Defining extrajudicial demolitions: Understanding the legal framework and the impunity from it

In India, the term “extrajudicial” is normally associated with unlawful killings by the police in staged encounters, but in recent years, it has become exceedingly relevant for another state-sanctioned violation of human-rights and rule of law: bulldozer demolitions. Extrajudicial refer to actions taken in contravention of the due process of law and without judicial sanction. The crucial aspect of extrajudicial actions lies in the bypassing of established legal frameworks designed to ensure accountability and justice. While judicially sanctioned demolition drives can also be contested as violation of human rights, within The Demolitions Project, we will be focusing on extrajudicial demolitions, which tend to be inherently punitive in nature.

The Demolitions Project will explore the implications and illegalities of extrajudicial and punitive demolitions actions. It will focus on the disproportionately impact on marginalised populations, and the mechanisms by which the state continues to operate with impunity and complete disregard for due process. It is important to first understand the legal framework on demolitions in India to set out the parameters of this research project, and in doing so, demonstrate how the institutional safeguards within the law are subverted in the punitive, extrajudicial demolitions seen in the country today.

Legal framework governing demolitions

The Supreme Court in various pronouncements, numerous high court judgments, and India’s international commitments, have all long established the fundamental right to housing in the country. Yet, central and state governments continue to conduct forced evictions and extrajudicial demolitions under the garb of encroachment and illegal construction. There are several legal protections available for individuals facing extrajudicial eviction and demolition prescribed under state, national and international laws.

Though there is no pan-India law that governs demolitions, evictions or housing across all states, the legal framework is underpinned by constitutional guarantees and different statutory provisions designed to safeguard property rights and to ensure procedural fairness. For instance, Articles 14 confers the right to be treated equally before the law; Article 21 protects the right to life and personal liberty, which also mandates that any restriction on it must be as per a procedure established by law; Article 15 guarantees the right against discrimination; and Article 19 ensures the rights to move freely and to reside and settle in any part of the country. Moreover, Article 300A of the Indian constitution guarantees the right to property, and explicitly stipulates that no individual shall be deprived of their property except by the authority of law.

These constitutional safeguards mandate that any act of eviction or demolition must comply with established legal protocols, ensuring that affected parties are given an opportunity to be heard and to contest the state’s actions. These safeguards are adopted into the various laws and policies that regulate demolitions and evictions in India. They include the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act of 2006—commonly known as the Forest Rights Act; the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act of 2013; the Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993; the Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act of 1956; the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act of 2014; the National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy of 2007; Draft National Slum Policy of 2001; and the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana launched in 2015.

These laws and policies require that notices be served to property owners, hearings be conducted, rehabilitation or compensation be provided where applicable, and that individuals may appeal eviction or demolition orders. But today, extrajudicial demolitions bypass these procedural requirements, breaching legal norms and principles established by the rule of law.

The constitutional safeguards are also adopted into the state-level legislations governing demolitions. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, the Urban Planning and Development Act of 1973 guarantees that prior to any demolition, the development authority must first issue a notice to the concerned individual informing the grounds of the demolition; grant them an opportunity to be heard, which includes making a representation in writing; and ensure the right to appeal the demolition order before the District Judge. In fact, section 27 of the Act mandates that any person aggrieved by a demolition order can appeal it within 30 days.

Similarly, in Delhi, demolitions are governed by the Delhi Municipal Corporation Act, 1957, and the Delhi Development Authority Act, 1957. The Madhya Pradesh Municipal Corporation Act of 1956 and the Madhya Pradesh Nagar Palika Act of 1961 regulate the state’s evictions and demolitions. In Gujarat, demolitions are primarily governed under the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act, 1976; the Gujarat Municipal Corporation Act, 1949; and the Gujarat Panchayat Act 1993. All these state laws and policies require demolition of properties to be conducted with proper legal procedures. Additionally, the state must justify the necessity of any demolition with clear legal and administrative reasons, ensuring transparency and accountability in the process.

These legal provisions reflect the international legal consensus on the protection against arbitrary demolitions and evictions. Within the international human-rights framework, the right to adequate housing is affirmed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, which India has signed and ratified. The UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing has defined the human right to adequate housing as, “the right of every woman, man, youth, and child to gain and sustain a safe and secure home and community in which to live in peace and dignity.”

The United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has further elaborated on what constitutes “adequate housing,” and includes among seven core principles the legal protection against forced eviction, harassment and other threats. The committee further defined forced evictions as:

Permanent or temporary removal against the will of individuals, families or communities from their homes or land, which they occupy, without the provision of, and access to, appropriate forms of legal or other protection.

Thus, there is an explicit international obligation to ensure the right to adequate housing, which includes the protection against unlawful demolitions and forced evictions. In fact, the extrajudicial demolition of homes and businesses violate a range of internationally recognised rights apart from the right to adequate housing as well, such as the right to security; the right to freedom from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment; and the right to resettlement and adequate compensation for violations and losses.

