An empty ancestral home—little more than a mud hut now—was transformed into a space of discovery and creative synthesis in February 2021. Each day, a different folk group from the Nimad region of Madhya Pradesh would show up with their musical gear. These artists, carrying with them the folk stories and songs of their ancestors, had been invited to this space by Bharat Chandore and Jayesh Malani, two musicians trained primarily in Western disciplines who had arrived from Barwani and Mumbai respectively. They would chit-chat and exchange notes on their divergent musical traditions over endless cups of tea. They’d jam together and collaborate on songs to record.

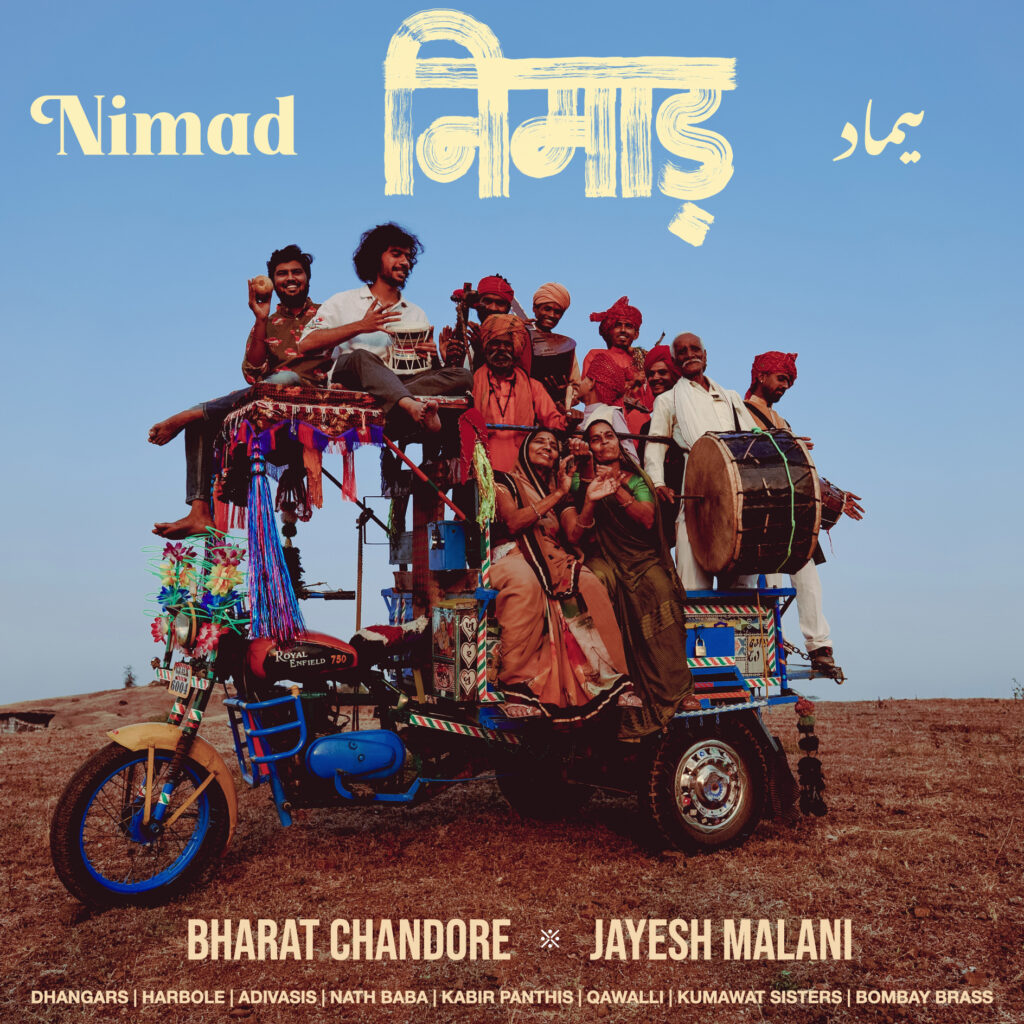

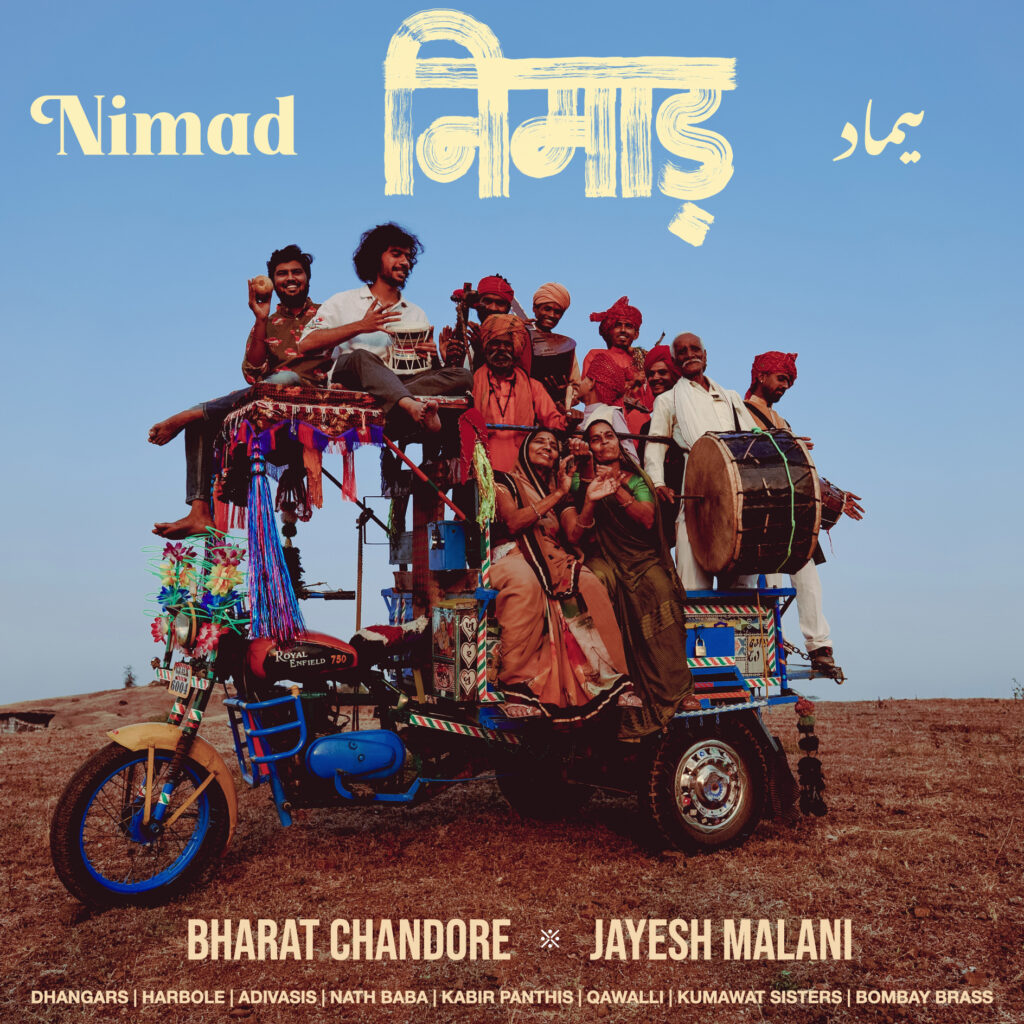

Now, three years later, the group is releasing a new eight-song record called Nimad, which materialized during this period.

Most of Nimad was recorded at Chandore’s ancestral house, deep inside rural Madhya Pradesh, in a village by the Narmada River bank called Chichli, which the duo converted into a makeshift recording studio. Nimad is a folk-fusion album that maintains the local musical traditions at its core, which Chandore and Malani have embellished and amplified with motifs from jazz, rock, and the blues. Three singles—including the magnetic “Harbola Blues”—have already been released. The music is full of life and color, sometimes whimsical and playful, frequently electric. It has a wandering spirit—spanning several local traditions—with a sense of curiosity, wonder, and nostalgia.

![Bharat Chandore’s ancestral home in Chichli, a village by the Narmada River bank, was little more than a mud hut when the musicians arrived. (Photo by Aakash Meshram [L] and Jayesh Malani [R])](https://thepolisproject.com//srv/htdocs/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Untitled-design-1.png)

The duo are composers and multi-instrumentalists, with Chandore primarily trained as a drummer while Malani plays the guitar. They met at Mumbai’s True School of Music in 2017, and have remained friends since. In addition to the record, Chandore and Malani have also put together a photo series, music videos, and an elaborate, theatrical audio-visual live performance called Nimad: Under the Neem Tree, which premiered in October 2023 in Mumbai. The live show incorporates narrative storytelling and documentation of Nimad, with a visual storyline, projection mapping, and light display, all supporting the music. This is an attempt to bring audiences to Nimad and connect them to the musicians who tell its stories.

The project began to take root in November 2020. Chandore had moved back during the early COVID-19 days from Mumbai to his hometown, Barwani in Madhya Pradesh. “My childhood was around Nimadi folk music, and I was very influenced by it. I thought: ‘Why not record the folk artists and explore this music while I’m here?’” he told me. “So I started asking around and exploring what folk groups there are here [and] what kind of music they do.”

