Torn Clothes, Scarred Bodies and Fenced Roads: Barbed wires as a material of occupation in Kashmir

When I was nine years old, I had one of my earliest encounters with the barbed wire—it was not my first, but it is the one I still vividly remember. I was on my school bus, nervously waiting for my stop. My father had collected my final-term results, so I knew anger and disappointment awaited me at home. When I saw the familiar maze of concertina coils on the road, I stood up. This was my stop, I lived on the right side of the all-wired road. I stepped down from the bus and watched it leave before walking to my home’s doorstep.

Within seconds of the door opening, I was greeted with a quick, harsh slap. Tears welled up in my eyes, as I dropped my bags and ran. My matamaal—maternal grandmother’s house—stood on the other side of the barbed wires on the road. I paused before the concertina wire, scared that it might rip through my blue tunic, or worse, cut through my flesh. Usually, my parents or my siblings would help me cross it. But that day, I had to cross it on my own. I walked along the coils until I found a less-tangled end of the wire and tried to squeeze past it. My white leggings got stuck in one of the wire’s blades near the left knee. My whole body was through except my left leg. I pulled at my leg until it was free, but my leggings tore in the process. I stared at the torn cloth for a few moments, and then turned and ran to my nani’s house.

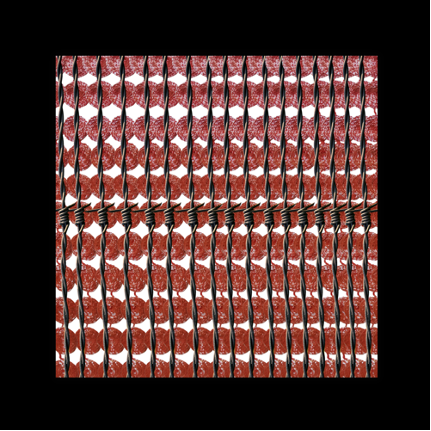

Barbed wires are an omnipresent object in Kashmiri lives. Every day, the average Kashmiri crosses paths with bunkers, convoys, police and army jeeps, barricades and barbed wires. These are the tools of occupation that we have seen and continue to see everywhere, and among these, barbed wires operate as a mass, imposing and violent means of stranglehold over Kashmir. They are rolled up into coils on road ends and pavements, policing access to buildings, schools, houses and parks, unspooled on roads, streets, and even hills.