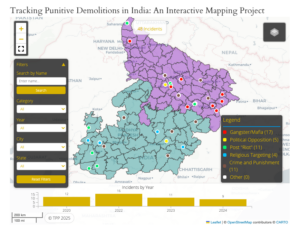

Documenting extrajudicial demolitions

For the purposes of The Demolition Project, we will look at demolitions that occur in violation of the prevailing law. This includes demolitions that are conducted without granting the aggrieved individual an opportunity to be heard, without a formal order passed by the relevant authority, or before the order was challenged in court. All demolitions conducted without adherence to this due process are extrajudicial in nature, and will form part of this research project. Additionally, the project will specifically look into extrajudicial demolitions that are punitive in nature, wherein, the intention is to penalise individuals or communities through demolition of their properties rather than through legal adjudication.

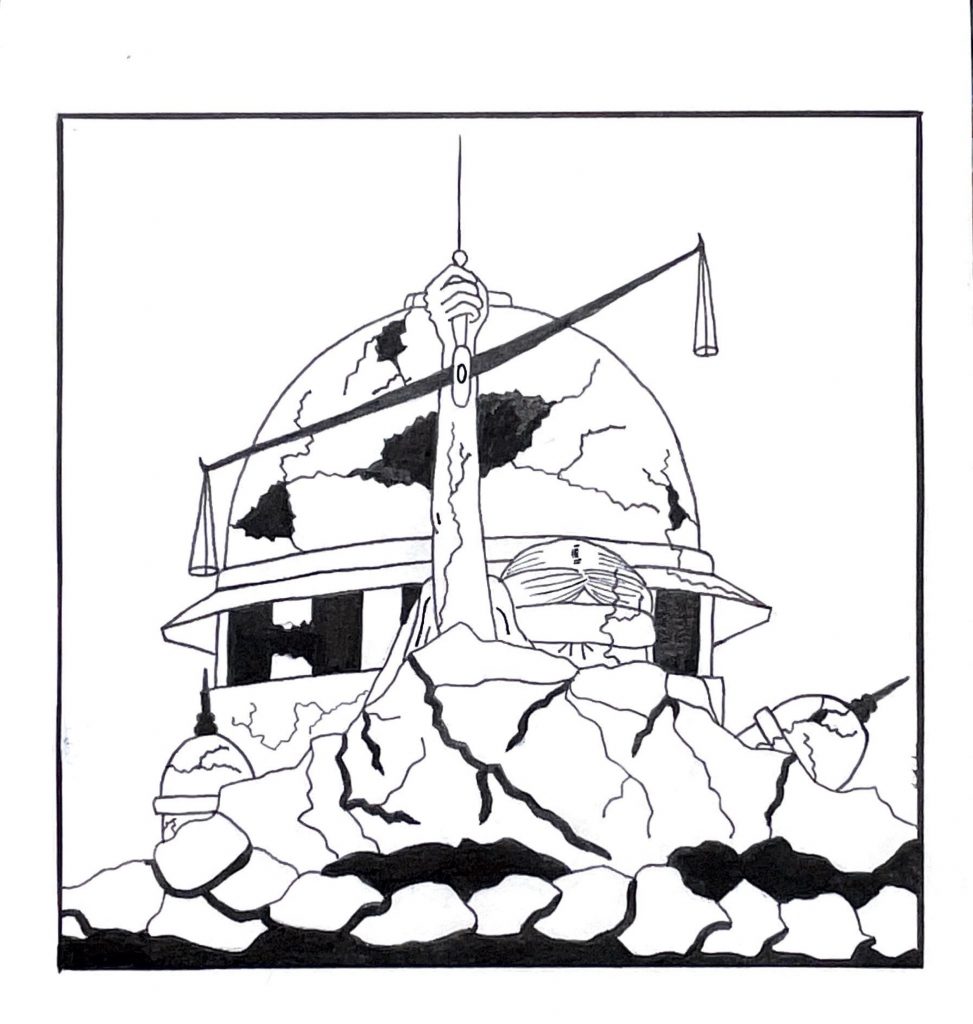

The prevalence and acceptance of extrajudicial demolitions as state practice stems from a culture of impunity. One of the primary factors enabling extrajudicial actions is the weak judicial oversight. Courts are either unable or unwilling to hold state actors accountable. Meanwhile, the aggrieved individuals face the additional obstacles of delays in legal proceedings, lack of access to justice, and instances of judicial bias. The result is a growing lack of faith in the judiciary, which is seen as emboldening state actors to act with impunity.

Yet, the right to due process, and the enforcement of it, is fundamental to democratic governance. The principles of natural justice are foundational to fair legal and administrative processes. It requires that state actions affecting an individual’s rights and interests be conducted in a fair, transparent, and lawful manner, without bias and with all individuals being granted an opportunity to present their case and respond to allegations against them. Extrajudicial demolitions consistently violate these principles, and the denial of legal recourse exacerbates the vulnerabilities of already marginalised communities, leaving them powerless against state action.

Thus, extrajudicial demolitions reflect and reinforce systemic inequalities in the country’s social, political and judicial institutions. In the absence of judicial oversight, and a lack of political will to challenge it, it is incumbent upon journalists, researchers and activists to document this egregious breach of constitutional principles and human rights. While evictions have historically targeted marginalised populations, the recent use of bulldozers has introduced a brazen, punitive aspect to extrajudicial actions that disproportionately target Muslims. In the process of documenting these demolitions and the lives of those aggrieved by them, this project will demonstrate the scale of violation of due process.