Kirsty Mackay On Centering Agency and Empathy To Photograph the UK’s Cost of Living Crisis

Kirsty Mackay has been photographing since age sixteen and identifies as a photographic artist, educator, activist, and filmmaker. In 2016, she received an honorable mention for the UNICEF Photo of the Year Award, and her work is regularly discussed in major online media, with TIME Magazine calling her a female photojournalist “worthy of recognition” in 2017. She’s often exhibiting within the UK, while, further afield, her work has also been featured in India, Italy, and Germany. She’s been to Paris Photo this year while touring her latest exhibition.

Despite her international success, the artist is strongly connected to her Scottish roots, with her politically-edged work centered on British working-class voices. The Glasgow-born photographer grew up working-class in Partick, Scotland—once saying that seeing the disparity between a more affluent neighboring suburb helped her be class conscious from a young age. She pursued photography at Glasgow College, before relocating to New York and London as a photography assistant to several well-known practitioners. She gained an MA in documentary photography and, ever since, has centered injustice in her work, calling out current dogmatic policies while being informed by her past, cognisant of the impact and long-lasting effects of social inequality.

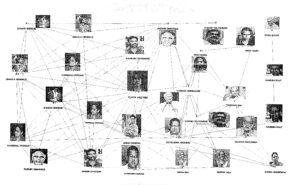

As such, photography is just one part of Mackay’s expansive, socially driven projects, which she develops over long periods with a personable, research-led process. Mackay spends extended time in communities for her projects to form relationships and collect stories. In The Magic Money Tree, her latest project released this October, she continues to turn to poverty and discrimination in the UK, exploring the cost of living crisis across South Bristol (where Mackay lives), Tipton in The Black Country (West Midlands), and South Shields in the North East. The project exists as both an exhibition touring the UK this year, about the cost of living crisis in 2023, and a photo book examining its larger context.

In creating The Magic Money Tree, she would visit homes and community centers many times, sometimes not asking questions or taking photos, to let people connect with her at their own pace. She was assured that letting them lead the relationship would cultivate trust and, perhaps, if they were open to it, eventuate in photos or interviews for the book—as such, her material centers the subjects’ agency so much that it’s a theme in itself.

For instance, she spent a month visiting a food bank; instead of photographing the people inside, she captured bus shelters and pavements inscribed with quotes from their experiences, which form part of the book. She also spent extensive time in the home of 38-year-old mum Leighanne, with the book featuring an image with a quote from Mackay saying, “She shows me a photo on her phone. It’s a picture of her hugging him. He is now adopted. “I had nothing, I gave him up for adoption. If I’d had support, I could have kept him.””

In the book’s final pages, Mackay returns to Leighanne’s at Christmastime as she celebrates at home with her two eldest children. As a result, the book and its accompanying exhibition are devoid of the superficiality or patronization that can often be present in the work with marginalized populations. The core theme is dignity: she captures communities in their complexities and seasons.

Collaborative and personal processes are key to her practice. Mackay could spend such a critically drawn-out time developing relationships because of an Arts Council grant–– a case for fairly funding artists, especially photographers dealing with people, so that they have space and time to create deep, meaningful, and ethical work.

But as she concentrates on people to explore the causes and outcomes of poverty, Mackey never blames individuals—political policy is always the antagonist. In her previous book, The Fish That Never Swam (2021), she gathered first-person accounts in Glasgow, Scotland, placing their photographs between a research paper by NHS Scotland and The Glasgow Centre for Population Health about health inequalities as a direct cause of policy: the report found that, due to poverty and inequality, Glaswegians experience 15% reduction in life expectancy compared to other regions in the United Kingdom.

Similarly, in The Magic Money Tree, Mackay intersperses her photography with texts in the form of transcripts and quotes that speak to discriminatory political decision-making driving the cost of living crisis. Driven by high household energy bills, inflating food prices, and stagnant wages, the crisis has exacerbated the precarity and strain low-income communities already face.

In the UK, this has led to a 61% increase in the most extreme form of poverty between 2019 and 2022, with one in five people living in poverty and 4.2 million children affected. In 2024, these statistics are likely to be more dire. As one of her interviewees in the book said, “This is not a low-income issue”; a significant portion of the population is at risk, and political leaders are accountable.