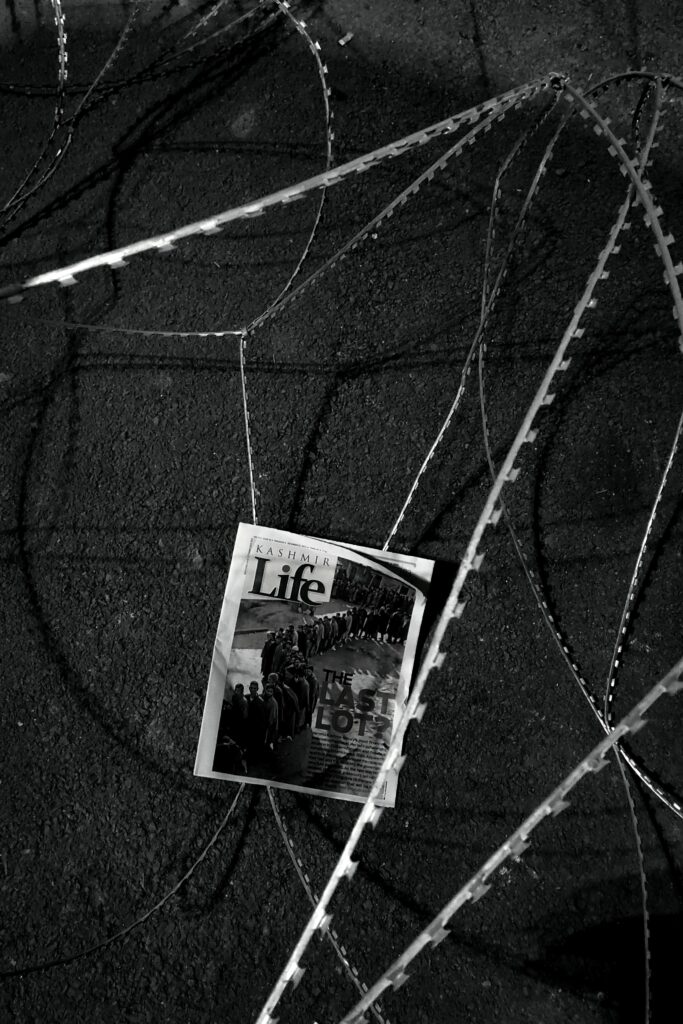

As a result, everyone in Kashmir has a story, a memory, or a perspective on barbed wires. For Khalid Bashir Gura, a Kashmiri journalist and researcher, the spooled barbed wire signifies a phase of “imposed normalcy,” and when unspooled, it means that the “mask of normalcy” is unveiled.

For a young Kashmiri doctor, barbed wires seem like “a cancer on Kashmir’s roads that keeps on growing, multiplying around people and animals, making them susceptible to physical injuries every day.” The doctor shared, “Recently, I was sitting on the bus and through the window, I saw a cow whose tail was stuck in these wires. It was writhing in pain, trying to free itself. That was a heartbreaking scene.”

The ubiquity of barbed wires points to the uncertain and conditional right of accessibility to spaces in Kashmir. These wires of stainless and galvanised steel, with different blade and loop profiles, are routinely injected into Kashmir’s landscape. When spooled, barbed wires send out a warning to Kashmiris, as if to say, “This road might be open today but if you misbehave, it will close tomorrow.” When unspooled, they spring into action and punish the misbehaving bodies by altering, deterring, curtailing, taming and endangering their movements.

Gura explained how the restrictions have become a routine part of his life as a journalist. “After the reading down of Article 370 and also during COVID, barbed wires were laid to close the roads,” he said. “Every other day, they used to change their position and alter our ways of movement, hindering our accessibility to information and resources. As a journalist, you had to show your press card, go through the scrutiny, and if they were satisfied, they moved these wires for you to go. But that is normal for us. That is a part, a given in the kind of work we do.”

Meanwhile, the doctor emphasised how the cruelty of the barbed wires was difficult to understand. “As a doctor, I try my best to help the injured but to see this wire that was designed to inflict harm, present everywhere in Kashmir, makes me feel helpless,” they said. “It’s as if they want injuries to happen here—daily, around the clock.”

The accounts of the doctor, the journalist, and the nine-year-old girl reflect how the experiences of barbed wires in Kashmir persist throughout our lives, right from early childhood. The barbed wire varies from being an incidental object in our stories, a daily obstacle in our livelihoods, and an inhuman imposition on our society. In art and literature, the weaponisation of the barbed wire by an occupying, colonial force has been well documented, and Kashmiris too have described its overbearing presence in their day-to-day lives. They represent this material of occupation in its varied forms, often using it to highlight their own materials of resistance.

As Kashmir goes to polls for the first time in a decade, it is important to reflect on the use of the barbed wire, and how Kashmiris engage with it. Amid all the rhetoric, narratives and promises of electoral campaigns, nobody speaks of the barbed wires, because everyone accepts the political reality of their entrenched presence in the Kashmiri landscape. Yet, as one photographer and resident of Srinagar insisted, “Barbed wires are not and will never be successful in Kashmir.” She added, “I look at the old buildings, gripped by these wires in Srinagar, and witness how, despite the long and painful times of being coiled, they still stand tall, resist and refuse to crumble down.”

*

ON 24 NOVEMBER 1874, A FARMER from the US state of Illinois by the name of Joseph Glidden received the patent for what would quickly become the most widely used and celebrated barbed wire. The technological innovation, consisting simply of two iron wires with a series of barbs, had taken the United States by storm, with farmers across the country looking to fence their land and livestock, and keep out wild animals. It had been 14 years since the first barbed wire patent, by Léonce Eugène Grassins-Baledans in France, which triggered a series of other patents across both countries, including four in just 1967.

