Speaking the Same Language: How ethnonationalism and Hindutva seep into the adjudication of citizenship in Assam

Himanta Biswa Sarma understands the assignment. Border states are crucial in the construction of a certain vision of nationalism, security and identity, and as the chief minister of Assam, Sarma knows his role in articulating that vision, and demonstrating why Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party are needed to protect it. “Infiltration from Bangladesh started in Assam 40 years ago,” Sarma said, at a press conference in Jharkhand on 15 May. “Now in Assam, the infiltrators’ number is 1.25 crore. This has become a big problem and Assamese people have lost their identity. We made a mistake 40 years ago, we didn’t protect our borders. You don’t let Rohingyas come in.”

Sarma’s speech was riddled with lies, communal rhetoric and fear mongering. He claimed that “infiltrators” had become ministers, speakers, and magistrates, and occupied up to 40 seats in the Assam assembly. “We are now fighting for our existence,” the chief minister claimed. “Stop infiltrators, otherwise within 20 years, across Jharkhand, the indigenous will become a minority.” This vision of national identity espoused by Sarma and the BJP assumes particular significance in today’s India, with its aggressive Hindutva and patriotic fervour—and especially so during election season, when votes are sought on these very grounds.

In April this year, just days after polling began, Narendra Modi launched into the brazen anti-Muslim, majoritarian rhetoric that marks the Bharatiya Janata Party’s election playbook, directly referring to Indian Muslims as infiltrators. The remarks drew wide condemnation, but it was not the first time he referred to Muslims as infiltrators. Ahead of the 2014 elections, too, Modi said “Bangladeshi infiltrators” would have to go back if he came to power. In November that year, he went to Assam and repeated the phrase, stating that infiltrators would be “pushed out.” Then before the 2019 elections, Modi again declared in Assam that he wanted to “free the country from infiltrators.”

But neither the prime minister’s speeches in the last two elections nor Sarma’s press conference received the same criticism as Modi’s speech in Rajasthan. In the border state of Assam, questions of security, identity and citizenship have long shaped its politics.

The fractured lines that the British carved out over the eastern part of the subcontinent have led to a perennial state of crisis in Assam—and one that lends itself to a transition from a decades-old ethnonationalist movement to the present-day Hindutva under the BJP. This overlap between jatiyotabad—an Assamese ethnonationalism built on anti-immigrant, anti-minority and anti-Muslim sentiments—and the Hindu nationalism of the Modi government, has turned the state into a testing ground for Hindutva policies and practice. This is particularly true for laws centred around citizenship, minority rights and majoritarian demographic paranoia. This year, Sarma repealed the Assam Muslim Marriages and Divorce Registration Act and announced his decision to bring a Uniform Civil Code in the state.

Perhaps most significantly, though, Assam as a Hindutva testing ground is reflected in the state’s National Register of Citizens, and its discriminatory adjudication of citizenship by the Foreigners Tribunals. The Modi government’s amendments to the citizenship and passport laws of India have already facilitated fast-tracked citizenship for non-Muslims from India’s Muslim-majority neighbours, and exempted them from being considered illegal immigrants for entering the country without a valid visa. As a result, the determination of citizenship in Assam, and its treatment of suspected foreigners, may create the model for citizenship across India, and one that would disproportionately affect Muslims.

With the Hindu nationalist notions of citizenship and belonging becoming part of the Indian state practice, and the Modi government expected to double down on these policies if it returns to power for a third term, it is increasingly important to study them closely. To understand the evolving jurisprudence of citizenship in contemporary India, I conducted an extensive analysis of 1,444 judgments of the Gauhati High Court, passed between 2013 and 2019, in writ petitions challenging the orders issued by the Foreigners Tribunals. The research studies how different litigants are perceived by the judges in the adjudications around citizenship in Assam, and its consequences.

It consisted of both qualitative and quantitative analyses of the high court judgments, providing valuable insight into the rationale of the court’s decision making, and revealing telling patterns in their judgments and interactions. For instance, by mapping the decisions by individual judges, I observed how judges from a certain ethnicity had dismissed more case than others. A demographic analysis of the suspected foreigners’ religion, gender and the outcome of their petitions revealed that the majority of Muslim and women petitioners lost their case before the high court. A close reading of 100 judgments laid bare how judges are not neutral arbiters deciding on law and facts, but are in fact active participants in the state’s exclusionary practices, often with prejudiced views of the petitioners and their witnesses.

