How Khurshidan Bibi survived after her husband’s lynching, but struggles to live

In a small Rajasthan village, Khurshidan Bibi’s life revolves around a lone buffalo and daily walks to the forest. The forest is near her home, in Ghatmeeka village, where she takes her only buffalo for grazing. She returns home just before sunset and rests on a cot in a small courtyard. Then she goes to check on her small patch of wheat while her daughter-in-law prepares chapatis for dinner. On her way back, she sometimes chats with the women she passes. Now in her 40s, Khurshidan hardly recalls the time when she followed a different daily routine, when she lived a life that entailed more than observing the passing of time. In 2017, her husband Umar Khan was killed by cow vigilantes in Alwar. Seven years after his disappearance from her life, Khurshidan Bibi appears stuck in that moment, still navigating between loss and survival.

“Umar used to look after the cattle, I did not bother much with it, I took care of the kids at home,” Khurshidan said. The couple had eight kids together. When Umar was alive, they had two buffaloes and one cow. Most of the milk was used at home and the rest was sold to the dairy nearby. In 2014, they finally fulfilled their dream of building their own house. Khurshidan noted that despite financial struggles, Umar saved whatever little he could to build the house, bit by bit over a year.

That year, while giving birth to her seventh child, Khurshidan faced a difficult delivery and lost a lot of blood. Her recovery was long and slow, and she never quite regained her health. To have another person to help around the house with an ailing Khurshidan, the couple decided to marry off their eldest son, Maksud. He married the next year, and their new daughter-in-law moved into the house with them. Two years later, in 2017, Umar and Khurshidan were expecting another child. So that November, to sustain their growing family, Umar went to buy another cow from Alwar, the town closest to Ghatmeeka.

Three days after he left, Umar had neither returned from the Alwar cattle market, nor called or left a message. He used to call Khurshidan everyday when he was away, so Khurshidan grew concerned and restless. When she heard rumours of a body, shot and killed by a group of cow vigilantes in Alwar, she asked her younger brother to go and enquire about her husband’s whereabouts. He returned with the news that she most feared: Umar had been killed by a group of gau rakshaks—cow-protection vigilantes. He was on his way back from Alwar to Bharatpur, the district where Ghatmeeka village is located. His body was found near railway tracks in the Ramgarh area of Alwar.

Even though she anticipated something bad had happened to Umar, she never imagined him being violently murdered. “Umar was recognised by the swapi”—a traditional Mewati scarf—“he was wearing,” Khurshidan said. “His face was completely brutalised.” Umar usually had a smile on his face, she added. “Death happens to everybody,” she said, but it is the manner in which he was killed that still haunts her.

“He was shot three times,” she said, pointing to her stomach and chest to indicate where her husband was shot. “He was a pious man, he died on a Friday—the day of jummah,” Khurshidan recollected. Umar was laid to rest the next Friday, the day of congregational prayers, and “another auspicious day,” she noted. On the very day he was buried, she gave birth to their youngest son, Ibran.

“He used to do namaz five times a day, never missed a jummah, never harmed anybody, then why?” she asked, knowing there is no right answer to her question. “Nobody should be fated to such a death.”

A house of shared pain

When Umar died, despite being in the last month of pregnancy, Khurshidan did not go to her maayka—her parent’s house—as per the custom. “Umar did not like me going to my mother’s house,” she said, explaining her reason behind staying back. “Whenever I used to go to my maayka, Umar used to call my parents and ask them to send me back because he missed me; so I mostly stayed in Ghatmeeka.”

The house has three rooms, with the kitchen situated outside. Two of the rooms are occupied by the eldest sons and their families. Khurshidan sleeps in the courtyard on the cot during summers, and in winters, she sleeps in the third room with her younger children. The rooms do not have conventional decoration. Her eldest daughter, Myna, made flowers and other decorations from coloured papers and put them in Maksud’s room. Stacks of empty, plastic soft drink bottles were lined up along walls and on shelves; left from the wedding of her second-born son, Vikram, who got married in July 2022.