As much as the book is empathetic to the people it represents, Mackay is serious about the urgent role of politics, outlining how decades-in-the-making conditions have made Brits vulnerable to widespread poverty. Post-publication, the photographer kept reflecting on the context behind current conditions, looking into how the Conservative Coalition government undid a decade of progress following Tony Blair’s 1999 promise to eradicate child poverty. That decade saw child poverty halved via employment initiatives, public service investment, and family financial support. But, in the fourteen years since the Conservative government came into power in 2010, subsequent underfunding pushed up to 1.5 million children back into poverty through welfare cuts and other initiatives.

Mackay extensively explores one initiative within The Magic Money Tree: the two-child cap, a punitive policy limiting benefits to a maximum of two children per family, which disproportionately affects those already experiencing poverty. To do this, she includes a transcript of her own explanation, followed by excerpts from the Work and Pensions Committee meeting at Westminster, detailing criticisms of the cap a year after it was introduced in 2017, with one politician saying, “This is the single most disgusting policy I have ever heard of.”

The pages before and after this transcript feature critical and hopeful reflections from children and adults (journalists, teachers), with images of children playing outdoors, smiling in the sun—a jarring yet humanizing juxtaposition between parliament’s interiors where decisions are made and the streets where they play out.

Between these elements of critique, context, and first-person accounts, Mackay pulls a sensitive line from cold policy to individual lives, articulating experiences of poverty during the cost of living crisis with emotional immediacy and political relevance. However, her work remains reflective rather than prescriptive—she is not pushing for a specific solution but providing comprehensive documentation that might lead to a collective awareness of the nation’s grim social and political situation.

In the days before the release of The Magic Money Tree with Blue Coat Press, I interviewed Mackay about her process of collaboration and nuanced storytelling as a lens to look at widespread poverty and the cost of living crisis in the UK today. What follows is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

TF: How long did it take to put The Magic Money Tree together in terms of imagery and research?

KM: The exhibition focuses on the cost of living crisis in the UK in 2023. I photographed all of 2023 for the exhibition and, when the exhibition first opened in March this year, I started working on the book.

The exhibition was collaborative, but I took the book back into my own hands. The book allowed me to make that subject matter broader and present a story about the environment created in the UK before the cost of living [crisis began]. But I did not want it just to be about the cost of living crisis—I wanted to consider how we were already vulnerable in the UK because of neoliberalist policies that go back to the late 70s and early 80s.

In the book, I also include work made at the end of 2022 when I was warming up with the subject matter and starting to take pictures. I also included pictures that I took towards the end of 2023, after finalizing the exhibition, when I made one more trip to South Shields at Christmas time. It gives the book a nice ending. We made the book quickly, however, because I wanted to get it out before the election. But that didn’t happen. Rishi [Sunak] had other ideas.

TF: Why did you focus so much on young people in this project?

KM: Because I was one of those kids. Growing up in that environment, I know the impact and still feel it in my body daily. I have personal experience with the long-lasting effects of social inequality.

Tony Blair said in 1999 that he was going to eradicate child poverty. Ten years later, they were a third of the way there. Then the Conservative Coalition government came in and within a month, all that work was undone. We’ve had 14 years of underfunding and policies that have pushed children back into poverty, like the two-child benefit cap.

The UK is the sixth richest economy, it is unacceptable to have children living in poverty. It is achievable in a rich country to not have any children living in poverty.

TF: Our social reaction to poverty is often misdirected toward the people affected but, in your work, you shift that disgust and horror toward political decision-makers. Can you tell me about why your book confronts political policy?

KM: When people talk about poverty, especially politicians, the story that they tell is that people experiencing poverty are lazy and haven’t got it together.

That’s not the reality. I see my role as going into the world to meet people and recording their individual experiences. My photographs are close and intimate, I care about their story. It is a dance. I want to be agile so I can be a human being listening to someone’s story and do that in a way that’s safe, caring, and empathetic. Then, I want to zoom out to the bigger picture and connect their experience by bringing in policy and research.

TF: You take time to build relationships and get to know the community. Does this lead to the subject’s voice and their desires being more present in the work?

KM: People are involved and active in the process from the start. For instance, I did sessions with young people in Bristol from a youth group. We started just talking and I passed around my microphone, asking questions. It was interesting because they were teenagers and did not want to answer my questions. But when they passed the mic and didn’t answer, they were using their agency. As I asked more questions, the ones that had hesitated could not help but answer. That was my starting point—allowing for their agency and non-participation.

TF: What happened as you grew that bond?

KM: We made these placards, like protest signs, about anything that they cared about. But it wasn’t me coming in and saying, “Let’s make placards about the cost of living crisis.” We went outside, and they photographed each other holding up the placards. They were so energetic and enthusiastic. We talked about using your voice. Likewise, when I worked with Leighanne, who’s in the book, I kept going to visit and photograph her. Her story came in bits of conversation over nine months. If I had gone in with a list of questions, Leighanne wouldn’t have told her story.