Curiously, while Grassins-Baledans’ barbs were to be placed atop fences to keep trespassers out, effectively for similar security purposes as they are used today, the Glidden wire that became the most visible barbed wire at the time, was used for fencing and livestock. But it did not take long for it to transform from being a tool for agriculture to one used for colonial and military purposes. By the late 1800s, settlers in the United States were using barbed wires to force Native Indians out of their lands. Around the same time, the British also began deploying it widely against the Boers during their colonial war in southern Africa, to protect railway lines and keep out the cavalry, and also as a vast net to capture soldiers, marking its first use as an offensive weapon. Its use in wartime gained further popularity during the First World War when they were used as trench shelters.

During the Boer War, the British army also set up “laagers,” which were spaces cordoned off by barbed-wire fencing to hold civilian populations and would go on to be identified as concentration camps. Inspired by the British laagers, the barbed wire would eventually become a central design feature of the Nazi concentration camps. It was the first part of the camp that the Nazis constructed, and they took it a step further by electrifying the barbed wires.

As an agricultural fence and as a concentration camp’s boundary, the barbed wire divided a space into the inside and the outside. On the farm, the inside was for those protected by the barbed wires—the livestock. The outside was for the wild and threatening animals—the beasts. Originally, this is how a barbed wire divided a land, in a binary of the cattle-space and the savage-space. In his study, Barbed Wire: A Political History, Oliver Razac notes how the Nazis justified the use of electrified barbed wires by dehumanising the prisoners. “The camps were sustained by animalizing the enemy,” he writes. Razac continues:

[The] barbed wire is a device which separates those who will live from those who will die. More precisely, it produces a distinction between those who are allowed to retain their humanity and those reduced to mere bodies. On the one side, the productive subjects are preserved and covered in the guise of democratic rights. They are a herd, but one with a human face. On the other side, the abandoned are deprived of rights—they resemble beasts more than humans. They are not the equivalent of a herd, though, which has economic value and belongs to the interior. Those banished to the exterior are lost in the unknown; for those of the interior, they are wild animals, negative and threatening.

But in Kashmir’s landscape, barbed wires are present and laid everywhere. So, the question is: who form the herd and who are the savages? In the cruel twist of irony, the military use of barbed wires reversed the binary of its agricultural use, with the beasts using the wires to herd in their prisoners, and switching the narrative to justify the fencing of human beings. Given the colonially charged dynamics of how barbed wires are used in Kashmir, they do alter, limit and curtail our movements, but it does not protect us from the beasts. In fact, it harms and hurts us.

In Kashmir, this binary gets disrupted because Kashmiri bodies are treated as both, the herd and the beasts. They are the bodies who are kept in, and also out. They are the ones, in Razac’s words, who are not “allowed to retain their humanity” and “reduced to mere bodies.” They are a working herd, for the state and the capital, but without a human face. They are wild, negative and threatening, but also caged, tamed and subdued. Sometimes, they are seen and treated as beasts, and other times as the herd, but never as humans. Instead, they are the bodies banished without rights—by and for the humans who place the barbed wires.

In The Devil’s Rope: A Cultural History of Barbed Wire, Alan Krell refers to the close association of barbed wires with “westward expansion and white settlement” and comments on how its “partnership with such endeavours should come as no great surprise, since the device, after all, is about control and possession.” He quotes from “what was in effect a manifesto of barbed wire,” published by one of its biggest manufacturers in the United States in 1880:

Every man [sic] who builds a fence, does so, primarily, for his own greater enjoyment in his own lands, and the sense of better security in their exclusive possession enables him to protect his own improvements. In no part of the world, where the people have risen above the condition of the wandering savage, does the benefit of fencing fail to be understood and appreciated so soon as the inhabitants begin improvement and cultivation of land, and the establishment of home life.