27-year-old Balkrishna Dhangar, who is featured on the album, told me how someone who worked as a driver in Barwani told Chandore about them. “The driver knew us well; he knew that we did akashwani programs [radio broadcasts] and other shows. He told Bharat bhai, ‘These two boys [Balkrishna and his brother Lalkrishna] sing well about Nimadi culture.’ He came and met us. We spoke for a long time over tea and snacks. We didn’t know what exactly he was looking for, but we thought: ‘You want to hear us sing, we’ll sing!’”

Chandore sent videos from his travels to Malani, who was in Mumbai then, hoping his and Malani’s plans to collaborate together would come true. After all, the two shared a nonconformist attitude to music. And it did.

Conceptualizing Nimad

The duo spent the next two or three months scouting, learning about groups and folk traditions in the region. “[Chandore] was traveling with his drum kit in the car,” said Malani. “Wahan jaa ke mehfil ban jaati thi. It would turn into an impromptu musical gathering and people would stand around and watch.”

Chandore would jam, record, and share the videos with Malani. They would then discuss what they found interesting. Primarily, the plan was to document the musicians from Nimad. “And to, like, jam with them and see what happens,” Malani added. “It was never, ‘Let’s make a “fusion” record.’ It was very intuitive that way.”

The duo were clear they didn’t want the polished folk-fusion sound that has become popular in the urban Indian mainstream consciousness over the last two decades, often heard on the TV series Coke Studio and at music festivals in India. This type of slick, carefully designed “east-meets-west” fusion can, at its best, highlight the wonderful collision between contrasting musical forms. When it falters, though, it can seem like the Indian sounds are little more than a vessel for novelty within a Western framework.

“Nothing bad to say about it,” said Malani, “I grew up listening to that music. But we wanted the raw essence—that is breathing, has energy.” To give an idea of their underlying vision, he cited the examples of the Buena Vista Social Club and Junun, the album recorded in a fort in Jodhpur by Shye Ben Tzur, Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, and a group of Indian musicians who would later christen themselves Rajasthan Express. Many artists Chandore and Malani worked with are practitioners of dying musical forms. They’re the last generation still playing this music, Malani told me, “preserving a form that has been passed on generationally.”

The album features a range of diverse traditions and artists from the Nimad region. These include Deepak and Bhola of the Harbola group from the Malwa region; an Adivasi group of musicians from a neighboring village, who play a native style of percussion at local festive occasions; Bichhonath Baba, belonging to the Nath Babas who are Kabir panthis (they follow the teachings of Saint Kabir and sing his couplets); Dashrath Bhandole, or Dashrath Dada—who plays the traditional festive drum called the Chichli Dhol—Lalkrishna and Balkrishna Dhangar, who sing of pastoral life and the local cultural traditions; and the Kumawat sisters along with many women from the Chichli village, who have sung a prayer of invitation to deceased ancestors, a local tradition in the region, on the song “Saragbhavanti”.

Dashrath Dada plays the Chichli Dhol and is one of the only people preserving and carrying forth this particular native drumming style. The Harbolas, Malani told me, were the “OG rappers,” traveling from village to village since well before India’s Independence in 1947, “singing the news.” With them, Chandore and Malani have worked on a song called “Harbola Blues,” which has a swaying, New Orleans-style rhythm section and a six-piece brass section, performed by Bombay Brass. The lyrics are metatextual, with the Harbolas documenting the duo’s journey of working with Nimadi musicians and making music.

“We sing Nimadi lokgeet (folk songs) that the farmer community in our region, our elders and ancestors, sang,” said Balkrishna Dhangar, who is from Dawana village in Nimad and works as a farmer while his brother is a teacher “That culture, that sanskriti, that music that we have learnt from them.” He explained that their music has traditionally been sung at local festivals, such as gangaur, on celebratory occasions, and during wedding rituals such as the farewell of the bride or the haldi ceremony, where the bride and groom are adorned with turmeric.

“Our pitr (ancestors) who’ve passed on and are no longer among us…there is this faith that remains in our soul that we can reach them through the medium of song,” added Dhangar. “The women in our families sit together and sing to them, believing that they manifest as the wind and join us at this moment—hawa ke roop mein woh humare beech maujood hain.”

Their music is also a tribute to Nimad and their pastoral life. “We are anxious that our culture may die,” Dhangar said, “and so we’re playing our music and informing people about it.” Beyond the songs they have inherited from their ancestors, the Dhangar musicians of Nimadhave also composed new music, seeking to keep the form alive.