Securitisation of migration in Assam

Assam has historically been marked by migration, and the fears manufactured around it. It is important to understand this securitised history to contextualise the adjudication of citizenship in the state today. The northeast of India was only annexed into the British empire in the early 19th century, and was, up until then, ruled by independent kingdoms that had not been a part of the greater medieval subcontinental empires. There was a diversity of religious practices, including Muslim rulers in several parts of the state. Muslims in the region assimilated themselves culturally, politically, socially and economically. It was only with the British conquest that Assam became a part of the colonial imperialist geography, who also introduced outsider and othering narratives about the state’s diverse demography.

The extractive nature of British colonialism led to them classifying lands that were not cultivated as “untapped,” not contributing to any commercial gains. The British propagated the notion of the “indolent” native, unwilling to work towards productive gains, describing them as predominantly primitive and incapable. Ethnic and religious categories began to assume importance in the administration of the province, with clear differences in the laws prescribed for the “civilised” plains people and “uncivilised” tribes from the hills. By 1874, when the British established the Commissionerate of Assam, they had already brought in upper-caste, upper-class Bengalis to fulfil administrative roles and responsibilities in the region. The indigenous middle class of the Assam region was sidelined, leading to ethnonationalism in the region, and sowing the seeds of the political instability that would arise in the region.

Pitting ethnic groups in opposition with each other had been a long-standing and well-documented approach of the colonial rulers. This was no different in the case of the immigrant peasant communities from East Bengal. In 1931, the British produced a widely-circulated fear-mongering census report about the “vast horde” of “land-hungry” Muslims who had invaded the state and displace the native population. This language had seismic consequences, finding its way into almost every discourse about the issue, and eventually, almost a century later, into the jurisprudence of India’s apex court. The securitised spectre of the illegal immigrant has thus been a part and parcel of the state’s political rhetoric since colonial times.

Following the Partition, there were further waves of migration from then East Pakistan. Quick on the heels of Independence, the virulent wave of cultural chauvinism that had taken shape in Assam continued to swell in proportion. The post-Independence rhetoric around Bengalis shifted to a border-centric discourse centred around immigrants. There were riots in the first few decades of Independence, as a part of an agitation that came to be called “Bongal Kheda”—Drive away Bengalis—marked by incidences of violence against the Bengali-origin population. This was also the time period when the political leadership of India had begun to frame the movement of people across the border as a national security concern. In 1950, the government introduced the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act to “provide for the expulsion from Assam of certain immigrants.” Thousands of Muslims were evicted from their homes and sent to East Pakistan, without trial. The first National Register of Citizens was prepared in 1951, by conducting a door-to-door survey and noting down people’s responses.

The Bangladesh independence war of 1971 led to the next wave of migration in the region. It led to a sharp rise in the number of refugees who crossed the border into Assam, which came into conflict with the pre-Independence reluctance to let outsiders into Assam. In particular, Muslim refugees were viewed with deep suspicion, even seen as agents of Pakistan sent to infiltrate the country.

Matters came to a head in 1979, an election year in parts of the state, when reports emerged that a large number of foreigners were listed in the electoral rolls. A group of students, the All Assam Students’ Union, and nationalist groups under the umbrella of the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad, came together to demand that the crisis of illegal immigration be addressed immediately. The movement called for foreigners to be “detected, deported and deleted.” The period between 1979 and 1985 witnessed intense protests, political polarisation, governmental instability and tragic instances of ethnic cleansing.

Finally, in 1985, the Assam Accord was signed between the leaders of the movement, the state government and the central government, providing for an amendment to the citizenship law that created three categories of Assamese residents: those who have been in the state since before 1966, those who entered between 1 January 1966 and 24 March 1971, and those who entered after the 1971 cut-off date. Only the individuals forming the first category were immediately treated as regular residents of Assam. Those falling in the second category would be deleted from the voter rolls for a period of ten years and those falling in the third category would be continuously identified and expelled from the state. This continues to govern the legal regime for determining citizenship in the state.