Much like Grassins-Baledans’ original patent reflected the security use that would become central to the barbed wire, the manifesto by the Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company speaks to its use today. The manifesto’s language reflects the colonial psychology of the minds behind the manufacturing, marketing and consumption of barbed wires. Krell tags the terms “exclusive possession,” “wandering savage,” and “improvement and cultivation of land” as the “familiar refrain of the coloniser.” Beginning with the term “every man,” this manifesto not only reveals its target audience but also lays bare the fundamental allyship of fencing ideologies with male pride, male territorialism, male expansionism and male pleasure. To “own lands” and gain “exclusive possession” for “own greater enjoyment” are explicit expressions of territorial control directed at the colonial-masculinist consumers.

It is worth comparing this manifesto from the 1800s to the present-day website of a Mumbai-based fencing company, A1 Fence, which lists the Indian Army, Border Security Forces, Indian Navy and Indian Air Force as its clientele. On its “About Us” page, A1 Fence lists six domains in which they are active and two of those are:

Demarcation Solutions: You can claim your land, keep trespassers at bay and make a good impression all at the same time using A-1’s demarcation solutions.

High-Security Fencing Solutions: Our high-security fencing solutions protect you from intrusion attempts so that you can work with a sense of security.

The language reflects the same objectives of ownership, territorial control, pride and security. Moreover, the “wandering savages” are now labelled as “trespassers” and “intruders,” yet the human subjects continue to be treated as mere bodies, indistinguishable from the herd and the beasts. Therefore, all bodies who don’t recognise, admire, respect and fear fencing, invite harm upon themselves. Every day, these bodies are to be punished, trained, and punished and trained, forced to see fencing as a reminder of who owns the land, who owns them, and behave accordingly.

Similarly, in Kashmir, barbed wires are a material way by which the colonial ‘humans’ symbolise their ownership over the land and its bodies. Even buildings are not spared, with old ones wrapped, almost enveloped, in barbed wires. Like some industrially produced pythons, with steel bodies, sharp blades and aggregating potential, concertina wires coil around the walls of buildings in a chilling, predatory way. Due to their absurdly wired exterior, my sister once expressed that some of these buildings are “unrecognisable” to her. Barbed wires, as a material of occupation, have made places not only inaccessible but also unrecognisable, in Kashmir, to a Kashmiri.

*

BARBED WIRES FEATURE PROMINENTLY in the art of and about Kashmir. In Malik Sajad’s graphic novel, Munnu: A Boy From Kashmir, barbed wires, for the most part, are drawn as plain loops, without their twisted barbs and sharp blades, barring some exceptions. In another graphic novel, Kashmir Pending, by Naseer Ahmed and Saurabh Singh, barbed wires are drawn on prison walls, border fences and training grounds. The cover image of Debasmita Dasgupta’s Terminal 3 is of a Kashmiri girl with red cheeks, wearing a hijab, and barbed wires in front of her portrait. Their presence in these works of art reflects the dominating role barbed wires play in Kashmir. As a material of occupation, strong on the symbolic front, barbed wires are imagined, seen, written, captured and drawn as a permanent, inseparable, and inevitable element of Kashmir’s militarised aesthetics.

While I was reading these graphic novels, whenever my gaze landed on the material of barbed wires, its inked loops grew sharp blades in my mind. I could visualise its detailed appearance without seeing the same on the paper. This visual reading experience reminded me of the first nineteen years of my life, before I had spent any significant time outside of Kashmir, when I would see, move over and navigate around the army wires everywhere.

But later, after I completed my bachelor’s outside Kashmir and returned home, I saw the barbed wires again—and for the first time, I looked at it and thought, “This shouldn’t be here.” It took me years to think and utter these words. The use of barbed wires in the occupation of Kashmir is marked not just by its inescapable deployment by Indian security forces, but equally in the vicious efforts to instil its violent anatomy into the daily Kashmiri psyche. This is the psychological cruelty of occupation, where the sighting of and an assault by the occupier’s materiality becomes—or rather, is made—normal.

