BK-16 Prison Diaries: Jenny Rowena on the fear of prisons and the Brahminical system behind it

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork.

As a space that takes away our liberties, marked by deep deprivation and suffering, the prison often gets framed as the point at which the liveable modern life ends. The fear of prisons, then, becomes all-pervading, with language itself constantly pointing to it as a dead end. Thus, for the ordinary person, the police and the prison system evoke extreme anxiety, and they design their lives to evade any encounters with it. Yet, those who come face to face with this system observe not an end, but the continuing flow of life inside, behind massive, impenetrable walls, even as their family and friends navigate a completely new reality outside. For academics like Hany Babu, the twelfth person incarcerated in the Bhima Koregaon case, who was active in social justice projects in the university space, the prison also offers a glimpse into the stark structural inequalities of Indian society and the many resistances against them.

It is becoming increasingly well known that the Indian judicial system is broken, and that jails are filled with undertrial prisoners, a majority of whom are from the most marginalised communities. Hany Babu, who is a Muslim, often writes about the huge number of Muslims in prison and how it has become the only public space in India in which Muslims are over represented. In fact, as a person who has fought for reservations within the university, he also makes another observation based on his incarceration in Taloja Central Jail—even as the inmates are mostly from non-savarna communities, the prison and judicial officers above them are almost always monopolised by savarnas.

Given this, as I got to know from Babu’s letters, the prison becomes a space of gross violation of human rights. While political prisoners, especially those who are middle class and educated, are accorded some respect and spoken to softly, the others are rudely addressed and treated with contempt and anger, and often even beaten up. As the prison officers and the judiciary are not exercising their power over their own caste and class, they face no real restraints or any pressure for accountability. As a result, they display very little respect for the basic human lives of the Bahujans who crowd the prisons. Here, from the stories we hear, people spend years and years as undertrials for the want of sums as meagre as Rs 10,000 and 20,000. As an unfeeling judiciary perpetuates a system that endlessly ensnares powerless Bahujans, a whole network of exploitative lawyers fleeces their relatives of their hard-earned money, often providing them nothing in return.

Moreover, very little is done to ensure basic facilities in prison, such as clean drinking water, palatable food, habitable and comfortable spaces, relief from the heat and the cold, and protection from seasonal diseases. The picture I have of Taloja from Babu’s narration is of a huge, overcrowded space, where barracks are filled with Bahujan bodies, many of them suffering from mental health issues; subjected to the extreme weather while being punished with bad food and colonial rules; and provided next to nothing in terms of legal aid, medical attention or psychological counselling. In such a situation, it would be futile to speak of recreation and means of self-improvement.

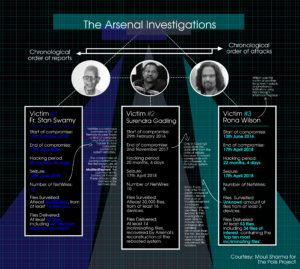

In fact, institutional murder is written into the very fabric of the Indian prison. Thus, not only do we have a situation where five people have died every day in police custody in the last decade, but many are also killed in cold blood by a Brahminical system that does not think it necessary to provide urgent, life-saving health care to Bahujans it holds in captivity. A classic example of this would be the death of Pandu Narote, a co-accused of GN Saibaba, who was suffering from swine flu and was shuttled back and forth from hospital to jail, and eventually allowed to die of a treatable disease. He was only 33 years old. Similarly, this is why even someone with as many supporters outside as Father Stan Swamy, perished in judicial custody, denied timely medical help. When Hany Babu had a COVID-related eye infection that became so serious that his left eye was swollen and almost popping out, it took us 12 days to get him out of the jail, to be checked by the doctors in JJ hospital.

In fact, even in ordinary times, many prisoners die of easily curable diseases due to sheer neglect. Surely if the prison was filled with upper caste/class elites, this would not have been the case. Given this, one can say along with Angela Davis, who reads prisons as racist institutions that need to be abolished, that the Indian prison is also a caste Hindu institution that does nothing for the betterment of society or the reform of its inmates, but only works to perpetuate existing hierarchies.

Moreover, in the Indian context, where a small minority of traditional elites struggle to maintain a gigantic democracy of aspiring and often resisting multitudes, the prison often becomes a space that manage resistance and dissent. So the crowding of Bahujans in prison not only tells us about a system that is prejudiced against them, but also about the way they are managed and kept in place. This is something Babu talks about in each of his letters, as he lives out his new life among a bunch of subalterns branded as criminals by the state.

In fact, it is an ailing economy and an oppressive social milieu (and which affects the dispossessed most, as Angela Davis notes) that gets coded as “crime” in most instances. For example, often, though not always, the thief, the gangster and the fraudster are those who push against the status quo of an unequal system, valiantly trying to rise above it. Whereas fraudulence, corruption and theft by the powerful go unpunished, while those who are less powerful fail to escape, and end up incarcerated. Seen in this way, crime can even be seen as an indirect form of resistance. In contrast to this, one also sees that those who are responsible for maintaining an extremely unjust system, and engaged in various illegalities within it, fall outside the purview of the notion of illegality itself. Even when they are brought within its fold, they manage to escape incarceration.

