The “official” (police) version of events: Excuses, reasons and actual causes of custodial deaths -2

“Akira Kurosawa’s classic ‘Roshomon’ is a reminder that there are several versions of the same story, each seeming right, depending on who is saying it, when it is said and from what standpoint.”

Dr. S. Muralidhar, Judge, High Court of Delhi, The Trajectories of Criminal Law.

In part two of this series, we focus on police narratives, or on the “official” version of events. We explore the excuses, reasons and causes of death according to the Police and other state bodies in all 15 cases. In this essay we discuss data on the types and frequencies of different official causes of death in police and judicial custody. We also highlight the various kinds of torture inflicted on persons in custody, and include studies on police biases against individuals from certain sections of society.

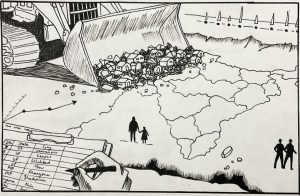

The Police in India often attribute deaths in police or judicial custody to “natural causes”. Viral infections, suicides, asphyxiation and other reasons are common causes of deaths, according to the Police. As mentioned in the first essay of this series, 22-year-old Altaf hung himself from the water pipeline using the string of the hood of his jacket according to the Police. Such bizarre and illogical reasoning is not uncommon when it comes to official custodial death narratives by the Indian police. In a scenario where the victim does not have the agency or the ability to voice the truth and their families are under pressure from the Police, the Police version of events becomes the official and often repeated narrative. However, postmortem reports and testimonies from family members provide evidence of widespread police brutality and torture. Cases of bribery and corruption to prevent the families from filing a formal complaint are common and so are threats to families who do file a complaint against the Police.

The National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) Crime in India (CII) reports use data reported from police stations across the country; these, however, may not always be transparent and accurate as discussed in the previous essay. The 2015 CII report provides the reasons for custodial deaths. Suicide was listed as the highest in 34 cases, followed by hospitalization in 12 and illness in 11. Natural deaths were listed in nine cases and in six it was injuries due to physical assault by the Police when the victim was in police custody. Death due to escaping from police custody was listed in five cases. Similarly, the 2016 CII report lists suicide as the major cause of custodial deaths in 38 cases, followed by illness in 15 (outside the hospital) and 13 (inside the hospital). Injuries sustained due to physical assault by the Police are listed as the reason for deaths in eight cases and natural deaths are listed as the reason in seven cases. Political scientist Jinee Lokaneeta, while highlighting the case of the death of Jishan, a Muslim man who died in February 2022 in Delhi’s Tihar Jail, discusses the use of “natural causes” as the official reason for death. Lokaneeta calls for an urgent re-examination of the category and mentions that even though there were visible external and internal injuries on Jishan’s body, his death was categorized as “due to natural causes.” The postmortem report in Jishan’s case did not draw any inferences from the mention of external injuries, which were clearly produced as an effect of physical assault and not by natural causes as the Police claimed.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in the state of Jharkhand. After two days in police custody, he was finally taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries where he was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016. In Ansari’s case, the Police initially said that the cause of death, as a provisional diagnosis, was likely to have been encephalitis, a viral infection. However, the postmortem report stated the presence of internal and external injuries caused by a hard and blunt object. The initial injury report dated 6 October 2016 confirmed this. According to court documents that we accessed for this case- specifically the case diary highlighting sections of the Criminal Investigation Department investigation – in the timeline of events, evidence and witnesses pointed to Ansari being arrested on 3 October 2016. However, the police station records showed his arrest on 4 October 2016 at 1:15 PM local time.

In a letter dated 26 September 2017, doctors at the Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS), Ranchi commented on the postmortem report. The letter noted that the external abrasions caused were grievous in nature and the external injuries are “not sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature.” The cause of death is the combined effects of injuries and their complications in the form of congestions, hemorrhages and necrosis in the brain, kidney, liver and gastrointestinal tract. The autopsy report did not find any evidence of either encephalitis or any viral infection.

P. Ramkumar, from Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016. He was arrested in connection with an alleged murder on 24 June 2016. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a high-security prison, a week before his judicial custody expired. He was brought dead to the Government Royapettah Hospital in Chennai, and the Police claimed that he had killed himself. They claimed that around 5 PM on 18 September, he was allowed out of the dispensary block where he was being held after he asked to drink some water, which was when he allegedly broke open a switchboard and bit into electrical wires, leading to his death by electrocution. Reports said that a constable who claimed to have opened the door to the dispensary block and two prisoners had given eyewitness statements. The statements claimed that Ramkumar was brought to the prison doctor in an unconscious state before being taken to the hospital, where he was declared dead. According to the Human Rights Advocacy and Research Foundation’s fact-finding report, the Police’s version of Ramkumar’s death by suicide in the high security Puzhal Central Prison in Chennai on 18 September 2016 was highly questionable.

On 19 September 2016, Ramkumar’s father, Paramasivam, filed an injunction requesting a doctor of the family’s choosing to conduct Ramkumar’s postmortem examination. The Court, however, rejected this plea stating that the postmortem could be conducted by an expert from the Delhi All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Delhi and aided by doctors at Royapettah Hospital. The postmortem report concluded that Ramkumar died due to electrocution and noted a dozen electrical burns. It did not point to any additional injuries.

Ramkumar’s family and medical experts have dismissed the findings of the postmortem as false. Sampath Kumar, the head of the forensics department at Saveetha University, who has been an expert investigator in many of Tamil Nadu’s most controversial cases, told journalist Sujatha Sivagnanam at The Caravan, that Ramkumar almost certainly did not die from electrocution. Kumar also added that the switchboard that Ramkumar allegedly broke open was more than six feet from the ground. To bite into the wires, Ramkumar would have had to yank the wires down with his hands, which would have led to other electrical injuries that are not noted in the postmortem report. Kumar had been nominated by Ramkumar’s father as expert witness during the postmortem, but the Court did not allow him to attend. It took four years of legal proceedings and protests by Dalit organizations for officials to finally share the postmortem report with Ramkumar’s family and legal counsel. The Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission (TNSHRC) took cognizance of the case five years later. In August 2021, the two histopathologists who had examined Ramkumar’s body immediately after the postmortem deposed before the TNSHRC. Their report contradicted the findings of the postmortem. According to them, none of the body tissue collected, including from Ramkumar’s lips and tongue, suggested any damage by electrocution.