Stressing on the symbolic dimensions of its application in Kashmir, Khalid observed how, for Kashmiris, barbed wires function as an occupier’s sign, a recurring symbol that repeatedly reminds us about their ownership over the land and its people. In simple words, ownership means a state of owning or possessing something. Therefore, one could argue that the colonial property of a barbed wire displays the frightening imagination of its owners who don’t treat, count or even see Kashmiris as humans.

While making this observation, it is important to take note of Deepti Misri’s words in her paper, “Showing Humanity: Violence and Visuality in Kashmir,” which studies visual media from the region in the wake of the Indian state’s violent crackdown against protests in 2016. “The dehumanization of Kashmiris by the Indian state and its votaries does not mean that Kashmiris themselves have ‘lost’ their humanity,” Misri wrote. “Indeed, Kashmiris frequently invoke humanity as a moral category to argue that it is Indians who have no humanity as they regularly register attempts to dehumanize them on the part of Indians.” Likewise, the barbed wires and their widespread deployment in Kashmir do not erase the humanity of Kashmiris, but reveal the dehumanising objective and desire of ownership behind their use.

In this dehumanisation, then, Kashmiri lives and bodies become dispensable, and as a result, the use of barbed wires, in turn, becomes acceptable. Materials of control and possession such as barbed wires are placed on “unreal” bodies, who are treated differently than real humans. In Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, Judith Butler discusses the infliction of violence on the unreal, and the exposure of and complicity in such violence. Butler highlights the “cultural contours of the human” and how our understanding of what is human sets “limits on the kinds of losses we can avow as losses.” They note:

If violence is done against those who are unreal, then, from the perspective of violence, it fails to injure or negate those lives since those lives are already negated. But they have a strange way of remaining animated and so must be negated again (and again). They cannot be mourned because they are already lost or, rather, never “were,” and they must be killed, since they seem to live on, stubbornly, in this state of deadness.

Hence, in the case of Kashmiris, the subject of their physical vulnerability to violence, realised or unrealised, is not mulled over, questioned and grieved. But if all of the Kashmiri bodies are not among the real humans, then how can anyone harm, hurt or kill the unreal? If their lives do not count as lives, then, how do you declare them dead? If a barb is stuck in Kashmiri flesh, can we not classify it as an injury in the language of humans?

Barbed wires are brought and laid to restrict, restrain and harm the negated Kashmiri bodies, again and again, because these bodies continue to move, to “remain animated.” Thus, through the processes of repeated negation, the Kashmiri body is kept suspended between life and death, living and dead, cattle and beasts, wild and caged, movement and restraint; till the realisation of the coloniser’s end goal—complete immobilisation.

*

IT HAPPENED IN 2014. I was 11 years old and one afternoon, my mother asked me to go and call my grandmother, who was working in our waer [kitchen garden]. I went to fetch her but after some time, as I was walking, a pack of dogs started chasing me. I panicked and ran. While running, I didn’t notice the barbed wires that were laid there and I fell—on the wires. They were not the concertina wires that we see today; instead, the old, twisted ones. One of the wire’s barbs hit below my right eye, got jammed and tore the flesh there. I was rushed to the hospital. Nobody was allowing me to see myself because they thought that I would be scared. But when I was being driven to the hospital, I saw myself in the car’s side-view mirror. Even today, I remember what I saw in that mirror—my face, my eyes, my blood and my torn flesh. Even today, whenever I look in the mirror, the scar below my right eye looks back at me and I am eleven again. But I don’t turn away or flinch; rather, I carry it as a part of me—my body, memory and life.

Aiman Fayaz Dar, a Kashmiri photojournalist, shared this story with me. As she spoke, I felt a lump forming at the back of my throat, slowly growing as she recounted her story, so different from mine and yet so uncomfortably familiar. Later, she shared a photograph. In it, the scar left by the barbed wire below her right eye creates an ineluctable site: where the materiality of occupation meets the corporeality of resistance.