The case of political prisoners stands in contrast to these indirect resistances, for their dissent against the state and hegemonic culture is direct and brave. For instance, as Gladson Dungdung informs us, Adivasis form a majority of the 27,000 people arrested using UAPA (after being branded as Maoists), in central India, for openly resisting the state and corporate interventions into their lives and resources. In fact, many of the BK-16 who have also been framed as Maoists are activists who have aided such resistances. Similarly, the UAPA has always been used against Muslims, in order to keep the discourse of the terrorist alive, and locate the Muslim as a threat to the nation state. This is reflected in the arrests and incarceration of Muslim students, like Gulshifa Fatima and Umar Khalid, of activists like Khalid Saifi, of those who participated in the CAA-NRC protests, and of the hundreds of members of a now banned Muslim outfit, Popular Front of India.

Yet the story of the Indian prison cannot be confined to the inequalities that it perpetuates and the way in which it is used by the state to manage Bahujans. When one has a direct and personal encounter with such a mammoth institution of modern oppression, it invariably leads one to think more about the larger issues of contemporary existence. In fact, since the time he was interrogated by the NIA, I have watched Babu grapple with questions of freedom and captivity invoked by his police and prison experience.

Often, he remarks that freedom is more of an ideological construction than anything else, and that it eludes everyone, not just the prisoner. Foucault, a prominent philosopher of prisons, also imagines the hospital, school, asylum and the prison as similar systems of modern disciplining. Yet, such theorisation does not fully capture our reality, where we would rather be in a school, hospital or even a mental asylum, than in a prison. Perhaps, imprisonment is the only contemporary space where the illusion of freedom is not superimposed on the predicament of modern existence. The thought arises, then, whether it is the loss of this illusion that we fear when we fear prisons and live our lives in ways that try to avoid it.

The fear of prisons is integral to keeping the prison system alive, where the punishment is not just a matter of disciplining, but also the fact that you can be pulled away from your life, your workplace, your family and friends, and parked indefinitely in a space that neither you nor your dear ones can control. The illusion of control, choice and freedom, which makes modern lives real and liveable, shatters as soon as the police knocks on your door.

In fact, in the case of the BJP government and its postmodern politics of spectacle, this fear of prisons is constantly weaponised. As in the BK-16 case, cops hold press conferences, waving evidence on TV screens, sensationalising and circulating the news about political prisoners and their arrests. Thus, an entire generation of students, journalists, teachers, lawyers and intellectuals are tutored about brutal state power and its ability to wreck our “free” modern lives. A fear of prisons grows and further shrinks spaces of dissent and resistance.

However, even as prisons appear to be a dead-end, life continues even after imprisonment. For the poorest of the poor, who are the ones that fill our jails, a hard life gets even harder. Their relatives run around selling land and gold to save them and travel miles to meet them and the lawyers. Yet they share moments of love, even when tinged with deep anxiety and grief. They come to realize who their true friends are. Many bonds break even as new ones are formed. Many write long letters to those they have left behind. Some make cards out of gilt paper for the ones they love. Many celebrate birthdays with biscuits stacked up to resemble cakes. Sharp at 12 o’clock. Some build their bodies by using plastic bottles filled with water as weights. Some sing, some write songs.

The political prisoners, as in the BK-16 case, read endlessly, often bringing us books from the prison, which they have passed around amongst themselves. Many help other inmates in their legal cases. Both Hany Babu and Rona Wilson always bring for us a set of phone numbers, belonging to the relatives of inmates, for us to call and enquire about the status of their court cases. Both, I know, are responsible for helping many prisoners get bail. Babu also teaches English in jail.

For Babu at least, as he keeps telling us again and again, his incarceration has not only been highly unjust and unfair, taking him away from his family and robbing him of his work in the university, but it also has greatly enriched his life. He found his way back to Islam in jail, and now he is trying to learn Arabic and understand the Quran better. He also finds more time now to read, write and reflect, even though the very act of reading and writing is sometimes difficult as he has to sit on the bedding on the floor, and write with the book balanced on his lap.

Yet, in every meeting, he fills us with so many anecdotes and new thoughts and titles of books that we come back not only with tears but also the beautiful dream of being together again. It is then that the fear of the prison fades into the background and we realise that we have made our peace and “found love” and connection even in this “hopeless place”—as the famous pop song puts it. A love perhaps made more profound by the hope-filled, hopelessness of the situation.

The fear of prisons is generated by the effectiveness of its use as a tool of brutal repression against Bahujans, whose direct and indirect resistances against the status quo and state power is contained through incarceration. And yet, this fear itself is an important element in its success and circulation. More importantly, this fear pertains not only to the prison, but also confines and contains our “free” existences outside it.