Abdul Khader, the casualty medical officer at Royapettah Hospital who examined Ramkumar’s body, also deposed before the TNSHRC. During his cross examination, he made several claims that contradicted the police account. He said that there was no evidence suggesting that Ramkumar had been treated at the prison clinic. Moreover, rigor mortis had started setting into the body, which usually starts only twelve hours after death. He also told the TNSHRC that the injuries he saw were not electrical injuries. Shortly after Khader’s cross examination by the commission, R. Anbalagan, the jail superintendent at Puzhal, asked the Madras High Court to issue a stay order on the inquiry, which the Court granted. According to a report in The Caravan, R. Thomas, Anbalagan’s advocate, said that they had opposed the inquiry because the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) had already conducted a probe into the case. The three medical reports produced by the hospital Ramkumar was taken to indicate that he had a deep cut on the right side of his neck and a smaller one on the left side. The full report of the TNSHRC is still not publicly available.

Shameel Basha, 26, was picked up by the Pallikonda Police from Vellore on 15 June and detained in police custody till 18 June in connection with a missing person’s case of a former colleague. He died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 26 June 2015 following health complications which he reportedly developed while in police custody. The NHRC noted that the inquest report revealed injuries on the victim included swelling on the right chest, blood clot on the left hip, blood clot on the left back, blood clot on the right shoulder band, injuries on the right-hand wrist and right-hand elbow. It also suggested that the injuries were caused due to a stick or lathi. The postmortem report revealed several abrasions and contusions on different parts of the body and the final cause of death, based upon the viscera and histopathology report, was due to complications of multiple blunt injuries. The magisterial inquiry report conducted by the Judicial Magistrate, Vellore, also concluded that the deceased appeared to have died of complication and multiple blunt injuries. The NHRC observed that the deceased had died due to custodial torture by the Police of the Pallikonda police station and was of the opinion that “the State is vicariously liable to compensate to the next of kin of the deceased.”

Meenkulambu Karthik was picked up by the Police for a robbery in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. Hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. The Police, based on CCTV footage, established that Karthik was one of four people who were accused of snatching the chain of a female techie, two days before his death. Karthik was detained at the Kannagi Nagar police station for questioning and his family was told two days later that he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. The hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. Those who knew him alleged that Karthik was innocent and that his incarceration and death was a case of police brutality and murder.

After Karthik’s death, the family claimed that they were given a bribe by the Police from the Kannagi Nagar police station to refrain from pursuing a complaint on the issue. According to a September 2016 news report, Ganga, Karthik’s mother, said that the family was offered an amount of Rs. 400,000 by policemen at the Kannagi Nagar police station. Ganga alleged that an amount of Rs. 200,000 was given to the family as a bribe, and another Rs. 200,000 was offered to them. Ganga filed a complaint with the Police Commissioner regarding the custodial death of her son. She stated in her letter of complaint that when she saw her son’s body at the Rajiv Gandhi Government Hospital, it was covered with injuries including on his head and thighs. The complaint also stated that his right leg was broken.

In her complaint, Ganga said that on 19 September 2016, Karthik left the house saying that he was going to buy a sim card. The following day, some people living nearby told her that Karthik and his friend Arunachalam had been arrested. When she went to Kannagi Nagar station at around 1:30 PM, the Police told her that he was not there and had been taken to another station for investigation. They also told her that her son was lying to the Police and was not cooperating with them. On 21 September, she said that the Police had told her that during the robbery, her son had suffered some injuries and had been admitted to Rajiv Gandhi Government Hospital, and on that same night she found out that her son had died. On 22 September, she was finally allowed to see her son’s body at the hospital. Ganga stated that she then went back to the Kannagi Nagar police station on the same day to file a complaint in regard to his death, but the Police did not file a complaint. They also did not show her the FIR filed against Karthik and Arunachalam. In her complaint, Ganga has named two policemen – sub-inspector Bhagyaraj and head constable Vijaykumar – of the Kannagi Nagar police station and blamed them for Karthik’s death, possibly due to the injuries that she saw on his body and due to the bribe amount offered by the Police.

Kuppuswamy, a petty shop owner from Sanarpatti in Dindigul district, was arrested by the Police for allegedly selling liquor illegally. Subsequently, Kuppuswamy was remanded and lodged in Madurai prison in Tamil Nadu. While in custody, the Police had called his family members and informed them that Kuppuswamy had died due to illness. His family refused to buy the Police claim of natural death and staged a protest in front of Sanarpatti police station. They also condemned the Police for arresting him in a false case. During the protest, a family member said that policemen had brutally assaulted Kuppuswamy and that he sustained serious internal injuries and eventually succumbed to them. “Hence, the personnel involved in the abuse and attack of Kuppuswamy should be suspended and a proper investigation should be conducted into his death”, said Kuppuswamy’s family while also demanding monetary compensation. However, the Police have refuted the charges of custodial death. A senior police official claimed that Kuppuswamy was suffering from nausea and from a serious ailment. He was immediately rushed to Madurai Government Royapettah Hospital but died on the way. The Sanarpatti Police corroborated the view of the senior official and a source at Sanarpatti police station claimed that Kuppuswamy was weak and suffering from a serious ailment even during the time of arrest.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Police in Tamil Nadu. He died a few hours after he was picked up and taken for questioning on 3 September 2015. According to reports, Mohan was assaulted by the Pallikaranai police personnel during an inquiry and fainted in the station. By the time the Police took him to the Global Hospital in Perumbakkam, Chennai, he died. Mohan’s body was then shifted to the Government Royapettah Hospital for an autopsy. The Police, however, maintained that Mohan died of a cardio-pulmonary arrest. The Police managed to get it in writing from Mohan’s partner that he had died of a cardiac arrest. They also promised monetary compensation and a job for her eldest son.

Bujji, who was taken into police custody for his alleged role in the fatal stabbing of the Hosur Town police station head constable, died within a few hours of his capture, on 15 June 2016. While allegations arose that it was a case of custodial killing, the Police said the 19-year-old had died as a result of a cardiac arrest while in custody.