Ten years ago, the colonial material of barbed wire scarred the flesh of a Kashmiri girl but now, that girl has grown up and is looking straight into the camera’s eye—to click and capture the same scar. In her analysis of identity card photographs of Algerian women clicked by Marc Garanger, a French army photographer, Karina Eileraas observes how such “provocative images” not only document the “violence of colonial representation but also the destabilising potential of Algerian women’s looks.” Similarly, Dar, as both the photographer and the photographed, not only documents the violence committed on her by the colonial materiality, but concurrently, with her look, destabilises the looming, invasive gazes of colonial-masculine eyeballs. She documents her scar herself and with a sharp, penetrating gaze asks, “What are you looking at?”

The privilege of “looking” is often considered to be the optic ammunition of the colonial, masculinist gazes, but what if the photographed, by looking at the camera at will, disrupts the dynamics of the same? In this photograph, Dar has seized the power of looking by capturing and documenting the visuals of her eye, of her scar. In doing so, she has also anchored her scarred body and memory against the occupation’s materiality to enact, register and assert her resistance against any possible erasure of it.

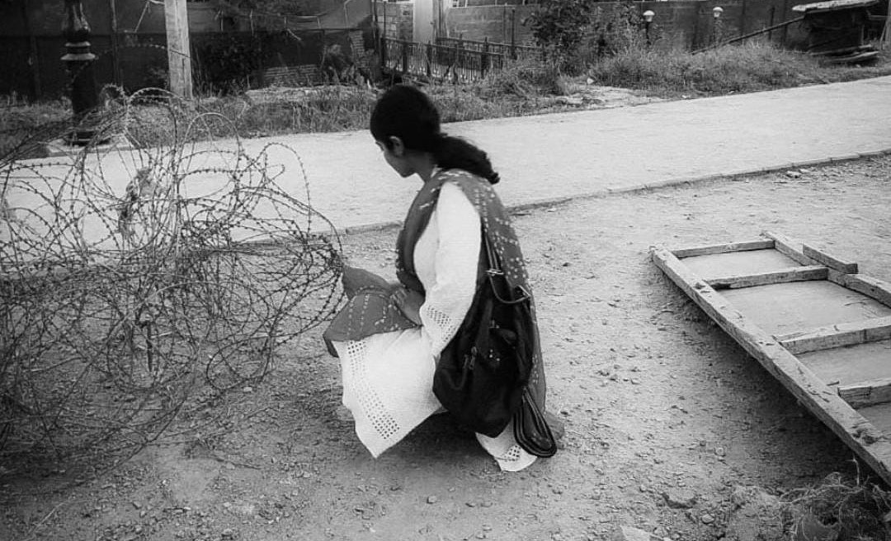

In another photograph, Dar’s friend captures a moment in which her dupatta is caught in the barbed wires. It’s a shared experience. A cloth stuck in and torn by a barbed wire is a common, everyday affair in Kashmir. Almost everywhere, Kashmiri bodies and their clothes are exposed and vulnerable to these wires. In this photo, Aiman’s body, her movements, her work, her time—all have been halted by this sudden entrapment. It prevents her from moving forward or back—stopping her in time, in that moment. And for it to begin again, she can either pull at her dupatta, which can cause more tearing or, she can slowly and carefully navigate it out of the barbed wires’ blades.

But this photograph is less about the past and the future, and more about the halted present; the present of a Kashmiri woman stuck in a barbed wire. A present that rarely gets captured because time is recorded differently in Kashmir. The untorn dupatta of the past becomes the torn dupatta of the future, and the cause and act of its tearing will be wiped out. However, this photograph records and freezes that present, that act of causation, where the materiality of occupation intrudes upon the corporeality of Kashmiris and in doing so, twists and halts its time geography as well.

Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name Bell Hooks, in her book, Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics, reflects on the South African Freedom Charter’s phrase, “Our struggle is also a struggle of memory against forgetting.” She constructs on it the idea of “politicisation of memory,” which “distinguishes nostalgia, that longing for something to be as once it was, a kind of useless act, from that remembering that serves to illuminate and transform the present.” Memories are political and the act of remembering them, and reproducing them as Dar has, is an act of resistance. And within spaces such as Kashmir, these acts of remembering are recalled, re-lived and re-shared to organise and mobilise ourselves—for and because of each other.

“Whenever I had to go for my tuition classes, barbed wires were a stark reminder of the restrictions that I was under,” a resident of Baramulla in her twenties recalled, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “They always made me feel unsafe.” She recounted one incident that had stuck with her. “On one occasion, I tried to move the wire to pass through but its sharp blades cut in deep,” she said. “I was also warned to never touch it again, for sometimes, it carried an electric current. Even the people that lay it use gloves to untangle and spread it. I always wondered how they bring and lay these wires.”

For a resident of Kulgam, who also requested anonymity, the experience of barbed wires was marked by a feeling of a “male colonial gaze” that “constantly imposes a state of nakedness on us.” In her “politicised memory,” barbed wires continue to heighten the climate of hyper-visibility and hyper-surveillance around her.

The varying associations in each memory around the barbed wire highlight the different facets of its occupation in the lands and minds of the Kashmiris. The Baramulla resident was struck by how the material that left her feeling unsafe in her own land posed no threat to the outsider. Meanwhile, the Kulgam resident perceived the material as the outsider’s constant surveillance over the locals. Their politicised memories, although distinct and personal to each of their separate experiences, remain bound together for their defiance of the barbed wires and what it represents in how they remember it.

*

IN REGIONS SUCH AS KASHMIR, where resistance is conceptualised and enacted against oppressive forces repeatedly over time, materials can be associated with two categories—materials of occupation and materials of resistance. In the Kashmiri imagination, the material of resistance need not be a mechanical device used against the occupying forces, but even an assertion of their culture, such as a pheran—a traditional robe-like garment—becomes a material of resistance. Meanwhile, not only barbed wires, but the bunkers, the army and police jeeps, their barricades, and their weapons—all are materials of occupation that confine, assault and attack the corporealities of resistance. Apart from their evident violent materiality, these devices also function as the coloniser’s symbols of their ownership and control; their policing and surveillance; and their pride and pleasure.

In October 2019, after the effective abrogation of Article 370, on the 68th day of the state-imposed shutdown, a Kashmiri man wore a barbed wire around his face as a form of protest in Srinagar. The image is a declaration of his resistance and one that is particularly powerful for using a material of occupation. It says, “See, this is what an occupied body looks like.” The proximity of barbed wires to the head, face and flesh of this Kashmiri man emphasises the suffocating, coercive and intrusive nature of the occupation and its materiality in Kashmir. The proximity further highlights the Kashmiri’s daily vulnerability to abuse, harm and violence. Moreover, in doing so, the vulnerability becomes a public act of protest—not antithetical to resistance, but a part of it.

Judith Butler, in Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance, states that “vulnerability is not exactly overcome by resistance, but becomes a potentially effective mobilizing force in political mobilizations.” They describe it as a “part of the very meaning of political resistance as an embodied enactment.” Likewise, by covering his head with barbed wires, this Kashmiri man not only bares his vulnerability to occupation and its materiality but it is through this act of baring that he enacts and registers his resistance.

“If we oppose vulnerability in the name of agency, does that imply that we prefer to see ourselves as those who are only acting, but not acted on?” Butler asks. “And how might we then describe those regions of both aesthetics and ethics that presume that our receptivity is bound up with our responsiveness, a zone in which we are acted on by the world, by what is said and shown, by what we hear, and by what touches us?” Materials of occupation act on the corporealities of resistance to hurt, harm and kill them. The individual and collective vulnerability of Kashmiri bodies to the materiality of occupation induces, advances and enhances their varied performances of resistance, mobilisation and agency against the oppressive forces.