While Nimad was primarily conceived of, composed, and recorded in Chichli, Chandore and Malani also worked with a few artists separately, including Mumbai’s Bombay Brass, Saurabh Suman, Navaneeth Venkateshwar, Deepak Yadav, Vishal Singh, as well as the Aftab Qadri Qawwal Party from Indore, one of the few in the country to practice Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s school of qawwali.

Producing Nimad

Recording the album was an adventure of its own. Chandore and Malani got to Chichli in February 2021—along with Akshat Vijaywargiya who was shooting with them, and Deepak Yadav, who appeared on the album and helped with engineering and logistics.

“So what’s happened,” Malani explained, “is that Chichli comes under what is called doobkshetra [flood-prone area]. It can get flooded because of the Narmada River. So the government has shifted the entire village a kilometer or two away from the bank. That’s the new Chichli.” Chandore’s ancestral house, however, is situated in the old region, which is now largely deserted except for a few inhabitants. The rest have moved to the new village.

Chandore’s family home, a mud house with a huge banyan tree outside, was pretty much abandoned. They set up the studio in a room upstairs, borrowing rugs for acoustic softening and soundproofing from nearby village residents. “We got electricity wires connected—there were no bulbs even—and made it into a nice, proper studio,” Malani said. “We carried a table, our speakers, everything.” The process took them half a day.

Every day for the next ten days, a new group of folk musicians came in to record. Balkrishna Dhangar explained that the duo had asked them a few times to collaborate with them. “I keep going to Chichli often,” he shared. “They said, ‘Bhaiya (brother), do come and record with us.’ We were busy in our village and didn’t have time to spare but we decided to go. Once we went there, we met Jayesh bhai and recorded with them, and did some videography as well. We knew that it would expand from there.”

The artists, Malani explained, would travel from all parts of Nimad to Chichli. “Sometimes from the villages around us, or from 150-200 kilometers away,” he said. “They’d come on a bike or a bus or even in that Toofan vehicle! The Indian Hummer that can fit, like, 10-12 people.”

Upon arrival, the two would try to forge a personal connection with the artists. “We’d chat, have some chai, ask if they’ve eaten, get to know them,” Malani added. “What is the practice they’re preserving; how they make a living. Ask about their music. Connect with them on a human level.” Once everyone felt comfortable with each other, they’d shift upstairs to record with them.

This period was perhaps the most rewarding for the duo. They recorded in the day with the folk artists and developed these recordings well into the night. They took a non-traditional approach to the entire process and would allow for the artists’ personal sensibilities to dictate the proceedings. “For example,” Malani explained, “you can’t ask a folk musician to put on headphones and give them a metronome to play to. They work on their own rhythm, based on the sarangi or the tambori. It’s different with different groups.”

One group, he told me, had a large number of people, and so they recorded in the open, stationing the artists at different spots in the area based on the volume of their instruments and positioning microphones at different spots. With another group, once they started jamming, the contrasting sounds of the instruments seemed to rub against each other. They figured that the dissonance was because every instrument belonging to the folk artists was tuned to a harmonium.

“And their harmonium, which was very old, was detuned!” Malani said. In other words, the folk instruments were in tune with each other and sounded fine when played together. But set against the guitars, there was a clash. So Malani and Chandore re-tuned their instruments to a different frequency entirely, to record the album prelude, “Dhanya Dhanya Nimad,” and the opener, “Pyaro Pyaro.”

“Through these 10 days, there were a lot of magical moments that we were almost gifted—some from the folk artists, some from us that we manifested in a way,” said Malani. “We knew this was something really special.”

Almost the entire album was arranged and recorded during this period. “We did it in one go,” said Chandore. “We wanted to keep that feeling—of Chichli—in the album.” In one song, “Guru Gyaan,” there’s a guitar solo for which they’ve used the very first take. “If we were recording in Mumbai in a studio, it would have been like 12 takes,” Chandore said. “And we’d have sat on it later to analyze it, to cut and chop it, to make it ‘perfect’. We knew we could have made it more ‘polished’, but we wanted to keep that essence of the place.”

They did, however, go back to record additional parts and to play around with the structure and arrangements on a couple of the songs—“Chichli Dhol” and “Saragbhavanti”—adding a grander, more cinematic quality to them, in contrast to the more rooted, stripped-down pastoral quality of the other songs.

By May 2022, they were done. That’s when they contacted Ben Findlay, respected mixing and mastering engineer who has worked on the production of the likes of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Thin Lizzy, Jeff Beck, and Peter Gabriel.

After six months of back and forth, Nimad was mixed, mastered, and ready to go. They had their record.