Gokulakannan, 22, was a contract laborer from Karumalaikoodal village in Tamil Nadu, who was picked up by the Police in connection with a murder. He was picked up around midnight and was rushed to the Mettur General Hospital in Salem, and later to the Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College Hospital in Salem, where he was declared “brought dead.” He died on 6 June 2015. Local activists said that the Police threatened and bribed the family to take back their allegations of custodial torture.

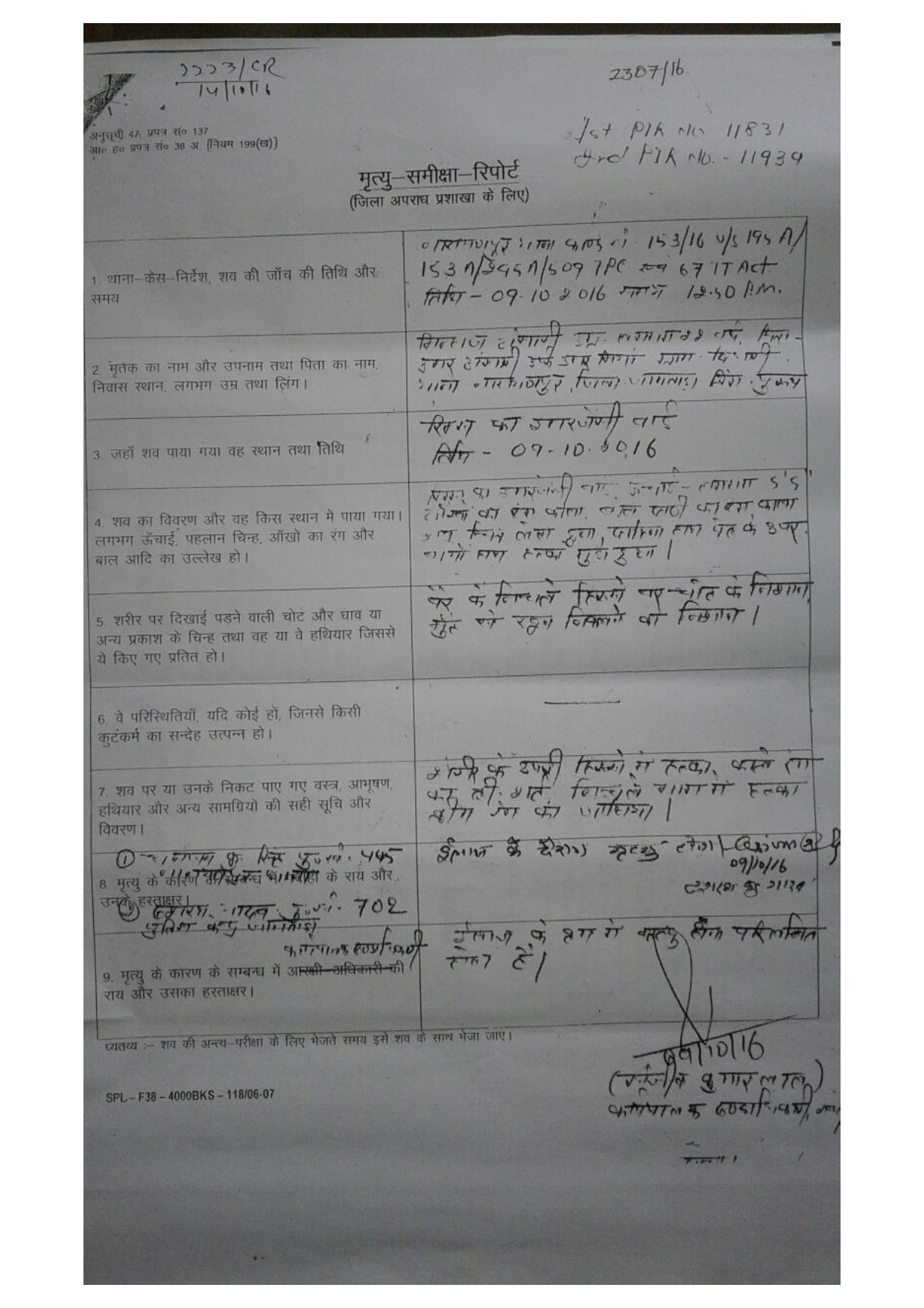

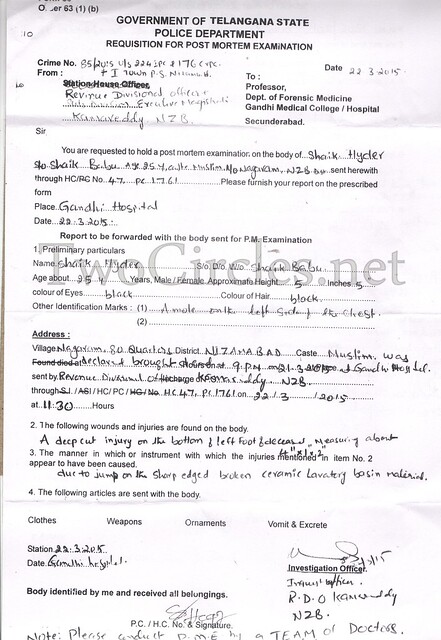

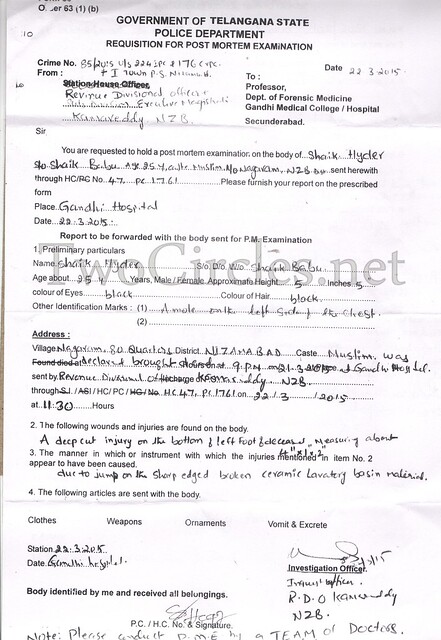

On 21 March 2015, Sheikh Hyder was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died on the same day in the police station in Telangana. The Police claimed that Sheikh Hyder died due to injuries inflicted while he was trying to escape from the police station, but the postmortem report states that injury marks on his back and feet indicate that he was brutally beaten. Hyder was declared dead on arrival by the hospital, where he was taken by his family, several hours after the Police released him.

