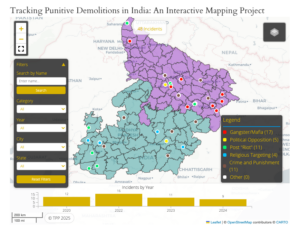

In recent years, as demolitions became a recurrent feature of India’s new extrajudicial justice system, many writers decried the bulldozer as an affront to the rule of law. But perhaps the bulldozer is a surprisingly apt metaphor to describe the rule of law in contemporary India. Its purpose is destructive and punitive, not preventive or rehabilitative; in theory, it should only be used as per established procedures, but in practice, it is a tool weaponised by those in power; it disproportionately oppresses minority communities; and it is vulnerable to crony capitalism. If anything, bulldozers in the public imagination have come to represent a more accurate representation of the rule of law in India than the ideal of rule of law itself.

One of the clearest indicators of this transformation is that words like “demolition,” “bulldozer justice,” and “bulldozer baba,” have become intrinsic to India’s legal and political vocabulary. The semantics of these words represent in themselves structures of bias and discrimination. Extrajudicial demolitions contravene several fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution of India, as well as multiple international housing-rights and human-rights principles. The political and institutional dynamics involved in extrajudicial demolitions make for a scary reality check about the current state of India, where the report card of the legal system is not scored based on the its adherence to the law, but in its enforcement of Hindutva. So it doesn’t matter if the BJP-RSS nexus has failed in complying with the legal standards of the Constitution or international human rights—it scored high where it matter: A+, the report card reads.

The punitive use of bulldozers to demolish a home or property of an individual, usually from the Muslim community, accused of being involved in a criminal activity or communal violence has created its own political and emotional economy. This economy is perpetuated and sustained at both institutional (state actors) and individual (non-state actors) levels, which flourish when such acts of injustices are carried out. The entire act, from exploiting and scapegoating a marginalised community to demolishing their property, becomes a political spectacle. It is justified and normalised to the extent that the entire state machinery, from district development authorities to the state government, comes together to justify an arbitrary decision of a state official. The punishment allows instant gratification and retribution, by dealing with a perceived threat without wasting time. The wider public accepts and celebrates this punishment as the news media continuously applauds the state actors for taking stern action against “rioters” or “criminals.”

On papers and in courts, the state justifies the act by claiming illegality of the property, but on the ground, it cultivates and encourages the public perception that it was in fact an act of punishment. As a result, it does not matter that the state regularly conducts extrajudicial demolitions that do not comply with legal procedure—to the contrary, the aggressive, assertive state that is not concerned by the hassle of due process only strengthens its public appeal. This collective punishment has become yet another manifestation of the deliberate and systemic marginalisation of the Muslims of India. The punitive act of demolition gives out a clear message of Hindu supremacy to their voters, reinforcing existing hierarchies and inequalities.

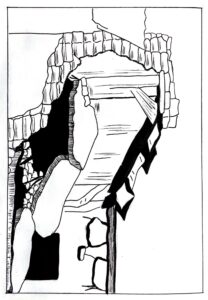

This state-manufactured displacement is not only punitive, it is also unlawful, routinely conducted without following due process. After the dust settles, the individual who was first criminalised and made to see bulldozers wrecking their property is left to deal with trauma, loss, and displacement along with their families. Once a property is demolished, its inhabitants must reconcile a punishment that their minds cannot justify. The only question they keep asking everyone—the officials, the media, the people around, and themselves—is, “Sab kuch ek taraf, lekin aap kisi ka ghar kaise gira sakte hain?” (Setting aside everything, how can you demolish someone’s home?)

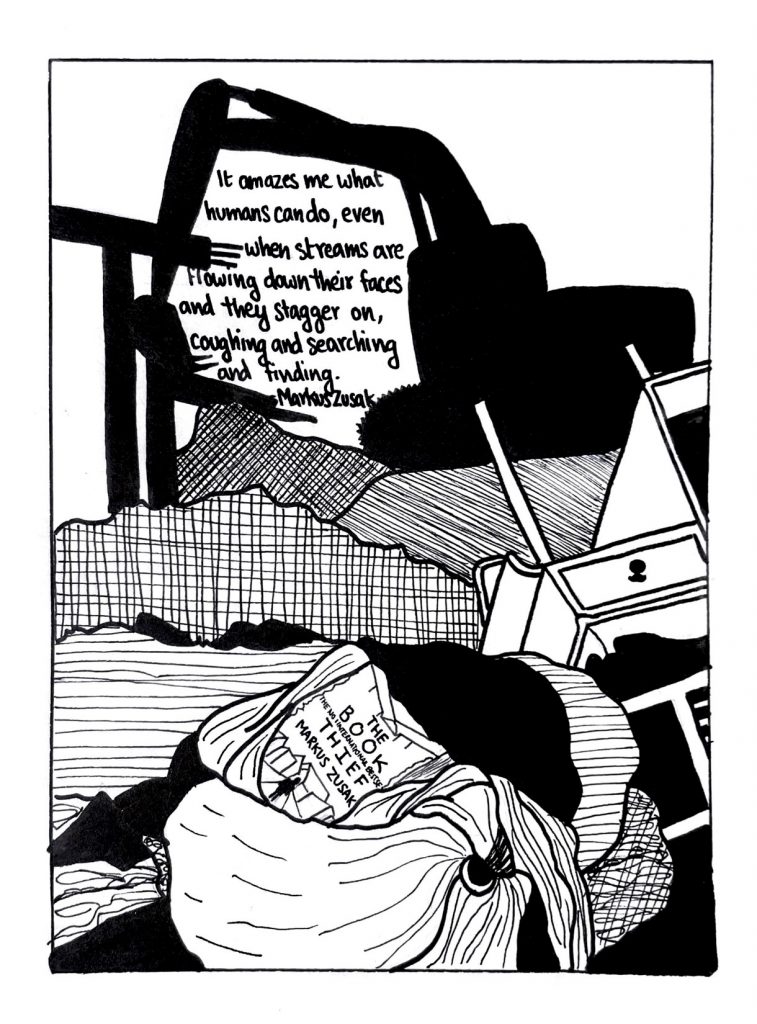

Who can punish and who can be punished? What is the meaning of this punishment? What is the message of this collective punishment? What does it mean to have your home demolished? The newsletters and research of the Demolitions project will attempt to answer these questions. It will chart the historical, legal, political dynamics that shape the practice of extrajudicial demolitions in India. In the process, we aim to identify and understand the demolitions—of procedures, places and peace—and give voice to the stories of those directly affected.