Visualizing Nimad

“In my head, the visual and the aural are the same thing,” said Malani, who is also a filmmaker and likes to work with a clear visual identity for his music. “Both of them function together to tell the story.” Using footage from their initial time at Chichli, he cut a trailer that would go on to inform the visual aesthetic of their work.. Malani wanted the music, visuals, videos, photos, texts, and even fonts to reflect that one unifying identity.

Keerthi Raju, a filmmaker living in Mumbai, came on board to direct a music video for “Chichli Dhol” and “Guru Gyaan.” She is also their concert visuals director and has directed all the footage for the live show. She traveled to Chichli in the summer of 2023 with Malani and a small crew to shoot live footage. Raju spoke fondly of the experience of visiting Nimad. “The tone of Nimad came set already,” she told me. “There are cinematic elements to it and a real story. It’s very picturesque, with a small community. You can’t help but capture them as they are.” For texture and detail, she focussed on the water body, the local customs, and the people.

Around the same time, the duo were in discussions with Warren de Sylva, a writer and theater director who has been involved in folk music for many years. “They had all this footage, they had the music, and were looking at what to do for a live show,” said de Sylva. “My thought was that this is not just a band performance; I see it as an audio-visual immersive experience.” De Sylva came on board as the director for the live show in April 2023, and they started crafting a narrative they could present to audiences.

He wanted to create a “live documentary” of Nimad—a mix, in his words, of “live music, artists talking about the music and the traditions of the instruments they’ve been playing for decades; something that gives you insight into the group and their traditions even as you’re watching the live recreation of it.” That became the starting point of an audio-visual documentary, connecting the visual journey to each song and creating a storyline behind it.

Instead of waiting for a gig to appear, de Sylva insisted they book a venue and premier the show themselves. And thus, on October 27, 2023, Nimad: Under the Neem Tree opened at the St. Andrew’s Auditorium in Mumbai. Balkrishna Dhangar spoke of how this was his first time in Mumbai. “Shandaar tha (the performance was fantastic),” he said. “We traveled the city and had a blast. We all felt this could go even further.”

In the time since, they’ve had a handful of gigs, and intend to start touring with the setup soon. The lineup for the live show includes the Dhangars, the Harbolas, Dashrath Dada, Chandore and Malani, and many others. The idea, de Sylva explained, was to highlight the folk artists as the show’s heroes. “A lot of the artists remain unknown,” he said, expressing concerns over how folk music is sometimes perceived. “They remain support functions to a live band or DJ who’s collaborating. The bill would say, ‘XYZ featuring Rajasthani musicians.’”

The Nimad project attempts to invert that bill. Instead of the Western musicians imposing their idiom on folk artists, whose sensibilities are curtailed, modified, and stage-managed, the primary focus here is on the folk traditions of Nimad, with everything else working in service of that central identity.

Ambitiously, the entire show is directed in real-time, with the visuals, the projection mapping onto a scrim to give an effect of layering, lights, and visual changes, all taking place even as the music takes centerstage and the stories of Nimad and its artists run alongside. If the musicians go on for a few bars longer or indulge in a jugalbandi (impromptu jam), the live direction adapts accordingly, with an entire crew working in real time.

“What I believe is: the audience is neither a monolith nor narrow-minded,” Balkrishna Dhangar told me. “Someone in the crowd may only enjoy Western music. For someone else, the story of Nimad might touch their soul. A third person may not understand either.”

“But we have the videos behind us, they can see what we’re singing about, what we’re trying to tell them,” he added: “What the stories of Nimad are.”

Project Nimad: A Folk-Fusion Album With Local Musical Traditions At Its Core

An empty ancestral home—little more than a mud hut now—was transformed into a space of discovery and creative synthesis in February 2021. Each day, a different folk group from the Nimad region of Madhya Pradesh would show up with their musical gear. These artists, carrying with them the folk stories and songs of their ancestors, had been invited to this space by Bharat Chandore and Jayesh Malani, two musicians trained primarily in Western disciplines who had arrived from Barwani and Mumbai respectively. They would chit-chat and exchange notes on their divergent musical traditions over endless cups of tea. They’d jam together and collaborate on songs to record.

Now, three years later, the group is releasing a new eight-song record called Nimad, which materialized during this period.

Most of Nimad was recorded at Chandore’s ancestral house, deep inside rural Madhya Pradesh, in a village by the Narmada River bank called Chichli, which the duo converted into a makeshift recording studio. Nimad is a folk-fusion album that maintains the local musical traditions at its core, which Chandore and Malani have embellished and amplified with motifs from jazz, rock, and the blues. Three singles—including the magnetic “Harbola Blues”—have already been released. The music is full of life and color, sometimes whimsical and playful, frequently electric. It has a wandering spirit—spanning several local traditions—with a sense of curiosity, wonder, and nostalgia.