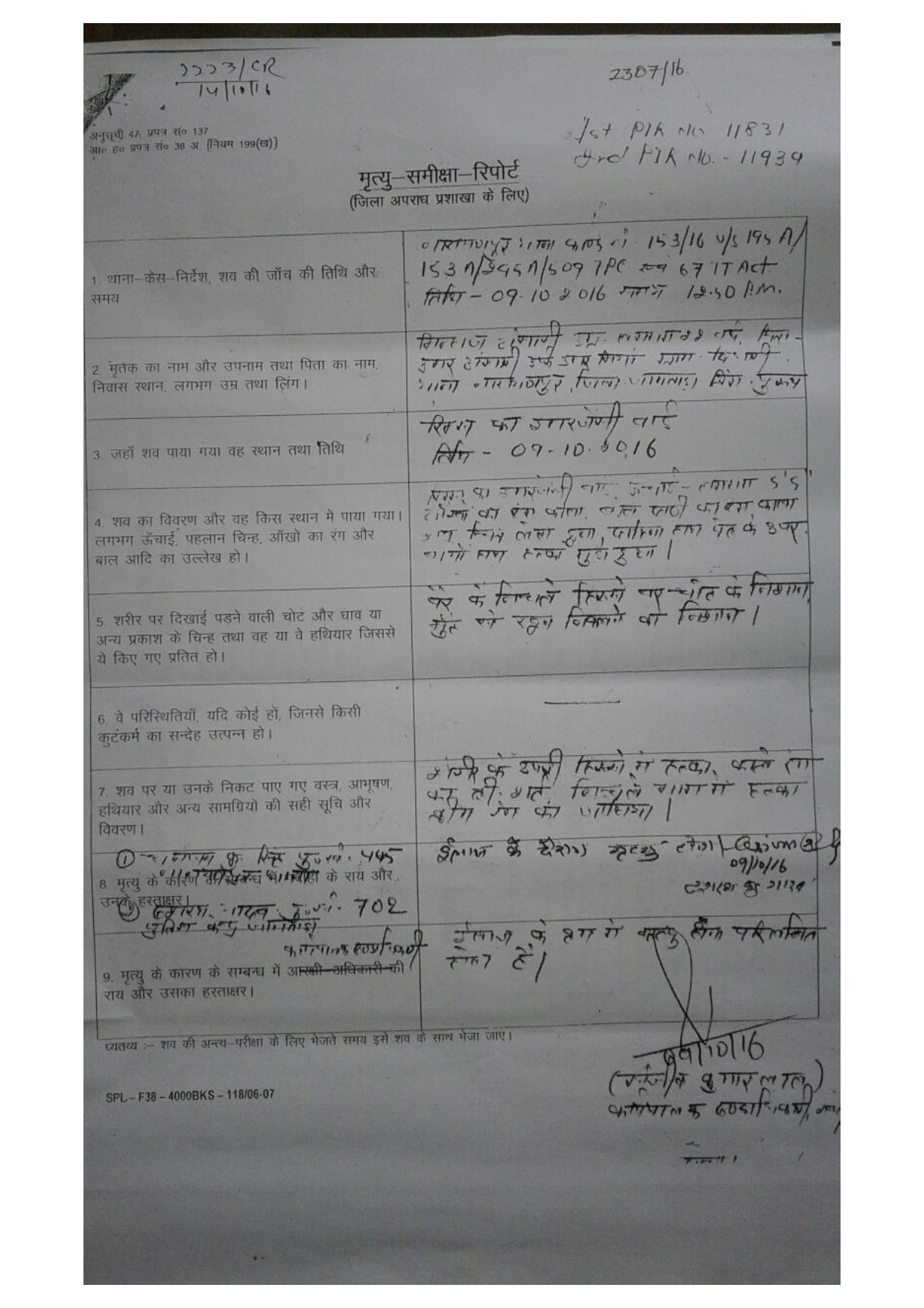

Copy of the first two pages of the response to Lateef Khan’s RTI on the postmortem report in Sheikh Hyder’s case. Source: TwoCircles.net

Viqaruddin Ahmed was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in Hyderabad in which two policemen died. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” in Telangana on 7 April 2015 while he was being escorted to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail by 17 policemen. Several rights activists claimed that there are several gaps in the Police’s version of Viqaruddin Ahmed’s death. Photos of the scene showed four people handcuffed and chained in the Police bus, while it was alleged that the five men were armed and had attempted to attack the Police. The victims had numerous bullet wounds, while none of the policemen were injured at all.

In G.Bonappa’s case the Police claim that he was inebriated during the Bonalu festival and was dancing with a procession in Hyderabad. They claim that they picked him up on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015. The Police claimed that they kept him in the station overnight and released him the next morning. They maintained that Bonappa consumed liquor and food after he was released from the police station and that he died of asphyxiation. The police station was attacked by 200 infuriated locals closely following Bonappa’s death and Rapid Action Force personnel were deployed outside the police station.

Padma was called in for questioning to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015, when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August. When N. Padma’s condition did not improve, she was shifted to the Acute Medical Care unit at 1:30 AM where she succumbed to her injuries at 6:15 AM on 23 August 2015. Sources said the injuries on her body were fresh and not older than six to eight hours. The Police said she had a history of medical problems and died of them in the hospital and they denied any allegations of torture by them.

Lakshman was an accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district, Telangana. Lakshman died on the way to the hospital when he was being taken there by the Police. A police officer said, “While T. Lakshman was in the sub inspector’s room in the police station, he removed his shirt and attempted to hang himself from window grills at around 4 AM”. According to the Police, a constable noticed Lakshman and had him moved to a nearby hospital from where he was referred to a government hospital in Hyderabad. However, he died on the way to the hospital on 12 March 2015.

