhi. While the latter tactic may have matched with the mid-year results at parliamentary polls in Punjab and to an extent, also in Haryana, the BJP managed to swim against the anti-incumbency sentiment during Haryana assembly polls in 2024.

The pattern of farmers’ leaders venturing into electoral politics continued with Haryana’s prominent farm leader Gurnam Singh Charuni. Ahead of the assembly polls, Charuni, who heads the farm union BKU (Charuni), launched the Sanyukt Sangharsh Party. However, the party’s electoral performance proved dismal–it lost deposits in all but one constituency it contested.

One of the major contributing forces behind the BJP’s victory in Haryana was its ideological mentor, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Commenting on the BJP’s Haryana win, a senior RSS worker active in the Jind-Narwana area, told me on the condition of anonymity that the parent organisation had stepped up its anti-farmer unions propaganda to move away the people of Haryana from the voting trend in Punjab. Presenting a snippet from the electoral propaganda campaign, he alleged that the farmers’ movement was painted as “anti-national” and run by “enemies” across the Line of Control or LoC. The central anti-terror agency, NIA, also launched its first anti-Maoist raid across Punjab and Haryana on August 30, giving an upper hand to the pre-poll strategies of the BJP-RSS squad.

Against the backdrop of the long prevailing uncertainty and consequent tension over how Dallewal’s health plays out, with his hunger strike scheduled to complete two months just before Republic Day, the original SKM, too, has announced its general and executive body meetings, at Delhi, around that time. The future course of the broadening farmers’ movement 2.0 would hopefully emerge with some form of closer coordination not only between the stable allies of each of the two SKMs functioning independently, but between the two SKMs themselves. Mass rallies of peasants and farm workers held at Tohna in Haryana and Moga in Punjab, in January this year, indicate the struggle-readiness of both these leading forces of northern India’s farming community.