![Bharat Chandore’s ancestral home in Chichli, a village by the Narmada River bank, was little more than a mud hut when the musicians arrived. (Photo by Aakash Meshram [L] and Jayesh Malani [R])](https://thepolisproject.com//srv/htdocs/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Untitled-design-1.png)

The duo are composers and multi-instrumentalists, with Chandore primarily trained as a drummer while Malani plays the guitar. They met at Mumbai’s True School of Music in 2017, and have remained friends since. In addition to the record, Chandore and Malani have also put together a photo series, music videos, and an elaborate, theatrical audio-visual live performance called Nimad: Under the Neem Tree, which premiered in October 2023 in Mumbai. The live show incorporates narrative storytelling and documentation of Nimad, with a visual storyline, projection mapping, and light display, all supporting the music. This is an attempt to bring audiences to Nimad and connect them to the musicians who tell its stories.

The project began to take root in November 2020. Chandore had moved back during the early COVID-19 days from Mumbai to his hometown, Barwani in Madhya Pradesh. “My childhood was around Nimadi folk music, and I was very influenced by it. I thought: ‘Why not record the folk artists and explore this music while I’m here?’” he told me. “So I started asking around and exploring what folk groups there are here [and] what kind of music they do.”

27-year-old Balkrishna Dhangar, who is featured on the album, told me how someone who worked as a driver in Barwani told Chandore about them. “The driver knew us well; he knew that we did akashwani programs [radio broadcasts] and other shows. He told Bharat bhai, ‘These two boys [Balkrishna and his brother Lalkrishna] sing well about Nimadi culture.’ He came and met us. We spoke for a long time over tea and snacks. We didn’t know what exactly he was looking for, but we thought: ‘You want to hear us sing, we’ll sing!’”

Chandore sent videos from his travels to Malani, who was in Mumbai then, hoping his and Malani’s plans to collaborate together would come true. After all, the two shared a nonconformist attitude to music. And it did.

Conceptualizing Nimad

The duo spent the next two or three months scouting, learning about groups and folk traditions in the region. “[Chandore] was traveling with his drum kit in the car,” said Malani. “Wahan jaa ke mehfil ban jaati thi. It would turn into an impromptu musical gathering and people would stand around and watch.”

Chandore would jam, record, and share the videos with Malani. They would then discuss what they found interesting. Primarily, the plan was to document the musicians from Nimad. “And to, like, jam with them and see what happens,” Malani added. “It was never, ‘Let’s make a “fusion” record.’ It was very intuitive that way.”

The duo were clear they didn’t want the polished folk-fusion sound that has become popular in the urban Indian mainstream consciousness over the last two decades, often heard on the TV series Coke Studio and at music festivals in India. This type of slick, carefully designed “east-meets-west” fusion can, at its best, highlight the wonderful collision between contrasting musical forms. When it falters, though, it can seem like the Indian sounds are little more than a vessel for novelty within a Western framework.

“Nothing bad to say about it,” said Malani, “I grew up listening to that music. But we wanted the raw essence—that is breathing, has energy.” To give an idea of their underlying vision, he cited the examples of the Buena Vista Social Club and Junun, the album recorded in a fort in Jodhpur by Shye Ben Tzur, Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, and a group of Indian musicians who would later christen themselves Rajasthan Express. Many artists Chandore and Malani worked with are practitioners of dying musical forms. They’re the last generation still playing this music, Malani told me, “preserving a form that has been passed on generationally.”

The album features a range of diverse traditions and artists from the Nimad region. These include Deepak and Bhola of the Harbola group from the Malwa region; an Adivasi group of musicians from a neighboring village, who play a native style of percussion at local festive occasions; Bichhonath Baba, belonging to the Nath Babas who are Kabir panthis (they follow the teachings of Saint Kabir and sing his couplets); Dashrath Bhandole, or Dashrath Dada—who plays the traditional festive drum called the Chichli Dhol—Lalkrishna and Balkrishna Dhangar, who sing of pastoral life and the local cultural traditions; and the Kumawat sisters along with many women from the Chichli village, who have sung a prayer of invitation to deceased ancestors, a local tradition in the region, on the song “Saragbhavanti”.

Dashrath Dada plays the Chichli Dhol and is one of the only people preserving and carrying forth this particular native drumming style. The Harbolas, Malani told me, were the “OG rappers,” traveling from village to village since well before India’s Independence in 1947, “singing the news.” With them, Chandore and Malani have worked on a song called “Harbola Blues,” which has a swaying, New Orleans-style rhythm section and a six-piece brass section, performed by Bombay Brass. The lyrics are metatextual, with the Harbolas documenting the duo’s journey of working with Nimadi musicians and making music.