The quagmire of citizenship laws in India

The Citizenship Act, 1955 remains the guiding legislation on citizenship today. Its provisions lay down different avenues to citizenship, through birth, descent, registration, and naturalisation. While the controversial 2019 amendment to the act introduced the ground of religious persecution, the rules to implement the provisions do not stipulate any requirement to prove or declare such persecution. Following the Assam Accord, Section 6A was introduced to the Act, which codified the three categories and inserted the 24 March 1971 cut-off date into the law.

To prove their ancestry under Section 6A, suspected immigrants have to show that their ancestors arrived in Assam before this date, to a quasi-judicial body called the Foreigners’ Tribunal (FT). These bodies have come under sharp scrutiny, with multiple scholars and civil-society stakeholders pointing out that their functioning and constitution are in violation of principles of equality and fairness. FTs are riddled with substantive and procedural issues, which contravene all known principles of access to justice, transparency and fair trials. Their adjudication process, as I have discussed before in this publication, is notorious for its discriminatory and biased adjudications. Moreover, the state incentivises the tribunals to declare as many people as foreigners as possible, and contract renewals for its presiding members are directly linked to the numbers of people declared by them as foreigners.

FTs have been given the power to determine their own procedures. As a result, the set of standards that have evolved over the years has taken peculiar and dangerous turns. The first step in the process is the issuance of a notice to appear before an FT and establish one’s citizenship. This notice may be issued at the behest of the Border Police—a force assigned with the task of patrolling and defending the state’s border—or the Election Commission of India. The ECI also introduced the concept of the “D-Voter,” by marking certain voters as “doubtful” during the revision of electoral rolls, if it suspected any person’s ancestry. The D-voter tag compels the individual to appear before an FT, and it has been well documented that most of the people under this category are from ethnic (Bengali) and/or religious minorities (Muslims). Then, the trial unfolds, forcing an excruciating, opaque and hyper-technical documentary exercise, with no clarity on what forms of evidence are necessary to prove one’s citizenship.

In conversations with a number of people—including affected parties, their families, paralegal volunteers and lawyers—I found appalling stories about their interactions with the courtroom system. It is not uncommon for courts to reject valid documentation on the basis of minuscule errors—for instance, a difference in spelling, of say “J” to “Z,” across different documents leads to summary dismissals. Documents are subject to arbitrary evidentiary scrutiny, and oral testimony by relatives of suspected foreigners is often dismissed as made up. The burden of proving that one is not a foreigner is vested on the person suspected, in contravention of natural justice. The FT often cross-examines the person in ways that reflect inherent bias, using language that indicates an assumption of deceit.

Moreover, there is no mechanism in place to appeal orders issued by the FT. The only way to challenge the FT order is to file a writ petition before the Gauhati High Court—this is an important distinction, as it limits the opportunities for an individual to ascertain their citizenship before the higher judiciary.

That is not to suggest that the higher judiciary is infallible. In fact, in two notable cases of tremendous consequence, the Supreme Court has adopted the language and enforced the policies of Assamese ethnonationalism. The first was the now infamous 2005 case of Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court invoked the Constitution to pave the way for the disenfranchisement of an entire ethnic community, reflecting the deep-set entrenchment of religious xenophobia in Assam since colonial times. The court stated:

There can be no manner of doubt that the State of Assam is facing “external aggression and internal disturbance” on account of large scale illegal migration of Bangladeshi nationals. It, therefore, becomes the duty of Union of India to take all measures for protection of the State of Assam from such external aggression and internal disturbance as enjoined in Article 355 of the Constitution.

The other crucial case in this respect is Assam Public Works v. Union of India, which became the framework for updating the National Register of Citizens, and led to the eventual exclusion of 19 lakh people. The former chief justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi, himself from Assam’s upper-caste Ahom community, spearheaded the implementation of the NRC, leading the Supreme Court bench that assumed executive powers to monitor, supervise and administer the project. Following the publication of the final NRC, the state BJP government and the AASU have claimed that the process was compromised, while Muslim civil-society groups have argued that the list demonstrated the historic exaggeration of illegal Muslim immigrants in the state.