Obaidur Rahman was wanted by the West Bengal police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015. The Police allege Rahman was initially admitted at Malda Medical College for treatment, and died on the way to Kolkata city, where he was referred for treatment. A complaint was lodged against sub inspector Bikash Haldar and two other police officers by Rahman’s daughter before the Malda Deputy Superintendent of Police. However, the Police refused to file a complaint against the police officials, and only filed a case of unnatural death. They denied the fact that they had taken Rahman into custody, saying that he fell sick in front of the police station and so they had taken him directly to the hospital.

Bhushan Deshmukh was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in Kolkata, West Bengal. Burtolla police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual.

There is limited information from news reports focusing solely on the police version of events in a few of the cases discussed above.

While analyzing data from official sources, it is important to remember that biases among police personnel exist and affect the way the Police interact with citizens. For the Status of Policing in India 2019 report 11,834 police personnel across the country were interviewed regarding police infrastructure and attitudes of the Police. An IndiaSpend analysis of the report reveals that one out of five police personnel feel that killing dangerous criminals is better than a legal trial. Three out of four personnel feel that it is justified for the Police to be violent towards criminals and four out of five personnel believe that there is nothing wrong with the Police beating up criminals to extract confessions. These attitudes are reflected in the cases where the Police deny any allegations of torture by them when clear evidence from postmortems provide contexts for brutality by the Police. Often, claims of police torture are not formally registered at police stations and thus custodial death cases are not reflected in the data collected in the NCRB reports.

The 2016 Human Rights Watch report on custodial deaths in India, finds that in addition to physically abusing suspects to gain information in investigations, police also beat and torture suspects as retribution, choosing to punish crimes themselves instead of doing the necessary and arduous work to gather evidence that will bring convictions in court. The report also finds instances where custodial deaths were intentionally misreported as suicides or fatalities due to illness or natural causes. In many of the cases that HRW tracked, the Police asserted that the victim had died of a heart attack a few hours after he was arrested or detained.

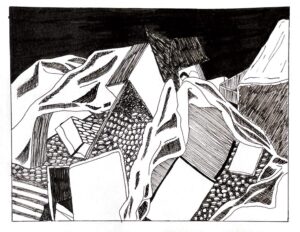

The serious and real nature of torture in Indian prisons needs to be highlighted to counter the flimsy excuses and reasons presented by the Police to justify deaths and escape accountability. In Innocent Prisoners, Abdul Wahid Shaikh lists some of the various forms of torture employed by the Indian law enforcement agencies. These include the flour mill belt – an often used tool to beat the prisoner and the 180-degree torture, where the Police makes the prisoner lie down and stretches the prisoner’s legs far apart that they are at 180 degrees. The Police then jump on the prisoner’s thighs to cause further pain. Other methods include stripping the prisoner naked before and after torture so that the prisoner loses any sense of self respect, causing electric shock to the prisoner’s private parts and torturing the anus by injecting substances. Waterboarding is another method where the prisoner is made to lie with their head at a lower elevation, the face is covered with a cloth and water is splashed on the face with a hose pipe to cause a sensation of drowning and suffocation. Other methods include burning body parts with cigarettes, plucking the prisoner’s hair, stripping the prisoner naked in freezing temperatures and sensory bombardment where the prisoner is tied up and music is played loudly close to his ears. Sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, being subjected to foul language and mock executions are other methods of torture highlighted by Shaikh.

Anthropologist Veena Das, in Slum Acts (2022), using the example of the 2006 Mumbai bomb blasts, stresses the need to question official narratives. While academic and legal scholarship on legal cases use the Police narrative as the focus of their analysis, it is important to note that the Police narrative forms only one of many narratives that exist in each case. In cases of custodial deaths where the stakes of proving the Police’s innocence are very high, legal orders, judgements, witnesses, documents and any evidence produced by the Police must be treated with the highest level of scrutiny. Das adds that the Courts and the Police produce not only evidence and people as witnesses but also narratives, which are just one in the set of narratives involved in a case of custodial death. This is also important given the fact that the Police has access to and is found tampering with records such as police diaries, arrest memos, and police logbooks which is another serious issue in custodial death cases.

From the Police version of events in the cases of custodial deaths, the vulnerability and easy culpability of young, marginalized men is evident. It is important to question the perception that since victims of custodial deaths are alleged to be criminals and thus deemed guilty without a trial, their deaths are justified as a result of their criminality. In the next essay in this series, we focus on the types of accountability, if any, that have taken place in these 15 cases.

Related Posts

“Akira Kurosawa’s classic ‘Roshomon’ is a reminder that there are several versions of the same story, each seeming right, depending on who is saying it, when it is said and from what standpoint.”

Dr. S. Muralidhar, Judge, High Court of Delhi, The Trajectories of Criminal Law.

In part two of this series, we focus on police narratives, or on the “official” version of events. We explore the excuses, reasons and causes of death according to the Police and other state bodies in all 15 cases. In this essay we discuss data on the types and frequencies of different official causes of death in police and judicial custody. We also highlight the various kinds of torture inflicted on persons in custody, and include studies on police biases against individuals from certain sections of society.

The Police in India often attribute deaths in police or judicial custody to “natural causes”. Viral infections, suicides, asphyxiation and other reasons are common causes of deaths, according to the Police. As mentioned in the first essay of this series, 22-year-old Altaf hung himself from the water pipeline using the string of the hood of his jacket according to the Police. Such bizarre and illogical reasoning is not uncommon when it comes to official custodial death narratives by the Indian police. In a scenario where the victim does not have the agency or the ability to voice the truth and their families are under pressure from the Police, the Police version of events becomes the official and often repeated narrative. However, postmortem reports and testimonies from family members provide evidence of widespread police brutality and torture. Cases of bribery and corruption to prevent the families from filing a formal complaint are common and so are threats to families who do file a complaint against the Police.