Collaboration works when you have one person’s interests overlapping with another person’s interests. It has to be genuine.

TF: How prepared were people to reflect on their experiences with you?

KM: We were all going through this cost of living crisis to varying degrees. It was all over the news. It was a way for me to talk about poverty in a general way with them.

I am from a working-class background and still say I am working class. But I am aware in some places I go to, I am not seen that way. In Tipton, some saw me as a middle-class media type; that was a barrier. It was easier creating my first book in Northeast Scotland, as I am from there people could relate to me with more ease. People accepted me and were open. In Tipton, they didn’t quite get me, so there were some barriers.

TF: Can you touch on your inspirations: artists or writers you looked to when conceiving your project?

KM: I went to the Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol a year and a half before I took any photographs. I found inspiring work done in the 70s and 80s, like a book called Varna Road by Janet Mendelsohn. She made this beautiful book about only one family, who she photographed normally and tenderly.

In the UK press today, I just could not see anyone making work about poverty. Charities are not showing the people who are struggling. They only photograph people helping the people who are struggling – but then will photograph and show photos of people in Africa who are experiencing poverty. They are not showing pictures of people in the UK. After seeing Mendelsohn’s work, I thought I could tackle this subject.

TF: As more people are affected by the cost of living crisis, how can work like this raise awareness of social inequalities and the impact of politics on our quality of life?

KM: I am a sponge as an artist, soaking up everything happening, digging deep, and doing research. I make it into something, flip it, and throw it back into the world. When you reach an audience, the work comes full circle. Often, that sparks debate and conversation.

Sometimes people ask me: is there a call to action with your work? I don’t do that. It is just about communicating. I am bringing information and putting it in one place. Hopefully, for some people, it will educate them. Whoever sees it, it is up to them.

But, saying that, I think this is the last time I will make a photo book. I will do more writing along with my photography and move into a different space to reach my audience.

TF: When you say “audience”, who are you hoping your work reaches?

KM: The photobook audience is small and niche. It is for people who love photography and are not necessarily interested in what I am saying. I want to move into a wider space where my audience is people from working-class backgrounds and people who care about social issues. My audience is not in this photography space.

Related Posts

Kirsty Mackay On Centering Agency and Empathy To Photograph the UK’s Cost of Living Crisis

Kirsty Mackay has been photographing since age sixteen and identifies as a photographic artist, educator, activist, and filmmaker. In 2016, she received an honorable mention for the UNICEF Photo of the Year Award, and her work is regularly discussed in major online media, with TIME Magazine calling her a female photojournalist “worthy of recognition” in 2017. She’s often exhibiting within the UK, while, further afield, her work has also been featured in India, Italy, and Germany. She’s been to Paris Photo this year while touring her latest exhibition.

Despite her international success, the artist is strongly connected to her Scottish roots, with her politically-edged work centered on British working-class voices. The Glasgow-born photographer grew up working-class in Partick, Scotland—once saying that seeing the disparity between a more affluent neighboring suburb helped her be class conscious from a young age. She pursued photography at Glasgow College, before relocating to New York and London as a photography assistant to several well-known practitioners. She gained an MA in documentary photography and, ever since, has centered injustice in her work, calling out current dogmatic policies while being informed by her past, cognisant of the impact and long-lasting effects of social inequality.

As such, photography is just one part of Mackay’s expansive, socially driven projects, which she develops over long periods with a personable, research-led process. Mackay spends extended time in communities for her projects to form relationships and collect stories. In The Magic Money Tree, her latest project released this October, she continues to turn to poverty and discrimination in the UK, exploring the cost of living crisis across South Bristol (where Mackay lives), Tipton in The Black Country (West Midlands), and South Shields in the North East. The project exists as both an exhibition touring the UK this year, about the cost of living crisis in 2023, and a photo book examining its larger context.

In creating The Magic Money Tree, she would visit homes and community centers many times, sometimes not asking questions or taking photos, to let people connect with her at their own pace. She was assured that letting them lead the relationship would cultivate trust and, perhaps, if they were open to it, eventuate in photos or interviews for the book—as such, her material centers the subjects’ agency so much that it’s a theme in itself.