This is evidenced by the chief minister Sarma’s recent claim of 1.5 crore illegal immigrants in Assam. Two months earlier, Sarma had informed the media that the final NRC included seven lakh Muslims, five lakh Bengali Hindus, two lakh Assamese Hindus, and 1.5 lakh Gorkhas. The state government has not officially notified the NRC in the gazette, so there is no official confirmation about the breakdown stated by the chief minister. The official notification of the NRC is expected to bring down the number of exclusions—and therefore the number of illegal immigrants officially recorded in the state—in the subsequent appeal processes. There is still no clarity on when the list will be notified.

Meanwhile, the union government passed the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019, and its rules in March this year. Given the issuance of the rules, it has been argued that the Hindus who are excluded from the NRC can now achieve a path to citizenship. This presents the peculiar paradox that the same people who were making claims to citizenship under the NRC framework would now have to position themselves as immigrants.

In creeping authoritarian contexts, the danger of lists of citizens with their personal and demographic information has already been witnessed over and over again, especially in the context of ethnic cleansing. In the context of India’s Hindu nationalist transformation, we are likely to see a large-scale application of CAA for legitimising Hindu citizenship, thereby moving away from the secular and egalitarian ideals of the Constitution. On 15 May, the home ministry already issued the first set of CAA certificates under the new amendments to 14 people, granting them Indian citizenship.

Studying the jurisprudence on citizenship

It is crucial, then, to understand how courts interpret and enforce the laws of citizenship. I chose to study the Gauhati High Court for two important reasons. First, it is one of few courts of record in the country looking at citizenship and foreigners’ matters. Given the precedential value of its judgments, it is essential to examine its jurisprudence. Second, and more related to the unavailability of sources, the Gauhati High Court orders are more publicly accessible than those passed by the FT. In fact, studying them often provides insight into the FTs jurisprudence as well.

I closely and comprehensively examined how the Gauhati High Court has adjudicated citizenship. The dataset I used came from DAKSH India, a think tank that studies, among other things, judicial decision-making patterns, in 2020. At the time, they were able to scrape out data from over 1,470 judgments from the period 2013–2019, which they shared with me. After leaving out a few irrelevant or interim orders, I was left with 1,444 judgments, which formed the database for my quantitative analysis.

The data was, in a small percentage of cases, insufficient to measure any demographic indicators, but by and large, I was able to identify ethnicity, religion and gender from the names and pronouns in the document. I then used this data to study the patterns between the final outcome of the cases, and the demographic identities of the petitioners and judges.

From the larger data set, I also randomly identified 100 cases for a closer qualitative analysis. I adopted discourse analysis, which has long been a part and parcel of legal anthropology. In simple terms, this method relies on the analysis of the power structures embedded in the language of text, which can take many shapes such as transcripts, courtroom documents, petitions written by the lawyers defending people’s citizenship, edicts of judges and so on. By closely scrutinising the language adopted by the judges, I identified patterns that reflected the judge’s own positionality as well as the power structures embedded in the citizenship proceedings. Moreover, the text of the Gauhati High Court’s judgments often contained excerpts from the Foreigners Tribunal order, thus allowing me to compare the language used by the two bodies.

Through the research, I answer the question: how are different litigants perceived by judges as they become political actors in the adjudications around citizenship in Assam, and what are the implications?