The National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) Crime in India (CII) reports use data reported from police stations across the country; these, however, may not always be transparent and accurate as discussed in the previous essay. The 2015 CII report provides the reasons for custodial deaths. Suicide was listed as the highest in 34 cases, followed by hospitalization in 12 and illness in 11. Natural deaths were listed in nine cases and in six it was injuries due to physical assault by the Police when the victim was in police custody. Death due to escaping from police custody was listed in five cases. Similarly, the 2016 CII report lists suicide as the major cause of custodial deaths in 38 cases, followed by illness in 15 (outside the hospital) and 13 (inside the hospital). Injuries sustained due to physical assault by the Police are listed as the reason for deaths in eight cases and natural deaths are listed as the reason in seven cases. Political scientist Jinee Lokaneeta, while highlighting the case of the death of Jishan, a Muslim man who died in February 2022 in Delhi’s Tihar Jail, discusses the use of “natural causes” as the official reason for death. Lokaneeta calls for an urgent re-examination of the category and mentions that even though there were visible external and internal injuries on Jishan’s body, his death was categorized as “due to natural causes.” The postmortem report in Jishan’s case did not draw any inferences from the mention of external injuries, which were clearly produced as an effect of physical assault and not by natural causes as the Police claimed.

On 3 October 2016, Minhaj Ansari and two of his friends were arrested from their village Dighari in Jamtara district, in the state of Jharkhand. After two days in police custody, he was finally taken to a hospital in Ranchi to be treated for injuries where he was eventually declared dead on 9 October 2016. In Ansari’s case, the Police initially said that the cause of death, as a provisional diagnosis, was likely to have been encephalitis, a viral infection. However, the postmortem report stated the presence of internal and external injuries caused by a hard and blunt object. The initial injury report dated 6 October 2016 confirmed this. According to court documents that we accessed for this case- specifically the case diary highlighting sections of the Criminal Investigation Department investigation – in the timeline of events, evidence and witnesses pointed to Ansari being arrested on 3 October 2016. However, the police station records showed his arrest on 4 October 2016 at 1:15 PM local time.

In a letter dated 26 September 2017, doctors at the Rajendra Institute of Medical Sciences (RIMS), Ranchi commented on the postmortem report. The letter noted that the external abrasions caused were grievous in nature and the external injuries are “not sufficient to cause death in the ordinary course of nature.” The cause of death is the combined effects of injuries and their complications in the form of congestions, hemorrhages and necrosis in the brain, kidney, liver and gastrointestinal tract. The autopsy report did not find any evidence of either encephalitis or any viral infection.

P. Ramkumar, from Tamil Nadu, was arrested by the Chennai Police on 2 July 2016. He was arrested in connection with an alleged murder on 24 June 2016. He died on 18 September 2016 in judicial custody in a high-security prison, a week before his judicial custody expired. He was brought dead to the Government Royapettah Hospital in Chennai, and the Police claimed that he had killed himself. They claimed that around 5 PM on 18 September, he was allowed out of the dispensary block where he was being held after he asked to drink some water, which was when he allegedly broke open a switchboard and bit into electrical wires, leading to his death by electrocution. Reports said that a constable who claimed to have opened the door to the dispensary block and two prisoners had given eyewitness statements. The statements claimed that Ramkumar was brought to the prison doctor in an unconscious state before being taken to the hospital, where he was declared dead. According to the Human Rights Advocacy and Research Foundation’s fact-finding report, the Police’s version of Ramkumar’s death by suicide in the high security Puzhal Central Prison in Chennai on 18 September 2016 was highly questionable.

On 19 September 2016, Ramkumar’s father, Paramasivam, filed an injunction requesting a doctor of the family’s choosing to conduct Ramkumar’s postmortem examination. The Court, however, rejected this plea stating that the postmortem could be conducted by an expert from the Delhi All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Delhi and aided by doctors at Royapettah Hospital. The postmortem report concluded that Ramkumar died due to electrocution and noted a dozen electrical burns. It did not point to any additional injuries.

Ramkumar’s family and medical experts have dismissed the findings of the postmortem as false. Sampath Kumar, the head of the forensics department at Saveetha University, who has been an expert investigator in many of Tamil Nadu’s most controversial cases, told journalist Sujatha Sivagnanam at The Caravan, that Ramkumar almost certainly did not die from electrocution. Kumar also added that the switchboard that Ramkumar allegedly broke open was more than six feet from the ground. To bite into the wires, Ramkumar would have had to yank the wires down with his hands, which would have led to other electrical injuries that are not noted in the postmortem report. Kumar had been nominated by Ramkumar’s father as expert witness during the postmortem, but the Court did not allow him to attend. It took four years of legal proceedings and protests by Dalit organizations for officials to finally share the postmortem report with Ramkumar’s family and legal counsel. The Tamil Nadu State Human Rights Commission (TNSHRC) took cognizance of the case five years later. In August 2021, the two histopathologists who had examined Ramkumar’s body immediately after the postmortem deposed before the TNSHRC. Their report contradicted the findings of the postmortem. According to them, none of the body tissue collected, including from Ramkumar’s lips and tongue, suggested any damage by electrocution.

Abdul Khader, the casualty medical officer at Royapettah Hospital who examined Ramkumar’s body, also deposed before the TNSHRC. During his cross examination, he made several claims that contradicted the police account. He said that there was no evidence suggesting that Ramkumar had been treated at the prison clinic. Moreover, rigor mortis had started setting into the body, which usually starts only twelve hours after death. He also told the TNSHRC that the injuries he saw were not electrical injuries. Shortly after Khader’s cross examination by the commission, R. Anbalagan, the jail superintendent at Puzhal, asked the Madras High Court to issue a stay order on the inquiry, which the Court granted. According to a report in The Caravan, R. Thomas, Anbalagan’s advocate, said that they had opposed the inquiry because the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) had already conducted a probe into the case. The three medical reports produced by the hospital Ramkumar was taken to indicate that he had a deep cut on the right side of his neck and a smaller one on the left side. The full report of the TNSHRC is still not publicly available.

Shameel Basha, 26, was picked up by the Pallikonda Police from Vellore on 15 June and detained in police custody till 18 June in connection with a missing person’s case of a former colleague. He died in Rajiv Gandhi Government General Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, on 26 June 2015 following health complications which he reportedly developed while in police custody. The NHRC noted that the inquest report revealed injuries on the victim included swelling on the right chest, blood clot on the left hip, blood clot on the left back, blood clot on the right shoulder band, injuries on the right-hand wrist and right-hand elbow. It also suggested that the injuries were caused due to a stick or lathi. The postmortem report revealed several abrasions and contusions on different parts of the body and the final cause of death, based upon the viscera and histopathology report, was due to complications of multiple blunt injuries. The magisterial inquiry report conducted by the Judicial Magistrate, Vellore, also concluded that the deceased appeared to have died of complication and multiple blunt injuries. The NHRC observed that the deceased had died due to custodial torture by the Police of the Pallikonda police station and was of the opinion that “the State is vicariously liable to compensate to the next of kin of the deceased.”