For instance, she spent a month visiting a food bank; instead of photographing the people inside, she captured bus shelters and pavements inscribed with quotes from their experiences, which form part of the book. She also spent extensive time in the home of 38-year-old mum Leighanne, with the book featuring an image with a quote from Mackay saying, “She shows me a photo on her phone. It’s a picture of her hugging him. He is now adopted. “I had nothing, I gave him up for adoption. If I’d had support, I could have kept him.””

In the book’s final pages, Mackay returns to Leighanne’s at Christmastime as she celebrates at home with her two eldest children. As a result, the book and its accompanying exhibition are devoid of the superficiality or patronization that can often be present in the work with marginalized populations. The core theme is dignity: she captures communities in their complexities and seasons.

Collaborative and personal processes are key to her practice. Mackay could spend such a critically drawn-out time developing relationships because of an Arts Council grant–– a case for fairly funding artists, especially photographers dealing with people, so that they have space and time to create deep, meaningful, and ethical work.

But as she concentrates on people to explore the causes and outcomes of poverty, Mackey never blames individuals—political policy is always the antagonist. In her previous book, The Fish That Never Swam (2021), she gathered first-person accounts in Glasgow, Scotland, placing their photographs between a research paper by NHS Scotland and The Glasgow Centre for Population Health about health inequalities as a direct cause of policy: the report found that, due to poverty and inequality, Glaswegians experience 15% reduction in life expectancy compared to other regions in the United Kingdom.

Similarly, in The Magic Money Tree, Mackay intersperses her photography with texts in the form of transcripts and quotes that speak to discriminatory political decision-making driving the cost of living crisis. Driven by high household energy bills, inflating food prices, and stagnant wages, the crisis has exacerbated the precarity and strain low-income communities already face.

In the UK, this has led to a 61% increase in the most extreme form of poverty between 2019 and 2022, with one in five people living in poverty and 4.2 million children affected. In 2024, these statistics are likely to be more dire. As one of her interviewees in the book said, “This is not a low-income issue”; a significant portion of the population is at risk, and political leaders are accountable.

As much as the book is empathetic to the people it represents, Mackay is serious about the urgent role of politics, outlining how decades-in-the-making conditions have made Brits vulnerable to widespread poverty. Post-publication, the photographer kept reflecting on the context behind current conditions, looking into how the Conservative Coalition government undid a decade of progress following Tony Blair’s 1999 promise to eradicate child poverty. That decade saw child poverty halved via employment initiatives, public service investment, and family financial support. But, in the fourteen years since the Conservative government came into power in 2010, subsequent underfunding pushed up to 1.5 million children back into poverty through welfare cuts and other initiatives.

Mackay extensively explores one initiative within The Magic Money Tree: the two-child cap, a punitive policy limiting benefits to a maximum of two children per family, which disproportionately affects those already experiencing poverty. To do this, she includes a transcript of her own explanation, followed by excerpts from the Work and Pensions Committee meeting at Westminster, detailing criticisms of the cap a year after it was introduced in 2017, with one politician saying, “This is the single most disgusting policy I have ever heard of.”

The pages before and after this transcript feature critical and hopeful reflections from children and adults (journalists, teachers), with images of children playing outdoors, smiling in the sun—a jarring yet humanizing juxtaposition between parliament’s interiors where decisions are made and the streets where they play out.

Between these elements of critique, context, and first-person accounts, Mackay pulls a sensitive line from cold policy to individual lives, articulating experiences of poverty during the cost of living crisis with emotional immediacy and political relevance. However, her work remains reflective rather than prescriptive—she is not pushing for a specific solution but providing comprehensive documentation that might lead to a collective awareness of the nation’s grim social and political situation.

In the days before the release of The Magic Money Tree with Blue Coat Press, I interviewed Mackay about her process of collaboration and nuanced storytelling as a lens to look at widespread poverty and the cost of living crisis in the UK today. What follows is an edited excerpt from our conversation.

TF: How long did it take to put The Magic Money Tree together in terms of imagery and research?

KM: The exhibition focuses on the cost of living crisis in the UK in 2023. I photographed all of 2023 for the exhibition and, when the exhibition first opened in March this year, I started working on the book.

The exhibition was collaborative, but I took the book back into my own hands. The book allowed me to make that subject matter broader and present a story about the environment created in the UK before the cost of living [crisis began]. But I did not want it just to be about the cost of living crisis—I wanted to consider how we were already vulnerable in the UK because of neoliberalist policies that go back to the late 70s and early 80s.

In the book, I also include work made at the end of 2022 when I was warming up with the subject matter and starting to take pictures. I also included pictures that I took towards the end of 2023, after finalizing the exhibition, when I made one more trip to South Shields at Christmas time. It gives the book a nice ending. We made the book quickly, however, because I wanted to get it out before the election. But that didn’t happen. Rishi [Sunak] had other ideas.