What the numbers say

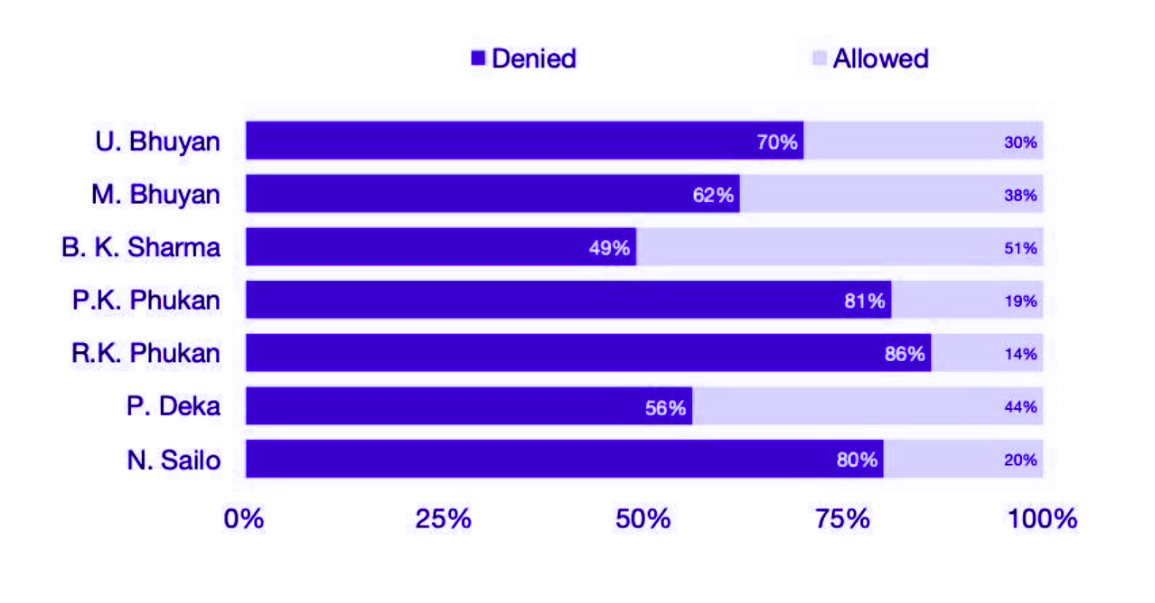

The data from these judgements suggests a tendency towards declaring people foreigners. Of the total number of petitions that were filed, only 39% were allowed or partially allowed, with 61% unceremoniously dismissed. I was able to identify seven high court judges within this dataset who heard and gave verdicts on the writ petitions. On an average, it was found that judges are likely to dismiss the petitions in 70% of the cases they oversee. Ujjal Bhuyan presided over the maximum number of cases in the database, sitting on 614 of them as part of division benches with different judges, and Nelson Sailo heard the least, with 116 cases.

Even a perfunctory scan of the names of these judges reveals that they are overwhelmingly from the Hindu upper-caste Assamese community. The judges displayed a predilection to focus on a securitisation rhetoric, condemning minorities to live in a twilight zone, suspended between citizenship and statelessness. Further, the writ petitions that did end up being allowed only led to the petitioners being sent back to the same FT that had declared them foreigners. This Sisyphean process can continue relentlessly, denuding them of scarce resources, money, and years—even decades—of their life as they shuttle from courtroom to courtroom.