Meenkulambu Karthik was picked up by the Police for a robbery in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. He died on 21 September 2016, when he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. Hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. The Police, based on CCTV footage, established that Karthik was one of four people who were accused of snatching the chain of a female techie, two days before his death. Karthik was detained at the Kannagi Nagar police station for questioning and his family was told two days later that he was rushed to the hospital as he complained of breathlessness. The hospital authorities said that he was brought dead. Those who knew him alleged that Karthik was innocent and that his incarceration and death was a case of police brutality and murder.

After Karthik’s death, the family claimed that they were given a bribe by the Police from the Kannagi Nagar police station to refrain from pursuing a complaint on the issue. According to a September 2016 news report, Ganga, Karthik’s mother, said that the family was offered an amount of Rs. 400,000 by policemen at the Kannagi Nagar police station. Ganga alleged that an amount of Rs. 200,000 was given to the family as a bribe, and another Rs. 200,000 was offered to them. Ganga filed a complaint with the Police Commissioner regarding the custodial death of her son. She stated in her letter of complaint that when she saw her son’s body at the Rajiv Gandhi Government Hospital, it was covered with injuries including on his head and thighs. The complaint also stated that his right leg was broken.

In her complaint, Ganga said that on 19 September 2016, Karthik left the house saying that he was going to buy a sim card. The following day, some people living nearby told her that Karthik and his friend Arunachalam had been arrested. When she went to Kannagi Nagar station at around 1:30 PM, the Police told her that he was not there and had been taken to another station for investigation. They also told her that her son was lying to the Police and was not cooperating with them. On 21 September, she said that the Police had told her that during the robbery, her son had suffered some injuries and had been admitted to Rajiv Gandhi Government Hospital, and on that same night she found out that her son had died. On 22 September, she was finally allowed to see her son’s body at the hospital. Ganga stated that she then went back to the Kannagi Nagar police station on the same day to file a complaint in regard to his death, but the Police did not file a complaint. They also did not show her the FIR filed against Karthik and Arunachalam. In her complaint, Ganga has named two policemen – sub-inspector Bhagyaraj and head constable Vijaykumar – of the Kannagi Nagar police station and blamed them for Karthik’s death, possibly due to the injuries that she saw on his body and due to the bribe amount offered by the Police.

Kuppuswamy, a petty shop owner from Sanarpatti in Dindigul district, was arrested by the Police for allegedly selling liquor illegally. Subsequently, Kuppuswamy was remanded and lodged in Madurai prison in Tamil Nadu. While in custody, the Police had called his family members and informed them that Kuppuswamy had died due to illness. His family refused to buy the Police claim of natural death and staged a protest in front of Sanarpatti police station. They also condemned the Police for arresting him in a false case. During the protest, a family member said that policemen had brutally assaulted Kuppuswamy and that he sustained serious internal injuries and eventually succumbed to them. “Hence, the personnel involved in the abuse and attack of Kuppuswamy should be suspended and a proper investigation should be conducted into his death”, said Kuppuswamy’s family while also demanding monetary compensation. However, the Police have refuted the charges of custodial death. A senior police official claimed that Kuppuswamy was suffering from nausea and from a serious ailment. He was immediately rushed to Madurai Government Royapettah Hospital but died on the way. The Sanarpatti Police corroborated the view of the senior official and a source at Sanarpatti police station claimed that Kuppuswamy was weak and suffering from a serious ailment even during the time of arrest.

Mohan, a Sri Lankan national in his early forties, was picked up by the Police in Tamil Nadu. He died a few hours after he was picked up and taken for questioning on 3 September 2015. According to reports, Mohan was assaulted by the Pallikaranai police personnel during an inquiry and fainted in the station. By the time the Police took him to the Global Hospital in Perumbakkam, Chennai, he died. Mohan’s body was then shifted to the Government Royapettah Hospital for an autopsy. The Police, however, maintained that Mohan died of a cardio-pulmonary arrest. The Police managed to get it in writing from Mohan’s partner that he had died of a cardiac arrest. They also promised monetary compensation and a job for her eldest son.

Bujji, who was taken into police custody for his alleged role in the fatal stabbing of the Hosur Town police station head constable, died within a few hours of his capture, on 15 June 2016. While allegations arose that it was a case of custodial killing, the Police said the 19-year-old had died as a result of a cardiac arrest while in custody.

Gokulakannan, 22, was a contract laborer from Karumalaikoodal village in Tamil Nadu, who was picked up by the Police in connection with a murder. He was picked up around midnight and was rushed to the Mettur General Hospital in Salem, and later to the Government Mohan Kumaramangalam Medical College Hospital in Salem, where he was declared “brought dead.” He died on 6 June 2015. Local activists said that the Police threatened and bribed the family to take back their allegations of custodial torture.

On 21 March 2015, Sheikh Hyder was arrested for an alleged bicycle theft and died on the same day in the police station in Telangana. The Police claimed that Sheikh Hyder died due to injuries inflicted while he was trying to escape from the police station, but the postmortem report states that injury marks on his back and feet indicate that he was brutally beaten. Hyder was declared dead on arrival by the hospital, where he was taken by his family, several hours after the Police released him.

Copy of the first two pages of the response to Lateef Khan’s RTI on the postmortem report in Sheikh Hyder’s case. Source: TwoCircles.net

Viqaruddin Ahmed was a suspect in the Mecca Masjid bombing in Hyderabad in which two policemen died. The Police killed Ahmed and four others in an “encounter” in Telangana on 7 April 2015 while he was being escorted to the Hyderabad Court from Warangal Jail by 17 policemen. Several rights activists claimed that there are several gaps in the Police’s version of Viqaruddin Ahmed’s death. Photos of the scene showed four people handcuffed and chained in the Police bus, while it was alleged that the five men were armed and had attempted to attack the Police. The victims had numerous bullet wounds, while none of the policemen were injured at all.

