BK-16 Prison Diaries: Vernon Gonsalves on the struggle to read and write behind bars

To mark six years of the arbitrary arrests and imprisonment of political dissidents in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project is publishing a series of writings by the BK-16, and their families, friends and partners. (Read the introduction to the series here.) By describing various aspects of the past six years, the series offers a glimpse into the BK-16’s lives inside prison, as well as the struggles of their loved ones outside. Each piece in the series is complemented by Arun Ferreira’s striking and evocative artwork.

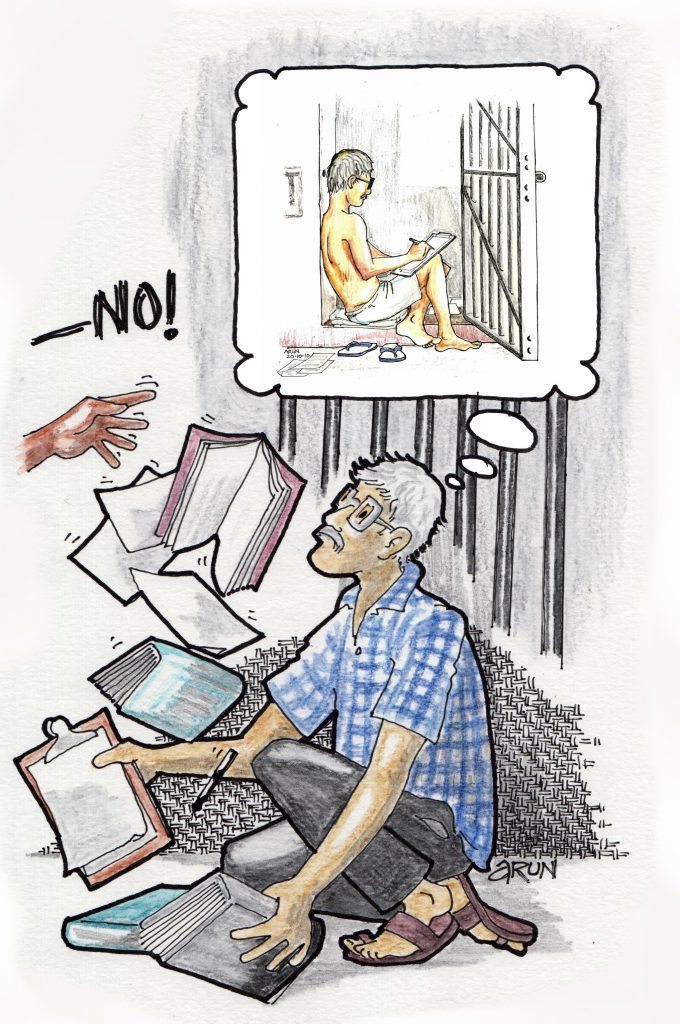

A prison peer-view that I cherish is a drawing by the artist Arun Ferreira, when we were fellow inmates of Nagpur Central Prison in 2011. He shows me sitting at the gate of my cell, writing-pad in hand, and writing—or rather, trying to write. It’s aptly titled, “Some Sophisticated Self-Deception.”

Perhaps I like it because it’s an image that I, like many other political prisoners, wanted as a prison self-image—someone who’s not wasting away his years behind bars. Someone who has some output, even if “only” intellectual output.

But such aspirations (or delusions) have to confront and cross sundry barriers put up by every prison administration. The prison system conditions the average superintendent or jailor to display a Pavlovian distrust of any form of cerebral activity among prisoners, particularly political prisoners. Writing materials, and even reading material, are seen with skepticism and suspicion, inviting restrictions and bans, which do not have any basis in any statute, rule book, or case law.

Of pens, papers and writing pads

Thus, after my arrest in 2018 in the Bhima Koregaon case, when I carried my trusty writing pad that had served me well during most of the years of my earlier stint in jail, it was disallowed at the gate itself of Pune’s Yerawada Central Prison. From my past carceral experience, I thought it was just the normal prison war of attrition over the instruments and means of intellectual production. The pad would be dumped in the jail godown, and after some pleading and prodding—and maybe a court order—I would be able to retrieve it.

But that was not to be. After sixteen months of requests before Yerawada prison officialdom got me nowhere, even my hopes of carrying it to Mumbai’s Taloja Central Prison, where I was transferred, came to naught. At the time of leaving, I was told that it could not be located. The loss of that yellow, dog-eared companion from my first prison term still hurts.

Pens, paper and other stationery items, like my precious writing pad, came to me piecemeal within six months of my 2007 arrest. This is extremely quick by prison standards. Rule 47(g) of Chapter XXXI of the Maharashtra Prison Manual specifically provides that prison canteens must be stocked with stationery articles, available for prisoners to buy. But prison officers ensure that these are rarely available, and then do all they can to block anything sourced privately.

However, I had benefitted from the battles waged by the political prisoners before me. Thus, back in 2007, though our pens and paper had been confiscated at the gate on first entry into Arthur Road Central Prison, Mumbai, we did not have to wait long. Ehtesham Siddiqui, who had led the struggle for basic prisoner rights, was the first to befriend us and provide the initial essentials of precious stationery from what he and his compatriots had fought for and obtained. Their efforts, at that time, had heralded a minor Prisoners’ Rights Spring, with inmates securing implementation of some long-denied welfare measures.