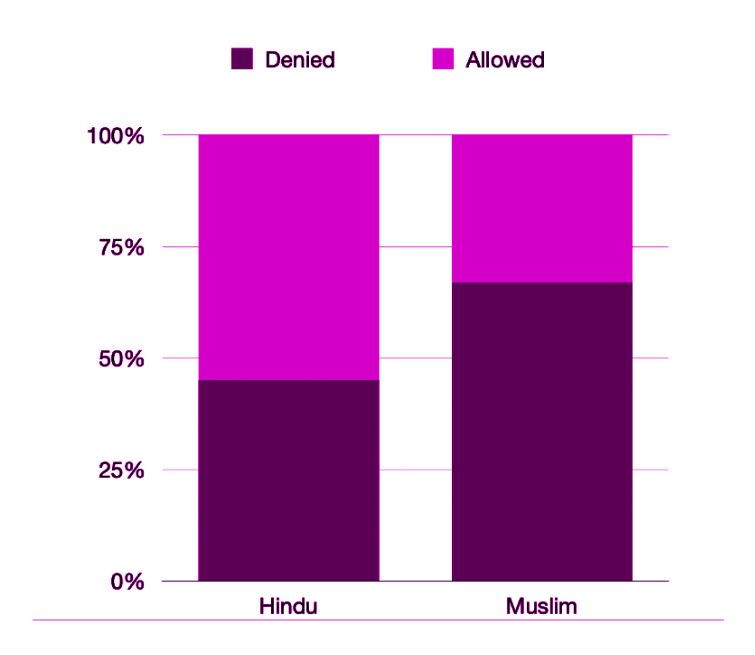

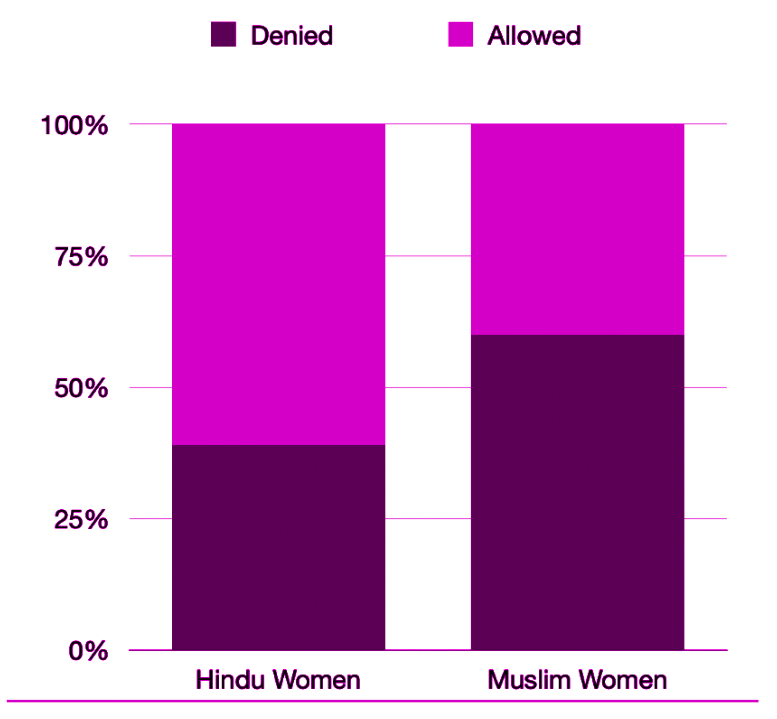

In terms of religious categories, I identified the religious identity of the petitioner in 862 cases from their name, but in many instances, the raw data set had the name redacted. The research revealed that 67% of the petitions filed by Muslims were dismissed, and only 33% succeeded—which in most cases meant they were sent back to the FT. On the other hand, 55% of the cases by Hindu petitioners succeeded, and 45% were dismissed.

Muslim women, in particular, bear the brunt of having to figure out ways to present a convincing case before a hostile court. Only 37% of petitions by women were allowed, and the difference was very slight for men, with just 40% of their petitions allowed and approximately 60% dismissed. On adding the intersection of religion to this analysis, the contrast becomes much starker, with around 60% of the petitions of Muslim women being rejected, as opposed to 39% in the case of Hindu women.

The judicial construction of the spectre of immigrants

By studying the language and rhetoric of the court, it is possible to pierce the veil of the neutrality of justice, which is writ large, not just in first-year law school classrooms, but also in the political imagination. To do so, I adopted the framework of stancetaking—a research method within the discourse analysis school that argues that the language used by judges in court displays their biases and perspectives. Language has deep roots in society and culture, and by studying the Gauhati High Court’s judgments on citizenships through this lens, it is possible to examine whether the judiciary and the adjudicatory process reflect specific positions in societal hierarchies. From this investigation, I was able to draw out clear patterns in the ways in which the judges chose to utilise language in the courtroom.

Assumption of deceit

Judges seemed quick to assume that a petition was guilty because of the verdict of the subordinate FT. There is a tendency for judges to use language that is indicative of a deep distrust of the petitioner. This leads them to dismiss every piece of evidence put forward. Take this extract from Abdur Rashid v. Union of India:

While under Section 79 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 there is a general presumption regarding genuineness of certified copy, the fact remains that a large number of fake certified copies have [been] detected in the State of Assam in recent times where the process of updating the National Register of Citizens (NRC) is presently on. This has led to registration of criminal cases against the culprits involved in making of and procuring fake documents. Therefore in the above factual scenario, notwithstanding such presumption, the Tribunals as well as the Courts would have to be very careful while scrutinising such documents.

The court has, on record, advised FTs to disregard the provisions of the Indian Evidence Act, and the positive presumption mandated by law, encouraging them instead to question the veracity of certified copies, effectively reducing the scope for establishing citizenship. Moreover, some documents that are provided need to be proven by the issuing authority. A common piece of evidence submitted, especially by women, is a certificate by the village headman or Gaonburah, who then has to be presented before court. This is often an uphill challenge it itself, which is compounded by the court’s predilection to dismiss it. Similarly, discrepancies in documentation as a result of bureaucratic mistakes were catalysts towards an assumption of deceit as well.