In G.Bonappa’s case the Police claim that he was inebriated during the Bonalu festival and was dancing with a procession in Hyderabad. They claim that they picked him up on 2 August 2015 after he got into a fight with a home guard. He died the following day on 3 August 2015. The Police claimed that they kept him in the station overnight and released him the next morning. They maintained that Bonappa consumed liquor and food after he was released from the police station and that he died of asphyxiation. The police station was attacked by 200 infuriated locals closely following Bonappa’s death and Rapid Action Force personnel were deployed outside the police station.

Padma was called in for questioning to the Asifnagar police station in Hyderabad, Telangana, in connection with a theft case. She was called in for questioning on 21 August 2015, when she was sick, and called in again the next day on 22 August. When N. Padma’s condition did not improve, she was shifted to the Acute Medical Care unit at 1:30 AM where she succumbed to her injuries at 6:15 AM on 23 August 2015. Sources said the injuries on her body were fresh and not older than six to eight hours. The Police said she had a history of medical problems and died of them in the hospital and they denied any allegations of torture by them.

Lakshman was an accused in a murder case and was arrested by the Pulkal Police in Medak district, Telangana. Lakshman died on the way to the hospital when he was being taken there by the Police. A police officer said, “While T. Lakshman was in the sub inspector’s room in the police station, he removed his shirt and attempted to hang himself from window grills at around 4 AM”. According to the Police, a constable noticed Lakshman and had him moved to a nearby hospital from where he was referred to a government hospital in Hyderabad. However, he died on the way to the hospital on 12 March 2015.

Obaidur Rahman was wanted by the West Bengal police in a criminal case arising out of a land dispute with his neighbor. Rahman died in police custody in Malda within 24 hours of his arrest, on 21 January 2015. The Police allege Rahman was initially admitted at Malda Medical College for treatment, and died on the way to Kolkata city, where he was referred for treatment. A complaint was lodged against sub inspector Bikash Haldar and two other police officers by Rahman’s daughter before the Malda Deputy Superintendent of Police. However, the Police refused to file a complaint against the police officials, and only filed a case of unnatural death. They denied the fact that they had taken Rahman into custody, saying that he fell sick in front of the police station and so they had taken him directly to the hospital.

Bhushan Deshmukh was arrested under the Arms Act for possession of illegal weapons on 20 September 2015 in Kolkata, West Bengal. Burtolla police claimed he died of diarrhea, but a post-mortem report revealed multiple injuries all over the body, suggesting that he was beaten up by more than one individual.

There is limited information from news reports focusing solely on the police version of events in a few of the cases discussed above.

While analyzing data from official sources, it is important to remember that biases among police personnel exist and affect the way the Police interact with citizens. For the Status of Policing in India 2019 report 11,834 police personnel across the country were interviewed regarding police infrastructure and attitudes of the Police. An IndiaSpend analysis of the report reveals that one out of five police personnel feel that killing dangerous criminals is better than a legal trial. Three out of four personnel feel that it is justified for the Police to be violent towards criminals and four out of five personnel believe that there is nothing wrong with the Police beating up criminals to extract confessions. These attitudes are reflected in the cases where the Police deny any allegations of torture by them when clear evidence from postmortems provide contexts for brutality by the Police. Often, claims of police torture are not formally registered at police stations and thus custodial death cases are not reflected in the data collected in the NCRB reports.

The 2016 Human Rights Watch report on custodial deaths in India, finds that in addition to physically abusing suspects to gain information in investigations, police also beat and torture suspects as retribution, choosing to punish crimes themselves instead of doing the necessary and arduous work to gather evidence that will bring convictions in court. The report also finds instances where custodial deaths were intentionally misreported as suicides or fatalities due to illness or natural causes. In many of the cases that HRW tracked, the Police asserted that the victim had died of a heart attack a few hours after he was arrested or detained.

The serious and real nature of torture in Indian prisons needs to be highlighted to counter the flimsy excuses and reasons presented by the Police to justify deaths and escape accountability. In Innocent Prisoners, Abdul Wahid Shaikh lists some of the various forms of torture employed by the Indian law enforcement agencies. These include the flour mill belt – an often used tool to beat the prisoner and the 180-degree torture, where the Police makes the prisoner lie down and stretches the prisoner’s legs far apart that they are at 180 degrees. The Police then jump on the prisoner’s thighs to cause further pain. Other methods include stripping the prisoner naked before and after torture so that the prisoner loses any sense of self respect, causing electric shock to the prisoner’s private parts and torturing the anus by injecting substances. Waterboarding is another method where the prisoner is made to lie with their head at a lower elevation, the face is covered with a cloth and water is splashed on the face with a hose pipe to cause a sensation of drowning and suffocation. Other methods include burning body parts with cigarettes, plucking the prisoner’s hair, stripping the prisoner naked in freezing temperatures and sensory bombardment where the prisoner is tied up and music is played loudly close to his ears. Sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, being subjected to foul language and mock executions are other methods of torture highlighted by Shaikh.

Anthropologist Veena Das, in Slum Acts (2022), using the example of the 2006 Mumbai bomb blasts, stresses the need to question official narratives. While academic and legal scholarship on legal cases use the Police narrative as the focus of their analysis, it is important to note that the Police narrative forms only one of many narratives that exist in each case. In cases of custodial deaths where the stakes of proving the Police’s innocence are very high, legal orders, judgements, witnesses, documents and any evidence produced by the Police must be treated with the highest level of scrutiny. Das adds that the Courts and the Police produce not only evidence and people as witnesses but also narratives, which are just one in the set of narratives involved in a case of custodial death. This is also important given the fact that the Police has access to and is found tampering with records such as police diaries, arrest memos, and police logbooks which is another serious issue in custodial death cases.

From the Police version of events in the cases of custodial deaths, the vulnerability and easy culpability of young, marginalized men is evident. It is important to question the perception that since victims of custodial deaths are alleged to be criminals and thus deemed guilty without a trial, their deaths are justified as a result of their criminality. In the next essay in this series, we focus on the types of accountability, if any, that have taken place in these 15 cases.

SUPPORT US

We like bringing the stories that don’t get told to you. For that, we need your support. However small, we would appreciate it.