Vikram is married to Saima, the daughter of Rakbar Khan, who was also killed by cow vigilantes in 2018, in Alwar. Both fathers were unable to attend their children’s wedding. Under the same roof, Khurshidan and her daughter-in-law Saima share an unlikely connection of trauma inflicted by targeted hate crimes.

Even though Umar constructed the house for his family to build a future in it together, Khurshidan’s time in the house is often spent reminiscing about the past. She spoke of how she first met Umar on the day of their wedding; the marriage proposal had come through her aunt. She was only 15 years old and lived in a village near Ferozepur Jhirka; she had never been to a school or madrassa. She used to help her parents with their cattle, along with her three brothers and two sisters. Her father was also a dairy farmer, like most Mewati families.

Khurshidan came to Ghatmeeka after marrying Umar. “He was very malook,” she said, which means beautiful. “I used to get taunted by many family members and neighbours for how I looked compared to him. People always passed comments on it,” she said, adding, “but he never paid any heed to them, he loved me.”

“He was a good man, he never used to beat me,” Khurshidan said. This is an exception in the patriarchal environment of Mewat where domestic abuse is commonplace. “He would not even ask me to do anything if he saw I was sleeping.”

Even though seven years have passed, Khurshidan remains in poor mental and physical health. “I always feel scared, there is a restlessness,” she said. Maksud pointed out that she also often suffers from chest pain but visits to the local healthcare centre have not given them any diagnosis for the ailment.

Life after Umar

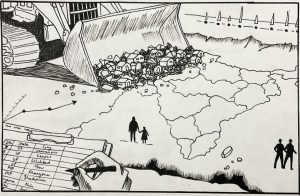

The financial state of the house worsened significantly since Umar’s death. They do not have cows anymore and stopped their dairy farming occupation. This phenomenon has been seen around Mewat, an area bordering Rajasthan and Haryana with a predominant Muslim population. Dairy farming had long been the most prevalent occupation in Mewat. However, the rise in cow vigilantism in the area affected the livelihood and safety of dairy farmers. Since the infamous murder of Pehlu Khan in April 2017, Muslim dairy farmers in Mewat live in the shadow of lynching. It was followed just months later with Umar’s lynching. As a result, Muslim dairy farming families in the region are scared to keep cows. There are constant raids, especially during functions where the police search for any trace of cow slaughter in the Mewati houses.

Khurshidan has a small patch of land, very close to her house, where she grows wheat, but all of that goes into sustaining the family. “We are a huge family, nothing is sufficient here. There is no option of selling anything outside.” Facing financial strain, Khurshidan wants to get another buffalo, so that she can sell the milk to the dairy or the neighbouring houses. But the cost of buying cattle is very high.

The widow’s pension of thousand rupees, and another two thousand from the Aman Biradari Trust, is barely enough for her to get by while contributing to the family. She is one of the very few women in Ghatmeeka who smokes, saying beedi is the only thing that can calm her down. “But now I don’t even have money to buy beedi,” she said.

Following his father’s death, Maksud suddenly had to become the breadwinner of the large 15-member household. He was just 15 years old when he was in Karnataka driving a goods truck and received the image of his father’s dead body for identification. But with Maksud assuming the role, it has reduced Khurshidan’s authority in the family. She is no longer the wife of the head of the family, or the mother who took care of the day-to-day chores. She is a widow under the protection of her eldest son. “Umar always listened to me; whatever he earned, he used to bring it to me,” Khurshidan said, reflecting on her current life. “Now, I do not have a say in anything.”

She does not engage much in the household chores either, as the two daughters-in-law have taken over those duties. She does not buy any new clothes and continues to wear worn out clothes. All these unforeseen changes have made Khurshidan recede into herself and become solitary in her own household.