Earlier this year, Maaje Zevwe—which is Kashmiri for ‘mother tongue’—a Kashmir-based feminist magazine where I am the editor-in-chief and a co-founder, released its annual issue, Yaarbal: Letters From Kashmir. In one image, titled Karsa Myon Nyaai Andhae—a popular verse from a poem by Mahmud Gaami, which is translated by Mufti Mudasir in his book, Yusuf’s Fragrance, as “When will you end my predicament?”—the photographer Syed Khateeba captures a silver ring hanging on one of the blades of a concertina wire. A ring usually “symbolises love, commitment and relational life,” but for women, it can also denote “societal expectations, identity crisis and burdens of such relationships,” Khateeba told me. “Both a ring and a barbed wire have a looped shape. A barbed wire signifies political restriction and control over one’s mobility and a women’s ring, on the other hand, personifies societal boundaries, confinement and policing.”

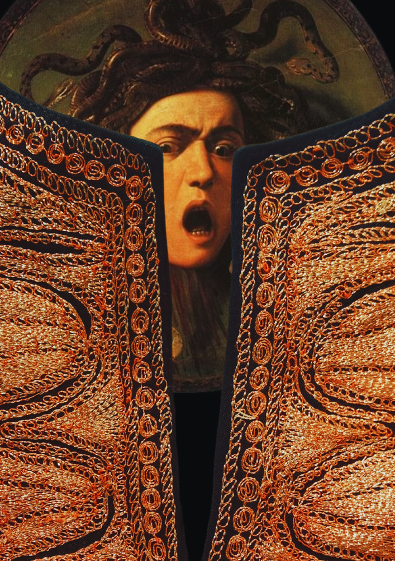

Khateeba shows how materials of resistance, as a category, are intimate and personal, but also mutual and collective. In my own art practice, too, resistance is reflected through the personal and the collective. In Zahida’s Anger, I placed my mother’s pheran naal—a collar—as a material of resistance, with Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Medusa, to create a scene of feminist rage, against the sexually-violent crimes committed on Kashmiri women’s bodies. In another piece, Deaar, which translates to Window, the tilli—embroidery work—of a Kashmiri woman’s frock is vertically set with twisted barbs. Replicating the layout of a window, the congested yet sequential appearance of this piece imitates the thorough, systematic persistence of barbed wires in Kashmiri lives. By placing the tilli as a material of resistance and barbed wires as a material of occupation, I created this deaar to look through, look at and witness a Kashmiri woman’s resistance against the barbed wire.

These works of art and protest demonstrate how the binary classification of materials of occupation and resistance is not set in stone. In fact, not only have the barricades been used as a material of resistance, but there are colonial attempts to erase, distort and seize the materiality of resistance as well. For instance, anti-state graffiti, as painted on the walls and shop shutters, is art, as a material of resistance. Over the years, the Indian state has removed the graffiti, distorted its painted words to change their real and intended meaning and even commissioned artists to draw murals of Kashmir’s culture, beauty and heritage in the occupied public spaces. In 2015, a mural project was sanctioned for Srinagar, and as the researchers Mudasir Amin and Iymon Majid found, “the locations for these commissioned artworks were primarily walls painted with ‘anti-India’ graffiti.”

But what happens when these state-commissioned murals, of the cultural and scenic genre, have uniformed men, with arms, prowling in front of them? Barbed wires laid around them? Bunkers erected before them? By and through their own materiality, colonisers are unmasked. Every material of occupation, around these murals, not only ultra-visibilises the violent—such as the armed men, bunkers, convoys and barbed wires—but also exposes the colonial make-up of the apparent non-violent: the state-commissioned art.

The materiality of both occupation and resistance, therefore, exist on a physical level, as tangible objects that are a part of our daily lives, and a symbolic one, reflecting the socio-political realities within which they exist. While the materiality of occupation carries a desire and a potential to curtail and harm the bodies of resistance, the materiality of resistance refuses to yield, and calls for freedom.