TF: Why did you focus so much on young people in this project?

KM: Because I was one of those kids. Growing up in that environment, I know the impact and still feel it in my body daily. I have personal experience with the long-lasting effects of social inequality.

Tony Blair said in 1999 that he was going to eradicate child poverty. Ten years later, they were a third of the way there. Then the Conservative Coalition government came in and within a month, all that work was undone. We’ve had 14 years of underfunding and policies that have pushed children back into poverty, like the two-child benefit cap.

The UK is the sixth richest economy, it is unacceptable to have children living in poverty. It is achievable in a rich country to not have any children living in poverty.

TF: Our social reaction to poverty is often misdirected toward the people affected but, in your work, you shift that disgust and horror toward political decision-makers. Can you tell me about why your book confronts political policy?

KM: When people talk about poverty, especially politicians, the story that they tell is that people experiencing poverty are lazy and haven’t got it together.

That’s not the reality. I see my role as going into the world to meet people and recording their individual experiences. My photographs are close and intimate, I care about their story. It is a dance. I want to be agile so I can be a human being listening to someone’s story and do that in a way that’s safe, caring, and empathetic. Then, I want to zoom out to the bigger picture and connect their experience by bringing in policy and research.

TF: You take time to build relationships and get to know the community. Does this lead to the subject’s voice and their desires being more present in the work?

KM: People are involved and active in the process from the start. For instance, I did sessions with young people in Bristol from a youth group. We started just talking and I passed around my microphone, asking questions. It was interesting because they were teenagers and did not want to answer my questions. But when they passed the mic and didn’t answer, they were using their agency. As I asked more questions, the ones that had hesitated could not help but answer. That was my starting point—allowing for their agency and non-participation.

TF: What happened as you grew that bond?

KM: We made these placards, like protest signs, about anything that they cared about. But it wasn’t me coming in and saying, “Let’s make placards about the cost of living crisis.” We went outside, and they photographed each other holding up the placards. They were so energetic and enthusiastic. We talked about using your voice. Likewise, when I worked with Leighanne, who’s in the book, I kept going to visit and photograph her. Her story came in bits of conversation over nine months. If I had gone in with a list of questions, Leighanne wouldn’t have told her story.

Collaboration works when you have one person’s interests overlapping with another person’s interests. It has to be genuine.

TF: How prepared were people to reflect on their experiences with you?

KM: We were all going through this cost of living crisis to varying degrees. It was all over the news. It was a way for me to talk about poverty in a general way with them.

I am from a working-class background and still say I am working class. But I am aware in some places I go to, I am not seen that way. In Tipton, some saw me as a middle-class media type; that was a barrier. It was easier creating my first book in Northeast Scotland, as I am from there people could relate to me with more ease. People accepted me and were open. In Tipton, they didn’t quite get me, so there were some barriers.

TF: Can you touch on your inspirations: artists or writers you looked to when conceiving your project?

KM: I went to the Martin Parr Foundation in Bristol a year and a half before I took any photographs. I found inspiring work done in the 70s and 80s, like a book called Varna Road by Janet Mendelsohn. She made this beautiful book about only one family, who she photographed normally and tenderly.

In the UK press today, I just could not see anyone making work about poverty. Charities are not showing the people who are struggling. They only photograph people helping the people who are struggling – but then will photograph and show photos of people in Africa who are experiencing poverty. They are not showing pictures of people in the UK. After seeing Mendelsohn’s work, I thought I could tackle this subject.

TF: As more people are affected by the cost of living crisis, how can work like this raise awareness of social inequalities and the impact of politics on our quality of life?

KM: I am a sponge as an artist, soaking up everything happening, digging deep, and doing research. I make it into something, flip it, and throw it back into the world. When you reach an audience, the work comes full circle. Often, that sparks debate and conversation.

Sometimes people ask me: is there a call to action with your work? I don’t do that. It is just about communicating. I am bringing information and putting it in one place. Hopefully, for some people, it will educate them. Whoever sees it, it is up to them.

But, saying that, I think this is the last time I will make a photo book. I will do more writing along with my photography and move into a different space to reach my audience.

TF: When you say “audience”, who are you hoping your work reaches?

KM: The photobook audience is small and niche. It is for people who love photography and are not necessarily interested in what I am saying. I want to move into a wider space where my audience is people from working-class backgrounds and people who care about social issues. My audience is not in this photography space.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.