The legal matters of Umar’s case are also handled by Maksud alone, Khurshidan is not involved in it. All six accused in the murder case are out on bail. After being delayed for years, the trial finally began at the district court in Laxmangarh, around 60 kilometres from Ghatmeeka, in February this year. The family has hired a lawyer and has also been trying to shift the case to the Alwar district court, which is closer to Ghatmeeka. Khurshidan did not know why the trial was proceeding so slowly, how the accused were granted bail, or why it was being conducted in Laxmangarh. “Maksud takes care of all that,” she said, in a tone of desolation

“Nobody cares about the case now,” Khurshidan said. “There was an uproar about it for a year, then it died out.” Meanwhile, a case of cow smuggling filed against Umar, filed by the Alwar police after his death, is also being heard before the same court. Khurshidan dismissed the accusation against her husband, saying that the cow was purchased for household purposes.

After so many years since Umar’s death, Khurshidan holds no hope for justice. Her disillusionment is rooted in the lack of support from the state government and politicians. In February 2023, Nasir and Junaid, two Muslim residents of Ghatmeeka, were burnt to death in a car, and cow vigilantes from the Bajrang Dal were accused of the crime. When political representatives came to the houses of the two victims, who lived near Khurshidan, they also visited her house. Khurshidan asked them for support in getting justice for Umar. But nobody did anything to help with her husband’s case, she said.

“I only want my younger children to study,” Khurshidan told me. “That is the only thing that can save us from this situation.” But this is a challenge of its own. Ghatmeeka, a rural area, lacks quality education options. The nearest government school lacks proper amenities. Abuzar, the second youngest sibling, attends this school. Sarfaraz, who is older to Abuzar, was dismissed from a madrasa in Aligarh after a dispute with other students. The madrasa authorities asked Khurshidan, the mother, to take him away, saying “Mewat’s children won’t be taught here.”

Khurshidan’s youngest daughter, Razia, studies at a Madrassa in Alwar and comes home twice a year for Eid. “I miss her and she also calls me and asks to visit her, but I cannot afford to go to Alwar,” Khurshidan said. Myna, the eldest daughter, is now 13, which is considered a nearly marriageable age for girls in Mewat, despite the legal prohibition on child marriage. However, huge dowry demands are putting added strain on the family. Myna was also in a madrassa in Mewat before she returned home because of Umar’s death, and was unable to return to her education because she was needed at home, since Khurshidan had just given birth to Ibran. When asked about sending Myna back to the madrasa, she replied that Myna was now old enough to be married.

Khurshidan added that the madrasas in Alwar, where her daughter Razia studies, teach Urdu but not Hindi or English. She thinks this is insufficient, and that the madrasas in Delhi would be a better option as they teach both Hindi and English. She wants to send her younger kids there.

All three of her eldest sons dropped out of school and now work as truck drivers. The third son, Taalim, is not even old enough to drive legally, but has procured a fake licence from middlemen in Assam, which is a common practice in the area. Khurshidan expressed concerns about the fact that truck driving is the only job available for her sons in Mewat. “I do not want any more of my children to be truck drivers,” she said. “I have three more boys. They need to go to school. They cannot be truck drivers.”

Khurshidan’s greatest worry is about Ibran, her youngest. The boy, who never got to meet his father, always accompanies his mother wherever she goes. She has not gone to her own mother’s home in Ferozepur Jhirka in over a year because she could not leave Ibran for several days at a stretch. “He is very small. I don’t know who will take care of him after me.”

Nowadays, Khurshidan lives a secluded life, in between her home and daily stroll in the forest with the buffalo. She occasionally visits her neighbours and chats with the women in the nearby houses. Ibran follows her everywhere and keeps her company, except when he is playing with Muhammed, Maksud’s eldest son.

“People thought I would not survive without Umar,” she said. “I survived, but I am not living. I have my sons and my family, yet I feel all alone.” After a pause, she added, “There is no life after Umar.”