This raised the hackles of the prison superintendent, who bided her time and then, in June 2008, executed a planned attack on those who had stood up to her. The jail officials indiscriminately seized papers and other materials, broke the bones of Ehtesham and others, and banished them to different jails throughout the state. Perhaps, she hadn’t heard or wouldn’t heed the poet Neruda’s advice that crushing the flowers can’t really hold back the spring.

Of writing reaching beyond bars

Prison writing continues, in Arthur Road and elsewhere. But this requires engaging with the challenges of another frontline—the authorities’ attempts to ensure that prison writing does not reach the outside world. Many a story abound about the confiscation and destruction of manuscripts: whether through deliberate misinterpretation of Prison Manual censorship provisions; or surreptitious filching from prisoner possessions stocked in jail godowns; or even blatant strong-arm snatch-and-burn during barrack search operations.

The prisoner’s right to write and publish has been settled in favour of the prisoner way back in 1965 by a five-judge constitution bench of the Supreme Court in State of Maharashtra vs Prabhakar Pandurang Sanzgiri. The Bombay High Court, in 1984, has in Madhukar Bhagwan Jambhale vs State of Maharashtra, struck down as unconstitutional, the jailors’ powers to censor and withhold letters of prisoners due to political content or criticism of prison administration.

Nevertheless, prison superintendents persist in arrogating to themselves thought-policing and pen-policing powers they can have no claim to. Recently, in April 2024, the Maharashtra State Human Rights Commission (MSHRC) censured one such superintendent, who was sending the correspondence of all those accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, including Arun and myself, to the police Anti-Naxal-Operations (ANO) force, and withholding anything the ANO considered objectionable. On Arun’s complaint, the MSHRC declared the superintendent’s action to be violative of fundamental rights to equality, freedom of expression, and life and liberty. The commission advised that prison officers be educated regarding the law relating to censorship, and directed the superintendent and Maharashtra home secretary to pay a compensation of Rs 2 lakh to Arun. This case was about a letter to Arun’s mother, which had been disallowed in July 2021, where he had reminisced on the death of his co-accused Father Stan Swamy.

A fellow inmate, Abdul Wahid Sheikh, the author of the book, Begunah Quadi—which tells of the innocence of his co-accused, including Ehtesham, who had led the struggle for basic prisoner rights, and was sentenced to death in the case—writes of the horrors of prison torture, of manuscripts being repeatedly confiscated and turned to ash. Each written sheet that passes through prison bars faces similar, if not the same, challenges. While consuming any prison intellectual product, therefore, it would do well to keep in mind that, besides the mandatory sweat, it could quite well carry the hues of spilt tears, and maybe, spilt blood.

Of books, magazines and other reading material

Most attempts at writing require a good bit of reading, for which prison provides the time, if not always the environment. But no superintendent worth his salt can resist the temptation to arbitrarily find something objectionable in a book or magazine, and exercise power to block it, even if it is only because he has no idea what it may contain. Internet access, which is an essential for modern-day writing is, thus far, a strict no-no in Indian prisons.

Consider the plight of my co-accused, the octogenarian poet Varavara Rao. On his first entry to Yerawada Prison, he brought just two books – Tolstoy’s Selected Stories and Gulzar’s Suspected Poems. They were promptly grabbed from his hands at the gate and he was told to “request” the superintendent for permission to get them. During the days leading up to the weekly round, where he could make this request, Rao kept fretting that Suspected Poems, being a bit political, wouldn’t pass muster. On the appointed day, when he placed his request before the superintendent, with his phalanx of all the officers of the largest prison in Maharashtra, he was surprised that Gulzar, probably due to his Bollywood reputation, raised no suspicion whatsoever. But when he pleaded for Tolstoy, as an internationally renowned writer of classics, he met an insurmountable wall. “Main itna padha-likha kahan hun?” (I am not that well-read, am I?), the superintendent asked. An honest question, that didn’t lend itself to easy answers.

It is often this “honest” distrust of the unknown that is the average prison boss’s thumb-rule and that operates at every prison gate, preventing easy access to almost any reading material. In 2011, a deputy superintendent at Nagpur Prison even stopped my copy of the Constitution with commentaries, accusing it of being too bulky. He probably actually feared its potential for provoking disaffection against dictatorial prison regimes. However, after we spread the word that barring entry of a copy of the Constitution into prison indicated disrespect, meriting registration of a cognisable offence under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, the book was hurriedly permitted.

The law as regards reading material has been interpreted and laid down by the courts with ample clarity many decades ago. In 1963, the Bombay High Court held in George Fernandes vs State of Maharashtra that there could not be any restriction on the number of books that can be supplied to an inmate; and in 1966,in MA Khan vs State of Maharashtra, the same court laid down that an inmate could not be debarred from receiving and reading periodicals and books that could be freely received and read by the general public. These decisions still hold the field, but are mostly ignored by prison administrations.

Repeated insistence on observance of these judgments, and the orders sometimes obtained from the courts, have largely been the means by which prisoners manage to gain access to literature. My co-accused finally got his copy of Tolstoy, along with other literature, after approaching the trial court. The flow of literature for those in the men’s jails smoothened out after several such court applications succeeded.

But the experience with the women’s prison authorities has been different. Gender discrimination seems to reign supreme. Till recently, our women co-accused have had to obtain a separate court order for each book or consignment of books to enter Mumbai’s Byculla Women’s Prison. Few months ago, the requirement was lifted, but there is still a five-book monthly limit.

Perhaps it’s a particularly harsh reflection of societal bias against knowledge acquisition and production by women. Every piece of writing that clambers over a women’s prison wall had to get past a particularly rugged set of obstacles—and doubtless, it resonates all the more for it.