The assumption of deceit is also on display when judges examine the testimony of witnesses before the FT. According to Section 50 of the Indian Evidence Act, “the opinion, expressed by conduct, as to the existence of such relationship, of any person who, as a member of the family of otherwise, has special means of knowledge on the subject, is a relevant fact.” However, the court by and large dismisses statements by relatives, including parents, spouses and children.

In another case, Shamela Khatun v. Union of India, the court assumes that the petitioner is lying when she mentions that her counsel did not advise her properly. The judge notes, “Coming to the Writ Court the petitioner has taken recourse to falsehood by blaming the engaged counsel unmindful of the fact that Section 9 of the Foreigners Act, 1946, the burden of proof lies on the proceedee to establish that he/she is an Indian citizen.” (sic) The judge seems to ignore the assertion the petitioner’s submission that she engaged a lawyer who misled her into believing that she did not need to appear before the FT, and that she only discovered later that she had been declared a foreigner ex parte, without being heard.

During my research and reporting, personal interviews have corroborated that in many instances, FT lawyers are not equipped to defend their clients properly, and the clients do not know the nuances of the citizenship laws, such as the burden of proof. In a series of interviews conducted between 2020 and 2024, many litigants spoke about how their advocates created the greatest challenges in their case due to their indifference, apathy or incompetence. In these circumstances, it is pertinent and concerning that the court decided the case assuming that the petitioner was lying.

Heavy burden to be the perfect litigant

The judges impose and apply a certain standard of what they believe an ideal citizen looks like. However, similar to the proceedings in the FTs, this standard seemed rooted in the judges’ own ideology, allowing very little room to manoeuvre for anyone who does not fit within this model. For instance, in one case when the appellant could not appear before the Foreigners Tribunal because of illness, the court said that there was “no reason given by the appellant why at least her husband could not appear before the Tribunal and explain that his wife (appellant) was not well and that the matter should be adjourned.”

The law does not compel a spouse to appear and explain their partner’s absence, as suggested by the court, and the judge does not take into consideration that the husband may have been required to attend to his wife, or that he could not afford to take leave from work. Yet, the court goes on to state, “The appellant and her husband have taken the matter very casually.”

In Zabeda Khatun v. Union of India, the court dismisses an entire set of voter list documents because of discrepancies in the names of the petitioner’s parents. Even when there is consistency that points to the veracity of the petitioner’s claims, the judge focuses only on the discrepancies. The judge writes:

In the voter lists of 1966 and 1970, the name of wife of Sattar Bhuyan is shown as Aymon Nessa (mother of the petitioner), whereas in the voter list of 1997 her name is shown as Zamela Begum. The petitioner failed to furnish any explanation before the Tribunal. On that count also, the plea of the petitioner that Sattar Bhuyan and Abdul Sattar are one and the same person is not acceptable.

The court expects perfect consistency in the paperwork of litigants. This is challenging, because “surnames are often in a state of flux in the Bengali-Muslim community,” a paralegal working on the ground told me. “Our surnames are often altered at will, and thus look different in different records.” However, the court does not seek to engage with the realities of the petitioner on the ground, choosing instead to focus on the minutiae of documentary evidence.

Ex-Parte Orders

In legal parlance, ex-parte orders are those issued in the absence of the person suspected. In the given dataset, there were 688 judgments challenging ex-parte orders passed by the FT, in the complete absence of the petitioner. In 2013, the Gauhati High Court held, in Moslem Mondal, that ex-parte orders may be set aside in the interest of fairness and justice, in case of special or exceptional circumstances explaining a petitioner’s absence. The judgment opened up the space for the court to be lenient in challenges against ex-parte orders. Lawyers and paralegals whom I interviewed said the judgment led to a noticeable trend of the court being much more likely to remand an ex-parte case than not.

Nonetheless, judges adjudicate on ex-parte matters at their own discretion, despite the Moslem Mondal guidelines. In some instances, courts are quick to acknowledge defects in the notice served to litigants to appear before the FT, or the Election Commission and Border Police’s reference process, and send the cases back to the FT. In others, it ruthlessly dismisses ex-parte orders. Among the 100 cases randomly selected for the qualitative analysis, in at least 12 different judgments authored by the judge Manojit Bhuyan in 2018 and 2019, the court observed the following verbatim:

We find that sufficient opportunities had been granted to the petitioner to establish his claim as not being a foreigner. In this context, we may observe that although the procedure of identification and for declaring an individual to be a foreign national cannot be relegated to a mechanical exercise and that fair and reasonable opportunity must be afforded to a proceedee to establish claim that he/she is a citizen of India, however, such grant of fair and reasonable opportunity cannot be enlarged to an endless exercise. A person who is not diligent and/or is unmindful in taking steps to safeguard his interest, he does so at his own risk and peril. In the instant case several opportunities were granted to the petitioner to establish his claim, which he utterly failed to do so.