Related Posts

In a small Rajasthan village, Khurshidan Bibi’s life revolves around a lone buffalo and daily walks to the forest. The forest is near her home, in Ghatmeeka village, where she takes her only buffalo for grazing. She returns home just before sunset and rests on a cot in a small courtyard. Then she goes to check on her small patch of wheat while her daughter-in-law prepares chapatis for dinner. On her way back, she sometimes chats with the women she passes. Now in her 40s, Khurshidan hardly recalls the time when she followed a different daily routine, when she lived a life that entailed more than observing the passing of time. In 2017, her husband Umar Khan was killed by cow vigilantes in Alwar. Seven years after his disappearance from her life, Khurshidan Bibi appears stuck in that moment, still navigating between loss and survival.

“Umar used to look after the cattle, I did not bother much with it, I took care of the kids at home,” Khurshidan said. The couple had eight kids together. When Umar was alive, they had two buffaloes and one cow. Most of the milk was used at home and the rest was sold to the dairy nearby. In 2014, they finally fulfilled their dream of building their own house. Khurshidan noted that despite financial struggles, Umar saved whatever little he could to build the house, bit by bit over a year.

That year, while giving birth to her seventh child, Khurshidan faced a difficult delivery and lost a lot of blood. Her recovery was long and slow, and she never quite regained her health. To have another person to help around the house with an ailing Khurshidan, the couple decided to marry off their eldest son, Maksud. He married the next year, and their new daughter-in-law moved into the house with them. Two years later, in 2017, Umar and Khurshidan were expecting another child. So that November, to sustain their growing family, Umar went to buy another cow from Alwar, the town closest to Ghatmeeka.

Three days after he left, Umar had neither returned from the Alwar cattle market, nor called or left a message. He used to call Khurshidan everyday when he was away, so Khurshidan grew concerned and restless. When she heard rumours of a body, shot and killed by a group of cow vigilantes in Alwar, she asked her younger brother to go and enquire about her husband’s whereabouts. He returned with the news that she most feared: Umar had been killed by a group of gau rakshaks—cow-protection vigilantes. He was on his way back from Alwar to Bharatpur, the district where Ghatmeeka village is located. His body was found near railway tracks in the Ramgarh area of Alwar.

Even though she anticipated something bad had happened to Umar, she never imagined him being violently murdered. “Umar was recognised by the swapi”—a traditional Mewati scarf—“he was wearing,” Khurshidan said. “His face was completely brutalised.” Umar usually had a smile on his face, she added. “Death happens to everybody,” she said, but it is the manner in which he was killed that still haunts her.

“He was shot three times,” she said, pointing to her stomach and chest to indicate where her husband was shot. “He was a pious man, he died on a Friday—the day of jummah,” Khurshidan recollected. Umar was laid to rest the next Friday, the day of congregational prayers, and “another auspicious day,” she noted. On the very day he was buried, she gave birth to their youngest son, Ibran.

“He used to do namaz five times a day, never missed a jummah, never harmed anybody, then why?” she asked, knowing there is no right answer to her question. “Nobody should be fated to such a death.”

A house of shared pain

When Umar died, despite being in the last month of pregnancy, Khurshidan did not go to her maayka—her parent’s house—as per the custom. “Umar did not like me going to my mother’s house,” she said, explaining her reason behind staying back. “Whenever I used to go to my maayka, Umar used to call my parents and ask them to send me back because he missed me; so I mostly stayed in Ghatmeeka.”

The house has three rooms, with the kitchen situated outside. Two of the rooms are occupied by the eldest sons and their families. Khurshidan sleeps in the courtyard on the cot during summers, and in winters, she sleeps in the third room with her younger children. The rooms do not have conventional decoration. Her eldest daughter, Myna, made flowers and other decorations from coloured papers and put them in Maksud’s room. Stacks of empty, plastic soft drink bottles were lined up along walls and on shelves; left from the wedding of her second-born son, Vikram, who got married in July 2022.