“We sing Nimadi lokgeet (folk songs) that the farmer community in our region, our elders and ancestors, sang,” said Balkrishna Dhangar, who is from Dawana village in Nimad and works as a farmer while his brother is a teacher “That culture, that sanskriti, that music that we have learnt from them.” He explained that their music has traditionally been sung at local festivals, such as gangaur, on celebratory occasions, and during wedding rituals such as the farewell of the bride or the haldi ceremony, where the bride and groom are adorned with turmeric.

“Our pitr (ancestors) who’ve passed on and are no longer among us…there is this faith that remains in our soul that we can reach them through the medium of song,” added Dhangar. “The women in our families sit together and sing to them, believing that they manifest as the wind and join us at this moment—hawa ke roop mein woh humare beech maujood hain.”

Their music is also a tribute to Nimad and their pastoral life. “We are anxious that our culture may die,” Dhangar said, “and so we’re playing our music and informing people about it.” Beyond the songs they have inherited from their ancestors, the Dhangar musicians of Nimadhave also composed new music, seeking to keep the form alive.

While Nimad was primarily conceived of, composed, and recorded in Chichli, Chandore and Malani also worked with a few artists separately, including Mumbai’s Bombay Brass, Saurabh Suman, Navaneeth Venkateshwar, Deepak Yadav, Vishal Singh, as well as the Aftab Qadri Qawwal Party from Indore, one of the few in the country to practice Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s school of qawwali.

Producing Nimad

Recording the album was an adventure of its own. Chandore and Malani got to Chichli in February 2021—along with Akshat Vijaywargiya who was shooting with them, and Deepak Yadav, who appeared on the album and helped with engineering and logistics.

“So what’s happened,” Malani explained, “is that Chichli comes under what is called doobkshetra [flood-prone area]. It can get flooded because of the Narmada River. So the government has shifted the entire village a kilometer or two away from the bank. That’s the new Chichli.” Chandore’s ancestral house, however, is situated in the old region, which is now largely deserted except for a few inhabitants. The rest have moved to the new village.

Chandore’s family home, a mud house with a huge banyan tree outside, was pretty much abandoned. They set up the studio in a room upstairs, borrowing rugs for acoustic softening and soundproofing from nearby village residents. “We got electricity wires connected—there were no bulbs even—and made it into a nice, proper studio,” Malani said. “We carried a table, our speakers, everything.” The process took them half a day.

Every day for the next ten days, a new group of folk musicians came in to record. Balkrishna Dhangar explained that the duo had asked them a few times to collaborate with them. “I keep going to Chichli often,” he shared. “They said, ‘Bhaiya (brother), do come and record with us.’ We were busy in our village and didn’t have time to spare but we decided to go. Once we went there, we met Jayesh bhai and recorded with them, and did some videography as well. We knew that it would expand from there.”

The artists, Malani explained, would travel from all parts of Nimad to Chichli. “Sometimes from the villages around us, or from 150-200 kilometers away,” he said. “They’d come on a bike or a bus or even in that Toofan vehicle! The Indian Hummer that can fit, like, 10-12 people.”

Upon arrival, the two would try to forge a personal connection with the artists. “We’d chat, have some chai, ask if they’ve eaten, get to know them,” Malani added. “What is the practice they’re preserving; how they make a living. Ask about their music. Connect with them on a human level.” Once everyone felt comfortable with each other, they’d shift upstairs to record with them.

This period was perhaps the most rewarding for the duo. They recorded in the day with the folk artists and developed these recordings well into the night. They took a non-traditional approach to the entire process and would allow for the artists’ personal sensibilities to dictate the proceedings. “For example,” Malani explained, “you can’t ask a folk musician to put on headphones and give them a metronome to play to. They work on their own rhythm, based on the sarangi or the tambori. It’s different with different groups.”

One group, he told me, had a large number of people, and so they recorded in the open, stationing the artists at different spots in the area based on the volume of their instruments and positioning microphones at different spots. With another group, once they started jamming, the contrasting sounds of the instruments seemed to rub against each other. They figured that the dissonance was because every instrument belonging to the folk artists was tuned to a harmonium.

“And their harmonium, which was very old, was detuned!” Malani said. In other words, the folk instruments were in tune with each other and sounded fine when played together. But set against the guitars, there was a clash. So Malani and Chandore re-tuned their instruments to a different frequency entirely, to record the album prelude, “Dhanya Dhanya Nimad,” and the opener, “Pyaro Pyaro.”

“Through these 10 days, there were a lot of magical moments that we were almost gifted—some from the folk artists, some from us that we manifested in a way,” said Malani. “We knew this was something really special.”