This rhetoric of “sufficient opportunities” flies in the face of the common law precept that ex-parte orders deprive people of their fundamental right to be heard, leading to one-sided argumentation. The court burdens people who are often navigating such a bureaucratic goliath for the first time with the pressure to be intimately involved with procedural law. This is not reflective of the reality on the ground, where most people do not understand what is being asked of them in court, or where their case is headed. The fact that the paragraph is repeated time and again also raises questions about the judge’s determination of “sufficient opportunities,” and whether the unique circumstances of each case were taken into consideration.

There were also two cases where the petitioners said they were suffering from mental health conditions that prevented them from being able to appear before the Tribunal, leading to ex-parte orders declaring them foreigners. In Hasen Ali v. Union of India, the court recorded the submission, including the medical certificates submitted by the litigant.

The petitioner stated that for his mental ailment he took treatment through ‘Kabiraj’ in his village and as his abnormality increased, from 24.04.2016 onwards, he started attending the Mental Health Clinic at Goalpara. He stated that the Medical & Health Officer, Civil Hospital, Goalpara on 13.10.2017 issued medical certificate stating that he is suffering from Schizophrenia and is taking treatment from Psychiatric OPD, Goalpara Civil Hospital since 21.01.2016 and that he is under medication. As allowed by this Court, the petitioner filed an additional affidavit on 05.03.2018 and named a ‘Kabiraj’ under whom he was taking treatment prior to 24.04.2016. The petitioner, by placing those medical certificates and prescription, tried to establish that there is no negligence and default on his part in pursuing his case before the Tribunal.

Yet, the court refused to regard any of this as relevant, and dismissed his petition. In contrast, in the other case, Kuldeep Saha v. Union of India, where the petitioner puts forward similar grounds, the court adopted a much more lenient tone.

If it is proved that the petitioner is mentally ill, the petitioner must get benefit for such mental health and he should be given opportunity by referring the matter back to the tribunal for rehearing of the case by giving adequate evidence in support of the case. In the written statement that was filed before the Tribunal, the petitioner also took the ground of mental sickness. Although, there is no specific provision for setting aside an exparte order. The Full Bench of this Court in the case of th e State of Assam Vs. Moslem Mondal… has held that under certain circumstances, an order of ex-parte can be set aside.

THUS, A DEEPER investigation of the language of the court reveals that it is steeped in the prejudice endemic to the ethnonationalist leanings within Assam. While the rest of the country protests the CAA due to its failure to protect Muslims, in Assam, the discussion centres around not allowing anyone in through its borders. The judges of the Gauhati High Court reflect this wider societal bias through their judgments.

Since this is the only avenue to challenge an FT order, and the High Court is a court of record whose judgments hold precedential value, it is crucial to reform the entire framework around citizenship adjudication. It is imperative to do away entirely with the Foreigners Tribunal, and introduce a more transparent, fair and equitable adjudication of citizenship disputes. The Gauhati High Court is in need of sensitivity training for its judges, and greater structural reforms in terms of appointments, representation, diversity and equity and so on.

Citizenship issues are not criminal issues, and do not deserve to descend into a “crimmigration” space, where civil offences have disproportionate criminal penalties. The state has to make clear what documents it considers as valid for adjudicating upon citizenship or immigration. India needs to sign and ratify the triumvirate of the Refugee Convention, as well as the two main United Nations conventions on statelessness. Given that our constitutional bedrock consists of the right to equality, right to a fair trial and right to life, among others, we must disband all detention centres, and bring an end to discrimination on the citizenship front. The long road to ending statelessness has to begin immediately, lest our constitutional ideals and human rights obligations irredeemably fail in the long run.

The author would like to thank Padmanav Baruah and his team, Anushka Agarwal and Shrishty Chhaparia for their research assistance.