Vikram is married to Saima, the daughter of Rakbar Khan, who was also killed by cow vigilantes in 2018, in Alwar. Both fathers were unable to attend their children’s wedding. Under the same roof, Khurshidan and her daughter-in-law Saima share an unlikely connection of trauma inflicted by targeted hate crimes.

Even though Umar constructed the house for his family to build a future in it together, Khurshidan’s time in the house is often spent reminiscing about the past. She spoke of how she first met Umar on the day of their wedding; the marriage proposal had come through her aunt. She was only 15 years old and lived in a village near Ferozepur Jhirka; she had never been to a school or madrassa. She used to help her parents with their cattle, along with her three brothers and two sisters. Her father was also a dairy farmer, like most Mewati families.

Khurshidan came to Ghatmeeka after marrying Umar. “He was very malook,” she said, which means beautiful. “I used to get taunted by many family members and neighbours for how I looked compared to him. People always passed comments on it,” she said, adding, “but he never paid any heed to them, he loved me.”

“He was a good man, he never used to beat me,” Khurshidan said. This is an exception in the patriarchal environment of Mewat where domestic abuse is commonplace. “He would not even ask me to do anything if he saw I was sleeping.”

Even though seven years have passed, Khurshidan remains in poor mental and physical health. “I always feel scared, there is a restlessness,” she said. Maksud pointed out that she also often suffers from chest pain but visits to the local healthcare centre have not given them any diagnosis for the ailment.

Life after Umar

The financial state of the house worsened significantly since Umar’s death. They do not have cows anymore and stopped their dairy farming occupation. This phenomenon has been seen around Mewat, an area bordering Rajasthan and Haryana with a predominant Muslim population. Dairy farming had long been the most prevalent occupation in Mewat. However, the rise in cow vigilantism in the area affected the livelihood and safety of dairy farmers. Since the infamous murder of Pehlu Khan in April 2017, Muslim dairy farmers in Mewat live in the shadow of lynching. It was followed just months later with Umar’s lynching. As a result, Muslim dairy farming families in the region are scared to keep cows. There are constant raids, especially during functions where the police search for any trace of cow slaughter in the Mewati houses.

Khurshidan has a small patch of land, very close to her house, where she grows wheat, but all of that goes into sustaining the family. “We are a huge family, nothing is sufficient here. There is no option of selling anything outside.” Facing financial strain, Khurshidan wants to get another buffalo, so that she can sell the milk to the dairy or the neighbouring houses. But the cost of buying cattle is very high.

The widow’s pension of thousand rupees, and another two thousand from the Aman Biradari Trust, is barely enough for her to get by while contributing to the family. She is one of the very few women in Ghatmeeka who smokes, saying beedi is the only thing that can calm her down. “But now I don’t even have money to buy beedi,” she said.

Following his father’s death, Maksud suddenly had to become the breadwinner of the large 15-member household. He was just 15 years old when he was in Karnataka driving a goods truck and received the image of his father’s dead body for identification. But with Maksud assuming the role, it has reduced Khurshidan’s authority in the family. She is no longer the wife of the head of the family, or the mother who took care of the day-to-day chores. She is a widow under the protection of her eldest son. “Umar always listened to me; whatever he earned, he used to bring it to me,” Khurshidan said, reflecting on her current life. “Now, I do not have a say in anything.”

She does not engage much in the household chores either, as the two daughters-in-law have taken over those duties. She does not buy any new clothes and continues to wear worn out clothes. All these unforeseen changes have made Khurshidan recede into herself and become solitary in her own household.