Almost the entire album was arranged and recorded during this period. “We did it in one go,” said Chandore. “We wanted to keep that feeling—of Chichli—in the album.” In one song, “Guru Gyaan,” there’s a guitar solo for which they’ve used the very first take. “If we were recording in Mumbai in a studio, it would have been like 12 takes,” Chandore said. “And we’d have sat on it later to analyze it, to cut and chop it, to make it ‘perfect’. We knew we could have made it more ‘polished’, but we wanted to keep that essence of the place.”

They did, however, go back to record additional parts and to play around with the structure and arrangements on a couple of the songs—“Chichli Dhol” and “Saragbhavanti”—adding a grander, more cinematic quality to them, in contrast to the more rooted, stripped-down pastoral quality of the other songs.

By May 2022, they were done. That’s when they contacted Ben Findlay, respected mixing and mastering engineer who has worked on the production of the likes of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Thin Lizzy, Jeff Beck, and Peter Gabriel.

After six months of back and forth, Nimad was mixed, mastered, and ready to go. They had their record.

Visualizing Nimad

“In my head, the visual and the aural are the same thing,” said Malani, who is also a filmmaker and likes to work with a clear visual identity for his music. “Both of them function together to tell the story.” Using footage from their initial time at Chichli, he cut a trailer that would go on to inform the visual aesthetic of their work.. Malani wanted the music, visuals, videos, photos, texts, and even fonts to reflect that one unifying identity.

Keerthi Raju, a filmmaker living in Mumbai, came on board to direct a music video for “Chichli Dhol” and “Guru Gyaan.” She is also their concert visuals director and has directed all the footage for the live show. She traveled to Chichli in the summer of 2023 with Malani and a small crew to shoot live footage. Raju spoke fondly of the experience of visiting Nimad. “The tone of Nimad came set already,” she told me. “There are cinematic elements to it and a real story. It’s very picturesque, with a small community. You can’t help but capture them as they are.” For texture and detail, she focussed on the water body, the local customs, and the people.

Around the same time, the duo were in discussions with Warren de Sylva, a writer and theater director who has been involved in folk music for many years. “They had all this footage, they had the music, and were looking at what to do for a live show,” said de Sylva. “My thought was that this is not just a band performance; I see it as an audio-visual immersive experience.” De Sylva came on board as the director for the live show in April 2023, and they started crafting a narrative they could present to audiences.

He wanted to create a “live documentary” of Nimad—a mix, in his words, of “live music, artists talking about the music and the traditions of the instruments they’ve been playing for decades; something that gives you insight into the group and their traditions even as you’re watching the live recreation of it.” That became the starting point of an audio-visual documentary, connecting the visual journey to each song and creating a storyline behind it.

Instead of waiting for a gig to appear, de Sylva insisted they book a venue and premier the show themselves. And thus, on October 27, 2023, Nimad: Under the Neem Tree opened at the St. Andrew’s Auditorium in Mumbai. Balkrishna Dhangar spoke of how this was his first time in Mumbai. “Shandaar tha (the performance was fantastic),” he said. “We traveled the city and had a blast. We all felt this could go even further.”

In the time since, they’ve had a handful of gigs, and intend to start touring with the setup soon. The lineup for the live show includes the Dhangars, the Harbolas, Dashrath Dada, Chandore and Malani, and many others. The idea, de Sylva explained, was to highlight the folk artists as the show’s heroes. “A lot of the artists remain unknown,” he said, expressing concerns over how folk music is sometimes perceived. “They remain support functions to a live band or DJ who’s collaborating. The bill would say, ‘XYZ featuring Rajasthani musicians.’”

The Nimad project attempts to invert that bill. Instead of the Western musicians imposing their idiom on folk artists, whose sensibilities are curtailed, modified, and stage-managed, the primary focus here is on the folk traditions of Nimad, with everything else working in service of that central identity.

Ambitiously, the entire show is directed in real-time, with the visuals, the projection mapping onto a scrim to give an effect of layering, lights, and visual changes, all taking place even as the music takes centerstage and the stories of Nimad and its artists run alongside. If the musicians go on for a few bars longer or indulge in a jugalbandi (impromptu jam), the live direction adapts accordingly, with an entire crew working in real time.

“What I believe is: the audience is neither a monolith nor narrow-minded,” Balkrishna Dhangar told me. “Someone in the crowd may only enjoy Western music. For someone else, the story of Nimad might touch their soul. A third person may not understand either.”

“But we have the videos behind us, they can see what we’re singing about, what we’re trying to tell them,” he added: “What the stories of Nimad are.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.