The legal matters of Umar’s case are also handled by Maksud alone, Khurshidan is not involved in it. All six accused in the murder case are out on bail. After being delayed for years, the trial finally began at the district court in Laxmangarh, around 60 kilometres from Ghatmeeka, in February this year. The family has hired a lawyer and has also been trying to shift the case to the Alwar district court, which is closer to Ghatmeeka. Khurshidan did not know why the trial was proceeding so slowly, how the accused were granted bail, or why it was being conducted in Laxmangarh. “Maksud takes care of all that,” she said, in a tone of desolation

“Nobody cares about the case now,” Khurshidan said. “There was an uproar about it for a year, then it died out.” Meanwhile, a case of cow smuggling filed against Umar, filed by the Alwar police after his death, is also being heard before the same court. Khurshidan dismissed the accusation against her husband, saying that the cow was purchased for household purposes.

After so many years since Umar’s death, Khurshidan holds no hope for justice. Her disillusionment is rooted in the lack of support from the state government and politicians. In February 2023, Nasir and Junaid, two Muslim residents of Ghatmeeka, were burnt to death in a car, and cow vigilantes from the Bajrang Dal were accused of the crime. When political representatives came to the houses of the two victims, who lived near Khurshidan, they also visited her house. Khurshidan asked them for support in getting justice for Umar. But nobody did anything to help with her husband’s case, she said.

“I only want my younger children to study,” Khurshidan told me. “That is the only thing that can save us from this situation.” But this is a challenge of its own. Ghatmeeka, a rural area, lacks quality education options. The nearest government school lacks proper amenities. Abuzar, the second youngest sibling, attends this school. Sarfaraz, who is older to Abuzar, was dismissed from a madrasa in Aligarh after a dispute with other students. The madrasa authorities asked Khurshidan, the mother, to take him away, saying “Mewat’s children won’t be taught here.”

Khurshidan’s youngest daughter, Razia, studies at a Madrassa in Alwar and comes home twice a year for Eid. “I miss her and she also calls me and asks to visit her, but I cannot afford to go to Alwar,” Khurshidan said. Myna, the eldest daughter, is now 13, which is considered a nearly marriageable age for girls in Mewat, despite the legal prohibition on child marriage. However, huge dowry demands are putting added strain on the family. Myna was also in a madrassa in Mewat before she returned home because of Umar’s death, and was unable to return to her education because she was needed at home, since Khurshidan had just given birth to Ibran. When asked about sending Myna back to the madrasa, she replied that Myna was now old enough to be married.

Khurshidan added that the madrasas in Alwar, where her daughter Razia studies, teach Urdu but not Hindi or English. She thinks this is insufficient, and that the madrasas in Delhi would be a better option as they teach both Hindi and English. She wants to send her younger kids there.

All three of her eldest sons dropped out of school and now work as truck drivers. The third son, Taalim, is not even old enough to drive legally, but has procured a fake licence from middlemen in Assam, which is a common practice in the area. Khurshidan expressed concerns about the fact that truck driving is the only job available for her sons in Mewat. “I do not want any more of my children to be truck drivers,” she said. “I have three more boys. They need to go to school. They cannot be truck drivers.”

Khurshidan’s greatest worry is about Ibran, her youngest. The boy, who never got to meet his father, always accompanies his mother wherever she goes. She has not gone to her own mother’s home in Ferozepur Jhirka in over a year because she could not leave Ibran for several days at a stretch. “He is very small. I don’t know who will take care of him after me.”

Nowadays, Khurshidan lives a secluded life, in between her home and daily stroll in the forest with the buffalo. She occasionally visits her neighbours and chats with the women in the nearby houses. Ibran follows her everywhere and keeps her company, except when he is playing with Muhammed, Maksud’s eldest son.

“People thought I would not survive without Umar,” she said. “I survived, but I am not living. I have my sons and my family, yet I feel all alone.” After a pause, she added, “There is no life after Umar.”

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.

Related Posts

இடித்துத் தள்ளப்பட்ட ஷாமா பேகத்தின் வீடும் வாழ்க்கையும்